Annual Report to the Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burned to Be Wild: Science, Society, and Ecological Conservation In

BURNED TO BE WILD: SCIENCE, SOCIETY, AND ECOLOGICAL CONSERVATION IN THE SOUTHERN LONGLEAF PINE by ALBERT GLOVER WAY (Under the Direction of Paul S. Sutter) ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the development of ecological conservation and science in the southern coastal plain’s dominant ecosystem – the longleaf pine-grassland forest. It examines how the impetus for conservation changed over the long twentieth-century from concerns over bodily health, landscape aesthetics, and recreation, into concerns for ecological integrity and landscape diversity, and argues that the biocentric turn in twentieth-century science and society was rooted in the very processes of production that it sought to moderate. To unearth this story, it focuses on the region surrounding Thomasville, Georgia and Tallahassee, Florida, known as the Red Hills, where wealthy northerners came after the Civil War and Reconstruction in search of health, and remained to convert failing farms and plantations into winter retreats and hunting preserves. In the years covered here, roughly 1880-1960, this land of wealth and poverty was a working landscape that produced a variety of goods and supported a large number of people; yet, at the same time it was a conservation landscape and laboratory where a great deal of scientific knowledge about the longleaf pine-grassland environment came to light. The central figure in this dissertation is Herbert L. Stoddard, an ornithologist, wildlife biologist, and ecological forester who came to the Red Hills in 1924 as an agent of the U.S. Bureau of the Biological Survey to examine the life history and preferred habitat of the bobwhite quail. -

DATA.Shtti ^E ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM

Form No. 10-300 \Q^ DATA.SHtti ^e ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Greenwood Plantation AND/OR COMMON Greenwood Plantation LOCATION STREET &NOMBER Cairo Road, Ga. 84 NOT F,OR PUBLICATION CITY. TOW W . Thomasville CONGRESSIONAL2nd-Dawson DISTRICTMa thi VICINITY OF STATE Georgia CODE 10 COUNTY Thomas CODE 273 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED X_AGRI CULTURE —MUSEUM V _ BUILDING(S) _f±PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL -^PRIVATE RESIDENCE .JfelTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —MILITARY -OTHER: hunting prese^jve OWNER OF PROPERTY .. Mr,4 :Jotm flay Whitney STREET & NUMBER = 110! West-31st St. CITY. TOWN New York City STATE New York 10020 VICINITY OF [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE.REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETc. Thomas_, County_ . Courthouse-, . , STREET & NUMBER N. Broad St. CITY. TOWN STATE Thomasville Georgia 31792 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Thomasville Landmarks Architectural Inventory DATE V 10/1/69 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Thomasville Landmarks Inc. CITY, TOWN STATE Box 44, Thomasville Georgia, 31792 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS .XALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The main house at Greenwood Plantation was built between 1833 and 1844 and was designed by English architect, John Wind. -

This Is Marist

86 MARIST FOOTBALL RED FOXES 87 This is Marist Marist is a comprehensive institution with its 210-acre main campus in the Hudson River Valley in MARIST COLLEGE DISTINCTIONS New Yois a comprehensive institution with its 210-acre main campus in the Hudson River Valley in New York, a campus in Florence, Italy, extension centers throughout New York, and educational offerings n Marist is ranked as a top ten Regional University by U.S. News. The College is also #2 on the U.S. News list of Most Innovative Schools. around the world through its online programs. Marist is distinguished by high-quality faculty, innovative Marist is embarking on the creation of a medical school with the nonprofit healthcare organization, Nuvance Health. program offerings, a beautiful riverfront campus, and a technological platform that is comparable to those n Marist has launched a center at 420 Fifth Avenue in New York City to house its innovative corporate training, graduate and professional of the best research universities in the world. education programs. HISTORY & MISSION OF MARIST COLLEGE n The Marist Fashion Program is ranked as one of the top fashion programs globally by the premier industry publication Business of Fashion. Marist is dedicated to helping students develop the intellect and character required for enlightened, ethical, and productive lives in the global community of the 21st century. These goals derive from the n Marist prepares its students well for life after graduation, as evidenced by the success of our alumni in winning prestigious fellowships such Marist Brothers, a teaching order that originated in France in 1817, settled in Poughkeepsie in 1905, and as Fulbrights, Goldwaters, and Teach for America; admission to top graduate schools like Harvard, Yale, and Georgetown; and positions at established the Marist Normal Training School in 1929. -

