Projects on the Geometry of Perception and Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Audiences?

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? Full Report Introduction • New Zealand On Air (NZ On Air) supports and funds audio and visual public media content for New Zealand audiences. It does so through the platform neutral NZ Media Fund which has four streams; scripted, factual, music, and platforms. • Given the platform neutrality of this fund and the need to efficiently and effectively reach both mass and targeted audiences, it is essential NZ On Air have an accurate understanding of the current and evolving behaviour of NZ audiences. • To this end NZ On Air conduct the research study Where Are The Audiences? every two years. The 2014 benchmark study established a point in time view of audience behaviour. The 2016 study identified how audience behaviour had shifted over time. • This document presents the findings of the 2018 study and documents how far the trends revealed in 2016 have moved and identify any new trends evident in NZ audience behaviour. • Since the 2016 study the media environment has continued to evolve. Key changes include: − Ongoing PUTs declines − Anecdotally at least, falling SKY TV subscription and growth of NZ based SVOD services − New TV channels (eg. Bravo, HGTV, Viceland, Jones! Too) and the closure of others (eg. FOUR, TVNZ Kidzone, The Zone) • The 2018 Where Are The Audiences? study aims to hold a mirror up to New Zealand and its people and: − Inform NZ On Air’s content and platform strategy as well as specific content proposals − Continue to position NZ On Air as a thought and knowledge leader with stakeholders including Government, broadcasters and platform owners, content producers, and journalists. -

View Annual Report

ANNUSKY NETWORKA TLELEVI REPOSION LIMITEDRT JUNE 2013 EVEry Day we’RE ON AN ADVENTURE LESLEY BANKIER FanaticalAS THE about RECEPTIONI Food TV ST I love sweet endings. Whether I’m behind the front desk or attempting recipes from Food TV, I’ll do my best to whip it all into shape and serve it with a smile. COME WITH US EVEry Day we’RE ON AN ADVENTURE FORGING NEW GROUND AND BRINGING CUSTOMERS EXPERIENCES THEY NEVER KNEW EXISTED NADINE WEARING FanaticalAS THE about SENIO SKYR Sport MARKETING EXECUTIVE I’m passionate about getting the right message, to the right person, at the right time. Especially on a Saturday night when the rugby is on SKY Sport. Run it Messam! Straight up the middle! COME WITH US FORGING NEW GROUND AND BRINGING CUSTOMERS EXPERIENCES THEY NEVER KNEW EXISTED TOGETHER WE CAN GO ANYWHERE 7 HIGHLIGHTS 8 CHAIRMAn’S LETTER 10 CHIEF Executive’S REVIEW 14 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 16 BUSINESS OVERVIEW 22 COMMUNITY AND SPONSORSHIP 24 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 30 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 33 2013 FINANCIALS 34 Financial Trends Statement 37 Directors’ Responsibility Statement 38 Income Statement 39 Statement of Comprehensive Income 40 Balance Sheet 41 Statement of Changes in Equity 42 Statement of Cash Flows 43 Notes to the Financial Statements 83 Independent Auditors’ Report 84 OTHER INFORMATION OPENING 86 Corporate Governance Statements 89 Interests Register CREDITS 91 Company and Bondholder Information 95 Waivers and Information 96 Share Market and Other Information 97 Directory 98 SKY Channels SKY Annual Report 2013 6 | HIGHLIGHTS TOTAL REVENUE TOTAL SUBSCRIBERS $885m 855,898 EBITDA ARPU $353m $75.83 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE NET PROFIT $82m $137.2m EMPLOYEES FTEs MY SKY SUBSCRIBERS 1,118 456,419 SKY Annual Report 2013 | 7 “ THE 17-DAY COVERAGE OF THE LONDON OLYMPICS WAS UNPRECEDENTED IN NEW ZEALAND .. -

