The Mortal Instruments and Freeform’S Shadowhunters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Simon's Heroic Journey in Cassandra Clare's The

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.3 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed Journal 2016 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE SIMON’S HEROIC JOURNEY IN CASSANDRA CLARE’S THE MORTAL INSTRUMENTS *1 2 G. Sharmely , Dr. V. Chanthiramathi 1* (Ph. D Research Scholar , PG & Research Department of English V.O. Chidambaram College, Thoothukudi – 8) 2(Associate Professor of English, PG & Research Department of English V.O. Chidambaram College, Thoothukudi – 8) ABSTRACT In recent young adult urban fantasy literature, the heroic character and the heroic journey have become one of the most important elements, as supernatural and futuristic elements allow exploration of all kinds of traits and decisions that create the idealized state which heroes represent. Frequently, the protagonist is unwilling to be a champion, or is of low or timid origin. Though events are mostly beyond their control, the protagonists are thrust into points of huge importance where their caliber is proved in a number of divine and physical challenges. The several tasks presented throughout the hero’s journey transform the characters into heroes. Simon, one of the protagonists of The Mortal Instruments is originally introduced as a mundane to the Shadow World. My paper explores Simon’s heroic journey from a mundane to a vampire and then later to a Daylighter. Though in the end of the novel series, Simon’s immortality was taken away, along with his memories by making him into a mundane again, the author Cassandra Clare shows Simon’s gradual journey of becoming a hero throughout the series. Keywords: Young adult literature, Urban fantasy, Heroic journey, Shadow hunters, Vampires. -

Lady Midnight Online Ebook by Cassandra Clare

Lady Midnight Online eBook by Cassandra Clare Book details: Author: Cassandra Clare Format: 688 pages Dimensions: 130 x 198mm Publication date: 23 Feb 2017 Publisher: Simon & Schuster Ltd Imprint: Simon & Schuster Childrens Books Release location: London, United Kingdom Synopsis: The Shadowhunters of Los Angeles star in the first novel in Cassandra Clare's newest series, The Dark Artifices, a sequel to the internationally bestselling Mortal Instruments series. Lady Midnight is a Shadowhunters novel. It's been five years since the events of City of Heavenly Fire that brought the Shadowhunters to the brink of oblivion. Emma Carstairs is no longer a child in mourning, but a young woman bent on discovering what killed her parents and avenging her losses. Together with her parabatai Julian Blackthorn, Emma must learn to trust her head and her heart as she investigates a demonic plot that stretches across Los Angeles, from the Sunset Strip to the enchanted sea that pounds the beaches of Santa Monica. If only her heart didn't lead her in treacherous directions...Making things even more complicated, Julian's brother Mark-who was captured by the faeries five years ago-has been returned as a bargaining chip. The faeries are desperate to find out who is murdering their kind-and they need the Shadowhunters' help to do it. But time works differently in faerie, so Mark has barely aged and doesn't recognize his family. Can he ever truly return to them?Will the faeries really allow it? Glitz, glamours, and Shadowhunters abound in this heartrending opening to Cassandra Clare's Dark Artifices series. -

