Equation Vocabulary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11. Three Dimensional Analytic Geometry and Vectors

Chapter 11. Three dimensional analytic geometry and vectors. Section 11.5 Quadric surfaces. Curves in R2 : x2 y2 ellipse + =1 a2 b2 x2 y2 hyperbola − =1 a2 b2 parabola y = ax2 or x = by2 A quadric surface is the graph of a second degree equation in three variables. The most general such equation is Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + Dxy + Exz + F yz + Gx + Hy + Iz + J =0, where A, B, C, ..., J are constants. By translation and rotation the equation can be brought into one of two standard forms Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + J =0 or Ax2 + By2 + Iz =0 In order to sketch the graph of a quadric surface, it is useful to determine the curves of intersection of the surface with planes parallel to the coordinate planes. These curves are called traces of the surface. Ellipsoids The quadric surface with equation x2 y2 z2 + + =1 a2 b2 c2 is called an ellipsoid because all of its traces are ellipses. 2 1 x y 3 2 1 z ±1 ±2 ±3 ±1 ±2 The six intercepts of the ellipsoid are (±a, 0, 0), (0, ±b, 0), and (0, 0, ±c) and the ellipsoid lies in the box |x| ≤ a, |y| ≤ b, |z| ≤ c Since the ellipsoid involves only even powers of x, y, and z, the ellipsoid is symmetric with respect to each coordinate plane. Example 1. Find the traces of the surface 4x2 +9y2 + 36z2 = 36 1 in the planes x = k, y = k, and z = k. Identify the surface and sketch it. Hyperboloids Hyperboloid of one sheet. The quadric surface with equations x2 y2 z2 1. -

A Quick Algebra Review

A Quick Algebra Review 1. Simplifying Expressions 2. Solving Equations 3. Problem Solving 4. Inequalities 5. Absolute Values 6. Linear Equations 7. Systems of Equations 8. Laws of Exponents 9. Quadratics 10. Rationals 11. Radicals Simplifying Expressions An expression is a mathematical “phrase.” Expressions contain numbers and variables, but not an equal sign. An equation has an “equal” sign. For example: Expression: Equation: 5 + 3 5 + 3 = 8 x + 3 x + 3 = 8 (x + 4)(x – 2) (x + 4)(x – 2) = 10 x² + 5x + 6 x² + 5x + 6 = 0 x – 8 x – 8 > 3 When we simplify an expression, we work until there are as few terms as possible. This process makes the expression easier to use, (that’s why it’s called “simplify”). The first thing we want to do when simplifying an expression is to combine like terms. For example: There are many terms to look at! Let’s start with x². There Simplify: are no other terms with x² in them, so we move on. 10x x² + 10x – 6 – 5x + 4 and 5x are like terms, so we add their coefficients = x² + 5x – 6 + 4 together. 10 + (-5) = 5, so we write 5x. -6 and 4 are also = x² + 5x – 2 like terms, so we can combine them to get -2. Isn’t the simplified expression much nicer? Now you try: x² + 5x + 3x² + x³ - 5 + 3 [You should get x³ + 4x² + 5x – 2] Order of Operations PEMDAS – Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally, remember that from Algebra class? It tells the order in which we can complete operations when solving an equation. -

Verifying the Unification Algorithm In

Verifying the Uni¯cation Algorithm in LCF Lawrence C. Paulson Computer Laboratory Corn Exchange Street Cambridge CB2 3QG England August 1984 Abstract. Manna and Waldinger's theory of substitutions and uni¯ca- tion has been veri¯ed using the Cambridge LCF theorem prover. A proof of the monotonicity of substitution is presented in detail, as an exam- ple of interaction with LCF. Translating the theory into LCF's domain- theoretic logic is largely straightforward. Well-founded induction on a complex ordering is translated into nested structural inductions. Cor- rectness of uni¯cation is expressed using predicates for such properties as idempotence and most-generality. The veri¯cation is presented as a series of lemmas. The LCF proofs are compared with the original ones, and with other approaches. It appears di±cult to ¯nd a logic that is both simple and exible, especially for proving termination. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Overview of uni¯cation 2 3 Overview of LCF 4 3.1 The logic PPLAMBDA :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 3.2 The meta-language ML :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 3.3 Goal-directed proof :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 3.4 Recursive data structures ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 4 Di®erences between the formal and informal theories 7 4.1 Logical framework :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.2 Data structure for expressions :::::::::::::::::::::: 8 4.3 Sets and substitutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 4.4 The induction principle :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 5 Constructing theories in LCF 10 5.1 Expressions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Writing the Equation of a Line

Name______________________________ Writing the Equation of a Line When you find the equation of a line it will be because you are trying to draw scientific information from it. In math, you write equations like y = 5x + 2 This equation is useless to us. You will never graph y vs. x. You will be graphing actual data like velocity vs. time. Your equation should therefore be written as v = (5 m/s2) t + 2 m/s. See the difference? You need to use proper variables and units in order to compare it to theory or make actual conclusions about physical principles. The second equation tells me that when the data collection began (t = 0), the velocity of the object was 2 m/s. It also tells me that the velocity was changing at 5 m/s every second (m/s/s = m/s2). Let’s practice this a little, shall we? Force vs. mass F (N) y = 6.4x + 0.3 m (kg) You’ve just done a lab to see how much force was necessary to get a mass moving along a rough surface. Excel spat out the graph above. You labeled each axis with the variable and units (well done!). You titled the graph starting with the variable on the y-axis (nice job!). Now we turn to the equation. First we replace x and y with the variables we actually graphed: F = 6.4m + 0.3 Then we add units to our slope and intercept. The slope is found by dividing the rise by the run so the units will be the units from the y-axis divided by the units from the x-axis. -

The Geometry of the Phase Diffusion Equation

J. Nonlinear Sci. Vol. 10: pp. 223–274 (2000) DOI: 10.1007/s003329910010 © 2000 Springer-Verlag New York Inc. The Geometry of the Phase Diffusion Equation N. M. Ercolani,1 R. Indik,1 A. C. Newell,1,2 and T. Passot3 1 Department of Mathematics, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA 2 Mathematical Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK 3 CNRS UMR 6529, Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France Received on October 30, 1998; final revision received July 6, 1999 Communicated by Robert Kohn E E Summary. The Cross-Newell phase diffusion equation, (|k|)2T =∇(B(|k|) kE), kE =∇2, and its regularization describes natural patterns and defects far from onset in large aspect ratio systems with rotational symmetry. In this paper we construct explicit solutions of the unregularized equation and suggest candidates for its weak solutions. We confirm these ideas by examining a fourth-order regularized equation in the limit of infinite aspect ratio. The stationary solutions of this equation include the minimizers of a free energy, and we show these minimizers are remarkably well-approximated by a second-order “self-dual” equation. Moreover, the self-dual solutions give upper bounds for the free energy which imply the existence of weak limits for the asymptotic minimizers. In certain cases, some recent results of Jin and Kohn [28] combined with these upper bounds enable us to demonstrate that the energy of the asymptotic minimizers converges to that of the self-dual solutions in a viscosity limit. 1. Introduction The mathematical models discussed in this paper are motivated by physical systems, far from equilibrium, which spontaneously form patterns. -

Numerical Algebraic Geometry and Algebraic Kinematics

Numerical Algebraic Geometry and Algebraic Kinematics Charles W. Wampler∗ Andrew J. Sommese† January 14, 2011 Abstract In this article, the basic constructs of algebraic kinematics (links, joints, and mechanism spaces) are introduced. This provides a common schema for many kinds of problems that are of interest in kinematic studies. Once the problems are cast in this algebraic framework, they can be attacked by tools from algebraic geometry. In particular, we review the techniques of numerical algebraic geometry, which are primarily based on homotopy methods. We include a review of the main developments of recent years and outline some of the frontiers where further research is occurring. While numerical algebraic geometry applies broadly to any system of polynomial equations, algebraic kinematics provides a body of interesting examples for testing algorithms and for inspiring new avenues of work. Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Notation 5 I Fundamentals of Algebraic Kinematics 6 3 Some Motivating Examples 6 3.1 Serial-LinkRobots ............................... ..... 6 3.1.1 Planar3Rrobot ................................. 6 3.1.2 Spatial6Rrobot ................................ 11 3.2 Four-BarLinkages ................................ 13 3.3 PlatformRobots .................................. 18 ∗General Motors Research and Development, Mail Code 480-106-359, 30500 Mound Road, Warren, MI 48090- 9055, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] URL: www.nd.edu/˜cwample1. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant DMS-0712910 and by General Motors Research and Development. †Department of Mathematics, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556-4618, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] URL: www.nd.edu/˜sommese. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant DMS-0712910 and the Duncan Chair of the University of Notre Dame. -

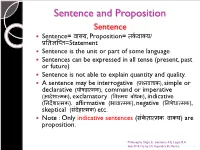

Logic- Sentence and Propositions

Sentence and Proposition Sentence Sentence= वा啍य, Proposition= त셍कवा啍य/ प्रततऻप्तत=Statement Sentence is the unit or part of some language. Sentences can be expressed in all tense (present, past or future) Sentence is not able to explain quantity and quality. A sentence may be interrogative (प्रश्नवाच셍), simple or declarative (घोषड़ा配म셍), command or imperative (आदेशा配म셍), exclamatory (ववमयतबोध셍), indicative (तनदेशा配म셍), affirmative (भावा配म셍), negative (तनषेधा配म셍), skeptical (संदेहा配म셍) etc. Note : Only indicative sentences (सं셍ेता配म셍तवा啍य) are proposition. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 1 All kind of sentences are not proposition, only those sentences are called proposition while they will determine or evaluate in terms of truthfulness or falsity. Sentences are governed by its own grammar. (for exp- sentence of hindi language govern by hindi grammar) Sentences are correct or incorrect / pure or impure. Sentences are may be either true or false. Philosophy Dept, E- contents-01( Logic-B.A Sem.III & IV) by Dr Rajendra Kr.Verma 2 Proposition Proposition are regarded as the material of our reasoning and we also say that proposition and statements are regarded as same. Proposition is the unit of logic. Proposition always comes in present tense. (sentences - all tenses) Proposition can explain quantity and quality. (sentences- cannot) Meaning of sentence is called proposition. Sometime more then one sentences can expressed only one proposition. Example : 1. ऩानीतबरसतरहातहैत.(Hindi) 2. ऩावुष तऩड़तोत (Sanskrit) 3. It is raining (English) All above sentences have only one meaning or one proposition. -

Data Types & Arithmetic Expressions

Data Types & Arithmetic Expressions 1. Objective .............................................................. 2 2. Data Types ........................................................... 2 3. Integers ................................................................ 3 4. Real numbers ....................................................... 3 5. Characters and strings .......................................... 5 6. Basic Data Types Sizes: In Class ......................... 7 7. Constant Variables ............................................... 9 8. Questions/Practice ............................................. 11 9. Input Statement .................................................. 12 10. Arithmetic Expressions .................................... 16 11. Questions/Practice ........................................... 21 12. Shorthand operators ......................................... 22 13. Questions/Practice ........................................... 26 14. Type conversions ............................................. 28 Abdelghani Bellaachia, CSCI 1121 Page: 1 1. Objective To be able to list, describe, and use the C basic data types. To be able to create and use variables and constants. To be able to use simple input and output statements. Learn about type conversion. 2. Data Types A type defines by the following: o A set of values o A set of operations C offers three basic data types: o Integers defined with the keyword int o Characters defined with the keyword char o Real or floating point numbers defined with the keywords -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis

First Order Logic and Nonstandard Analysis Julian Hartman September 4, 2010 Abstract This paper is intended as an exploration of nonstandard analysis, and the rigorous use of infinitesimals and infinite elements to explore properties of the real numbers. I first define and explore first order logic, and model theory. Then, I prove the compact- ness theorem, and use this to form a nonstandard structure of the real numbers. Using this nonstandard structure, it it easy to to various proofs without the use of limits that would otherwise require their use. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 An Introduction to First Order Logic 2 2.1 Propositional Logic . 2 2.2 Logical Symbols . 2 2.3 Predicates, Constants and Functions . 2 2.4 Well-Formed Formulas . 3 3 Models 3 3.1 Structure . 3 3.2 Truth . 4 3.2.1 Satisfaction . 5 4 The Compactness Theorem 6 4.1 Soundness and Completeness . 6 5 Nonstandard Analysis 7 5.1 Making a Nonstandard Structure . 7 5.2 Applications of a Nonstandard Structure . 9 6 Sources 10 1 1 Introduction The founders of modern calculus had a less than perfect understanding of the nuts and bolts of what made it work. Both Newton and Leibniz used the notion of infinitesimal, without a rigorous understanding of what they were. Infinitely small real numbers that were still not zero was a hard thing for mathematicians to accept, and with the rigorous development of limits by the likes of Cauchy and Weierstrass, the discussion of infinitesimals subsided. Now, using first order logic for nonstandard analysis, it is possible to create a model of the real numbers that has the same properties as the traditional conception of the real numbers, but also has rigorously defined infinite and infinitesimal elements. -

Chapter 1: Analytic Geometry

1 Analytic Geometry Much of the mathematics in this chapter will be review for you. However, the examples will be oriented toward applications and so will take some thought. In the (x,y) coordinate system we normally write the x-axis horizontally, with positive numbers to the right of the origin, and the y-axis vertically, with positive numbers above the origin. That is, unless stated otherwise, we take “rightward” to be the positive x- direction and “upward” to be the positive y-direction. In a purely mathematical situation, we normally choose the same scale for the x- and y-axes. For example, the line joining the origin to the point (a,a) makes an angle of 45◦ with the x-axis (and also with the y-axis). In applications, often letters other than x and y are used, and often different scales are chosen in the horizontal and vertical directions. For example, suppose you drop something from a window, and you want to study how its height above the ground changes from second to second. It is natural to let the letter t denote the time (the number of seconds since the object was released) and to let the letter h denote the height. For each t (say, at one-second intervals) you have a corresponding height h. This information can be tabulated, and then plotted on the (t, h) coordinate plane, as shown in figure 1.0.1. We use the word “quadrant” for each of the four regions into which the plane is divided by the axes: the first quadrant is where points have both coordinates positive, or the “northeast” portion of the plot, and the second, third, and fourth quadrants are counted off counterclockwise, so the second quadrant is the northwest, the third is the southwest, and the fourth is the southeast. -

Unification: a Multidisciplinary Survey

Unification: A Multidisciplinary Survey KEVIN KNIGHT Computer Science Department, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-3890 The unification problem and several variants are presented. Various algorithms and data structures are discussed. Research on unification arising in several areas of computer science is surveyed, these areas include theorem proving, logic programming, and natural language processing. Sections of the paper include examples that highlight particular uses of unification and the special problems encountered. Other topics covered are resolution, higher order logic, the occur check, infinite terms, feature structures, equational theories, inheritance, parallel algorithms, generalization, lattices, and other applications of unification. The paper is intended for readers with a general computer science background-no specific knowledge of any of the above topics is assumed. Categories and Subject Descriptors: E.l [Data Structures]: Graphs; F.2.2 [Analysis of Algorithms and Problem Complexity]: Nonnumerical Algorithms and Problems- Computations on discrete structures, Pattern matching; Ll.3 [Algebraic Manipulation]: Languages and Systems; 1.2.3 [Artificial Intelligence]: Deduction and Theorem Proving; 1.2.7 [Artificial Intelligence]: Natural Language Processing General Terms: Algorithms Additional Key Words and Phrases: Artificial intelligence, computational complexity, equational theories, feature structures, generalization, higher order logic, inheritance, lattices, logic programming, natural language