Commodity Update

Eco Outlook Vol. 28, No. 12 Restaurant numbers held steady in Oct. The Financials or fundamentals? The financial NRA’s Restaurant Performance Index December 12, 2018 markets are running scared. Stocks are de- edged up 101.2 in Oct from 101.1 in Sept. clining and the yield gap between long and According to TDn2K’s Black Box Intelli- Happy Holidays! short-dated U.S. Treasury securities is gence index, year-over-year same-store shrinking. Both of these financial indicators sales were up just 1.0% in Nov, following a have been precursors to past recessions. Oil Highlights: 0.8% gain in Oct. Customers, however, re- prices plummeted in Oct/Nov, signaling main elusive. Year-over-year traffic de- weaker global demand and a supply glut. Christmas trees clined 1.9% in Nov after a 2.2% decline in Other investors’ anxieties include spiraling Oct. Labor will again be the biggest chal- in short supply U.S. debt levels, the U.S. China trade-war/ page 1 lenge in 2019. According to the Bureau of cold-war, a deteriorating Trump presidency Labor Statistics, there were 1,040,000 un- and the impending Brexit disaster for the filled “accommodation and food service” U.K. However, at least for 2019, economic jobs on Nov 1, up 25% from a year ago. OPEC / Russia cut fundamentals tell a different story. crude oil output The Grinch may have gotten his greedy fin- page 2 Studies by economists at both UBS Securi- gers into this year’s Christmas tree market. ties and J.P. -

AUTUMN 2019 Best Estate Agent in Central London &

NO. 174 THE CLARION CALL OF THE SOHO SOCIETY The Soho Society’s Free and yet Priceless Magazine AUTUMN 2019 Best Estate Agent in Central London & greaterlondonproperties.co.uk Soho Clarion Autumn 2019 Editorial 3 From Soho Society Chair Tim Lord The Club, Leo Damrosch 25 Book Review NEWS Our community updates inclduing licensing, planning, Tehran 4 police and messages from Soho Councillors 26 David Gleeson Thank You for the Soho Fete FEATURES 28 Photographs from the 45th Soho Fete Bar Italia 70 Years On 10 Jane Doyle speaks to Anthony Polledri Simon Buckley 30 A message from St Anne’s Church Berenjak 12 Restaurant Review St Anne’s Day 31 Hugh Morgan Walking 13 Reminiscences from Soho’s past 20th Century Fox 32 A history School Garden & Food Feast 14 An update from the parish school Map 34 The Soho Society’s preferred providers Keeping Soho Special 20 The Soho Society’s preferred providers The 43 Club 35 Celebrating Kate Meyrick Theatre, Museums & Galleries 21 A roundup from Jim Cooke 40 Years Ago Today 36 The Soho Clarion, 1979 Soho Swap Shop 22 Lucy Haine RECIPE Tomato Chutney When Soho Lost It’s Louche 15 The Soho Bakers Club 23 Poet Jo Reed INTERVIEW Last Week on Berwick Street Colin Vaines 24 Steve Head 16 Film producer and long time Soho resident Cover image (repeated on page 32): Jenn Lambert @sohosketchbook THE SOHO SOCIETY St Anne’s Tower, 55 Dean Street, London W1D 6AF | Tel no: 0300 302 1301 [email protected] | Twitter: @sohosocietyw1 Facebook: The Soho Society | www.thesohosociety.org.uk CONTRIBUTORS Tim Lord | Jane -

