New Views from Library Drag Storytimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

Article Under Her Eye: Digital Drag As Obfuscation and Countersurveillance

Under Her Eye: Digital Drag as Obfuscation Article and Countersurveillance Harris Kornstein New York University, USA [email protected] Abstract Among drag queens, it is common to post screenshots comically highlighting moments in which Facebook incorrectly tags their photos as one another, suggesting that drag makeup offers a unique method for confusing facial recognition algorithms. Drawing on queer, trans, and new media theories, this article considers the ways in which drag serves as a form of informational obfuscation, by adding “noise” in the form of over-the-top makeup and social media profiles that feature semi-fictional names, histories, and personal information. Further, by performing identities that are highly visible, are constantly changing, and engage complex forms of authenticity through modes of camp and realness, drag queens disrupt many common understandings about the users and uses of popular technologies, assumptions of the integrity of data, and even approaches to ensuring privacy. In this way, drag offers both a culturally specific framework for conceptualizing queer and trans responses to surveillance and a potential toolkit for avoiding, thwarting, or mitigating digital observation. Introduction When particular surveillance technologies, in their development and design, leave out some subjects and communities for optimum usage, this leaves open the possibility of reproducing existing inequalities… [But] could there be some potential in going about unknown or unremarkable, and perhaps unbothered, where CCTV, camera-enabled devices, facial recognition, and other computer vision technologies are in use? —Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015: 162–63) Around late 2014, I began to take note of a curious social media phenomenon: drag queens were posting screenshots to Facebook to highlight instances in which the platform’s predictive facial recognition algorithms incorrectly tagged their photos as one another. -

2017 Grant CYCLE

A YEAR IN REVIEW Technical Assistance Grant Management System (GMS) Overview of Panelists Overview of Applicants Grants Budget Overview of Grantees Funding Recommendations TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE • Intro to GMS • 20 Minute Hands-On Computer Sessions • 15 Minute One-On-One Phone Calls • 15 Minute in person • Category Specific Workshops TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE cont’d Applicants who used technical assistance: Organizations Individuals • One-on-one: 17% • One-on-one: 21% • Workshops: 31% • Workshops: 18% • GMS Orientation: 14% • GMS Orientation: 12% Grantees who used technical assistance: Organizations Individuals • One-on-one: 20% • One-on-one: 21% • Workshops: 32% • Workshops: 25% • GMS Orientation: 14% • GMS Orientation: 8% GRANTS MANAGEMENT SYSTEM • 9 applications built • 30 users tested • 1 category due weekly • Various limitations OVERVIEW OF THE PANELISTS* 54 panelists total *As of April 26, 2017, 38 had responded to survey (70%) • 55% women; 3% non-binary • 8% have a disability • 29% identify as LGBQ • 79% are practicing artists • 16% practice a folk or traditional art • 63% are arts administrators, consultants, or run non- profits • 37% are educators or academics • 74% are first-time panelists • 39% have applied for an SFAC grant, 92% have been granted PANELIST OVERVIEW cont’d* 18-24 3% Age Artistic Discipline >60 2% Literary Visual 18% 29% 25-44 Media 45-60 50% 16% 45% Theater 14% Architec Race Music Dance -ture 9% 9% 2% Other Black 3% White 18% 29% Multiple 13% Native Arab/ American Middle 3% Eastern Asian 3% 26% Latino 8% *38 panelists -

June 2019 Stonewall at 50: a Major Anniversary Offers Opportunity For

June 2019 Stonewall at 50: A Major Anniversary Offers Opportunity for New Historical Perspectives by Lexi Adsit Stonewall: For the LGBTQ community, this one word conjures up a range of emotions and beliefs. This month marks the 50th anniversary of the 1969 riots at the eponymous New York City bar, often mistakenly described as the birthplace of the modern LGBTQ movement. As we celebrate this symbolic episode, it's worth remembering that the riots are a complex and contested event, one whose legacy remains a subject of debate. For fresh perspectives on this iconic event, History Happens interviewed Marc Stein, vice chair of the GLBT Historical Society Board of Directors. A professor of history at San Francisco State University, Stein is the author of the new book The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History (NYU Press, 2019). His research places Stonewall in a broader national context that positions the riots not as a starting point, but as a turning point. How were the Stonewall Riots viewed in California? News didn’t travel as quickly then as it does now, but many people found out via telephone conversations, friendship networks and word- of-mouth. Mainstream media didn’t provide much coverage, but alternative newspapers such as the Berkeley Barb and Berkeley Tribe and LGBTQ periodicals such as The Ladder in San Francisco and The Advocate in Los Angeles did better. Their reports suggest that many Californians viewed the Stonewall rebellion through the prism of recent developments on the West Coast. For everyone who knew about the anti-gay police killings of Howard Efland in Los Angeles (March 1969), Frank Bartley in Berkeley (April 1969), and Philip Caplan in Oakland (June 1969), the police raid on the Stonewall seemed like yet another instance of violent state repression. -

