Last-Glacial-Cycle Glacier Erosion Potential in the Alps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characteristics of the Bergschrund of an Avalanche-Cone Glacier in the Canadian Rocky Mountains

JOlIl"lla/ o/G/aci%gl'. VoL 29. No. 10 1. 1983 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BERGSCHRUND OF AN AVALANCHE-CONE GLACIER IN THE CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS By G ERALD OSBORN (Department of Geology and Geophysics, Uni versity o f Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N I N4, Canada) ABSTRACT. Fi eld study of th e bergschrund of a small avalanche-cone glacier at the base of Mt Chephren, in Banff Nati onal Park , has been ca rried out as part of a general ex pl oratory study of glacier-head crevasses in th e Canadi an Roc ki es. The bergsc hrun d consists of a wide. shall ow. partl y bedrock-fl oored gap, und erneath whi ch ex tends a nearl y vertical Ralldklu!I, and a small , offset, subsidi ary crevasse (or crevasses). The fo ll owin g observations rega rdin g the behavior of th e bergsc hruncl and ice adjacent to it are of parti cul ar interest: ( I) topograph y of the subglaeial bedrock is a control on the location of the main bergschrund and subsidi a ry crevasses. (2) th e main bergschrund and subsid ia ry crevasse(s) are conn ected by subglacial gaps betwee n bedrock and ice; th e gaps are part of th e "bergschrund system" , (3) snow/ ice immedi ately down-glacier of the bergschrund system moves nea rl y verticall y dow nwa rd in response to rotational fl ow of the glacier. a ll owin g the bergschrund components to keep the same location and size fro m year to year, (4) an inde pend ent accumul ati on, fl ow. -

Jökulhlaups in Skaftá: a Study of a Jökul- Hlaup from the Western Skaftá Cauldron in the Vatnajökull Ice Cap, Iceland

Jökulhlaups in Skaftá: A study of a jökul- hlaup from the Western Skaftá cauldron in the Vatnajökull ice cap, Iceland Bergur Einarsson, Veðurstofu Íslands Skýrsla VÍ 2009-006 Jökulhlaups in Skaftá: A study of jökul- hlaup from the Western Skaftá cauldron in the Vatnajökull ice cap, Iceland Bergur Einarsson Skýrsla Veðurstofa Íslands +354 522 60 00 VÍ 2009-006 Bústaðavegur 9 +354 522 60 06 ISSN 1670-8261 150 Reykjavík [email protected] Abstract Fast-rising jökulhlaups from the geothermal subglacial lakes below the Skaftá caul- drons in Vatnajökull emerge in the Skaftá river approximately every year with 45 jökulhlaups recorded since 1955. The accumulated volume of flood water was used to estimate the average rate of water accumulation in the subglacial lakes during the last decade as 6 Gl (6·106 m3) per month for the lake below the western cauldron and 9 Gl per month for the eastern caul- dron. Data on water accumulation and lake water composition in the western cauldron were used to estimate the power of the underlying geothermal area as ∼550 MW. For a jökulhlaup from the Western Skaftá cauldron in September 2006, the low- ering of the ice cover overlying the subglacial lake, the discharge in Skaftá and the temperature of the flood water close to the glacier margin were measured. The dis- charge from the subglacial lake during the jökulhlaup was calculated using a hypso- metric curve for the subglacial lake, estimated from the form of the surface cauldron after jökulhlaups. The maximum outflow from the lake during the jökulhlaup is esti- mated as 123 m3 s−1 while the maximum discharge of jökulhlaup water at the glacier terminus is estimated as 97 m3 s−1. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Korean Direct

