Cape of Storms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ultimate Digital Nomad Guide

THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL NOMAD GUIDE CAPE TOWN 2020 CAPE TOWN - NEW DIGITAL NOMAD HOTSPOT Cape Town has become an attractive destination for digital nomads, looking to venture to an African city and explore the local cultures and diverse wildlife. Cape Town has also become known as Africa’s largest tech hub and is bustling with young startups and small businesses. Cape Town is definitely South Africa’s trendiest city with hipster bars and restaurants along Bree street, exclusive beach strips with five star cuisine and rolling vineyards and wine farms. But is Cape Town a good city for digital nomads. We will dive into this and look at accommodation, co-working spaces, internet connectivity,safety and more. Let's jump into a guide to living and working as a digital nomad in Cape Town, written by digital nomads, from Cape Town. VISA There are 48 countries that do not need a visa to enter South Africa and are abe to stay in SA as a visitor for 90 days. See whether your country makes this list here. The next group of countries are allowed in for 30 days visa-free. Check here to see if your country is on this list. If your country does not fall within these two categories, you will need to apply for a visa. If you can enter on a 90 day visa you can extend it for another 90 days allowing you to stay in South Africa for a total of 6 months. You will need to do this 60 days prior to your visa end date. -

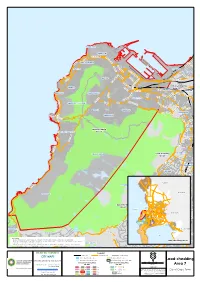

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus -

Applications

APPLICATIONS PUBLICATIONS AREAS BUSINESS NAMES AUGUST 2021 02 09 16 23 30 INC Observatory, Rondebosch East, Lansdowne, Newlands, Rondebosch, Rosebank, Mowbray, Bishopscourt, Southern Suburbs Tatler Claremont, Sybrand Park, Kenilworth, Pinelands, Kenwyn, BP Rosemead / PnP Express Rosemead Grocer's Wine 26 Salt River, Woodstock, University Estate, Walmer Estate, Fernwood, Harfield, Black River Park Hazendal, Kewtown, Bridgetown, Silvertown, Rylands, Newfields, Gatesville, Primrose Park, Surrey Estate, Heideveld, Athlone News Shoprite Liquorshop Vangate 25 Pinati, Athlone, Bonteheuwel, Lansdowne, Crawford, Sherwood Park, Bokmakierie, Manenberg, Hanover Park, Vanguard Deloitte Cape Town Bantry Bay, Camps Bay, Clifton, De Waterkant, Gardens, Green Point, Mouille Point, Oranjezicht, Schotsche Kloof, Cape Town Wine & Spirits Emporium Atlantic Sun 26 Sea Point, Tamboerskloof, Three Anchor Bay, Vredehoek, V & A Marina Accommodation Devilspeak, Zonnebloem, Fresnaye, Bakoven Truman and Orange Bergvliet, Diep River, Tokai, Meadowridge, Frogmore Estate, Southfield, Flintdale Estate, Plumstead, Constantia, Wynberg, Kirstenhof, Westlake, Steenberg Golf Estate, Constantia Village, Checkers Liquorshop Westlake Constantiaberg Bulletin 26 Silverhurst, Nova Constantia, Dreyersdal, Tussendal, John Collins Wines Kreupelbosch, Walloon Estate, Retreat, Orchard Village, Golf Links Estate Blouberg, Table View, Milnerton, Edgemead, Bothasig, Tygerhof, Sanddrift, Richwood, Blouberg Strand, Milnerton Ridge, Summer Greens, Melkbosstrand, Flamingo Vlei, TableTalk Duynefontein, -

Hout Bay and Llandudno Heritage Trust Meeting of Trustees Date : 16 April 2013 Venue : 6 Leeuloop Start Time : 16:30 – Klein Leeukop, Hout Bay End Time : 18:30

