PARTY VOTING in COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: the UNITED STATES, TAIWAN, and JAPAN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ELECTION of 1912 Library of Congress of Library

Bill of Rights Constitutional Rights in Action Foundation SPRING 2016 Volume 31 No 3 THE ELECTION OF 1912 Library of Congress of Library The four candidates in the 1912 election, from L to R: William H. Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, Eugene V. Debs, and Woodrow Wilson. The 1912 presidential election was a race between four leaders Not surprisingly, the 1912 presidential election be- who each found it necessary to distinguish their own brand of came a contest over progressive principles. Theodore progressive reform. The election and its outcome had far reach- Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson, and ing social, economic, and political consequences for the nation. Eugene Debs campaigned to convince the electorate Rapid industrialization in the 19th century led to a that their vision for change would lead America into a variety of American economic and social problems. new age of progress and prosperity. Among them were child labor; urban poverty; bribery and political corruption; unsafe factories and indus- Roosevelt, Taft, and the Republican Party tries; and jobs with low wages and long hours. Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) committed him- Beginning as a social movement, progressivism self early in life to public service and progressive re- was an ideology (set of beliefs) aimed at addressing in- forms. After attending Harvard University and a year at dustrialism’s problems. It focused on protecting the Columbia Law School, Roosevelt was elected to the people from excessive power of private corporations. New York State Assembly. He subsequently served in a Progressives emphasized a strong role for government number of official posts, including the United States Civil to remedy social and economic ills by exposing cor- Service Commission, president of the board of New York ruption and regulating big business. -

Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa's Dominant

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 © Copyright by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System by Safia Abukar Farole Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Kathleen Bawn, Chair In countries ruled by a single party for a long period of time, how does political opposition to the ruling party grow? In this dissertation, I study the growth in support for the Democratic Alliance (DA) party, which is the largest opposition party in South Africa. South Africa is a case of democratic dominant party rule, a party system in which fair but uncompetitive elections are held. I argue that opposition party growth in dominant party systems is explained by the strategies that opposition parties adopt in local government and the factors that shape political competition in local politics. I argue that opposition parties can use time spent in local government to expand beyond their base by delivering services effectively and outperforming the ruling party. I also argue that performance in subnational political office helps opposition parties build a reputation for good governance, which is appealing to ruling party ii. supporters who are looking for an alternative. Finally, I argue that opposition parties use candidate nominations for local elections as a means to appeal to constituents that are vital to the ruling party’s coalition. -

The Current the Friendliest Club in Georgetown DECEMBER 2018

The Current The Friendliest Club in Georgetown DECEMBER 2018 Calendar of Events 1 LGA Awards Brunch 2 Diners Club Dinner 5 Gingerbread House Party 7 Berryville Christmas Party 8 MGA Breakfast Welcomes 8 Tennis Mixed Up Christmas Mixer DecemberNew Members 9 11 BCCCWA Holiday Dinner ALL DAY 13 BCCCMA Luncheon Spirits of Texas Tuesdays Wine & Whiskey 15 Breakfast with Santa Wednesdays Margarita & Mexican Martini 25 Merry Christmas! Thursdays Fired Up Fridays 29-30 Golf Junior Camp Satisfied Saturdays 31-4 Tennis Junior Camp Dec 7 December 15 6-9pm Breakfast with Santa Gingerbread House Party Golf December Golf Events Pro’s Corner 1 LGA Awards Brunch December 7th—Quit Putt-Zin Around Putting Clinic – 4pm to 5pm 7 Golf Shop Sale Pro Shop Sale- 6 pm to 9pm ( Pro Shop Will Be Closed from MGA Breakfast 8 4pm- 6pm to prepare) Jr. Golf Camp Looking for those last minute gifts? Maybe for yourself? 29-30 There will be a Keg of Beer in the shop to make your shopping experience a better one!!!! Golf Associations Reminder- December 31st all credit books get closed out so come check what you have in the pot and spend it. Tues 8:30 Sr. MGA Wed 8:30 LGA and 9 Holers, Junior Golf Camp Wed 12:30 MGA December 29th and 30th- 10am- 12pm Thurs All Day Golf Guest Day $25per junior Fri 1pm Skins/Quota Coming Soon January 1st Heaven and Hell 2 Person Battle 11am Shotgun SIGN UP IN THE $30 per member $40 for guests (Includes Lunch and Prizes) ACCOUNTING OFFICEInfo Front 9 is a Scramble - Pins in Center of the Greens and Heavenly Men White Tees and Ladies Red Tees -

