Creed and Company Limited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teletypewriter Communication Codes

Teletypewriter Communication Codes Gil Smith [email protected] 2001 (Document Notes) Abstract Preliminary -- 5/01 gil smith Corrections or comments to [email protected] This information is pulled from a variety of sources, such as various emails of the greenkeys group. For more discussion of teletypewriter code development, see: http://www.nadcomm.com/fiveunit/fiveunits.htm http://fido.wps.com/texts/codes/index.html http://www.science.uva.nl/faculteit/museum/DWcodes.html FIVE-UNIT CODES: USTTY and ITA2 (aka BAUDOT) There were a few variations in character codes for five-level teletypewriter machines. The two most-common character codes were ITA2 and USTTY (a variation of ITA2). The USTTY and ITA2 5-level teletypewriter codes are commonly referred to as "Baudot" codes. While this is technically incorrect, these popular 5-level codes evolved from the work of Jean Maurice Emile Baudot of France - - it seems fitting to accept the defacto reference to "Baudot" as implying USTTY or ITA2 codes, since they were the 5-level codes that saw practical use in teletypewriter systems. However, the true Baudot code dates to around 1874, when Baudot designed the "Baudot Multiplex System," a printing telegraph. The system used a 5-level code generated by a device with five keys, operated with two left-hand fingers, and three right-hand fingers -- this required great skill on the part of the operator who entered the code directly. However, it was still a major improvement in communications -- prior to Baudot's design, communication was carried out using Morse code with a telegraph key. The 5-level "Baudot" code was actually designed by Johann Gauss and Wilhelm Weber. -

IBM 1401 System Summary

File No. 1401-00 Form A24-1401-1 Systems Reference Library IBM 1401 System Summary This reference publication contains brief descriptions of the machine features, components, configurations, and special features. Also included is a section on pro grams and programming systems. Publications providing detailed information on sub jects discussed in this summary are listed in IB~I 1401 and 1460 Bibliography, Form A24-1495. Major Revision (September 1964) This publication, Form A24-1401-1, is a major revision of and obsoletes Form A24-1401-0. Significant changes have been made throughout the publication. Reprinted April 1966 Copies of this and other IBM publications can be obtained through IBM Branch Offices. Address comments concerning the content of this publication to IBM Product Publications, Endicott, New York 13764. Contents IBM 1401 System Summary . ........... 5 System Concepts . ................ 6 Card-Oriented System .... ......... 11 Physical Features. 11 Interleaving. .. .................................... 14 Data Flow.... ... ... ... ... .. ... ... .. ................... 14 Checking ................................................... 15 Word Mark.. ... ... ... ... ... ... .. ... ... ... ........... 15 Stored-Program Instructions. .................. 15 Operation Codes . .. 18 Editing. .. ............ 18 IBM 1401 Console ............................................ 19 IBM 1406 Storage Unit. ........................... 20 Magnetic-Tape-Oriented System . ........................... 22 Data Flow ................................................. -

Computer Programs for the Digitizing ~ and Using of Library Tapes of Ship 1 Stress and Environment Data