Hout Bay and Llandudno Heritage Trust Meeting of Trustees Date : 16 April 2013 Venue : 6 Leeuloop Start Time : 16:30 – Klein Leeukop, Hout Bay End Time : 18:30 Present Name Initials Deputy Chair Chris Everett CJE Treasurer Chris Hudson CH Members Dave Cowley DC Rodney Cronwright RC Jeremy Hele JH Keith Mackie KM Richard Timms RT Apologies Anne Murphy AM Neil van der Spuy NvdS Item Details Action 1 Welcome and apologies 1.1 The Vice-Chairman welcomed all members. 1.2 Attendance and apologies are as recorded above. 1.3 The meeting expressed its best wishes to the Chairman for a speedy return to full health 2 Minutes of Previous Meeting 2.1 The minutes of the previous meeting held on 04 February 2013 were approved. 3 Matters arising from Previous Minutes 3.1 Website Security settings for restricted access – Trustees / Gunners is still to be set up, DC with other modifications DC will investigate software to manage fundraising via the website. DC Membership application forms are available on the web-site TMNP – Conservation Plan - add or link it to HB&LHT Web-site DC 3.2 Gunners CJE / Harmonisation of HB Gunner’s training with that of CAOSA has not AD progressed. Cap squares on two carriages are missing KM Grommets on tompions to be replaced KM New G12 - “bulking up” has been investigated with AEL – strongly not AD / recommended due to both legal and safety reasons. Instead suggested that CJE smaller charges are used with powder set closer to the mouth of the cannon. Another consignment of Blasting Powder is on order by AEL – AD to follow up AD / CJE 3.3 Kronendal Development – International School - Environmental Monitoring KM Committee is in place. -

ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2013–MARCH 2014 Vision: the Creation of Sustainable Human Settlements Through Development Processes Which Enable Human Rights, Dignity and Equity

ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2013–MARCH 2014 Vision: The creation of sustainable human settlements through development processes which enable human rights, dignity and equity. Mission: To create, implement and support opportunities for community-centred settlement development and to advocate for and foster a pro-poor policy environment which addresses economic, social and spatial imbalances. Umzomhle (Nyanga), Mncediisi Masakhane, RR Section, Participatory Action Planning CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ANC African National Congress KCT Khayelitsha Community Trust BESG Built Environment Support Group KDF Khayelitsha Development Forum Abbreviations 2 BfW Brot für die Welt KHP Khayelitsha Housing Project CBO Community-Based Organisation KHSF Khayelitsha Human Settlements Our team 3 CLP Community Leadership Programme Forum Board of Directors 4 CoCT City of Cape Town (Metropolitan) LED Local economic development Chairperson’s report 5 CORC Community Organisation Resource LRC Legal Resources Centre Centre MIT Massachusetts Institute of Executive Director’s report 6 CBP Capacity-Building Programme Technology From vision to strategy 9 CPUT Cape Peninsula University of NDHS National Department of Human Technology Settlements Affordable housing and human settlements 15 CSO Civil Society Organisation NGO Non-Governmental Organisation Building capacity in the urban sector 20 CTP Cape Town Partnership NDP National Development Plan Partnerships 23 DA Democratic Alliance NUSP National Upgrading Support DAG Development Action Group Programme Institutional change 25 DPU -

AC097 FA Cape Town City Map.Indd

MAMRE 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 km PELLA ATLANTIS WITSAND R27 PHILADELPHIA R302 R304 KOEBERG R304 I CAME FOR DUYNEFONTEIN MAP R45 BEAUTIFULR312 M19 N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 LANDSCAPES,PAARL M14 R304 R302 R27 M58 AND I FOUND Blaauwberg BEAUTIFULN1 PEOPLE Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND M48 B6 ROBBEN ISLAND PARKLANDS R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE VIEW M13 JOOSTENBERG KILLARNEY DURBANVILLE VLAKTE City Centre GARDENS KRAAIFONTEIN N1 R44 Atlantic Seaboard Northern Suburbs SONSTRAAL M5 N7 Table Bay Sunset Beach R304 Peninsula R27 BOTHASIG KENRIDGE R101 M14 PLATTEKLOOF M15 Southern Suburbs M25 EDGEMEAD TYGER VALLEY MILNERTON SCOTTSDENE M16 M23 Cape Flats M8 BRACKENFELL Milnerton Lagoon N1 Mouille Point Granger Bay M5 Helderberg GREEN POINT ACACIA M25 BELLVILLE B6 WATERFRONT PARK GOODWOOD R304 Three Anchor Bay N1 R102 CAPE TOWN M7 PAROW M23 Northern Suburbs STADIUM PAARDEN KAYAMANDI SEA POINT EILAND R102 M12 MAITLAND RAVENSMEAD Blaauwberg Bantry Bay SALT RIVER M16 M16 ELSIESRIVIER CLIFTON OBSERVATORY M17 EPPING M10 City Centre KUILS RIVER STELLENBOSCH Clifton Bay LANGA INDUSTRIA M52 Cape Town Tourism RHODES R102 CAMPS BAY MEMORIAL BONTEHEUWEL MODDERDAM Visitor Information Centres MOWBRAY N2 R300 M62 B6 CABLE WAY ATHLONE BISHOP LAVIS M12 M12 M3 STADIUM CAPE TOWN TABLE MOUNTAIN M5 M22 INTERNATIONAL Police Station TABLE RONDEBOSCH ATHLONE AIRPORT BAKOVEN MOUNTAIN NATIONAL BELGRAVIA Koeël Bay PARK B6 NEWLANDS RYLANDS Hospital M4 CLAREMONT GUGULETU DELFT KIRSTENBOSCH M54 R310 Atlantic Seaboard BLUE DOWNS JAMESTOWN B6 Cape Town’s Big 6 M24 HANOVER NYANGA Oude Kraal KENILWORTH PARK -