Growing Democracy in Japan: the Parliamentary Cabinet System Since 1868

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge Asian Studies Race, Ethnicity, and Post-Colonial Studies 5-15-2014 Growing Democracy in Japan: The Parliamentary Cabinet System since 1868 Brian Woodall Georgia Institute of Technology Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Woodall, Brian, "Growing Democracy in Japan: The Parliamentary Cabinet System since 1868" (2014). Asian Studies. 4. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_asian_studies/4 Growing Democracy in Japan Growing Democracy in Japan The Parliamentary Cabinet System since 1868 Brian Woodall Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results. Copyright © 2014 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Woodall, Brian. -

The Decline of Collective Responsibility in American Politics

MORRIS P. FIORINA The Decline of Collective Responsibility inAmerican Politics the founding fathers a Though believed in the necessity of establishing gen to one uinely national government, they took great pains design that could not to lightly do things its citizens; what government might do for its citizens was to be limited to the functions of what we know now as the "watchman state." Thus the Founders composed the constitutional litany familiar to every schoolchild: a they created federal system, they distributed and blended powers within and across the federal levels, and they encouraged the occupants of the various posi tions to check and balance each other by structuring incentives so that one of to ficeholder's ambitions would be likely conflict with others'. The resulting system of institutional arrangements predictably hampers efforts to undertake initiatives and favors maintenance of the status major quo. Given the historical record faced by the Founders, their emphasis on con we a straining government is understandable. But face later historical record, one two that shows hundred years of increasing demands for government to act positively. Moreover, developments unforeseen by the Founders increasingly raise the likelihood that the uncoordinated actions of individuals and groups will inflict serious on the nation as a whole. The of the damage by-products industri not on on al and technological revolutions impose physical risks only us, but future as well. Resource and international cartels raise the generations shortages spectre of economic ruin. And the simple proliferation of special interests with their intense, particularistic demands threatens to render us politically in capable of taking actions that might either advance the state of society or pre vent foreseeable deteriorations in that state. -

Voting for Parties Or for Candidates: Do Electoral Institutions Make a Di↵Erence?

Voting for Parties or for Candidates: Do Electoral Institutions Make a Di↵erence? Elena Llaudet⇤ Harvard University September 14, 2014 Abstract In this paper, I analyze the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) data to put the U.S. case in a comparative context and explore the impact of electoral institutions on voting behavior. I find that the U.S. is not unique when it comes to party defection, defined as voting for a party other than ones own. Furthermore, when focusing on countries with mixed electoral systems, I find that electoral institutions have a substantial e↵ect on the degree to which the vote choice is party or candidate- centered, and thus, they might, in turn, have an impact on the level of incumbency advantage in the elections. ⇤Ph.D. from the Department of Government at Harvard University and current post-doctoral fellow in the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School ([email protected]). Elections in the U.S. have long been considered unique, with its candidate-centered pol- itics and high levels of incumbency advantage. In this paper, I aim to put the U.S. case in a comparative context and explore the e↵ect that electoral institutions have on the voting behavior of the electorate. In particular, I study whether electoral systems a↵ect the likeli- hood of party defection in lower house elections, a phenomenon defined as voting for a party other than one’s own. In addition, to the extent possible, I try to distinguish whether voters are casting a ballot for a di↵erent party for strategic purposes – voting for a party that has higher chances of winning than their preferred one – or to support a particular candidate due to the candidate’s personal attributes, such as incumbency status. -

The Liberal Democratic Party: Still the Most Powerful Party in Japan

The Liberal Democratic Party: Still the Most Powerful Party in Japan Ronald J. Hrebenar and Akira Nakamura The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was the national-level ruling party of Japan throughout the entire First Party System (1955–1993). Among the politi- cal systems of non-Socialist developed nations, Japan is unique in that except for a short period after World War II, when a Socialist-centered coalition gov- ernment ruled Japan in 1947–1948, conservative forces have continuously held power on the national level. In 1955, when two conservative parties merged to form the LDP, conservative rule was concentrated within that single organiza- tion and maintained its reign as the governing party for thirty-eight years. It lost its majority in the weak House of Councillors (HC) in the 1989 elections and then lost its control of the crucial House of Representatives (HR) in 1993. However, it returned to the cabinet in January 1996 and gained a majority of HR seats in September 1997. Since the fall of 1997, the LDP has returned to its long-term position as the sole ruling party on the Japanese national level of politics. However shaky the LDP’s current hold, its record is certainly un- precedented among the ruling democratic parties in the world. All of its com- petition for the “years in power” record have fallen by the sidelines over the decades. The Socialist Party of Sweden and the Christian Democratic Party of Italy have both fallen on hard times in recent years, and whereas the Socialists have managed to regain power in Sweden in a coalition, the CDP of Italy has self-destructed while the leftists have run Italy since 1996. -

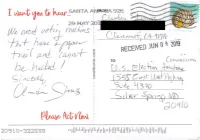

VVSG Comments

Before the U.S. ELECTION ASSISTANCE COMMISSION In the Matter of ) COMMENTS SUBMISSION ) VOLUNTARY VOTING SYSTEM ) Pursuant to 84 FR 6775, Doc. No.: 2019-03453 ) GUIDELINES VERSION 2.0 ) Wednesday, May 29th, 2019 ) DEVELOPMENT ) EAC Offices, Silver Spring, MD PUBLIC COMMENTS SUBMISSION OSET INSTITUTE COMMENTS LED BY GLOBAL DIRECTOR OF TECHNOLOGY EDWARD P. PEREZ REGARDING THE VOLUNTARY VOTING SYSTEM GUIDELINES VERSION 2.0 PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES Comment #1 Issue: Principles and Guidelines vs. Functional Requirements Reference: Overall VVSG 2.0 Structure The OSET Institute applauds the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (hereinafter, “EAC”) for making efforts to ensure that the future Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG) certification program is more flexible and agile than it has been in the past. With increasingly faster advances of technology matched by newly emerging cyber-security threats, it is essential for the VVSG to support regular adaptation and modification. Toward that end, VVSG 2.0's initial distinction between "Principles and Guidelines" versus "Functional Requirements" is well placed and laudable. In order to deliver on the promise of such a distinction, the OSET Institute believes that the following programmatic requirements must be adhered to: • “Principles and Guidelines" reflect policy statements, and any modifications to the Principles and Guidelines should require approval of EAC Commissioners. • Functional Requirements (and VSTL test assertions) do not represent policy statements, and their modification should not require approval of EAC Commissioners. Functional Requirements are simply the technical means to operationalize or implement the achievement of policy goals represented in the Principles and Guidelines. • Functional Requirements must support the policy goals represented in the Principles and Guidelines. -

Democratization and Electoral Reform

Comparative Political Studies Volume XX Number X Month XX X-X © Sage Publications Democratization and 10.1177/0010414006299097 http://cps.sagepub.com hosted at Electoral Reform in the http://online.sagepub.com Asia-Pacific Region Is There an “Asian Model” of Democracy? Benjamin Reilly Australian National University During the past two decades, numerous Asia-Pacific states have made the transition to democracy founded on basic political liberties and freely con- tested elections. A little-noticed consequence of this process has been strik- ingly congruent reforms to key political institutions such as electoral systems, political parties, and parliaments. The author argues that, across the region, these reforms have been motivated by common aims of promoting govern- ment stability, reducing political fragmentation, and limiting the potential for new entrants to the party system. As a result, similar strategies of institutional design are evident in the increasing prevalence of “mixed-member majoritar- ian” electoral systems, new political party laws favoring the development of aggregative party systems, and constraints on the enfranchisement of regional or ethnic minorities. Comparing the outcomes of these reforms with those of other world regions, the author argues that there has been an increasing con- vergence on an identifiable “Asian model” of electoral democracy. Keywords: democracy; electoral systems; political parties; Asia-Pacific he closing decades of the 20th century were years of unprecedented Tpolitical reform in the Asia-Pacific region. Major transitions from authoritarian rule to democracy began with the popular uprising against the Marcos regime in the Philippines in 1986 and the negotiated transitions from military-backed, single-party governments in Korea and Taiwan in 1987, moving on to the resumption of civilian government in Thailand in 1992, the UN intervention in Cambodia in 1993, the fall of Indonesia’s Suharto regime in 1998, and the international rehabilitation of East Timor that culminated in 2001. -

Varieties of American Popular Nationalism.” American Sociological Review 81(5):949-980