Feminist Press Catalog

FEMINIST PRESS CATALOG FALL 2019–SPRING 2020 CONTENTS 2 Fall 2019 Titles CONTACT INFORMATION 8 Spring 2020 Titles EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & PUBLISHER Jamia Wilson [email protected] 14 Amethyst Editions SENIOR EDITOR & FOREIGN RIGHTS MANAGER Lauren Rosemary Hook [email protected] 16 Backlist Highlights SENIOR SALES, MARKETING & PUBLICITY MANAGER Jisu Kim [email protected] 25 Rights & Permissions FIEBRE TROPICAL TABITHA AND MAGOO DRESS UP TOO A Novel Michelle Tea Juliana Delgado Lopera lllustrated by Ellis van der Does Uprooted from Bogotá into an ant-infested “Whether you know it or not, you are waiting for a book like this. Fiebre Tropical is a triumph, and we’re all triumphant in its presence.” —DANIEL HANDLER Miami townhouse, fifteen-year-old Francisca is miserable in her strange new city. Her alienation grows when her mother is swept up into an evangelical church replete with abstinent salsa dancers and baptisms for the dead. But there, Francisca meets the magnetic Carmen: head of the youth group and the FIEBRE pastor’s daughter. As her mother’s mental TROPICAL health deteriorates, Francisca falls for Car- men and turns to Jesus to grow closer with her, even as their relationship hurtles toward a shattering conclusion. JULIANA DELGADO LOPERA is an award-winning A NOVEL BY JULIANA DELGADO LOPERA Colombian writer and historian based in San Francisco. “ Fiebre Tropical is a triumph, and we’re all AMETHYST EDITIONS is a modern, queer imprint Tabitha and Magoo love to play dress up in MICHELLE TEA is the author of the novel triumphant in its presence.” founded by Michelle Tea. -

Booksinc.Net for the Absolute Latest Event Information!

Visit www.booksinc.net for the absolute latest event information! In this newsletter Book Clubs · Page 7 Biographies · Page 6 ENDORSE Events · Pages 4-5 Fiction · Page 2 Kids Books · Page 8 Nonfi ction · Page 3 NYMBC TM · Page 7 PRIDE Trade Paper · Page 6 JUNE CAN’T The experience you download “Every generation of Americans has brought our Nation closer to fulfi lling its promise of equality. While progress Cecil Castellucci Angus Whyte Sarah Dessen Alvin Orloff Christopher Moore Mike Adamick Andrea Carla Michaels Andrea Carla Michaels Larry-Bob Roberts joSon has taken time, our achievements in advancing the rights of Jan-Philipp Sendker Bernadette Luckett Maureen Langan Thea Hillman Jami Attenberg LGBT Americans remind us that history is on our side, and Gloria Steine Maureen Langan Corina Vacco Daphne Gottlieb Ramsey Hootman that the American people will never stop striving toward lib- Letty Pogrebin Cindy Caponera Stephanie Keuhn Michelle Tea Lisa Brackmann erty and justice for all.” — Barack Obama Robert K. Lewis Sue Kolinsky Seth Lerer Stephanie Rosenbaum Daryl Wood Gerber Helen E. Fisher Monica Wesolowska Ransom Riggs Daniel Smith Kate Carlisle Abigail Tarttelin Julian Guthrie David Margolick Jen Sincero Juliet Blackwell June 5 · 7:30 PM Linda Joy Myers Susan Schorn Eli Brown Cathleen Peck David Mezzapelle An editor of the UK’s Phoenix magazine, Abigail Tarttelin shares Judith Newton John Rocco Jo Robinson Mark Abramson Tara Ison Karen Joy Fowler Christopher Wolf Daniel LeVesque Michael Levi Kristen McCloy Golden Boy, a riveting coming-of-age story of a family in crisis as Temple Grandin Marissa Moss Justin Chin Carl Hiaasen Ellen Plotkin Mullholland their façade as an effortlessly excellent unit crumbles around them when their biggest secret is revealed. -