Cape Town 2021 Touring

CAPE TOWN 2021 TOURING Go Your Way Touring 2 Pre-Booked Private Touring Peninsula Tour 3 Peninsula Tour with Sea Kayaking 13 Winelands Tour 4 Cape Canopy Tour 13 Hiking Table Mountain Park 14 Suggested Touring (Flexi) Connoisseur's Winelands 15 City, Table Mountain & Kirstenbosch 5 Cycling in the Winelands & visit to Franschhoek 15 Cultural Tour - Robben Island & Kayalicha Township 6 Fynbos Trail Tour 16 Jewish Cultural & Table Mountain 7 Robben Island Tour 16 Constantia Winelands 7 Cape Malay Cultural Cooking Experience 17 Grand Slam Peninsula & Winelands 8 “Cape Town Eats” City Walking Tour 17 West Coast Tour 8 Cultural Exploration with Uthando 18 Hermanus Tour 9 Cape Grace Art & Antique Tour 18 Shopping & Markets 9 Group Scheduled Tours Whale Watching & Shark Diving Tours Group Peninsula Tour 19 Dyer Island 'Big 5' Boat Ride incl. Whale Watching 10 Group Winelands Tour 19 Gansbaai Shark Diving Tour 11 Group City Tour 19 False Bay Shark Eco Charter 12 Touring with Families Family Peninsula Tour 20 Family Fun with Animals 20 Featured Specialist Guides 21 Cape Town Touring Trip Reports 24 1 GO YOUR WAY – FULL DAY OR HALF DAY We recommend our “Go Your Way” touring with a private guide and vehicle and then customizing your day using the suggested tour ideas. Cape Town is one of Africa’s most beautiful cities! Explore all that it offers with your own personalized adventure with amazing value that allows a day of touring to be more flexible. RATES FOR FULL DAY or HALF DAY– GO YOUR WAY Enjoy the use of a vehicle and guide either for a half day or a full day to take you where and when you want to go. -

City of Cape Town Profile

2 PROFILE: CITY OF CAPETOWN PROFILE: CITY OF CAPETOWN 3 Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction: Brief Overview ............................................................................. 8 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................................ 9 2.3 Spatial Status ....................................................................................................................... 11 3. Social Development Profile ............................................................................. 12 3.1 Key Social Demographics ..................................................................................................... 12 3.1.1 Population ............................................................................................................................ 12 3.1.2 Gender Age and Race ........................................................................................................... 13 3.1.3 Households ........................................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Health Profile ....................................................................................................................... 15 3.3 COVID-19 ............................................................................................................................ -

Approved Belcom Minutes 26 June 2013 Oz

APPROVED MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE, BUILT ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE PERMIT COMMITTEE (BELCom) Held on Wednesday, 26 June 2013, 1 st Floor Boardroom at the Offices of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport, Protea Assurance Building, Greenmarket Square, Cape Town at 09H00 1. Opening and Welcome The meeting was officially opened at 09H13 by the chairperson, Ms Sarah Winter, and she welcomed everyone present. 2. Attendance Members Members of Staff Ms Sarah Winter SW Ms Christina Jikelo CJ Dr Stephen Townsend ST Ms Lithalethu Mshoti (Sec) LM Ms Maureen Wolters MW Mr Calvin van Wijk CvW Mr Roger Joshua RJ Mr Ronny Nyuka RN Mr Trevor Thorold TT Mr Zwelibanzi Shiceka ZS Ms Melanie Attwell MA Mr Jonathan Windvogel JW Mr Patrick Fefeza PF Ms Ntombekhaya Nkoane NN Mr Tim Hart TM Mr Shaun Dyers SD Mr Olwethu Dlova (Sec) OD Visitors Mrs Claire Donovan CD Mr Henry Aikman HA Mr Frik Vermeulen FV Mr Raymond Morkel RM Mrs C Morkel CM Ms Lezanne Botha LB Mr John Powell JP Mrs Heidi Boise HB Mr Chris Snelling CS Mrs Robyn Berzen RB Observers None 3. Apologies Andrew Hall AH 4. Approval of minutes of previous meeting held 22 May 2013 4.1 The Committee resolved to approve the minutes with minor amendments. 5. Disclosure of Interest • TT, SW and MA: W.10.3 6. Approval of Agenda The Committee approved the agenda dated 26 June 2013 with a few additional amendments. 7. Confidential Matters 7.1 None Approved BELCom Minutes_26 June 2013 1 8. Administrative Matters 8.1 Outcome of the Appeals and Tribunal Committees Mr van Wijk gave a report back on the outcomes of the following appeals matter: • Proposed Adjustments to Dairy Parlour, Vergelegen Estate, Lourensford Road, Somerset West. -

