Songs of Kabir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems 2.Ed

Letitia E. Landon The improvisatrice; and other poems 2.ed. London : Hurst, Robinson [et al.], 1824 reference no. S54254 BELSER WISSENSCHAFTLICHER DIENST LICENSE AGREEMENT This LICENSE AGREEMENT constitutes an agreement between you (hereafter ‘Licensee’) and BELSER WISSENSCHAFTLICHER DIENST Ltd. (hereafter ‘Licensor’): ‘Licensor’ grants to the ‘Licensee’ a non-exclusive right to use and display this electronic book through the software ACROBAT READER on a single computer only (i.e., with a single CPU) at a single location. ‘Licensor’ reserves all rights not expressly granted to you as ‘Licensee’ in this LICENSE AGREEMENT. 1. Ownership of this electronic book: As ‘Licensee’, you own only the rights to use the electronic book as an authorized user. Authorized users may only use this electronic book and each of its pages for legitimate fair and personal use such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Outside this „Fair Use” (i.e. section of the United States Copyright Act) this electronic book and each of the full text pages you may not: (i) electronically transfer the electronic book – or parts of it - from one computer to another over a network (ii) make the electronic book available through a time-sharing service, network of computers, or other multiple user arrangements (iii) distribute copies of the electronic book or parts of it or related materials to any third party, whether for sale or otherwise (iv) modify, adapt, translate, reverse engineer, decompile, disassemble, rescan or prepare any derivative work based on this electronic book or any element thereof (v) make or distribute, whether for sale or other-wise, any hard copy or printed version of any page of the electronic book nor any portion thereof nor any work of yours containing the electronic book or any component thereof without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews citing the Copyright holder. -

Las Adaptaciones De Obras Del Teatro Español En El Cine Y El Influjo De Éste En Los Dramaturgos - Juan De Mata Moncho Aguirre Indice

Las adaptaciones de obras del teatro español en el cine y el influjo de éste en los dramaturgos - Juan de Mata Moncho Aguirre Indice Síntesis ....................................................................................................... i Abstract .....................................................................................................iv I. Prólogo ................................................................................................... 1 II. Épocas literarias ................................................................................. 14 1. Época Renacentista ......................................................................14 2. Teatro del siglo de oro ................................................................... 24 3. Teatro del siglo XVIII...................................................................... 52 4. Teatro del siglo XIX........................................................................ 58 5. Teatro del siglo XX....................................................................... 123 III. Conclusiones .................................................................................. 618 IV. Bibliografía....................................................................................... 633 V. Archivos documentales................................................................... 694 Las adaptaciones de obras del teatro español en el cine y el influjo de éste en los dramaturgos - Juan de Mata Moncho Aguirre Síntesis Al afrontar las vinculaciones de los dramaturgos -

Stay with God.Pdf

STAY WITH GOD A Statement in Illusion on Reality Third edition 1990 By Francis Brabazon An Avatar Meher Baba Trust Online Release June 2011 Copyright © Avatar’s Abode Trust 1984 Source and short publication history: This Online Release reproduces the third edition, which is the first illustrated edition (1990), of Stay With God, published by New Humanity Books, Melbourne, Australia. Stay With God was originally published by Edwards and Shwa for Garuda Books, Woombye, Queensland, in 1959, and a second edition was published in 1977 by Meher House Publications, Bombay, India. eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non- facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba’s lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects—such as lineation and font—the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. -

Stated Meeting of Tuesday, April 29, 2014

THE COUNCIL STATED MEETING OF TUESDAY, APRIL 29, 2014 THE COUNCIL with the brilliance of a million suns, to remove all obstacles today and for always for this Council; Minutes of the Proceedings for the and may we achieve STATED MEETING peace, peace, peace onto us all. of Tuesday, April 29, 2014, 1:41 p.m. Thank you. The Public Advocate (Ms. James) Council Member Dromm moved to spread the Invocation in full upon the Acting President Pro Tempore and Presiding Officer Record. Council Members At this point, the Speaker (Council Member Mark-Viverito) asked for a Moment Melissa Mark-Viverito, Speaker of Silence in memory of the following individual: Maria del Carmen Arroyo Vincent J. Gentile Carlos Menchaca Inez D. Barron Vanessa L. Gibson I. Daneek Miller Basil Paterson, 87, political leader, labor lawyer, and member of the influential “Gang of Four” Democrats from Harlem, died on April 16, 2014. He leaves behind Fernando Cabrera David G. Greenfield Annabel Palma his wife Portia, and their two sons Daniel Paterson and former New York State Margaret S. Chin Vincent M. Ignizio Antonio Reynoso Governor David Paterson. At this point, the Speaker (Council Member Mark- Viverito) yielded the floor to Council Member Dickens who spoke in respectful Andrew Cohen Corey D. Johnson Donovan J. Richards memory of Basil Paterson. Costa G. Constantinides Ben Kallos Ydanis A. Rodriguez Robert E. Cornegy, Jr. Andy L. King Deborah L. Rose LAND USE CALL UPS Elizabeth S. Crowley Peter A. Koo Helen K. Rosenthal Laurie A. Cumbo Karen Koslowitz Ritchie J. Torres M-49 Chaim M. -

