Emergency on Planet Cape Town?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

Rainy Day in Cape Town!

Parker Cottage’s Suggestions for a Rainy Day in Cape Town! Yes, it’s true. It even rains in Cape Town! When it does, there are actually quite a few fun things you can do. No need to bury your head under the duvet and hibernate: get out there! Parker Cottage Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za The Two Oceans Aquarium … Whilst it’s not enormous, our aquarium is one of the nicest ones I’ve ever visited because of the interesting way it’s laid out. There is a shark tank, pressurized tanks for ultra-deep sea creatures and also a kelp forest tank (my favourite) complete with wave machine where you can watch the fish swimming inside an underwater forest. Check out the daily penguin and shark-tank feedings to see our beautiful creatures in hungry action, or visit the touch-pool for an interactive experience. The staff are also really fun and the place is well maintained and clean. Dig deep to find your inner child and you’ll enjoy. Open every day from 09h30 – 18h00. Shark feedings on Sundays at 15h00, and penguin feedings daily at 11h45 and 14h30. Parker Cottage Tel +27 (21)424-6445 | Fax +27 (0)21 424-0195 | Cell +27 (0)79 980 1113 1 & 3 Carstens Street, Tamboerskloof, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] | www.parkercottage.co.za Indoor markets … Cape Town is no stranger to the concept of the market and the pop-up shop. -

Final Belcom Agenda 18 April 2012

MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE BELCOM 18 APRIL 2012, IN THE 1st FLOOR BOARDROOM, PROTEA ASSURANCE BUILDING, GREENMARKERT SQUARE, CAPE TOWN AT 08H00 PLEASE NOTE THAT: LUNCH TIME WILL START AT 12H30 UNTIL 14H30 DUE TO UNVEILING OF HWC BADGES Case Item Case No Subject Documents to be tabled Matter Reference Officer Documents sent to Notes 1 Opening 2 Attendance 3 Apologies 4 Approval of the previous minutes 4.1 Meeting held on 22 March 2012 4.2 Meeting held on 30 March 2012 5 Confidential Matters 6 Administration Matters Outcome of the Appeals and Tribunal AH/CvW 6.1 Committees ZS 6.2 Erf 443, 47 Napier Street, De Waterkant 7 Appointments None 7.1 MATTERS TO BE DISCUSSED FIRST SESSION: TEAM WEST PRESENTATION W.8 PROVINCIAL HERITAGE SITE: SECTION 27 PERMIT APPLICATIONS Proposed Re-Assembly of the Cenotaph on A Heritage Statement prepared by Bridget Matter W.8.1 HM/CAPE TOWN/GRAND PARADE JW the Grand Parade, Darling Street, Cape Town O'Donoghue, dated April 2012 to be tabled. Arising Site Inspection Report prepared by Mr Chris W.8.2 Proposed Routine Road and Stone Retaining Wall Maintanance, Swartberg Pass, Main Snelling to be tabled Matter HM/CANGO CAVES TO PRINCE Road 369, from Cango caves to Prince Albert Arising ALBERT RN X1110601TG0 Proposed Alterations and Additions, South Matter W.8.3 Re-Submission to be tabled HM/NEWLANDS/ERF 96660 TG 3 African Breweries, Erf 96660, Newlands Arising BELCom Agenda 18 April 2012 Page 1 HM/TULBAGH/SCHOONDERZICHT W.8.4 TG SW, MA and RJ Proposed Alterations and Additions, Farm A Heritage Statement prepared -

The Ultimate Digital Nomad Guide

THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL NOMAD GUIDE CAPE TOWN 2020 CAPE TOWN - NEW DIGITAL NOMAD HOTSPOT Cape Town has become an attractive destination for digital nomads, looking to venture to an African city and explore the local cultures and diverse wildlife. Cape Town has also become known as Africa’s largest tech hub and is bustling with young startups and small businesses. Cape Town is definitely South Africa’s trendiest city with hipster bars and restaurants along Bree street, exclusive beach strips with five star cuisine and rolling vineyards and wine farms. But is Cape Town a good city for digital nomads. We will dive into this and look at accommodation, co-working spaces, internet connectivity,safety and more. Let's jump into a guide to living and working as a digital nomad in Cape Town, written by digital nomads, from Cape Town. VISA There are 48 countries that do not need a visa to enter South Africa and are abe to stay in SA as a visitor for 90 days. See whether your country makes this list here. The next group of countries are allowed in for 30 days visa-free. Check here to see if your country is on this list. If your country does not fall within these two categories, you will need to apply for a visa. If you can enter on a 90 day visa you can extend it for another 90 days allowing you to stay in South Africa for a total of 6 months. You will need to do this 60 days prior to your visa end date. -

Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930 Robert Edgar

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Articles Faculty Publications 12-15-2016 "The oM st Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:" Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930 Robert Edgar Myra Ann Howser Ouachita Baptist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles Part of the African History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Edgar, Robert and Howser, Myra Ann, ""The osM t Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:" Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930" (2016). Articles. 87. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Most Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:” Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leadership, 1930 Abstract: Former South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts’ 1930 European and North American tour included a series of interactions with diasporic African and African American activists and intelligentsia. Among Smuts’s many remarks stands a particular speech he delivered in New York City, when he called Africans “the most patient of all animals, next to the ass.” Naturally, this and other comments touched off a firestorm of controversy surrounding Smuts, his visit, and segregationist South Africa’s laws. Utilizing news coverage, correspondence, and recollections of the trip, this article uses his visit as a lens into both African American relations with Africa and white American foundation work towards the continent and, especially, South Africa. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

CT, Franschoek, Eastern Cape

T H E A F R I C A H U B S O U T H B Y S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G A F R I C A T r u s t e d i n s i d e r k n o w l e d g e f r o m h a n d p i c k e d e x p e r t s S A M P L E I T I N E R A R Y # 1 I N P A R T N E R S H I P W I T H N E W F R O N T I E R S T O U R S Cape Town, Franschoek "South Africa can be overwhelming to sell due & Eastern Cape Safari to the sheer variety of locations and 9 nights accommodation options. This SA information sharing partnership between SWM and New Frontiers is invaluable in helping to inform & enthuse aficionados and non-specialists alike." - Albee Yeend, Albee's Africa W W W . S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G . C O . U K / T H E A F R I C A H U B I T I N E R A R Y W H O ? O V E R V I E W Families | Couples H I G H L I G H T S 4 nights | Cape Grace Cape Grace offers an excellent location to 2 nights | Boschendal explore the city from 3 nights | Kwandwe Great Fish River Lodge Treehouse experience included in Boschendal stay Guests will spend their first 4 nights Exceptional game viewing experience in the discovering Cape Town. -

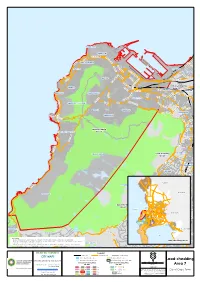

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

Informal Settlement Upgrading in Cape Town’S Hangberg: Local Government, Urban Governance and the ‘Right to the City’

Informal Settlement Upgrading in Cape Town’s Hangberg: Local Government, Urban Governance and the ‘Right to the City’ by Walter Vincent Patrick Fieuw Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sustainable Development Planning and Management in the Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Firoz Khan December 2011 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature Walter Fieuw Name in full 22/11/2011 Date Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Integrating the poor into the fibre of the city is an important theme in housing and urban policies in post‐apartheid South Africa. In other words, the need for making place for the ‘black’ majority in urban spaces previously reserved for ‘whites’ is premised on notions of equity and social change in a democratic political dispensation. However, these potentially transformative thrusts have been eclipsed by more conservative, neoliberal developmental trajectories. Failure to transform apartheid spatialities has worsened income distribution, intensified suburban sprawl, and increased the daily livelihood costs of the poor. After a decade of unintended consequences, new policy directives on informal settlements were initiated through Breaking New Ground (DoH 2004b). -

Greater Cape Metro Regional Spatial Implementation Framework Final Report July 2019

Greater Cape Metro Regional Spatial Implementation Framework Final Report July 2019 FOREWORD The Western Cape Government will advance the spatial transformation of our region competitive advantages (essentially tourism, food and calls on us all to give effect to a towards greater resilience and spatial justice. beverages, and education) while anticipating impacts of technological innovation, climate change and spatial transformation agenda The Department was challenged to explore the urbanization. Time will reveal the extent to which the which brings us closer to the linkages between planning and implementation dynamic milieu of demographic change, IT advances, imperatives of growing and and to develop a Greater Cape Metropolitan the possibility of autonomous electric vehicles and sharing economic opportunities Regional Implementation Framework (GCM RSIF) climate change (to name a few) will affect urban and wherever we are able to impact rather than “just another plan” which will gravitate to regional morphology. The dynamic environment we upon levers of change. Against the bookshelf and not act as a real catalyst for the find ourselves in is underscored by numerous potential the background of changed implementation of a regional logic. planning legislation, and greater unanticipated impacts. Even as I pen this preface, clarity regarding the mandates of agencies of This GCM RSIF is the first regional plan to be approved there are significant issues just beyond the horizon governance operating at different scales, the PSDF in terms of the Western Cape Land Use Planning Act, for this Province which include scientific advances in 2014 remained a consistent guide and mainspring, 2014. As such it offered the drafters an opportunity (a AI, alternative fuel types for transportation (electric prompting us to give urgent attention to planning in kind of “laboratory”) to test processes and procedures vehicles and hydrogen power) and the possibility the Greater Cape Metropolitan Region as one of three in the legislation. -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus