Again Revised CC Submission Mattson Revised Small City Gay Bars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Food Business Awards 2017

GLEN EIRA CITY COUNCIL JUNE 2017 VOLUME 227 gleneira news VOLUME 194 NEWS Food Business Awards 2017 Council recognises local Bistro 309 has been named Glen Eira City butter chicken and beef or lamb vindaloo, per year — this equates to about $100 per volunteersLocal volunteers honoured Council’s Shop of the Year. to ossobucco di vitello and pollo alla household per week. With less time being Open space — a high cacciatora.” spent on meal preparation in the home, Announced at Council’s annual Food priority consumers are putting more trust in local Recycling A to Z on Business Awards 2017 on Monday 1 May, Darwan said he feels very lucky and proud food businesses to provide food that is safe website the Bentleigh restaurant received the to have received Shop of the Year. to eat. award from Glen Eira Mayor Cr Mary Have your say on the “The hard work of my wife and our small Delahunty for achieving the highest food Council’s Five-Star Safe Food Program New2014–15 dads’ Draft playgroup Annual team of staff has made it possible for safety rating after being assessed by demonstrates our commitment to working Budget Bistro 309 to earn this award,” he said. Council’s environmental health officers in partnership with the local food industry during 2016. 2017 award finalists to ensure food is safe for consumers. This year, there were 10 finalists and Avoca Catering in Ormond was named To achieve a Five-Star food safety rating, each business was nominated as the best Shop of the Year Runner-up. -

New Age, Vol. 5 No.1, April 29, 1909

The New Age, Tuesday,April 29th, 1909 ENLARGED MAY-DAY NUMBER THE NEW AGE A WEEKLY REVIEW OF POLITICS, LITERATURE AND ART, No. 764] THURSDAY,APRIL 29, 1909 ONE PENNY CONTENTS. PAGE PAGE -NOTESOF THE WEEK ... ... ... ... ... I Whited SEPULCHRES--Chapter I. BeatriceBy Tina .... 13 IN DEFENCEOF AROBINDAGHOSH .... ... ... 3 A Clump OF RUSHES.By David Lowe ... ... ... 14 SOCIALISTPOLITICS ... ... ... ... ... 4 REVIEWS: Russia’s New Era ... 15 THE INSOLENTHEATHEN ... ... ... 5 DRAMA : “Those Damned Little Clerks” By Cecil AN ETHICALMARRIAGE SERVICE‘” ... ... ... 5 Chesterton ... ... ... ... ... ... 16 AN ENGLISHMAN’SBACK GARDEN. By Edgar Jepson ... 6 MUSIC : Castorand Pollux. ByHerbert Hughes ... ... 19 JOAN OF ARCAND BRITISHOPINION. By Joseph Clayton ... CORRESPONDENCE: Paul Campbell, H. Russell Smart, A SHRIEKOF WARNING-11. By G. K. Chesterton ... 7 Arnold Bennett, Henry C. Devine, Edward Agate, R. W. SYMPATHYAND UNDERSTANDING.By Eden Phillpotts ... 10 Talbot Cox,. Cicely Hamilton, C. H. Norman, F. L. BOOKSAND PERSONS. By Jacob Tonson ... ... I2 Billington-Grieg ... ... ... ... ... 20 ALL BUSINESS COMMUNICATIONS should be ad- escapedthem, we can only saythat had he endured dressed to the ‘Manager, 12-14Red Lion Court Fleet St., London. them,he would notnow be where he is.. Thereare ADVERTISEMENTS : The latesttime for receiving Ad- only twothings necessary in modernelementary edu- vertisments is first post Monday for the same week’s issue. cation : to abolish the schoolsand to abolish the SUBSCRIPTION RATES for England and Abroad: teachers. Of thethree factors, the children are the Three months .. IS. 9d. sole uncorrupted. Six months . .. 3s. 3d. ** * Twelve months ... 6s. 6d. All remittances should be made payable to THENEW AGE PRESS, ‘Lord Crewe, the Colonial Secretary, had the audacity LTD.,and sent to 12-14,Red Lion Court, Fleet Street, London todeclare in the House of Lordson Wednesday that The Editorial address is 4, Verulam Buildings Gray’s Inn, he had never seen any difficulty in defending the system W.C. -