SOHO Reflections Newsletter, Vol. 10, Issue 12

THE 5.0.H.0.. NEWSLETTER REFLECTIONS DECEMBER 1978 SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA 92103 (714) 223-1997 Celebrate Christmas with SOHO at our~ . annual Christmas party! It will be .\ •• , held in Kensington this year at the 1 11 ~\! \\ \~· home of Bob and Ingrid Coffin, at \l, . 4321 Alder Drive, on Saturday, December 1 16, 1 \ /- ~ \\ ~ from 7 to 10 p. m. I \ ·1, \ All members and their guests are joytu lly I I . .·'/ invited to share in the festivities of the season < , .,.,\1 a.t this beautiful Spanish Colonial Kensington Rim '\\\t Home, built in 1929 for President Rubio of Mexico as \ "\'.~his retirement house. (President from 1930-1932). I The present owners, the Coffins, have graciously opened their home for the party. They own the Glass Gallery, a stained glass studio, and guests will be able to appreciate a mini-tour of the houseful of antiques from Art Deco to Victoriana -- in this lovely .. canyon home. l ~)I, I 1 Members are asked to bring a tray of hors doeuvres to share, ana'1iquid refreshment will be provided. Surprise enter _tainment as well I All those . who would like to hostess are asked to call Claire Kaplan at 286-8836. We ~ to see you there to celebrate the holiday season! · \ t..::il(,Aif?Yi'6 ,. , See Map on Page 5. newsBRIEF .S PHOTOGRAPHER1/A:-TTSD ! F INT ZELBERG APPOIN TED SOHO is in great need of an TO FILL VACANCY on-going photographe~ to add his or her tale nt s to our g~aphic Nick Fintzeiberg, former Presicien: records and co the ~ewsle:ter! •)f SOHO an d current Board member, was named Vice-President for Governmental Anv member whc would like t o take Affairs by President Pat Schae lchlin at pictures of events, struct~res, the October 30 Board Meeting. -

Design Museum Selects Its Picks of the Year

Edition: UK Sign in Mobile About us Today's paper Subscribe T his sit e uses co o kies. By co nt inuing t o bro wse t he sit e yo u are agreeing t o o ur use o f co o kies. Find o ut mo re here Your search terms... Art and design Search News Sport Comment Culture Business Money Life & style Travel Environment Tech TV Video Dating Offers Jobs Culture Art and design Design Share 15 Design Museum selects its picks of the Today's best video year T weet 27 The Designs of the Year contenders include the Olympic 2 cauldron and Beijing's Galaxy Soho building Sharre 2 Email Oliver Wainwright The Guardian, Tuesday 19 March 2013 23.09 GMT Jump to comments (0) Article history Art and design T he week in T V Design Telly addict Andrew Collins reviews MasterChef, In the Flesh, Prisoners' Wives and It's Kevin (pictured Cult ure above) Awards and prizes 59 comments UK news Diana's dresses at auct io n in Lo ndo n Mo re news Ten dresses worn by the Princess of Wales go under the hammer Mo re o n t his st o ry Ko mo do drago n babies hat ch at zo o Seven baby komodo dragons successfully hatched at a zoo in Indonesia Designs of the Year Designs of the Year contenders 2013 – in pictures Bees halt f o o t ball Take a look at some of mat ch A f olding wheel, a non-stick ketchup bottle and a chair made f rom sea the world's best Swarm forms colony waste are some of the more innovative products unveiled today at the design, from London's on a crossbar before Olympic cauldron to Design Museum's annual designs of the year exhibition, which this kick-off at a game in Australia's gruesome Brazil year sees a welcome emphasis on practical problem-solving rather anti-smoking than f antastical f orms. -

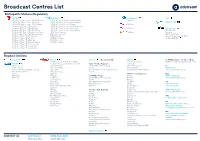

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Glynn Lavender: Adventurer (And Teacher) with a Camera PRODUCED BY