SC-237 I I COMPUTER PROGRAMS FOR THE DIGITIZING ~ AND USING OF LIBRARY TAPES OF SHIP 1 STRESS AND ENVIRONMENT DATA I This document has been approved for public release and sale; its distributionis unlimited. SHIP STRUCTURE COMMITTEE 1973 SHIP STRUCTURE COMMITTEE Ati INTERAGENCY ADVISORY COMMITTEE DEOICATEO TO IMPROVING THE STRUCTURE OF SHIPS MEMBER AGENCIES, ADDRESS CORRESPOtlOENCE TO: LINIICDSTATESCOASTGUARD SECRSIARY NAVALSI+IPSYSTEMSCOMMAND SHIP STRUCTURE COMMITTEE MIIITARYSEALIFTCOMMAND u.S.COASTGUARDHEADOUARIERS MAII1!MEADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D.c.XM4k 20590 AMFRI(:ANBUREAUOFStilppING I This report k the companion to SSC 236, a Method for Digitizing, Preparing and Using Library Tapes of Ship Stress and Environment Data, and cent ains the details of the conversion program which has been developed to increase the usefulness of full scale hull s tress, ship motion and environmental information which has been obtained over the last several years. Rear Admiral, U. S. Coast Guard Chairman, Ship Structure Committee SSC-237 Final Technical Report on Project SR-187, “Ship Response Data Study” PART II COMPUTER PROGRAMS FOR THE DIGITIZING AND USING OF LIBRARY TAPES OF SHIP STRESS AND ENVIRON- MENT DATA by Aldie E. Johnson, Jr. James A. F1aherty Isaac J. Walters Teledyne Materials Research under Department of the Navy Naval Ship Engineering Center Contract No. NOO024-69-C-5161 This document has been approved for public release and sale; its distribution is unlimited. U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters Washington, D.C. 1973 ABSTRACT Details of computer programs and their operating instructions are given for the processing of logbook-type data and associated analogue stress signals into digital format. The logbook data is keypunched, edited and formatted for subsequent merging with the analogue signal which has been pro- cessed through an Analogue-to-Di gital (A/D) converter. -

An Introduction to Teleprinters and Punched Tape Equipment

1st Edition . April 1956 2nd Edition . January 1958 Digital Recreation - Sam Hallas (G8EXV): April 2008 BULLETIN PT56 (Ed. 2) . JANUARY 1958 an introduction to TELEPRINTERS and PUNCHED TAPE EQUIPMENT TELEGRAPH HOUSE CROYDON, ENGLAND TELEPHONE : CROYDON 2121 (10 LINES) TELEGRAPHIC ADDRESS : CREDO, TELEX, CROYDON TELEX : 28836 © 1958 by Creed & Company Limited 1 2 CONTENTS PAGE 5 Introduction Part I: Teleprinters A. BASIC PRINCIPLES 7 Definitions 7 Intelligence 9 Teleprinter Code 11 Start-Stop Principle 11 Telegraph Signals 17 Telegraph Speed B. OUTLINE DESCRIPTION OF A TELEPRINTER 15 Stages of Transmission 16 Keyboard 16 Receiver Part II: Punched Tape Equipment C. PUNCHED TAPE TECHNIQUE 20 Kinds of Punched Tape 22 Methods of Coding Information on Punched Tape D. TYPES OF PUNCHED TAPE EQUIPMENT 28 Keyboard Perforators 30 Tape Readers 34 Perforator-Readers 35 Reperforators 39 Auxiliary Equipment E. APPLICATIONS TO DIGITAL COMPUTERS 41 Input Preparation 48 Input Transmission 49 Output Recording and Printing F. FURTHER PUNCHED TAPE APPLICATIONS 50 Punched Tape-Punched Card Systems 50 Mechanised Addressing Equipment 51 Process Control 3 4 INTRODUCTION Creed Teleprinters and Punched Tape equipment were originally developed for use in the telegraph communication field and they have been increasingly used ever since in telegraph systems all over the world. During recent years, however, their use has been extended beyond this tradi- tional field to a rapidly growing number of non-telegraphic applications such as the provision of input and output facilities for digital computers and the increased automatisation of existing systems such as punched card accounting and mechanised addressing. As a result of this sudden increase in the number of applications that are being found for Teleprinters and Punched Tape, considerable interest is being shown in this equipment by engineers and others who wish to discover whether it can be applied to their own special problems but who lack sufficient knowledge of the basic principles involved to permit them to do this. -