A Million Suns PDF Book

A MILLION SUNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Beth Revis | 404 pages | 23 Nov 2012 | RAZORBILL | 9781595145376 | English | New York, United States A Million Suns PDF Book Can you do it? I freakin' loved the second installment. I know I'm not the target audience for this one, but I found the story extremely one- dimensional and so highly unbelievable. He was constantly making horrible decisions and wasn't really helpful. That's great. Seller Inventory Oceans Will Part Acoustic. The use of handwriting on the album and single sleeves was the band's idea. Save Cancel. Shannon Noll. What do you think? Stay and Wait He barrels through the mangled doorway although he's limping; why is he limping? Yes No. Namespaces Article Talk. Sign In Register. The best part of the book was the plot and pacing. Signed Copy First edition copy. Get the ship running and get to the new Earth for once, but this is not the case, because it is so easy to point to the things that go wrong, but it is harder to give a hand and make them right again. I'm excited to find out what awaits them. Instead of describing a relationship's end, the record was written in perspective of a relationship that is working. What If This Storm Ends? I just feel like they were constantly making dumb decisions throughout the book. Error rating book. But she's incredibly selfish and whiny in a sense. That said, I wanted to see where Revis was going to take the story next. -

Night-Of-Love.Pdf

Have you ever thought that on one night you could save a thousand souls? This book dares you to try! Have you ever felt really present at Calvary, united to Mary, as you assisted at Mass? This book will surely take you there! Have you ever understood the Message of Fatima from personal experience, from personal repa ration? This book will give you that experience! “No Rosary we ever said in our lives was as meaningful as that led by John Haffert at an all night vigil,” said Dorothy Murarescu, leader of the all night vigil movement in Philadelphia. As a result, he was called to help at all night vigils all over the East...and finally responded by writing this book. Oyïflht Of J2oue % by John M. Haffert This is a book about night vigils begun by Our Lord (see page 23), to help turn back the tide of evil. They are nights of conversion and grace. (Original printing, 1966, with Imprimatur of Bishop George W. Ahr, S.T.D., Bishop of Trenton) Revised Edition Printed In the United States In 1997 by: The 101 Foundation, Inc. P.O. Box 151 Asbury, New Jersey 08802 Phone: 908-689 8792 Fax: 908-689 1957 © Mr. John M. Haffert, 1966 & 1997 ISBN # 1-890137-02-2 This Night of Love is dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart of Mary in reparation for my sins and the sins of the world. Ofifht O f JZoeve Table of Contents Page Part 1. Chapter: 1) A TJiousand Souls 1- 2) What Is The Greatest Benefit? 10. -

Passengers Rewrite LAST.Fdr Title Page

PASSENGERS by Jon Spaihts 2601 2 N D STR EE T SA N TA MO NI CA CA 90405 FADE IN: EXT. INTERSTELLAR SPACE A million suns shine in the dark. A STARSHIP cuts through the night: a gleaming white cruiser. Galleries of windows. Flying decks and observation domes. On the hull: EXCELSIOR - A HomeStead Company Starship. The ship flashes through a nebula. Space-dust sparkles as it whips over the hull, betraying the ship’s dizzying speed. The nebula boils in the ship’s wake. The Excelsior rockets on, spotless and beautiful as a daydream. INT. STARSHIP EXCELSIOR - GRAND CONCOURSE A wide plaza. Its lofty atrium cuts through seven decks, creating tiers of promenades framing a vast skylight. The promenades are empty. Chairs unoccupied. Beetle-like robots vacuum the carpets and wax the floors. CAFETERIA Super-modern and gleaming. Hundreds of tables, all empty. FORWARD OBSERVATION DECK Lounge furniture and star-filled windows. Completely deserted. A robot on spindly legs washes the glass. HIBERNATION BAY Endless corridors lined with vertical glass tubes. Inside each tube stands a PASSENGER. Eyes closed in sleep. If they’re breathing you can’t tell by looking. They sleep on their feet, leaning against padded supports. Straps secure them in place; sensors adhere to their skin. They wear shorts and tank tops with HomeStead Company logos. We survey their faces. No children, no senior citizens. Men and women of every ethnicity in the prime of their lives. We settle on one man. JIM PRESTON, 38. Sound asleep. A small display on his pod reads: JAMES PRESTON Rate 2 Mechanical Engineer Denver, Colorado 2. -