AAC Publications Korean Direct The First Ascent Of Gasherbrum V Insignificant against the blinding white backdrop of Gasherbrum V’s south face, we stood like silhouettes atop a moraine, the wall before us in full view. The complex glacier leading up to the face reminded me of scaly dragon’s tail. We had spotted a snaking line that would lead us to the jagged bergschrund at the foot of the wall. Once on the face, we would have to keep left to avoid a menacing serac, then move right in the upper mixed section before finishing with a direct line to the top. Seong Nak-jong and I had never really considered a route on the south side of unclimbed Gasherbrum V until we were denied passage up the northeast face. We had started our first attempt on the 7,147- meter peak from Camp 1 on the South Gasherbrum Glacier, along the normal routes to Gasherbrums I and II. We trudged through thigh-deep snow to reach the northeast face, which was covered in loose ice and snow, and was nearly impossible to protect. Falling ice and spindrift poured down from above. We finally had no choice but to evacuate from our high point of 6,400 meters. This unsuccessful attempt quashed our desire to climb. As the leader of our small team, the quandaries of a second attempt weighed heavily on my mind. Not only were we physically weakened and our confidence shot, it was already mid-July and more snow was laying siege to the camps. We had been away from home for more than a month. -

Analysis of Groundwater Flow Beneath Ice Sheets

SE0100146 Technical Report TR-01-06 Analysis of groundwater flow beneath ice sheets Boulton G S, Zatsepin S, Maillot B University of Edinburgh Department of Geology and Geophysics March 2001 Svensk Karnbranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 32/ 23 PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK Analysis of groundwater flow beneath ice sheets Boulton G S, Zatsepin S, Maillot B University of Edinburgh Department of Geology and Geophysics March 2001 This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. Summary The large-scale pattern of subglacial groundwater flow beneath European ice sheets was analysed in a previous report /Boulton and others, 1999/. It was based on a two- dimensional flowline model. In this report, the analysis is extended to three dimensions by exploring the interactions between groundwater and tunnel flow. A theory is develop- ed which suggests that the large-scale geometry of the hydraulic system beneath an ice sheet is a coupled, self-organising system. In this system the pressure distribution along tunnels is a function of discharge derived from basal meltwater delivered to tunnels by groundwater flow, and the pressure along tunnels itself sets the base pressure which determines the geometry of catchments and flow towards the tunnel. -

Ice-Stream Flow Switching by Up-Ice Propagation of Instabilities Along Glacial Marginal Troughs

Ice-stream flow switching by up-ice propagation of instabilities along glacial marginal troughs Etienne Brouard1* & Patrick Lajeunesse1 5 1 Centre d’études nordiques & Département de géographie, Université Laval, Québec, Québec Correspondence to: Etienne Brouard ([email protected]) Abstract. Ice stream networks constitute the arteries of ice sheets through which large volumes of glacial ice are rapidly delivered from the continent to the ocean. Modifications in ice stream networks have a major impact on ice sheets mass balance and global sea level. Reorganizations in the drainage network of ice streams have been reported in both modern and palaeo- 10 ice sheets and usually result in ice streams switching their trajectory and/or shutting down. While some hypotheses for the reorganization of ice streams have been proposed, the mechanisms that control the switching of ice streams remain poorly understood and documented. Here, we interpret a flow switch in an ice stream system that occurred prior to the last glaciation on the northeastern Baffin Island shelf (Arctic Canada) through glacial erosion of a marginal trough, i.e., deep parallel-to-coast bedrock moats located up-ice of a cross-shelf trough. Shelf geomorphology imaged by high-resolution swath bathymetry and 15 seismostratigraphic data in the area indicate the extension of ice streams from Scott and Hecla & Griper troughs towards the interior of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Up-ice propagation of ice streams through a marginal trough is interpreted to have led to the piracy of the neighboring ice catchment that in turn induced an adjacent ice stream flow switch and shutdown. -

Glacier Mass Balance Bulletin No. 11 (2008–2009)