2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy

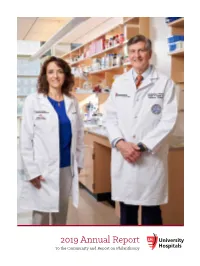

2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy Cover: Leading UH research on COVID-19, Grace McComsey, MD, Vice President of Research and Associate Chief Scientific Officer, UH Clinical Research Center, Rainbow Babies & Children's Foundation John Kennell Chair of Excellence in Pediatrics, and Division Chief of Infectious Diseases, UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital; and Robert Salata, MD, Chairman, Department of Medicine, STERIS Chair of Excellence in Medicine and and Master Clinician in Infectious Disease, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and Program Director, UH Roe Green Center for Travel Medicine and Global Health, are Advancing the Science of Health and the Art of Compassion. Photo by Roger Mastroianni The 2019 UH Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy includes photographs obtained before Ohio's statewide COVID-19 mask mandate. INTRODUCTION REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY 5 Letter to Friends 38 Letter to our Supporters 6 UH Statistics 39 A Gift for the Children 8 UH Recognition 40 Honoring the Philanthropic Spirit 41 Samuel Mather Society UH VISION IN ACTION 42 Benefactor Society 10 Building the Future of Health Care 43 Revolutionizing Men's Health 12 Defining the Future of Heart and Vascular Care 44 Improving Global Health 14 A Healing Environment for Children with Cancer 45 A New Game Plan for Sports Medicine 16 UH Community Highlights 48 2019 Endowed Positions 18 Expanding the Impact of Integrative Health 54 Annual Society 19 Beating Cancer with UH Seidman 62 Paying It Forward 20 UH Nurses: Advancing and Evolving Patient Care 63 Diamond Legacy Society 22 Taking Care of the Browns. -

Yale University Catalogue, 1860 Yale University

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale University Catalogue Yale University Publications 1860 Yale University Catalogue, 1860 Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_catalogue Recommended Citation Yale University, "Yale University Catalogue, 1860" (1860). Yale University Catalogue. 49. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_catalogue/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Yale University Publications at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale University Catalogue by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATALOGUE OF THE OFFICERS AND STUDENTS IN YALE COLLEGE, WITH A STATEMENT OF THE COURSE OF INSTRUCTION IN THE VARIOUS DEPARTMENTS. 1860-61. P It IX TED BY E. H ~YES, 426 C II APEL T. 1860. 2 THE GOVERNOR, LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR, AND SIX SENIOR SENATORS OF THE STATE ARE, ex officio, )(EMBERS OF THE CORPORATION. PB.ESJ:DENT. REv. THEODORE D. WOOLSEY, D. D., LL. D. FELLOWS.• Hrs Exe. WILLIAM A. BUCKINGHAM, NoRWICH. His IloNoR JULIUS CATLIN, HARTFORD. REv. DAVID SMITH, D. D., DuanAl'tl. REV. NOAH PORTER, D. D., FARl\IINGTON. REV. JEREMIAH DAY, D. D., LL. D., NEW HAVEN. REV. JOEL HAWES, D. D., HARTFORD. REV. JOSEPH ELDRIDGE, D. D., NORFOLK. REV. GEORGE A. CALHOUN, D. D., COVENTRY. REv. GEORGE J. TILLOTSON, PuTNAl\l. REV. EDWIN R. GILBERT, WALLINGFORD. REV. JOEL H. LINSLEY, D. D., GREENWICH. HoN. ELISHA JOHNSON, HARTFORD. HoN. JOHN W. -

1916-1917 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

N BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY OBITUARY RECORD OF YALE GRADUATES I916-I917 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY NEW HAVEN Thirteenth Series No 10 July 1917 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Entered as second-class matter, August 30, 1906, at the-post-office at New Haven, Conn, under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894 The Bulletin, which is issued monthly, includes 1. The University Catalogue 2 The Reports of the President and Treasurer 3 The Pamphlets of the Several Schools 4 The Directory of Living Graduates THE TLTTLE, MOREHOtSE & TAYLOR COMPANY, NEW HAVEN, CONN OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YA1E UNIVERSITY Deceased dating the yea* ending JULY 1, 1917 INCLUDING THE RECORD OF A FEW WHO DIED PREVIOUSLY HITHERTO UNREPORTED [No 2 of the Seventh Printed Series, and No 76 of the whole Record The present Series consists of -frve numbers] OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the year ending JULY I, 1917, Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [No 2 of the Seventh Printed Series, and No 76 of the whole Record The present Series consists of five numbers ] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMIC DEPARTMENT) Robert Hall Smith, B.A. 1846 Born February 29, 1828, m Baltimore, Md Died September n, 1915, on Spesutia Island, Harford County, Md Robert Hall Smith was the son of Samuel W and Elinor (Donnell) Smith, and was born February 29, 1828, in Baltimore, Md. Through his father, whose parents were Robert and Margaret Smith, he traced his descent from Samuel Smith, who came to this country from Ballema- goragh, Ireland, in 1728, settling at Donegal, Lancaster County, Pa. -