March 2019 – Vol. 7, Issue 3

3375 Church Lane Duluth, GA 30096 Rev. Ronald L. Bowens Pastor MARCH 2019 Vol. 7, Issue 3 FRIENDSHIP’S VOICE Peace can be considered freedom from disturbance, tranquility, calmness, restfulness, lawfulness or order. When we accept Christ as our Lord and INSIDE THIS ISSUE Savior, we can have this “Peace” even when the storms are raging around us because we can lean on God and rest upon his Word; in the Peace .......................................................... Cover midst of the storm, we can have contentment and calmness. Hymn of the Month ............................................ 2 Inspirations from the Psalms .............................. 3 Believers should be civil, forgiving and loving towards each other for Signs of the Season ............................................. 7 peace to reign among God’s people—then we will see fertility in the Health Ministry ................................................... 8 church for the blessings produced by the Word of God. Outreach Ministry............................................... 9 Marriage Class Valentine Event ........................ 10 Men’s Ministry .................................................. 14 Colossians 3:15: “And let the peace of God rule in your hearts, to the Women’s Ministry ............................................ 16 which also ye are called in one body; and be ye thankful.” Senior’s Ministry ............................................... 19 Black History ..................................................... 21 True Peace comes when we exercise the -

Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien De Troyes Through Bernard of Clairvaux

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2016 Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux Carrie D. Pagels University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Christianity Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pagels, Carrie D., "Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3732 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Carrie D. Pagels entitled "Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in French. Mary McAlpin, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: John Romeiser, Anne-Helene Miller, Mary Dzon Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Parables of Love: Reading the Romances of Chrétien de Troyes through Bernard of Clairvaux A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Carrie D. -

William Parker and the AIDS Quilt Songbook Kyle Ferrill

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 William Parker and the AIDS Quilt Songbook Kyle Ferrill Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC WILLIAM PARKER AND THE AIDS QUILT SONGBOOK By KYLE FERRILL A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Kyle Ferrill defended on March 28, 2005. _____________________________________ Stanford Olsen Professor Directing Treatise _____________________________________ Timothy Hoekman Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Roy Delp Committee Member _____________________________________ Larry Gerber Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................... Page v Abstract .......................................................................................... Page vii 1. Introduction and Biography ............................................................... Page 1 Infection and Action ....................................................................... Page 2 The premiere and publication of The AIDS Quilt Songbook .......... Page 6 2. Analysis of the Songs....................................................................... -

Complete Issue

International Journal editorial board of Euro-Mediterranean Studies Nabil Mahmoud Alawi, An-Najah University, Palestine issn 1855-3362 Nadia Al-Bagdadi, Central European The aim of the International Journal of University, Hungary Euro-Mediterranean Studies is to promote Ahmad M. Atawneh, Hebron University, intercultural dialogue and exchanges Palestine between societies, develop human Pamela Ballinger, Bowdoin College, usa resources, and to assure greater Klemen Bergant, University of Nova Gorica, mutual understanding in the Euro- Slovenia Mediterranean region. Roberto Biloslavo, University of Primorska, L’objectif de la revue internationale d’etudes Slovenia Euro-Méditerranéennes est de promouvoir Rémi Brague, Panthéon-Sorbonne University, le dialogue interculturel et les échanges France entre les sociétés, développer les Holger Briel, University of Nicosia, Cyprus ressources humaines et assurer une Donna Buchanan, University of Illinois usa compréhension mutuelle de qualité au at Urbana-Champaign, sein de la région euro-méditerranéenne. Costas M. Constantinou, University of Nicosia, Cyprus Namen Mednarodne revije za evro-mediteranske Claudio Cressati, University of Udine, študije je spodbujanje medkulturnega Italy dialoga in izmenjav, razvoj cloveškihˇ Yamina El Kirat El Allame, University virov in zagotavljanje boljšega Mohammed V,Morocco medsebojnega razumevanja v Julia Elyachar Mastnak, Scientific Research evro-mediteranski regiji. Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences ijems is indexed in ibss and Arts and doaj. Said Ennahid, -

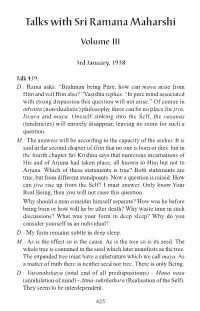

Talks with Ramana Maharshi

Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi Volume III 3rd January, 1938 Talk 439. D.: Rama asks: “Brahman being Pure, how can maya arise from Him and veil Him also? “Vasishta replies: “In pure mind associated with strong dispassion this question will not arise.” Of course in advaita (non-dualistic) philosophy there can be no place for jiva, Isvara and maya. Oneself sinking into the Self, the vasanas (tendencies) will entirely disappear, leaving no room for such a question. M.: The answers will be according to the capacity of the seeker. It is said in the second chapter of Gita that no one is born or dies: but in the fourth chapter Sri Krishna says that numerous incarnations of His and of Arjuna had taken place, all known to Him but not to Arjuna. Which of these statements is true? Both statements are true, but from different standpoints. Now a question is raised: How can jiva rise up from the Self? I must answer. Only know Your Real Being, then you will not raise this question. Why should a man consider himself separate? How was he before being born or how will he be after death? Why waste time in such discussions? What was your form in deep sleep? Why do you consider yourself as an individual? D.: My form remains subtle in deep sleep. M.: As is the effect so is the cause. As is the tree so is its seed. The whole tree is contained in the seed which later manifests as the tree. The expanded tree must have a substratum which we call maya.