Municipality of the City of Cape Town: Zoning Scheme : Scheme Regulations

MUNICIPALITY OF THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN: ZONING SCHEME: SCHEME REGULATIONS March 1993 MUNICIPALITY OF THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN: ZONING SCHEME : SCHEME REGULATIONS These Scheme Regulations are approved in terms of Section 9(2) of the Land Use Planning Ordinance (No 15 of 1985) by the powers vested in the Administrator and as published in Provincial Gazette No 4649 dated 29 June 1990 and further corrected by virtue of publication in Provincial Gazette No 4684 dated 1 March 1991. 3 (i) CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTORY Section 1 Scheme Regulations 2 Definitions 3 Notations on Map 4 Land Not Represented on the Map 5 Conflict of Laws 6 Evasion of Intent of Scheme 7 Area of Scheme 8 Method of measuring distances etc. 9 Buildings requiring Council's consent: advertising 10 Buildings requiring Council's consent: applicable restrictions CHAPTER II: USE ZONING Section 11 Use zones and sub-zones 12 Public Open Spaces 13 Streets, New Streets, Street Widenings, Improvements or Closures 14 Classification of buildings 15 Permitted uses of land and buildings 16 Special Buildings 17 Restrictions on Special Buildings, buildings in Community Facilities and Show and Exhibition Use Zones and Use Zones referred to in section 15(5) 18 Prohibited uses of land and buildings 19 Combined Building or more than one building on a site 20 Outbuildings 21 Building in more than one Use Zone 22 Subsidiary uses: when permitted 23 Timber yards, coal yards, etc. 24 Use of land for parking purposes 25 Letting of rooms in Dwelling Units 26 Certain buildings or uses prohibited CHAPTER III: -

5685 Horizon Capital the Azure

STREET VIEW – SET AGAINST A MAJESTIC BACKDROP Nestled between the mountains and the sea A blend of luxury and quiet sophistication Welcome to The Azure: an exclusive residential development nestled between Lion’s Head, the Twelve Apostles and Camps Bay beach. Located in the village at the heart of Camps Bay, one of Cape Town’s most desirable neighbourhoods, The Azure comprises four landmark residences designed to the highest standards, within a short walk to the beach. Sophisticated and relaxed, contemporary yet timeless, each residence accentuates the beauty of its natural surroundings. With Lion’s Head rising to the north, The Azure is backed by the majestic Twelve Apostles mountains and looks towards the Atlantic Ocean – the perfect setting at the tip of Africa. THE AZURE / 1 RESIDENCE 4 – MASTER BATHROOM – TRANQUILLITY MEETS STYLE 2 / THE AZURE RESIDENCE 4 – KITCHEN – LUXURIOUSLY FINISHED, ERGONOMICALLY DESIGNED The perfect setting for welcoming friends and family THE AZURE / 3 RESIDENCE 3 – MASTER-SUITE - BEAUTIFUL VIEWS AND FRESH OCEAN AIR 4 / THE AZURE The master bedroom embodies the sense of luxury and privacy that defines The Azure THE AZURE / 5 RESIDENCE 3 – TERRACE – SEAMLESS INDOOR AND OUTDOOR LIVING Designed for open-plan living and easy entertaining 6 / THE AZURE THE AZURE / 7 RESIDENCE 3 – LOUNGE – OPEN-PLAN LIVING Sophisticated living with the space and freedom to breathe the ocean air 8 / THE AZURE THE AZURE / 9 RESIDENCE 4 – LOUNGE – AN OPEN SPACE WITH PICTURESQUE VIEWS Natural stone and timber creates a warm and tranquil