News Censorship Dateline

NEWS CENSORSHIP DATELINE LIBRARIES In his October video, Dorr reads To fight back against the self- Coeur D’Alene, Idaho a blog post titled “May God and the anointed censor, the library is display- Books that a patron judged to be crit- Homosexuals of OC Pride Please For- ing the recently found missing movies ical of President Donald Trump disap- give Us!” from his website, which he with a sign that reads: “The Berkley peared from the shelves of the Coeur calls “Rescue The Perishing.” The Public Library is against censorship. d’Alene Public Library. video ends with Dorr burning Two Someone didn’t want you to check Librarian Bette Ammon fished this Boys Kissing, a young adult novel by these items out. They deliberately hid complaint from the suggestion box: David Levithan; Morris Micklewhite all of these items so you wouldn’t find “I noticed a large volume of books and the Tangerine Dress, a children’s them. This is not how libraries work.” attacking our president. And I am book about a boy who likes to wear a Arnsman said the most recent Fifty going to continue hiding these books tangerine dress, by Christine Balda- Shades movie, Fifty Shades Freed, was in the most obscure places I can find cchino; This Day In June, a picture noticed missing in mid-June. A year to keep this propaganda out of the book about a pride parade, by Gayle ago, she said, the second of three Fifty hands of young minds. Your liberal E. Pitman, and Families, Families, Fam- Shades movies, Fifty Shades Darker, angst gives me great pleasure.” ilies! by Suzanne and Max Lang, about also went mysteriously missing. -

LGBTQIA Pride Month Program Guide 2018

PRIDE LGBTQIA Join San Francisco Public Library’s 2018 PRIDE Programs this June! Adults life lived amidst widespread violence and represents SATURDAY JUNE 2, 2:00-4:00 PM Black gay men’s collective, political longings for futures *Film: The Danish Girl - Danish painter Einar Wegener beyond the forces of anti-blackness and anti-queerness. begins living as a woman named Lili Elbe and undergoes one of the world's first gender-reassignment surgeries in Dr. Bost is Assistant Professor of Sexuality Studies and the 1930s. Lili struggles with her new identity as it strains Assistant Director of the Center for Research and her marriage to artist Gerda Wegener. Education on Gender and Sexuality, San Francisco State Chinatown University, and author of Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence, TUESDAY JUNE 5, 4:00-8:00 PM 2019, University of Chicago Press. Sponsored by the Pride Kick-off: Drag Queen Movie Fest - In To Wong Foo, African American Center of San Francisco Public Library. Thanks for Everything, Noxeema, Vida, and Chi-Chi travel African American Center, Main across the US to make it big in Hollywood! Then thunder your way down under to see how queens in Australia THURSDAY JUNE 7, 12:00-2:00 PM take their show on the road in The Adventures of Priscilla, *Thursdays at Noon Films: One Wedding and a Queen of the Desert. Dress up, dress down, come as you Revolution - On Feb. 12, 2004, pioneering lesbian are with an open heart and mind. activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon are officially wed by Excelsior San Francisco City Hall officials on their 51st anniversary, after then-Mayor Gavin Newsom makes the historic TUESDAY JUNE 5, 6:00-7:30 PM decision to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. -