View Entire Issue As

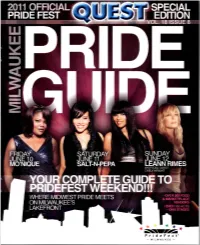

Some things we all have in common. There's nobody like State Farm® to protect the things we all value. Like a good neighbor, State Farm is therep CALL AN AGENT 08 VISIT uS ONLINE TODAY. SfateRarm statefarm.com. 1101024 Slate Farm . Home 0ifico . Bloomington, lL Special Deals IN you buy your ticket at our main gates? Hold on to it and take advantage Of the generous offer from HOURS: Get the VIP experience at PrideFe§t! Ppotawatomi Bingo Casino printed on the back Of the Friday, June loth,3PM . Mldnlght From -day to 3rday UItimate VIP, ticket. \fou can redeem your Gckct at any Frfekeep- Saturday, Juno llth,12PM . Midnigl.t PrideFest has a special experience for you: us Club Booth (FKC) at Potawatomi Bingo Casino Sunday, Juno 12th,12PM -10PM (grounds), and 1-Day VIP . $100 for $10 in FKC Reward Play (After 10 slot points earned in your same day visit) lt's valid June 10- 12Midnighl (PUMPI Dance Pav!llon) 3-Day VIP - $225 VIP Ultimate w/ Meat & Greet se50i500 Sseptember 30. to be eligible, you must be at least Ll years oid, and be a member Of the FKC. Mem- Purchasi ng Tickets depending on artist. t PndeFest patons have the opporfunftyto experience a bbeship is free! \falld only at Potawatomi Bingo (1-Day VIP also available at gate during weekend) number of benefits: lntemat]onal entertalnment, educa- Ccasino,1721 W. Canal Street, MihAraukee Wisoon- swh. View fuH details on the tieket stub. Good luck! tion and advocacy, music and dancing, fun family and These VI P tickets help support the festival's mis- ¢ ##,aA#ife#de:chca°Pnp;nagnafd|n#g#e¥#a# sion and operations while letting you experience PrideFest in style! 1-Day VIP includes admission for advantage of sons Of PndeFests special promotons: the day, and 3.Day gives you admission for the en- ae wwoavshoan tire weekend. -

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes Associate Professor Department of American Culture, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures & Department of Women’s Studies Director, Latina/o Studies Program University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ADDRESS American Culture, 3700 Haven Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (734) 647-0913 (office) (734) 936-1967 (fax) [email protected] http://larrylafountain.com EDUCATION Columbia University Ph.D. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1999. Dissertation: Culture, Representation, and the Puerto Rican Queer Diaspora. Advisor: Jean Franco. M.Phil. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1996. M.A. Spanish & Portuguese, May 1992. Master’s Thesis: Representación de la mujer incaica en Los comentarios reales del Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Advisor: Flor María Rodríguez Arenas. Harvard College A.B. cum laude in Hispanic Studies, June 1991. Senior Honors Thesis: Revolución y utopía en La noche oscura del niño Avilés de Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá. Advisor: Roberto Castillo Sandoval. Universidade de São Paulo Undergraduate courses in Brazilian Literature, June 1988 – Dec. 1989. AREAS OF INTEREST Puerto Rican, Hispanic Caribbean, and U.S. Latina/o Studies. Queer of Color Studies. Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Transnational and Women of Color Feminism. Theater, Performance, and Cultural Studies. Comparative Ethnic Studies. Migration Studies. XXth and XXIth Century Latin American Literature, including Brazil. PUBLICATIONS (ACADEMIC) Books 2009 Queer Ricans: Cultures and Sexualities in the Diaspora. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. xxvii + 242 pages. La Fountain-Stokes CV October 2013 Page 1 La Fountain-Stokes CV October 2013 2 Reviews - Enmanuel Martínez in CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 24.1 (Fall 2012): 201-04. -