GLACIER MASS BALANCE BULLETIN Bulletin No. 11 (2008–2009) A contribution to the Global Terrestrial Network for Glaciers (GTN-G) as part of the Global Terrestrial/Climate Observing System (GTOS/GCOS), the Division of Early Warning and Assessment and the Global Environment Outlook as part of the United Nations Environment Programme (DEWA and GEO, UNEP) and the International Hydrological Programme (IHP, UNESCO) Compiled by the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) ICSU (WDS) – IUGG (IACS) – UNEP – UNESCO – WMO 2011 GLACIER MASS BALANCE BULLETIN Bulletin No. 11 (2008–2009) A contribution to the Global Terrestrial Network for Glaciers (GTN-G) as part of the Global Terrestrial/Climate Observing System (GTOS/GCOS), the Division of Early Warning and Assessment and the Global Environment Outlook as part of the United Nations Environment Programme (DEWA and GEO, UNEP) and the International Hydrological Programme (IHP, UNESCO) Compiled by the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) Edited by Michael Zemp, Samuel U. Nussbaumer, Isabelle Gärtner-Roer, Martin Hoelzle, Frank Paul, Wilfried Haeberli World Glacier Monitoring Service Department of Geography University of Zurich Switzerland ICSU (WDS) – IUGG (IACS) – UNEP – UNESCO – WMO 2011 Imprint World Glacier Monitoring Service c/o Department of Geography University of Zurich Winterthurerstrasse 190 CH-8057 Zurich Switzerland http://www.wgms.ch [email protected] Editorial Board Michael Zemp Department of Geography, University of Zurich Samuel U. Nussbaumer Department of Geography, University of Zurich -

The Ministry for the Future / Kim Stanley Robinson

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental. Copyright © 2020 Kim Stanley Robinson Cover design by Lauren Panepinto Cover images by Trevillion and Shutterstock Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc. Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Orbit Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10104 www.orbitbooks.net First Edition: October 2020 Simultaneously published in Great Britain by Orbit Orbit is an imprint of Hachette Book Group. The Orbit name and logo are trademarks of Little, Brown Book Group Limited. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Robinson, Kim Stanley, author. Title: The ministry for the future / Kim Stanley Robinson. Description: First edition. -

1 Andrews Glacier in August 2016 Tyndall Glacier Lidar Scan in May

Final Report for “Glacier and perennial snowfield mass balance of Rocky Mountain National Park (ROMO): Past, Present, and Future” Task Agreement Number P16AC00826 PI Dr. Daniel McGrath June 28, 2019 Department of Geosciences Colorado State University [email protected] Andrews Glacier in August 2016 Tyndall Glacier LiDAR scan in May 2016 1 Summary of Key Project Outcomes • Over the past ~50 years, geodetic glacier mass balances for four glaciers along the Front Range have been highly variable; for example, Tyndall Glacier thickened slightly, while Arapaho Glacier thinned by >20 m. These glaciers are closely located in space (~30 km) and hence the regional climate forcing is comparable. This variability points to the important role of local topographic/climatological controls (such as wind-blown snow redistribution and topographic shading) on the mass balance of these very small glaciers (~0.1-0.2 km2). • Since 2001, glacier area (for 11 glaciers on the Front Range) has varied ± 40%, with changes most commonly driven by interannual variability in seasonal snow. However, between 2001 and 2017, the glaciers exhibited limited net change in area. Previous work (Hoffman et al., 2007) found that glacier area had started to decline starting in ~2000. • Seasonal mass turnover is very high for Andrews and Tyndall glaciers. On average, the glaciers gain and lose ~9 m of elevation each year. Such extraordinary amounts of snow accumulation is primarily the result of wind-blown snow redistribution into these basins (and to a certain degree, avalanching at Tyndall Glacier) and exceeds observed peak snow water equivalent at a nearby SNOTEL station by 5.5 times. -