Lgbtq Abyss Zignego Ready Mix, Inc

Democratic Socialists of America: Communism for the New Millennium • The Racist American Flag? August 5 , 2019 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH “DRAG”ING KIDS INTO THE LGBTQ ABYSS ZIGNEGO READY MIX, INC. W226 N2940 DUPLAINVILLE ROAD WAUKESHA, WI 53186 262-542-0333 • www.Zignego.com RESCUING OUR CHILDREN SUMMER TOUR 2019 WITH ALEX NEWMAN There is a reason the Deep State globalists sound so confident about the success of their agenda — they have a secret weapon: More than 85 percent of American children are being indoctrinated by radicalized government schools. In this explosive talk, Alex Newman exposes the insanity that has taken over the public school system. From the sexualization of children and the reshaping of values to deliberate dumbing down, Alex shows how dangerous this threat is — not just to our children, but also to the future of faith, family, and freedom — and what every American can do about it. VIRGINIA OREGON ✔ May 27 / Hampton / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 ✔ July 10 / King City / Sally Crino / 503-522-3926 ✔ May 29 / Chesapeake / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 WASHINGTON ✔ May 30 / Richmond / Thomas Redfern / 804-722-1084 ✔ July 12 & 13 / Spokane / Caleb Collier / 509-999-0479 ✔ June 4 / Falls Church / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 ✔ July 14 / Lynnwood (Seattle) / Lillian Erickson / 425-269-9991 CONNECTICUT CALIFORNIA ✔ June 7 / Hartford / Imani Mamalution / 860-983-5279 ✔ July 18 / Lodi / Greg Goehring / 209-712-1635 ✔ June 8 / Hartford / Imani Mamalution / 860-983-5279 ✔ July 23 / Thousand Oaks -

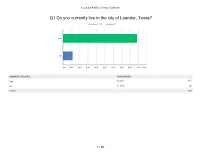

Leander Public Library Feedback Survey

Leander Public Library feedback Q1 Do you currently live in the city of Leander, Texas? Answered: 740 Skipped: 1 Yes No 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Yes 88.38% 654 No 11.62% 86 TOTAL 740 1 / 97 Leander Public Library feedback Q2 How often do you or your family members visit Leander Public Library? Answered: 740 Skipped: 1 Every day A few times a week About once a week A few times a month Once a month Less than once a month 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Every day 0.95% 7 A few times a week 9.19% 68 About once a week 12.43% 92 A few times a month 25.41% 188 Once a month 18.38% 136 Less than once a month 33.65% 249 TOTAL 740 2 / 97 Leander Public Library feedback Q3 How many times have you or your family members checked out a library book? Answered: 738 Skipped: 3 Every day A few times a week About once a week A few times a month Once a month Less than once a month 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Every day 0.54% 4 A few times a week 4.47% 33 About once a week 11.11% 82 A few times a month 22.90% 169 Once a month 16.94% 125 Less than once a month 44.04% 325 TOTAL 738 3 / 97 Leander Public Library feedback Q4 Please select any library events you or your family members have attended at Leander Public Library in the past: Answered: 602 Skipped: 139 Baby & Me LEGO Lab Gaming for Grown-Ups Adult Book Club Teen Anime Club Dinner and a Movie Leander Writers' Guild A Universe of Stories Frogs, Scales, & Puppy Dog.. -

Drag Queen Storytimes

NEWS DRAG QUEEN STORYTIMES EDITOR’S NOTE: An increasing By the end of the event, three Jacksonville, Florida number of challenges to free expression more protesters showed up, includ- “Storybook Pride Prom” at Willow- focus on “drag queen storytimes,” where ing frequent Vallejo Times-Herald branch Library in Riverside, sched- the target is usually not the titles, con- letter-to-the-editor writer Ryan uled for Friday, June 28, 2019, was tents, nor authors of any specific books, but Messano, who often rails against cancelled on Monday, June 24, after rather who is reading them. In this version homosexuals and other issues he the library had received hundreds of of storytimes where picture books are read believes are leading the country down phone calls supporting and protesting aloud to children, performers dressed in a negative path. the event. drag (usually men dressed in theatrically One of the counter-protesters was In a switch from a typical drag feminine costumes) try to encourage both a Michael Wilson of Vallejo, aide to queen storytime, in which an adult love of reading and acceptance of diver- Solano County Supervisor Erin Han- dressed in drag reads to young chil- sity. Some of the performers and events are nigan and the city’s second openly gay dren, the Storybook Prom planned affiliated with Drag Queen Story Hour, a Councilman in the early 2000s. to give the hundred teenagers who network of local organizations that began “I’m an advocate of Pride Month signed up a chance to dress as their in San Francisco; others are independent.