January 16,1880

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. IS ADVANCE. FRIDAY MORNING, JANUARY 16, 1S80. TERMS 88.00 PEB ANNUM, ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862.-TOL A PORTLAND, tlie Maine Democrat was ever so tender and THE BUYERS’ GUIDE. MISCELLANEOUS. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, THE PRESS. sensitive on the of fraud. WANTS._ _MISCELLANEOUS. _ | subject Published every dry (Sundays excepted) by the FRIDAY JANUARY l«. Tiie sin attributed to Noah’s accursed son, Wanted. TRADE CIRCULAR. Swallowing MORNING, PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO., that of the nakedness of his kin, is 4 N to travel for a Flour and exposing Portland. experience salesman, At 109 Exchange St., ix Grocery house. Route, Shore Towns and Every regular attach^ of the Press is furnished greatly affected by the Greenbackers. We Aroostook. None but those having a trade need ap- Terms : Dollars a Year. To mail subscrib- STOCK with a Card certiilcate signed by Stanley T. Pullen, have had the of a man Eight WE HAVE spectacle charging Me. TAKEN in advance. ply. Address P. O. Box 1258, Portland, ers Seven Dollars a Year, if paid RETAIL TRADE All steamboat and hole jal4 lw* POISON. Editor. railway, managers his cousin with bribery, and of a father ac- will confer a favor upon us by demanding credentials THE MAINE-OTATE PRESS CATARRH IS THE MOST PREVALENT cusing his son. Now we see a man soiling Wanted. of every person claiming to represent our journal. TnunsDA v Morning at $2.50 a and find broken lots of OF of known disease. It is insidious and his brother’s name. s published every BURNISHED Parlor and communicating room, many PORTLAND, ME., any gen- if in advance at §2.00 a year. -

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes Associate Professor Department of American Culture, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures Department of Women’s Studies, Latina/o Studies Program University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ADDRESS American Culture, 3700 Haven Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (734) 647-0913 (office) (734) 936-1967 (fax) [email protected] http://larrylafountain.com https://umich.academia.edu/LarryLaFountain EDUCATION Columbia University Ph.D. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1999. Dissertation: Culture, Representation, and the Puerto Rican Queer Diaspora. Advisor: Jean Franco. M.Phil. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1996. M.A. Spanish & Portuguese, May 1992. Master’s Thesis: Representación de la mujer incaica en Los comentarios reales del Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Advisor: Flor María Rodríguez Arenas. Harvard College A.B. cum laude in Hispanic Studies, June 1991. Senior Honors Thesis: Revolución y utopía en La noche oscura del niño Avilés de Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá. Advisor: Roberto Castillo Sandoval. Universidade de São Paulo Undergraduate courses in Brazilian Literature, June 1988 – Dec. 1989. AREAS OF INTEREST Puerto Rican, Hispanic Caribbean, and U.S. Latina/o Studies. Queer of Color Studies. Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Transnational and Women of Color Feminism. Theater, Performance, and Cultural Studies. Comparative Ethnic Studies. Migration Studies. XXth and XXIth Century Latin American Literature, including Brazil. PUBLICATIONS (ACADEMIC) Books 2009 Queer Ricans: Cultures and Sexualities in the Diaspora. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. xxvii + 242 pages. La Fountain-Stokes CV February 2017 Page 1 La Fountain-Stokes CV February 2017 2 Reviews - Enmanuel Martínez in CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 24.1 (Fall 2012): 201-04. -

Win Prizes from Erie Gay News

October 2011 Erie Pride Parade & Rally recap pg 16 October 2003 Erie Pride weekend pages 9-12 EGNErie Gay News Erie GLBT Contingent in Edinboro Homecoming Parade Oct 8 by Michael Mahler Erie’s GLBT Community has been invited to participate in Edinboro University’s annual homecom- ing parade on October 8, which draws thousands of spectators. The 2011 theme is Jungle Safari because GRRRREAT Things Happen Here! The parade will take place through the town and campus this year. Pa- rade line-up is scheduled for 9 AM at the intersection of Heather and Darrow on the Edinboro University cam- pus with the parade beginning at 11 AM. The thousands of Edinboro University alumni, faculty, staff, students and area residents who are present along the parade route look forward to our involvement. This is a great way to promote local GLBT visibility by participating in this cherished tradition at Edinboro University. You can RSVP at the Facebook page for Erie Gay News under Events. (It is helpful to RSVP, but not required!) The Dr. Who contingent, getting ready to step off at the Erie Diversity Worship service on Oct 23 Pride Parade & Rally August 27. Photo by Deb Spilko at Community United Church Community United Church, 1011 W 38th St, We will also list the event on the Erie Gay News site. Erie PA, will again hold a Diversity Service on Sunday, Erie Gay News is one of the sponsors of the event. October 23, at 11:00 AM. In this annual celebration, we highlight what it means for a Christian community to be open and affirming, welcoming people of all “Respectful Relationships sexual orientations, gender identities, racial/ethnic backgrounds, ability levels, ages, and so forth. -