Nsa/Css Policy Manual 9-12 Storage Device Sanitization and Destruction Manual

UNCLASSIFIED NSA/CSS POLICY MANUAL 9-12 STORAGE DEVICE SANITIZATION AND DESTRUCTION MANUAL PUBLICATION INFORMATION DATE: 4 December 2020 (See Document History.) OFFICE OF PRIMARY Center for Storage Device Sanitization Research INTEREST: (301) 688-1053, 977-7113 (secure) RELEASABILITY: NSA/CSS Policy Manual 9-12 is approved for public release. The official document is available on the Office of Policy (P12) website (“go policy”). AUTHORITY: Anne Neuberger, Director, Cybersecurity ISSUED: 4 December 2020 PURPOSE AND SCOPE 1. This policy manual provides routine guidance for sanitization of information system (IS) storage devices for disposal or recycling in accordance with Department of Defense (DoD) Manual 5200.01, Volume 3, “DoD Information Security Program: Protection of Classified Information” (Reference a), Intelligence Community Standard 500-34, “Electronic Waste (E- Waste) Management and Disposal” (Reference b), and NSA/CSS Policy 9-12, “Storage Device Sanitization and Destruction” (Reference c). Information stored on these devices may range from UNCLASSIFIED to TOP SECRET and may include compartmented, sensitive, or limited- distribution material. Furthermore, this manual provides information about how to obtain current listings of evaluated sanitization equipment that meets NSA/CSS specifications. 2. This manual applies to all NSA/CSS elements, contractors, and personnel, and pertains to all IS storage devices that they use. UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Policy Manual 9-12 4 December 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Publication Information .............................................................................................................. -

Iechnicol Description

lqcll#n 047 Iechnicoldescription Edilion3 SCOPEOF THE MANUAL This document describes both the Facit 4046 punch and the requirementsto externalequipment. This docu'ment does not Facit 4047 Reader/Punch Combination. lt includes detailed includedetailed circuit diagrams or circuitdescriptions, and operating information, interconnectiondetails and interfacing doesnot includesofware descriptions or servicinginformation. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5.10 ProgramMode22 5.1 1 Error Message 2. DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION 2.1 B rief Description 6. CODE CONVERSION 2.2 Punch Tape Handling 6.1 ASCII to ASCII 2.3 Punch Tape Loading 6.2 ASCII to Telex (5 track) 2.4 PunchingAccuracy 6.3 ASCII to Telex (USA -8 track RS358) 2.5 ReaderTape Handling 6.4 ASCllto EIA (RS244) 2.6 ReaderTape Loading 6.5 EIA (R5244) to ASCII 3. OPERATION 7. TELEX TAPE FORMATTING 3.1 Punch Buffer 7 .1 ClearText Punching 7.2 Message 3.2 PunchingOut Data End of Code 7.3 Time Function 3.3 Buffer Status Signalling Out 7 3.4 Punch Speed .4 Line Length Adjustment 7.5 Expansion 3.5 Time Out Code 7.6 Reduction of Spaces 3.6 Tape Reader (Facit4047 Combination Onlv) B. TEST MODE 4. KEYBOARD CONTROLS 8.1 Test Mode 1 - Memory Test (Facit 4.1 Key Functions 40461 8.2 Test Mode 2 - Channel 1 Communication Test 4.2 Key Functions(Facit 4047 Combination) 8.3 Test Mode 3 - Channel2 Communication Test 8.4 Test Mode 4 - Test Tape Punching 5. PROGRAM MODE 8.5 Test Mode 5 - Test Tape Reading 5.1 SelectModes in Sequence 8.6 Test Mode 6 - SingleTrack Punching 5.2 SelectMode Directly 8.7 Test Mode 7 - ContinuousTest Tape Punching 5.3 ChangeParameter Value 5.4 ProgramModes 1 to 4 9. -

Univac Scientific Computing System Model 1103A, 1957

Optional Equipment Optional Equipment The computing system . The Input Section feeds rapid access magnetic core memory, a large capacity data and computer instructions into the system. drum memory, and for maximum storage capacity This section receives data from a wide variety of . ..magnetic tape. The Arithmetic Section. sources, among which are magnetic tape, punched When the computing process (referred to as the cards, or on punched paper tape. The Con- program) has been initiated, the arithmetic section trol Section is the "organizer" for all of the processes performs all of the operations of addition, sub- occurring within the computing system. This section traction, multiplication, and division . as well receives all of the instructions which the computer as some strictly logical operations such as shifting, is to carry out, interprets them, and directs their logical addition, and logical multiplication. This execution. The Storage Section receives and section produces the answers to the mathematical stores all of the data which is to be operated upon. problems. Output Section. The results of Its most important function is to store all of the the computations are transmitted to one or more information and instructions which will be used in units of output equipment. This equipment may the solution of the problem. This section supplies store results on magnetic tape, on punched cards, these data to the other sections in the computer on punched paper tape, or print the information as required. All information stored within the com- on rolls or continuous forms in several copies. The puter is easily accessible through a system of data may also be translated into plotted graphs or unique addresses. -