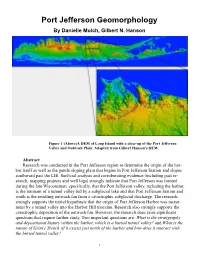

Port Jefferson Geomorphology by Danielle Mulch, Gilbert N

Port Jefferson Geomorphology By Danielle Mulch, Gilbert N. Hanson Figure 1 (Above)A DEM of Long Island with a close-up of the Port Jefferson Valley and Outwash Plain. Adapted from Gilbert Hanson's DEM. Abstract Research was conducted in the Port Jefferson region to determine the origin of the har- bor itself as well as the gentle sloping plain that begins in Port Jefferson Station and slopes southward past the LIE. Surficial analysis and corroborating evidence (including past re- search, mapping projects and well logs) strongly indicate that Port Jefferson was formed during the late Wisconsinan, specifically, that the Port Jefferson valley, including the harbor, is the remnant of a tunnel valley fed by a subglacial lake and that Port Jefferson Station and south is the resulting outwash fan from a catastrophic subglacial discharge. The research strongly supports the initial hypothesis that the origin of Port Jefferson Harbor was incise- ment by a tunnel valley into the Harbor Hill moraine. Research also strongly supports the catastrophic deposition of the outwash fan. However, the research does raise significant questions that require further study. Two important questions are: What is the stratigraphy and depositional history within the harbor, which is a buried tunnel valley? and What is the nature of Grim's Trench (if it exists) just north of the harbor and how does it interact with the buried tunnel valley? 1 Introduction In this paper, we propose that Port Jefferson valley is a tunnel valley created during the Wisconsinan. This valley cuts the Harbor Hill moraine. We also propose that the fan shaped feature immediately south of the valley is in fact a related alluvial fan that was deposited catastrophically when the sediment-rich water left the tunnel valley and lost energy abruptly. -

1953 the Mountaineers, Inc

fllie M®��1f�l]�r;r;m Published by Seattle, Washington..., 'December15, 1953 THE MOUNTAINEERS, INC. ITS OBJECT To explore and study the mountains, forests, and water cours es of the Northwest; to gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; to preserve by encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise, the natural beauty of North west America; to make expeditions into these regions in ful fillment of the above purposes ; to encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of out-door life. THE MOUNTAINEER LIBRARY The Club's library is one of the largest mountaineering col lections in the country. Books, periodicals, and pamphlets from many parts of the world are assembled for the interested reader. Mountaineering and skiing make up the largest part of the col lection, but travel, photography, nature study, and other allied subjects are well represented. After the period 1915 to 1926 in which The Mountaineers received books from the Bureau of Associate Mountaineering Clubs of North America, the Board of Trustees has continuously appropriated money for the main tenance and expansion of the library. The map collection is a valued source of information not only for planning trips and climbs, but for studying problems in other areas. NOTICE TO AUTHORS AND COMMUNICATORS Manuscripts offered for publication should be accurately typed on one side only of good, white, bond paper 81f2xll inches in size. Drawings or photographs that are intended for use as illustrations should be kept separate from the manuscript, not inserted in it, but should be transmitted at the same time. -

Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska

U. S. Department of the Interior BLM-Alaska Technical Report to Bureau of Land Management BLM/AK/TR-84/1 O December' 1984 reprinted October.·2001 Alaska State Office 222 West 7th Avenue, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska Herman W. Gabriel and Stephen S. Talbot The Authors HERMAN w. GABRIEL is an ecologist with the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office in Anchorage, Alaskao He holds a B.S. degree from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and a Ph.D from the University of Montanao From 1956 to 1961 he was a forest inventory specialist with the USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Regiono In 1966-67 he served as an inventory expert with UN-FAO in Ecuador. Dra Gabriel moved to Alaska in 1971 where his interest in the description and classification of vegetation has continued. STEPHEN Sa TALBOT was, when work began on this glossary, an ecologist with the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office. He holds a B.A. degree from Bates College, an M.Ao from the University of Massachusetts, and a Ph.D from the University of Alberta. His experience with northern vegetation includes three years as a research scientist with the Canadian Forestry Service in the Northwest Territories before moving to Alaska in 1978 as a botanist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. or. Talbot is now a general biologist with the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service, Refuge Division, Anchorage, where he is conducting baseline studies of the vegetation of national wildlife refuges. ' . Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska Herman W.