Mipcom 2018 New Programming Passion Distribution

MIPCOM 2018 • MIPCOM 2018 NEW PROGRAMMING NEW PROGRAMMING PASSION DISTRIBUTION PASSION PART OF THE TINOPOLIS GROUP Passion Distribution Ltd. No.1 Smiths Square 77-85 Fulham Palace Road London W6 8JA T. +44 (0)207 981 9801 E. [email protected] www.passiondistribution.com WELCOME Welcome to MIPCOM 2018 It is my absolute pleasure to share with you our latest slate of programmes and formats. As always, Passion Distribution brings to market a rich and diverse selection of engaging factual entertainment series, compelling documentaries and must-watch entertainment shows that fulfil your programming needs. Headlining our Factual Entertainment slate, shows such as Emma Willis: Delivering Babies, The Sex Testers and Dr Christian: 12 Hours To Cure Your Street are testament to the continuing interest from audiences in Health and Wellbeing content. Also produced by Firecracker Films, Postcode Playdates is a revealing, insightful and feel good format that will conquer hearts. WELCOME Thought-provoking documentaries continue to feature prominently in our content mix. The fascinating Cruel Cut and The Trouble With Women do not shy away from tackling cultural issues and extraordinary human stories. Machinery Of War explores technological advancements and innovations of combat, satisfying both engineering and history enthusiasts. Access driven documentaries are always in high demand, so we are delighted to have partnered with BBC Studios to offer you an unprecedented glimpse of diplomatic going-ons with Inside the Foreign Office at a turbulent and eventful time amid tensions with Russia, Trump presidency and Brexit negotiations! Finally, as we celebrate our 10th anniversary this year, it is comforting to see that outstanding entertainment shows continue to defy the test of time. -

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes

Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes Associate Professor Dept. of American Culture, Romance Languages and Literatures, and Women’s Studies College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor ADDRESS American Culture, 3700 Haven Hall Ann Arbor, MI (USA) 48109 1 (734) 647-0913 (office) 1 (734) 936-1967 (fax) [email protected] http://larrylafountain.com https://umich.academia.edu/LarryLaFountain EDUCATION Columbia University Ph.D. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1999. New York, NY, USA Dissertation: Culture, Representation, and the Puerto Rican Queer Diaspora. Advisor: Jean Franco. M.Phil. Spanish & Portuguese, Feb. 1996. M.A. Spanish & Portuguese, May 1992. Master’s Thesis: Representación de la mujer incaica en Los comentarios reales del Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Advisor: Flor María Rodríguez Arenas. Harvard College A.B. cum laude in Hispanic Studies, June 1991. Cambridge, MA, USA Senior Honors Thesis: Revolución y utopía en La noche oscura del niño Avilés de Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá. Advisor: Roberto Castillo Sandoval. Universidade de São Paulo Undergraduate courses in Brazilian Literature, June 1988 – Dec. 1989. São Paulo, SP, Brazil AREAS OF INTEREST Puerto Rican, Hispanic Caribbean, and Latinx Studies. Queer of Color Studies. Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Cultural Studies. Theater and Performance Studies. Transnational and Women of Color Feminism. Comparative Ethnic Studies. Migration Studies. XXth and XXIth Century Latin American Literature, including Brazil. PUBLICATIONS (ACADEMIC) Books (Single-Authored) 2018 Escenas transcaribeñas: ensayos sobre teatro, performance y cultura. San Juan: Isla Negra Editores, 2018. 296 pages. Reviews La Fountain-Stokes CV JULY 2019 Page 1 La Fountain-Stokes CV JULY 2019 2 - Lissette Rolón Collazo in Revista Iberoamericana 85.225 (2019): 281-283. -