Bonikowski, Bart, and Paul DiMaggio. 2016. “Varieties of American Popular Nationalism.” American Sociological Review 81(5):949-980. Publisher’s version: http://asr.sagepub.com/content/81/5/949 Varieties of American Popular Nationalism Bart Bonikowski Harvard University Paul DiMaggio New York University Abstract Despite the relevance of nationalism for politics and intergroup relations, sociologists have devoted surprisingly little attention to the phenomenon in the United States, and historians and political psychologists who do study the United States have limited their focus to specific forms of nationalist sentiment: ethnocultural or civic nationalism, patriotism, or national pride. This article innovates, first, by examining an unusually broad set of measures (from the 2004 GSS) tapping national identification, ethnocultural and civic criteria for national membership, domain- specific national pride, and invidious comparisons to other nations, thus providing a fuller depiction of Americans’ national self-understanding. Second, we use latent class analysis to explore heterogeneity, partitioning the sample into classes characterized by distinctive patterns of attitudes. Conventional distinctions between ethnocultural and civic nationalism describe just about half of the U.S. population and do not account for the unexpectedly low levels of national pride found among respondents who hold restrictive definitions of American nationhood. A subset of primarily younger and well-educated Americans lacks any strong form of patriotic sentiment; a larger class, primarily older and less well educated, embraces every form of nationalist sentiment. Controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and partisan identification, these classes vary significantly in attitudes toward ethnic minorities, immigration, and national sovereignty. Finally, using comparable data from 1996 and 2012, we find structural continuity and distributional change in national sentiments over a period marked by terrorist attacks, war, economic crisis, and political contention. -

The New Trend in Japanese Domestic Politics and Its Implications

The New Trend in Japanese Domestic Politics and Its Implications Hiroki Takeuchi Southern Methodist University [email protected] ABSTRACT Japan has long been the most important ally of the United States in East Asia and it is widely viewed in Washington as a pillar of stability in the Asia-Pacific region. For a long time, the relationship with the United States, especially attitudes toward the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, determined the division between “right” and “left” in Japanese politics. However, this division has become meaningless during the last two decades since the Cold War ended, and a new division has emerged in Japanese politics over the attitudes toward domestic economic reforms and state- market relations. On the one hand, “conservatives” (hoshu-ha) try to protect the vested interests (kitoku keneki) that were created during the dominant rule by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). On the other hand, “reformists” (kaikaku-ha) try to advance economic reforms that would severely undermine those vested interests. This paper discusses the implications of this new trend in Japanese politics. Paper prepared for the Ostrom Workshop, Indiana University April 18, 2016 The paper is work in progress in the fullest sense. Please do not quote without the author’s permission. Comments and criticisms are welcome. 1 Japan has long been the most important ally of the United States in East Asia and it is widely viewed in Washington as a pillar of stability in the Asia-Pacific region. After World War II was over, Japan immediately became a U.S. partner in preserving the postwar international economic and political system. -

FAULT LINES Ridgites: Sidewalks Are City’S Newest Cash Cow by Jotham Sederstrom the Past Two Months; 30 Since the Beginning of the Brooklyn Papers the Year

I N S BROOKLYN’S ONLY COMPLETE U W L • ‘Bollywood’ comes to BAM O P N • Reviewer gives Park Slope’s new Red Cafe the green light Nightlife Guide • Brooklyn’s essential gift guide CHOOSE FROM 40 VENUES — MORE THAN 140 EVENTS! 2003 NATIONAL AWARD WINNER Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published weekly by Brooklyn Paper Publications at 26 Court St., Brooklyn, NY 11242 Phone 718-834-9350 © Brooklyn Paper Publications • 14 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol.26, No. 49 BRZ • December 8, 2003 • FREE FAULT LINES Ridgites: Sidewalks are city’s newest cash cow By Jotham Sederstrom the past two months; 30 since the beginning of The Brooklyn Papers the year. If you didn’t know better, you’d think “To me, it seems like an extortion plot,” said that some of the homeowners along a par- Tom Healy, who lives on the block with his ticular stretch of 88th Street were a little wife, Antoinette. Healy received a notice of vio- strange. lation on Oct. 24. / Ramin Talaie “It’s like if I walked up to your house and For one, they don’t walk the sidewalks so said, ‘Hey, you got a crack, and if you don’t fix much as inspect them, as if each concrete slab between Third Avenue and Ridge Boulevard it were gonna do it ourselves, and we’re gonna bring our men over and charge you.’ If it was were a television screen broadcasting a particu- Associated Press larly puzzling rerun of “Unsolved Mysteries.” sent by anyone other than the city, it would’ve But the mystery they’re trying to solve isn’t been extortion,” he said.