Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Program Features Don Byron's Spin for Violin and Piano Commissioned by the Mckim Fund in the Library of Congress

Concert on LOCation The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress "" .f~~°<\f /f"^ TI—IT A TT^v rir^'irnr "ir i I O M QUARTET URI CAINE TRIO Saturday, April 24, 2010 Saturday, May 8, 2010 Saturday, May 22, 2010 8 o'clock in the evening Atlas Performing Arts Center 1333 H Street, NE In 1925 ELIZABETH SPRAGUE COOLIDGE established the foundation bearing her name in the Library of Congress for the promotion and advancement of chamber music through commissions, public concerts, and festivals; to purchase music manuscripts; and to support musical scholarship. With an additional gift, Mrs. Coolidge financed the construction of the Coolidge Auditorium which has become world famous for its magnificent acoustics and for the caliber of artists and ensembles who have played there. The McKiM FUND in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson, to support the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. The audiovisual recording equipment in the Coolidge Auditorium was endowed in part by the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress. Request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 [email protected]. Due to the Library's security procedures, patrons are strongly urged to arrive thirty min- utes before the start of the concert. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the chamber music con- certs. -

Preview No Exit Plans Two Concerts Celebrating the Life and Work of Raymond Scott by Mike Telin “Like Most of Us, As a Kid I Watched the Warner Broth- Ers Cartoons

Preview No Exit plans two concerts celebrating the life and work of Raymond Scott by Mike Telin “Like most of us, as a kid I watched the Warner Broth- ers cartoons. Of course I didn't know that was his mu- sic,” says No Exit new music ensemble artistic direc- tor, Timothy Beyer. “But when as a teenager I heard the proper jazz versions of these pieces I remember thinking, I’ve heard that before!” Whose music is Beyer speaking of? The one and only Raymond Scott. On Friday, November 15 at Spaces Gallery and Mon- day, November 18 in Drinko Hall at Cleveland State !1,9(56,7<2;,7%(*,167+(,5B)7+6($621:,7+$ celebration of the life and work of the great Raymond Scott. The concerts feature new arrangements of some of Scott's most recognizable works by Geoffrey Burleson (Powerhouse Passacaglia), Russ Gershon (Snake Woman & Song of India), Greg DʼAlessio (War Dance for Wooden Indi- ans), Christopher Auerbach-Brown (The Man at the Typewriter) and Eric Gonzalez (Cel- ebration On the Planet Mars). The concerts also feature new compositions inspired by Scott’s music by James Praznik (Turkey in Twilight) and Timothy Beyer (Egyptian Barn Dance Meditation). Timothy Beyer says that “Scott was a truly brilliant guy whose genius couldnʼt be con- tained within a single medium. For instance, he was one of the early pioneers of elec- tronic music — some of which will be featured on the program along with pieces inspired by his Quintette — and he developed many early devices for composing and creating electronic works. -

International Computer Music Conference (ICMC/SMC)

Conference Program 40th International Computer Music Conference joint with the 11th Sound and Music Computing conference Music Technology Meets Philosophy: From digital echos to virtual ethos ICMC | SMC |2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece ICMC|SMC|2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece Programme of the ICMC | SMC | 2014 Conference 40th International Computer Music Conference joint with the 11th Sound and Music Computing conference Editor: Kostas Moschos PuBlished By: x The National anD KapoDistrian University of Athens Music Department anD Department of Informatics & Telecommunications Panepistimioupolis, Ilissia, GR-15784, Athens, Greece x The Institute for Research on Music & Acoustics http://www.iema.gr/ ADrianou 105, GR-10558, Athens, Greece IEMA ISBN: 978-960-7313-25-6 UOA ISBN: 978-960-466-133-6 Ξ^ĞƉƚĞŵďĞƌϮϬϭϰʹ All copyrights reserved 2 ICMC|SMC|2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sponsors ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Preface ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Summer School ....................................................................................................................................... -

Wild Bill Davis

BULLETIN NR 1, FEBRUARI 2019, ÅRGÅNG 27 Wild Bill Davis Duke’s Organ Grinder I detta nummer – In this issue Ledare 2 Monsignor John Sanders Cootie Williams i ord, bild och ton 2 in memoriam 13 Wild Bill Davis – A real gone organist 4 Harlem Air Shaft 14 Wild Bill Davis Biography 7 Bensonality och Jam With Sam 17 Wild Bill Davis (by Steve Voce) 9 Duke Ellingtons textförfattare 18 Johnny Hodges interviewed 10 Kallelse 20 1-2019 Gott Nytt År! Nu går vi in i ett nytt DESS-år. Det 25:e I min ledare i vår förra Bulletin gick I sammanhanget är det intressant att året i DESS verksamhet. Kanske värt att jag ut med ett upprop och efterlyste notera att procenten utländska medlem- celebrera vid något tillfälle under året. medlemmar som kunde tänka sig att på mar sakta ökar. Anledningen torde vare Vår första Bulletin kom ut hösten 1994 något sätt delta i styrelsens arbete. An- att dessa medlemmar finner Bulletinens och har sedan rullat på. I början bestod tingen som formell styrelseledamot eller engelskspråkiga artiklar intressanta och medlemstidningen av enbart 12 sidor. adjungerad dylik. Dessvärre har ingen läsvärda och motiverar medlemsavgif- 2010 ökade sidantalet till 16 sidor och i hört av sig. Det är tråkigt. Vi kan behöva ten. och med sista numret 2012 ökades sidan- nytt blod och nya idéer i styrelsen, men Avslutningsvis vill jag hälsa alla talet till 20. Även om det funnits material nu får vi tydligen rulla på i de gamla medlemmar välkomna till årsmötet den tillgängligt för att fylla fler än 20 sidor hjulspåren. -

R.Luke Dubois

R. Luke DuBois curriculum vitae Education Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Columbia University, New York, NY Doctor of Musical Arts, Music Composition. May 2003. Dissertation: Applications of Generative String-Substitution Systems in Computer Music. Composition Studies with Fred Lerdahl and Jonathan Kramer. Specialization in computer music composition and perception systems for interactive control/performance. Development of interface software for real-time signal processing. Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Columbia University, New York, NY Master of Arts, Music Composition. May 1999. Columbia College, Columbia University, New York, NY Bachelor of Arts, Music / History, May 1997. Teaching Brooklyn Experimental Media Center, Polytechnic Institute of NYU, Brooklyn, Assistant Professor, 2008-present. NY DM2113, Sound Studio I. Instructor. DM2144, Interaction Design. Instructor. DM2186, Algorithmic Composition. Instructor. DM3113, Sound Studio II. Instructor. DM6113, Sound Studio Seminar. Instructor. DM9903, Thesis Research. Instructor. DM9103, Synaesthesia. Instructor. DM9103, Real-Time Multimedia. Instructor. Computer Music Center, Columbia University, New York, NY Staff Researcher, 2004-2008. Adjunct Assistant Professor, 2003-2004. Graduate Teaching Fellow, 1997-2003. R6006, Sound/Image (Fall 2003). Instructor. R6006, Sound/Image (Spring 2003). Co-instructor. G6610, Computer Music (Fall 2002-Spring 2003). Teaching Assistant. G6615, Movement-Sound Interaction (Spring 2001). Co-instructor. V2205, MIDI Music Production Techniques (Summer 1999, Summer 2000, Spring 2001-2002). Instructor. R6505, Interactivity Outside the Box (Spring 2000). Guest lecturer. G6630, Recorded Sound (Spring 1999 to Spring 2001). Teaching Assistant. G6601, Basic Electroacoustics (Fall 1998 to Fall 2000). Teaching Assistant. Interactive Telecommunications Program, Tisch School of the Arts, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Communications, 2003-2009. New York University, New York, NY H79.2422, Live Image Processing and Performance. -

An Exploration of Extra-Musical Issues in the Music of Don Byron Steven Craig Becraft

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 An Exploration of Extra-Musical Issues in the Music of Don Byron Steven Craig Becraft Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXPLORATION OF EXTRA-MUSICAL ISSUES IN THE MUSIC OF DON BYRON By STEVEN CRAIG BECRAFT A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright 2005 Steven Craig Becraft All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approve the treatise of Steven Craig Becraft defended on September 26, 2005. ____________________________ Frank Kowalsky Professor Directing Treatise ____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Outside Committee Member ____________________________ Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member ____________________________ Patrick Meighan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Don Byron: Thank you for making such fascinating music. I thoroughly appreciate your artistic vision, your intellect, and your phenomenal technique as a clarinetist. The knowledge I have gained and the new perspective I have on music and society as a result of completing the research for this treatise has greatly impacted my life. I am grateful for the support of the Arkansas Federation of Music Clubs, especially Janine Tiner, Ruth Jordan, and Martha Rosenbaum for awarding me the 2005 Marie Smallwood Thomas Scholarship Award that helped with final tuition and travel expenses. My doctoral committee has been a great asset throughout the entire degree program. -

Great Instrumental

I grew up during the heyday of pop instrumental music in the 1950s and the 1960s (there were 30 instrumental hits in the Top 40 in 1961), and I would listen to the radio faithfully for the 30 seconds before the hourly news when they would play instrumentals (however the first 45’s I bought were vocals: Bimbo by Jim Reeves in 1954, The Ballad of Davy Crockett with the flip side Farewell by Fess Parker in 1955, and Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1956). I also listened to my Dad’s 78s, and my favorite song of those was Raymond Scott’s Powerhouse from 1937 (which was often heard in Warner Bros. cartoons). and to records that my friends had, and that their parents had - artists such as: (This is not meant to be a complete or definitive list of the music of these artists, or a definitive list of instrumental artists – rather it is just a list of many of the instrumental songs I heard and loved when I was growing up - therefore this list just goes up to the early 1970s): Floyd Cramer (Last Date and On the Rebound and Let’s Go and Hot Pepper and Flip Flop & Bob and The First Hurt and Fancy Pants and Shrum and All Keyed Up and San Antonio Rose and [These Are] The Young Years and What’d I Say and Java and How High the Moon), The Ventures (Walk Don't Run and Walk Don’t Run ‘64 and Perfidia and Ram-Bunk-Shush and Diamond Head and The Cruel Sea and Hawaii Five-O and Oh Pretty Woman and Go and Pedal Pusher and Tall Cool One and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue), Booker T. -