Media Approved

Film and Video Labelling Body Media Approved Video Titles Title Rating Source Ti me Date F o r m a t Applicant Point of Sales Approved Director Cuts "Is Born" Series Box Set,The (8 DVD Set) PG Contains low level offensive language FVLB 1,125.00 21/08/2007 DVD The Warehouse Peter Walker No cut noted Slick Yes 21/08/2007 100 Favourite Action Songs and Rhymes G FVLB 36.00 01/08/2007 DVD The Warehouse Neil Ben No cut noted Slick Yes 01/08/2007 100 Favourite Fairy Tales and Stories G FVLB 41.00 01/08/2007 DVD The Warehouse Not Stated No cut noted Slick Yes 01/08/2007 100 Favourite Sing-A-Long Songs and Rhymes G FVLB 38.00 01/08/2007 DVD The Warehouse Neil Ben No cut noted Slick Yes 01/08/2007 100 Years of Triumph G FVLB 47.00 01/08/2007 DVD Th e Warehouse Not Stated No cut noted Slick Yes 01/08/2007 1000 Words R18 Contains explicit sex scenes FVLB 75.37 28/08/2007 DVD DVD Wholesale Limited David Stanley No cut noted Slick Yes 28/08/2007 101 Lesbian Beauties (Disc 1) R18 Contains explicit sex scenes OFLC 118.26 08/08/2007 DVD Metro Interactive Australasia Not Stated No cut noted Slick Yes 08/08/2007 101 Lesbian Beauties (Disc 2) R18 Contains explicit sex scenes OFLC 117.46 08/08/2007 DVD Metro Interactive Australasia Not Stated No cut noted 1421 - The Year China Discovered the World G LBVP 114.00 15/08/2007 DVD Southbound Distribution Ltd David Wallace No cut noted Slick Yes 15/08/2007 20th Century Symphonic Sounds G FVLB 71.00 10/08/2007 DVD The Warehouse Not stated No cut noted Slick Yes 10/08/2007 25th Hour/He Got Game R16 Contains offensive -

The Book 1 TG-Ato Z Intro 30/5/05 15:04 Page 1

1 TG-Ato Z cover 30/5/05 10:22 Page 3 INTERNATIONAL Personal Reports Personal Profiles Listings Shops Services Events Places to Go Edited by Vicky Lee The Book 1 TG-Ato Z intro 30/5/05 15:04 Page 1 CONTENTS Front cover Photograph: 1 INDEX Introduction Valmir Silva 2 Introducing This new book Transgender AtoZ Cover Model: 6 Introducing links between books and websites 8 Introducing links between publishing and club Alekssandra Ceiliato 10 Introducing TG words, concepts & definitions 14 Introducing WayOut Personal Profiles 16 Personal Profile of the editor - Vicky Lee 21 Super Report A year with Tranny Grange - Nicki 28 Super Report Working Girls - Monica Dream girl 36 Super Report Brazillian Girls - Alekssandra Ceciliato 40 INDEX International Section Listing PLUS 41 Euro Events 2005/2006 68 Personal Profile of Jaquline from Germany 43 Personal Profile Sasha De Monaco from Holland 50 Australia Report - Christie McNichol 55 Belgium Report - Pamela 59 Denmark Report - Rebecca Holm 65 Finland Report - Mandy Romero 70 Germany Report - Charis Berger 81 Holland Report - Monica Dreamgirl 90 Gran Canaria Report - The Gemini Club 92 Ibiza Report - Cathy Kissmet 96 Thailand’s Alcazar Report - Nikki 99 INDEX USA Section Listing PLUS Book Editor: Vicky Lee 98 USA Events 2005/2006 DTP: Vicky Lee and Karen 101 Event Report SCC Atlanta - Vicky Lee Research & editing: Karen 106 Event Report Dignity Cruises - Peggy & Melanie Advertising sales: 110 Personal Profile of Michelle Zee 112 Personal Profile of Fionnola Orlando Sue Mills at Planet Advertising 160