Network Storage 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NETWORK STORAGE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James OReilly | 9780128038659 | | | | | Network Storage 1st edition PDF Book Sorry, this product is currently out of stock. Electricity transmission and distribution systems carry electricity from suppliers to demand sites. Categories : Network-attached storage Server appliance Software appliances. Updating Results. Clustered NAS, like a traditional one, still provides unified access to the files from any of the cluster nodes, unrelated to the actual location of the data. Following the Newcastle Connection, Sun Microsystems ' release of NFS allowed network servers to share their storage space with networked clients. NAS is designed as an easy and self-contained solution for sharing files over the network. Advanced grid technologies to sustain higher network efficiency and maintaining power quality and security are under development. NAS units rarely limit clients to a single protocol. Imprint: Morgan Kaufmann. Paper data storage media. Computer data storage server. This book explains the components, as well as how to design and implement a resilient storage network for workgroup, departmental, and enterprise environments. All Pages Books Journals. Jim is currently a consultant specializing in storage systems, virtualization, infrastructure software, and cloud hardware. All Pages Books Journals. Enterprise storage architects, designers, and managers, as well as executives will find "Resilient Storage Networks" both interesting and informative. President, Volanto, USA. IT managers and administrators, network system sales and marketing staff, network system integrators and support staff, Networking students, faculty, and researchers. Be the first to write a review. About Overview Electricity transmission and distribution systems carry electricity from suppliers to demand sites. In an appropriately configured RAID array, a single bad block on a single drive can be recovered completely via the redundancy encoded across the RAID set. -

The History of the Data Systems Autochemistâ® (ACH) And

244 © 2014 IMIA and Schattauer GmbH The History of the Data Systems AutoChemist® (ACH) and AutoChemist- PRISMA (PRISMA®): from 1964 to 1986 L. Ohlsén, I. Jungner, H. E. Peterson Stockholm, Sweden Summary mass scale using complete laboratory automa- 1 Introduction tion [9-12]. In 1962-64, the Swedish National Objectives: This paper presents the history of data system develop- During the 1950’s, the demand for labora- Board of Health entrusted them to carry out ment steps (1964 – 1986) for the clinical analyzers AutoChemist®, tory analyses drastically increased among blood analyses - 12 tests - on 90,000 Swedes, and its successor AutoChemist PRISMA® (PRogrammable Individual- primary care providers and hospitals. The aged 25 and above: the Varmland Project [12- ly Selective Modular Analyzer). The paper also partly recounts the workload at many laboratories became an 17]. For this purpose, the Jungner brothers history of development steps of the minicomputer PDP 8 from Digital increasing burden. An important evolution built a special equipment system capable of Equipment. The first PDP 8 had 4 core memory boards of 1 K each was the invention in 1957 by Skeggs [1) of performing automatic blood analyses with a and was large as a typical oven baking sheet and about 10 years the discrete sample analyzer (offered since fixed analyses program, the first 12-channel later, PDP 8 was a “one chip microcomputer” with a 32 K memory 1958 for sale as AutoAnalyzers® from Tech- multi-analyzer [12]. This was comprised in chip. The fast developments of PDP 8 come to have a strong influence nicon Instruments Corp.). -

The Good Old Days Ewart Matthews

The good old days Ewart Matthews It was my good fortune to be part of the earliest days of the computer age, from the birth - almost - of computers as we know them today. Of course I was not involved in the development of the initial concept, but came on the scene when computers were sufficiently advanced to be taken out of the hands of the "eggheads" and into the clutches of ordinary mortals. Someone, somewhere took a great leap forward and after years of experimentation, finally decided to allow a normal, business person to control one of these hideously expensive devices and use it to process business data. Installing and running a system You could not simply plug one of these behemoths in and boot in a program. Programs as such did not exist in the commercial world. Office and accounting work was done manually by clerks. At the start, no one knew how to make a machine do all the individual tasks that were being done manually. So, not surprisingly, many mistakes and disasters accompanied the learning process. Nor were there any compilers to put things together. You worked out what you wanted the machine to do in a rough kind of way using hand drawn charts, and then transposed this into a program, written in machine language. You typed the program into a typewriter that also punched paper tape. The paper tape was then fed into the computer on using a "high speed" tape reader. This was followed by an agonising process of trial and error, using sample data, before live data was used to produce a real result. -

An Introduction to Creed Teleprinters 1966

.--------------------. r I ' An introduction to Creed teleprinters and punched paper tape equipment An introduction to Creed teleprinters and punched paper tape equipment CONTENTS Introduction What is a teleprinter?- The teleprinter code 2 Start/stop principle- Telegraph signals 3 Telegraph speed- Outline description of a teleprinter- Stages of transmission 4 Keyboard - Receiver 5 Punched tape technique- Kinds of punched tape- Methods of coding information on punched tape 6 Applications to digital computers Input preparation- Manual tape preparation- Tape editing 10 Output recording and printing Model Seventy-five interpreter set Model Seventy-five 5-wire reproducer set 11 The equipment- A short introduction to each of the major Creed machines 12 Glossary of terms 16 INTRODUCTION Creed teleprinters and punched paper tape equipment were originally devel oped for use in the telegraph com munication field and they have been increasingly used ever since in telegraph systems all over the world. During recent years, however, their use has been extended beyond this traditional field to a rapidly growing number of non-telegraphic applica tions such as the provision of input and output facilities for digital com puters and the automation of existing systems such as punched card accounting and mechanised addressing. As a result of this sudden increase in the number of applications that are being found for teleprinters and punched tape, considerable interest has been shown in this equipment by engineers and others who wish to discover whether it can be applied to their own special problems. This bulletin has been written princi pally for such readers and others who need to know of the basic principles used in teleprinter communications systems. -

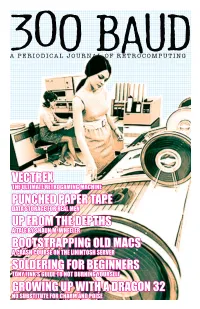

Vectrex Punched Paper Tape up from the Depths

VECTREX THE ULTIMATE RETROGAMING MACHINE PUNCHED PAPER TAPE DATA STORAGE FOR REAL MEN UP FROM THE DEPTHS A TALE BY SHAUN M. WHEELER BOOTSTRAPPING OLD MACS A CRASH COURSE ON THE LININTOSH SERVER SOLDERING FOR BEGINNERS TONY FINK’S GUIDE TO NOT BURNING YOURSELF GROWING UP WITH A DRAGON 32 NO SUBSTITUTE FOR CHARM AND POISE #"6% HOW TO MAKE FRIENDS AND INFLUENCE PEOPLE IN THE 1980s by Dale Goodfellow Watty was impressed. ladies (well that would have came later, you ISSUE #1 - January 2010 understand - I was still a boy) and in general we have, I would state, a moral right to duplicate Ever since he realised, when we were about offer me many of the societal rewards that and distribute these historical works. I would also 10 years old, that I was in fact not ‘hard’ an eleven year old desires. FINDERS KEEPERS extend this to cover books and magazines, the but just fat, and had ‘battered’ me, I had an I know its theft, I just don’t care! recognised ephemera of all ages. apprehensive relationship with him. I always All of these things were easily within my felt that it could turn violent at any time. grasp... We may as well tackle this one straight off the bat. The people and the skills needed to start from To state the case; to make the point; to clarify the scratch on a Z80 and a 6502 are disappearing as sentiment; to justify our indifference to Intellectual each year passes. Individuals who, while having a Watty was impressed and this was good, as Only one thing stood in my way – I had a property rights..