New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival – April 2–6, 2013 –

NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL – APRIL 2–6, 2013 – nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 6 COMMITTEE & STAFF 8 PROGRAMS & NOTES 9 INSTALLATIONS 43 COMPOSERS & PERFORMERS 45 SUPPORT 72 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS – Special thanks to the Doctoral Student Council of Graduate Center CUNY for their support. Additional thanks to: 4 DIRECTOR’s WELCOME Welcome to NYCEMF 2013! On behalf of the Steering Committee, it is my great pleasure to welcome you to the New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival this year. We have planned an exciting program of 21 concerts in many different locations throughout New York City, and we hope that you will enjoy all of them. I would like first to acknowledge the assistance and support of the many people who have helped make this event possible: – Dr. David Olan, Executive Director of the Ph.D./D.M.A. programs in Music at the City University Graduate Center, and Kelli Kathman, manager of the concert office, for their assistance in organizing our use of Elebash and Segal Halls. – Brian Fennelly, Louis Karchin, and Elizabeth Hoffman of New York University, for the inclusion of our first concert as part of their Washington Square Contemporary Music series. – Fractured Atlas/RocketHub for their support in our fund-raising program, and all the donors who contributed to our campaign. – The Doctoral Students’ Council of the Graduate Center, for their support in contributing to the printing of the program book. – The Steering Committee, who met for many hours in planning the events and who single-handedly selected all the music for the festival. -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

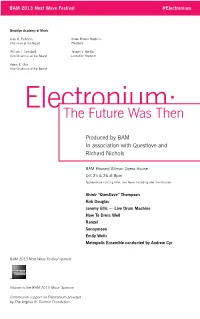

Electronium:The Future Was Then

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #Electronium Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Electronium:The Future Was Then Produced by BAM In association with Questlove and Richard Nichols BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 25 & 26 at 8pm Approximate running time: two hours including one intermission Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Kirk Douglas Jeremy Ellis — Live Drum Machine How To Dress Well Rahzel Sonnymoon Emily Wells Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Commission support for Electronium provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Electronium Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr: Kristin Lee, violin (concertmaster) Francisco Fullana, violin Karen Kim, viola Hiro Matsuo, cello Mellissa Hughes, soprano Virginia Warnken, alto Geoffrey Silver, tenor Jonathan Woody, bass-baritone ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Arrangements by Daniel Felsenfeld, DD Jackson, Patrick McMinn and Anthony Tid Lighting design by Albin Sardzinski Sound engineering by John Smeltz Stage design by Alex Delaunay Stage manager Cheng-Yu Wei Electronium references the first electronic synthesizer created exclusively for the composition and performance of music. Initially created for Motown by composer-technologist Raymond Scott, the electronium was designed but never released for distribution; the one remaining machine is undergoing restoration. Complemented by interactive lighting and aural mash-ups, the music of Electronium: The Future Was Then honors the legacy of the electronium in a production that celebrates both digital and live music interplay. -

2013 DL Art Science Conference Program.Pdf

Across Boundaries, Across Abilities Deep Listening Institute, Ltd. 77 Cornell St, Suite 303 PO Box 1956 Kingston, NY 12401 www.deeplistening.org [email protected] facebook.com/deep.listener Twitter @DeepListening What is Deep Listening? There’s more to listening than meets the ear. Pauline Oliveros describes Deep Listening as “listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what one is doing.” Basically Deep Listening, as developed by Oliveros, explores the difference between the involuntary nature of hearing and the voluntary, selective nature – exclusive and inclusive -- of listening. The practice includes bodywork, sonic meditations, interactive performance, listening to the sounds of daily life, nature, one’s own thoughts, imagination and dreams, and listening to listening itself. It cultivates a heightened awareness of the sonic environment, both external and internal, and promotes experimentation, improvisation, collaboration, playfulness and other creative skills vital to personal and community growth. ; 2 Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) Troy, New York My hope is to inspire scientific inquiry and research on listening as well as to bring the world community together to share ideas and practice Deep Listening. --Pauline Oliveros, Founder of Deep Listening Institute Dear Conference Attendees, I am extremely pleased to welcome you to Deep Listening: Art/Science, the First International Conference on Deep Listening! This three-day event will feature an amazing array of lectures, workshops, posters and experience-focused presentations on a number of topics related to the art and science of listening. This includes many distinguished and long-time members of the Deep Listening community as well as a host of scholars and creators who approach listening from unique perspectives.