The Heroic Journey of Tessa Gray in Cassandra Clare's the Infernal Devices

International Journal of Linguistics and Literature (IJLL) ISSN(P): 2319-3956; ISSN(E): 2319-3964 Vol. 5, Issue 5, Aug - Sep 2016; 39-44 © IASET THE HEROIC JOURNEY OF TESSA GRAY IN CASSANDRA CLARE’S THE INFERNAL DEVICES G. SHARMELY Ph. D Research Scholar, P.G & Research, Department of English, V.O. Chidambaram College, Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu, India ABSTRACT Fantasy is a genre where heroes can show off their skills and earn respect through feats such as defeating dragons, reaching their destinations unscathed while being hunted by armies, and solving prophecies that tell how the enemy can be defeated. The heroine stands between several roles, that of a special person who has the power to defeat dark forces and as a fighter who trusts only herself. Modern heroines are warriors who fight on their own. Cassandra Clare, a famous fantasy writer worked for several years as an entertainment journalist for the Hollywood Reporter before turning her attention to fiction. This article attempts to explore the heroine’s journey of the protagonist Tessa Gray in Cassandra Clare’s The Infernal Devices . KEYWORDS: Chosen One, Fantasy, Heroic Journey, Monomyth, Shadowhunters, Steampunk Novel, The Infernal Devices, Young Adult INTRODUCTION The heroic character has become one of the most important elements, as supernatural and futuristic elements allow exploration of all kinds of traits and decisions that create the idealized state which heroes represent. The several tasks presented throughout the hero’s journey transform the characters into heroes. Heroine’s journeys are also common in fantasy, produced mainly in fairytales rather than in the longer epics. -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee Nashville Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE NASHVILLE DIVISION SHERRILYN KENYON, ) ) Plaintiff, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 3:16-cv-0191 ) Chief Judge Sharp CASSANDRA CLARE, a/k/a JUDITH ) Magistrate Judge Knowles RUMELT, a/k/a JUDITH LEWIS ) ) and ) ) DOES 1 through 50, inclusive, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS Defendant Cassandra Clare (“Defendant” or “Clare”) respectfully submits this memorandum in support of her motion, pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(2) and 12(b)(6), to dismiss the Complaint of Plaintiff Sherrilyn Kenyon (“Plaintiff” or “Kenyon”) (ECF Doc. No 1) in its entirety. I. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT This lawsuit is another example of an unfortunate and all-too-common blight on the creative fields: a successful author (or songwriter, film producer, etc.) is sued by a disgruntled would-be competitor on trumped-up claims for the purpose of cashing in on the success of that author. Tens of millions of Clare’s books—fantasy derived principally by the Judeo-Christian narrative (e.g., young heroes who are the progeny of angels) aimed at teenagers and young adults—have been sold over a decade and been turned into a major motion picture, titled The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones (the “Movie”) and a television series, titled Shadowhunters: The Mortal Instruments (the “Television Series”). Kenyon, who has been in print since the {01378372.2 } Case 3:16-cv-00191 Document 18 Filed 04/25/16 Page 1 of 26 PageID #: 112 1990’s and first enjoyed some success (albeit not of the magnitude of Clare) with self-described “sexy” adult novels featuring adult heroes drawn from Greek mythology who engage in explicitly adult activities.1 Aware of Clare’s use of the term “Shadowhunters” since at least 2007, Kenyon admittedly did not allege that Clare had infringed on her “Dark-Hunter” adult book series before bringing suit in February 2016. -

Cassandra Clare Q&A

Q&A Contact: Rhalee Hughes rhalee hughes public relations + marketing 212.260.2244 [email protected] CASSANDRA CLARE Q&A LADY MIDNIGHT: BOOK ONE THE DARK ARTIFICES, A Shadowhunters Novel by Cassandra Clare; McElderry/ S&S; Hardcover Fiction; $24.99;On Sale March 8, 2016; 720 pages; Ages 14 and up; ISBN: 9781442468351 Q: Lady Midnight is a Shadowhunters novel, however it is also book one in a new series: The Dark Artifices. Can someone who has not read previous Shadowhunter books start with Lady Midnight? Cassandra Clare: Absolutely. I think of it as like Star Wars: The Force Awakens. If you’ve seen the previous Star Wars movies, it helps, and you’ll be happy to see familiar characters again. If not, then the film works just fine as a great adventure movie on its own and those characters are introduced with enough backstory to explain who they are. And the focus is on the new cast, that everyone will be getting to know in Lady Midnight. Q: Fans of your books are chomping at the bit for Lady Midnight. Can you share five things that they should look forward to in advance of grabbing a copy on March 8th? CC: 1) The solution to long-running mysteries like why you can’t fall in love with your parabatai, your warrior partner. 2) A fun new heroine in Emma, who is a bit reckless and driven by a desire for revenge. 3) A whole bunch of new characters to know and love, including the huge Blackthorn family, who are like all great families, big and messy and loving and would die for each other. -

Clockwork PRINCESS CASSANDRA CLARE the INFERNAL DEVICES

Clockwork PRINCESS CASSANDRA CLARE THE INFERNAL DEVICES BOOK THREE READING GROUP GUIDE About This Book Great things are afoot at the London Institute. Tessa and Jem are preparing for their wedding. Charlotte and Henry are expecting a baby. Cecily Herondale and Gideon Lightwood have joined the Institute’s ranks. Jessamine is coming home. And no longer believing himself to be cursed, Will can finally open his heart to love. But despite the causes for celebration, everyone is weighed down by a sense of pervasive gloom. Mortmain is still out there somewhere, biding his time before he strikes again, Consul Wayland is undermining Charlotte’s leadership, and Tessa knows that her happiness with Jem comes with a price—Will’s heart. When Mortmain’s clockwork automatons attack the Institute, leaving behind injury and confusion and death, the Shadowhunters must fight for everything they’ve ever believed in or held dear. Tessa and her friends must find Mortmain and stop him, or risk losing Jem, the Institute, their lives…and even the world as they know it. Discussion Questions 1. Cassandra Clare begins the book with a stanza from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “In Memoriam A.H.H.” What is this poem about? In what ways does the overarching message of this poem fit with the events and themes of lockworkC Princess? 2. When Jem and Will first meet as boys of twelve, Jem tells Will not to “be ordinary like that. Don’t say you’re sorry.” Is either boy ordinary? What is it about their circumstances that allow them to connect with each other? Does their relationship change over the years? 3. -

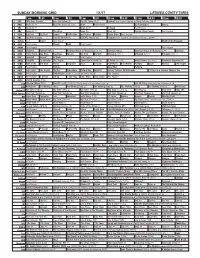

Sunday Morning Grid 1/1/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/1/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football New England Patriots at Miami Dolphins. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Program Oz Reimagined Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Florida Citrus Parade Paid Program 9 KCAL Big Deal Big Deal People CHiP’s-Kids Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program March of the Penguins 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Downton Downton Abbey Downton Abbey on Masterpiece (8:37) Downton Abbey Downton Abbey on Masterpiece Å Downton 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Artbound (TVY) Å Artbound (TVY) Å Artbound (TVY) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Paid Program 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Zona NBA Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl Forever Painless With Miranda 21 Days to a Slimmer Younger You 52 KVEA Paid Program Fútbol Inglés Arsenal FC vs Crystal Palace FC. -

'Shadowhunters' Helps Launch Freeform

CELEBRITY SPOTLIGHTS JENNIFER LOPEZ NICOLE SULLIVAN CHRISTINA ROLLYSON TIM DEKAY THE STORY! SHAUN T ‘Shadowhunters’ helps launch Freeform WHAT'S FOR Katherine McNamara stars in DINNER “Shadowhunters,” premiering Featuring: Tuesday as ABC Family turns into Freeform. “Cake Wars” FEATURED STORIES “COLONY” EXCLUSIVE! “SESAME STREET” “GALAVANT” PROFILED ATHLETE MOVIES TO WATCH PATRICK KANE And so much more! Connect to these shows within this magazine! FOLIO Courtesy of Gracenote January 10 - 16, 2016 C What’s HOT this Week! Click to jump to these contents featured sections! YOURTVLINK CELEBRITY “COLONY” 4 JENNIFER LOPEZ USA Network series puts Her “Shades of Blue” Los Angeles under siege considers how “we get messy” 5 NICOLE SULLIVAN “MADtv” reunion has its heart “in the right place” 6 CHRISTINA ROLLYSON Lookin’ for love 8 TIM DEKAY DeKay didn’t let Michael York down “SESAME STREET” 9 SHAUN T What’s new on the ‘Street’ ABC’s newest weight loss show fits him to a T “GALAVANT” FOOD Laughing while they work 7 “CAKE WARS” 17 May the ‘Cake’ force be with you SPORTS 18-19 PATRICK KANE and the Chicago THE STORY! Blackhawks eye another “SHADOWHUNTERS” postseason run. Supernatural adventure helps give Freeform its start REALITY 16 THE 73RD ANNUAL GOLDEN GLOBE AWARDS MOVIES IN EVERY ISSUE Jamie Foxx is “super- 20-21 Featuring: Theatrical 22-23 Featuring: Our top proud” of award- Review, Our top DVD pick, suggested programs to watch presenting daughter and Coming Soon on DVD. this week! Corinne. Page 2 YOUR TV LINK Courtesy of Gracenote January 10 - 16, 2016 Editor's choice STORY S ABC Family becomes Freeform with help from ‘Shadowhunters’ BY JAY BOBBIN on the air currently – says he’s “thrilled to be a part” of the A lot is riding on “Shadowhunters”: Not only does it turn a Freeform repositioning “right at the ‘go’ moment. -

The Future Is Female

WINTER 2018 WE SET OUT TO FIND CANADA’S MOST IMPRESSIVE YOUNG PRODUCERS AND DISCOVERED THE FUTURE IS FEMALE PAW PATROL-ING THE WORLD OVER THE TOP? How Spin Master found the right balance We ask Netflix for their of story, product and marketing to create take on the public reaction a global juggernaut to #CreativeCanada 2 LETTER FROM THE CEO TABLE OF 3 LETTER FROM THE CMPA ADDRESSING HARASSMENT WITHIN CONTENTS CANADA’S PRODUCTION SECTOR 12 OVER THE TOP? A CONVERSATION WITH NETFLIX CANADA’S CORIE WRIGHT 4 18 S’EH WHAT? THE NEXT WAVE A LEXICON OF CANADIANISMS FROM YOUR FAVOURITE SHOWS CHECK OUT SOME OF THE BEST AND BRIGHTEST WE GIVE OF CANADA’S EMERGING CREATOR CLASS 20 DON’T CALL IT A REBOOT MICHAEL HEFFERON, RAINMAKER ENTERTAINMENT 22 TRAILBLAZERS CANADA’S INDIE TWO ALUMNI OF THE CMPA MENTORSHIP PROGRAM RISE HIGHER AND HIGHER 24 IN FINE FORMAT PRODUCERS MARIA ARMSTRONG, BIG COAT MEDIA 28 HOSERS TAKE THE WORLD THE TOOLS MARK MONTEFIORE, NEW METRIC MEDIA THEY NEED PRODUCTION LISTS so they can bring 6 30 DRAMA SERIES 44 COMEDY SERIES THE FUTURE IS FEMALE diverse stories to 55 CHILDREN’S AND YOUTH SERIES MEET NINE OF CANADA’S BARRIER-TOPPLING, STEREOTYPE-SMASHING, UP-AND-COMING PRODUCERS 71 DOCUMENTARY SERIES life on screen for 84 UNSCRIPTED SERIES 95 FOREIGN LOCATION SERIES audiences at home and around the world 14 WINTER 2018 THE CMPA A FEW GOOD PUPS HOW SPIN MASTER ENTERTAINMENT ADVOCATES with government on behalf of the industry TURNED PAW PATROL INTO AN PRESIDENT AND CEO: Reynolds Mastin NEGOTIATES with unions and guilds, broadcasters and funders UNSTOPPABLE SUPERBRAND OPENS doors to international markets CREATES professional development opportunities EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Andrew Addison CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Kyle O’Byrne SECURES exclusive rates for industry events and conferences 26 CONTRIBUTOR AND COPY EDITOR: Lisa Svadjian THAT OLD EDITORIAL ASSISTANT: Kathleen McGouran FAMILIAR FEELING CONTRIBUTING WRITER: Martha Chomyn EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN! DESIGN AND LAYOUT: FleishmanHillard HighRoad JOIN US. -

The Wicked Ones by Cassandra Clare and Robin Wasserman 7

GHOSTS OF THE SHADOW MARKET BOOK 6 THE WICKED ONES by CASSANDRA CLARE and ROBIN WASSERMAN Shadow Market Enterprises, Inc. Amherst, MA · Los Angeles, CA Ghosts of the Shadow Market 1. Son of the Dawn by Cassandra Clare and Sarah Rees Brennan 2. Cast Long Shadows by Cassandra Clare and Sarah Rees Brennan 3. Every Exquisite Thing by Cassandra Clare and Maureen Johnson 4. Learn About Loss by Cassandra Clare and Kelly Link 5. A Deeper Love by Cassandra Clare and Maureen Johnson 6. The Wicked Ones by Cassandra Clare and Robin Wasserman 7. The Land I Lost by Cassandra Clare and Sarah Rees Brennan 8. Through Blood, Through Fire by Cassandra Clare and Robin Wasserman The Shadowhunter Chronicles The Mortal Instruments City of Bones City of Ashes City of Glass City of Fallen Angels City of Lost Souls City of Heavenly Fire The Infernal Devices Clockwork Angel Clockwork Prince Clockwork Princess The Dark Artifices Lady Midnight Lord of Shadows Queen of Air and Darkness (forthcoming) The Eldest Curses (with Wesley Chu; forthcoming) The Red Scrolls of Magic The Lost Book of the White The Eldest Curses 3 The Last Hours (forthcoming) Chain of Gold Chain of Iron The Last Hours 3 The Shadowhunter’s Codex (with Joshua Lewis) The Bane Chronicles (with Sarah Rees Brennan & Maureen Johnson) Tales From the Shadowhunter Academy (with Sarah Rees Brennan, Maureen Johnson & Robin Wasserman) A History of Notable Shadowhunters and Denizens of Downworld (illustrated by Cassandra Jean) Also by Cassandra Clare The Magisterium Series (written with Holly Black) The Iron Trial The Copper Gauntlet The Bronze Key The Silver Mask The Golden Tower (forthcoming) This is a work of fiction. -

130Mm Tv Time Fans Cast Their Vote on the State of Diversity on Television

1 130MM TV TIME FANS CAST THEIR VOTE ON THE STATE OF DIVERSITY ON TELEVISION Television viewers are overwhelmingly voicing their desire for shows with diverse and strong characters. TV Time conducted this study to better understand how television audiences are responding to casting decisions across race, gender and sexual orientation. Gone are the days when our favorite characters were predominantly white, straight and male. A super- charged social consciousness is driving people to want to see characters on television who resemble themselves. Television is answering that call to action and fans are responding in overwhelming favor. TV Time is uniquely poised with volumes of fan data from people who have watched a television program and voted on their favorite characters in the TV Time app. For this global study, TV Time analyzed the top 100 favorite characters from 2015-2017, chosen by its community of 12 million registered app users. In an eff ort to understand how fans are reacting to diversity characters, TV Time tabulated 130 million character votes over the last three years. Acknowledging that there are several ways to segment the US population (and television characters) into diversity groups, this study focused on gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation. Overall, diversity among favorite characters remains relatively fl at over the past three years. However, some diversity groups are experiencing meaningful growth and appear to be leading the cultural movement toward embracing fundamental changes in the way we experience television. Published on April 23, 2018 2 CHARACTERS OF COLOR Overall, characters of color saw a 20% increase, jumping from 15% of the overall favorite characters in 2015, to 18% of the favorite character vote in 2017.