MASTERS JONATHAN THORPE TARA RUBY NADER ABUSHHAB JUSTIN HAUGEN ARPAN DAS ALYCE BENDER SHANE RUSSECK AARON ANDERSON GREGORY BORATYN ALEX CEARNS MAXIM GUSELNIKOV LISA LANGELL Glynn Lavender: Adventurer (and teacher) with a Camera PRODUCED BY MASTERS SERIES CONTENTS 7 7 Glynn Lavender: Adventurer (and Teacher) with a Camera 11 The Cinematic Vision of Jonathan Thorpe 15 Tara Ruby’s Salute to Life 19 Nader Abushhab’s Portraits in Honesty 23 Justin Haugen: Wedding Photography 15 with a Southwest Flair 27 Arpan Das Views the Heavens Above and the Beautiful Landscapes Below 31 How Alyce Bender Makes Peace with Nature Through Photography 35 Shane Russeck on Seeking the Hidden Beauty of Danger 39 39 The Extreme Talents of Aaron Anderson 43 Exploring the Paths Less Taken with Gregory Boratyn 47 Alex Cearns Has Gone to the Dogs (and Other Critters), in a Good Way 51 Maxim Guselnikov, From Russia with Love (and Talent) 55 Lisa Langell Going Where the Wild Things Are Tamron Masters is produced by Pro Photo Daily. 43 All profiles are written by Jeff Wignall. © Philip Ruopp Di For full-frame SonyIII mirrorless The perfect trio for Sony mirrorless cameras. 17-28mm 28-75mm 70-180mm F/2.8 Di III RXD [Model A046] F/2.8 Di III RXD [Model A036] F/2.8 Di III VXD [Model A056] ONLY AVAILABLE AT YOUR www.tamron-usa.com AUTHORIZED TAMRON USA RETAILER MASTERS SERIES we can put the skills learned in the workshops into practice.” Glynn Lavender: Lavender is heavily involved in the photographic industry worldwide as Adventurer (and teacher) former president of the Digital Image Marketing Association, Chairman of with a Camera By Jeff Wignall the PMA Education Committee as well as several other positions with Glynn Lavender possesses an impressive the Australian branch of the Photo Marketing Association. -

STEREO 2017 Senior Review Proposal

STEREO A PROPOSAL TO THE SENIOR REVIEW OF HELIOPHYSICS OPERATING MISSIONS FEBRUARY 2017 Analysis of the interactions of three CMES made possible by STEREO. Interaction of CME-3 (blue) with CME-1 (magenta) and CME-2 (green) at 6.8, 13.4, and 13.1 R☉, respectively. The separate fronts of all three CMEs are most evident in the COR2-A (top right). From Colaninno & Vourlidas (2015). Table of Contents Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) 1 I. Executive Summary 1 II. Mission Status 2 IIa Launch, orbital design, and IMU 2 IIb Superior conjunction and science data return 2 IIc Status of the STEREO-B spacecraft 3 III. Science and Science Implementation 4 IIIa. Data Accessibility and Impact 4 IIIb. Assessment of scientific progress, FY2015 - FY2017 6 Goal Set 1: Characterize space weather throughout the inner heliosphere 6 Goal Set 2: What Can We Learn from 360° Coverage of the Solar Corona? 15 Goal Set 3: What can we learn from coverage of the full heliosphere? 17 IIIc. Scientific Impact of a One Spacecraft Mission 20 IIId. Scientific Productivity and Vitality 21 IIIe. Prioritized Science Goals, FY2018 - FY2022 21 New Goal Set 2: Studying the corona and solar wind at solar minimum 22 IIIf. Implementation 25 IV. Technical Implementation 27 V. Budget 29 VI. Appendices 35 A. Mission Archive Plan 35 B. STEREO Publication Record, 2015 - 2017 42 C. Spacecraft and Instrument Status as of 2017 Feb. 24 43 D. Research Focus Areas, NASA Heliophysics Roadmap, 2014 – 2033 (annotated) 46 E. Acronyms and Other Abbreviations 47 !ii Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) I. -

Subscription Video on Demand: Viewing Preferences Among New Zealand Audiences

Subscription Video on Demand: Viewing preferences among New Zealand audiences Rachel Hayley Daniels A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Communication Studies (MCS) 2017 School of Communication Studies Abstract With the development of digital television platforms in New Zealand and the launch of Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD) services such as Netflix NZ, Lightbox, Quickflix and Neon, a more discerning television audience is emerging. SVOD services are influencing a change within the television broadcasting landscape in New Zealand, fragmenting audiences away from traditional linear television, appealing to viewers in new and innovative ways and changing viewing behaviour. This thesis provides qualitative and quantitative analysis of SVOD viewers’ experiences, expectations, and behaviours with respect to viewing content on the digital platforms and services available to New Zealand subscribers. Quantitative data was collected from an online survey; participants were drawn from readers of the New Zealand Herald online. The quantitative data was collected in order to help position and supplement the qualitative data, which was obtained through focus group interviews. A thematic analysis was used to identify key themes and draw insight from the data sets. The thesis identifies that viewers place a high degree of preference and value on the freedom and opportunities that SVOD provides in personalizing their own viewing practices. Key preferences among these was the ability to control content selection and engage in the practice of anytime viewing, i.e. to choose from an increasingly broad selection of content wherever they are, whenever they like and on whatever device they prefer to view it on. -

The Film and Television Industry in London's Suburbs

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Galina Gornostaeva The film and television industry in London’s suburbs: lifestyle of the rich or losers’ retreat? Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Gornostaeva, Galina (2008) The film and television industry in London’s suburbs: lifestyle of the rich or losers’ retreat? Creative Industries Journal, 1 (1). pp. 47-71. ISSN 1751-0694 DOI: 10.1386/cij.1.1.47/1 © 2008 Intellect This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/22889/ Available in LSE Research Online: December 2009 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. The film and television industry in London’s suburbs: lifestyle of the rich or losers’ retreat? Galina Gornostaeva Abstract There is growing evidence of the decentralization of the film and television (FTV) industry in London. -

Maxtv Channel Line-Up

Channel Line-up maxTV Standard SD HD† CHANNELS SD HD† CHANNELS SD HD† CHANNELS 2 PVR Playback 41 341 Cartoon Network+ 273 RDI* 3 303 CBC*+ 43 343 CTV Life+ 274 CPAC French 4 304 CTV*+ 44 344 Cooking Channel+ 275 UNIS*+ 5 305 Global*+ 45 345 GameTV+ 276 AMI-télé*+ 6 306 ABC Boston 46 346 Local On Demand Featured* 280 The Miracle Channel 7 307 CBS Boston 47 347 Local On Demand* 282 Daystar 8 308 FOX Boston 48 348 maxTV Live Local 1+ 326 ABC Seattle 9 309 NBC Boston 49 349 maxTV Live Local 2+ 327 CBS Seattle 10 310 PBS Boston 53 353 BNN Bloomberg 328 FOX Seattle 11 311 YTV+ 58 Al Jazeera 329 NBC Seattle 12 312 MUCH+ 111 411 TSN 1+ 331 Citytv Toronto 13 313 MovieTime+ 112 412 TSN 2+ 332 CTV Toronto 14 314 CMT+ 113 413 TSN 3+ 333 Global Toronto 15 315 CBC News Network 114 414 TSN 4+ 337 CTV Vancouver 16 316 CTV News Channel+ 115 415 TSN 5+ 338 Global Vancouver 17 317 The Weather Network*+ 116 416 Sportsnet West+ 339 CBC Toronto 18 CPAC* 117 417 Sportsnet Pacifi c+ 340 CBC Vancouver 19 319 Citytv Saskatchewan*+ 118 418 Sportsnet East+ 342 PBS Seattle 20 320 Sask Legislature* 119 419 Sportsnet Ontario+ 554 AMI-tv*+ 21 321 The Shopping Channel+ 121 421 Sportsnet ONE+ 555 AMI-audio*+ 22 322 APTN* 127 427 Game+ 600 Pay Per View Listings 23 323 Vision TV+ 153 Stingray Retro 601 Pay Per View Preview 24 324 OMNI* 187 487 Movies On Demand Featured 602 605 Pay Per View 25 325 MTV+ 199 499 Movies On Demand Featured 603 606 Pay Per View 270 570 Radio-Canada* 661 662 Sportsnet Flames+ 271 TVA Montreal* 663 664 Sportsnet Oilers+ 272 572 TV5 Theme Packs SD