Is Tiger Woods a Psy-Op?

return to updates Is Tiger Woods a Psy-op? by Miles Mathis First published April 14, 2016 As usual, this is just opinion, arrived at by personal research. Boy, I didn't see this one coming. I had no intention of writing about Tiger Woods, but as many of you know, the Masters was televised this weekend. So I was sort of pulled toward Tiger like a magnet. Although Tiger didn't play, whether or not he would play was the biggest story before the tournament. Since I have no TV reception, I didn't watch the tournament. I could have watched it online I guess, but I didn't. The first tug in the direction of this paper occurred when I made my weekly call home to talk to Mom and Dad. They were watching the Masters. My father had been a tournament golfer as a young man, winning the Club Championship when he was only 17. He toyed with the idea of turning pro, but decided (correctly, I would say) that he didn't have the temperament for it. He is a bit of a hot- head. I was also a tournament golfer in my teens, although I never reached the level of my father. Although I won some tournaments, I bowed out by the age of 16. Despite shooting in the 60s by then, I had discovered that golf was just another cheating contest, and I wasn't really prepared to get into all that. At the time, I imagined that the cheating only occurred at the lower levels, where there was no oversight. -

Thomas Abbey

MEMORIAL of CAPTAIN THOMAS ABBEY His Ancestors and Descendants of THE ABBEY FAMILY PATHFINDERS, SOLDIERS -AND PIONEER SETTLERS OF CONNECTICUT, ITS WESTERN RESERVE IN OHIO AND THE GREAT WEST. Inscription and Seal at the Base of the Pedestal of the Statue. The embattled farmers at Lexington, the men who already had arms, ,vho seized them and came forth in order to assert the independence and political freedom of then1selves and their neighbors. That is the ideal picture of A.mer-ica-the rising of a nation. \\rOODRO\V WILSON, January 29, 1916. This is the Second Edition of this book revised and condensed 1917 INSCRIBE'D. TO THE MEMORY OF OUR FOREFATHERS 'The memory of our fathers should be the ,vatchvlord of liberty throughout the land; for, imperfect as they were, the \vorld before had not seen their like, nor ,vill it soon, we fear~ behold their like again. Such models of moral excellence, such apostles of civil and religious liberty, such shades of the illustrious dead looking do,vn upon their descendants ,vith approbation or reproof, according as they follo,v or depart from the good ,vay, constitute a censorship inferior only to the eye of God; and to ridicule them is national suicide.-Beecher. MEMORIAL of CAPTAIN THOMAS ABBEY His Ancestors and Descendants of THE ABBEY FAMILY PATHFINDERSt SOLDIERS .AND PIONEER SETTLERS OF CONNECTICUTt ITS WESTERN RESERVE IN OHIO AND THE GREAT WEST. Inscription and Seal at the Base of the Pedestal of the Statue. ERECTED BY HIS GREAT.-GRANDDAUGHTER FRANCES MARIA ABBEY WIFE OF JOEL FRANCIS FREEMAN 1836.-1910 Her sons: _-\LDEN FREElVL-\N. -

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

: UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION; THE : IN RE MTBE LITIGATION COMMISSIONER OF THE NEW MASTER FILE No. 1:00-1898 JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF : MDL No. 1358 (VSB) ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION; and THE ADMINISTRATOR OF THE NEW : JERSEY SPILL COMPENSATION Civil Action No. 08 Civ. FUND, : 00312 Plaintiffs, : JUDICIAL CONSENT ORDER AS TO EQUILON ENTERPRISES LLC, V. : MOTIVA ENTERPRISES LLC, SHELL OIL COMPANY, SHELL OIL ATLANTIC RICHFIELD CO., et : PRODUCTS COMPANY LLC and al., SHELL TRADING (US) COMPANY : ONLY Defendants. : This matter was opened to the Court by Christopher S. Porrino, Attorney General of New Jersey, Deputy Attorney General Gwen Farley appearing, and Leonard Z. Kaufmann, Esq. of Cohn Lifland Pearlman Herrmann & Knopf LLP, and Scott E. Kauff, Esq. of the Law Offices of John K. Dema, P.C., and Michael Axline, Esq. of Miller Axline P.C., and Tyler Wren, Esq. of Berger & Montague P.C., Special Counsel to the Attorney General, appearing, as attorneys for plaintiffs New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection ("DEP" or “Department”) and the Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection ("Commissioner"), in their named capacity, as parens patriae, and as trustee of the natural resources of New Jersey, and the Administrator of the New Jersey Spill Compensation Fund ("Administrator"), and Richard Wallace and 1 Peter Condron, Crowell & Moring LLP, 1001 Pennsylvania Ave., NW, Washington, D.C. 20004, appearing as attorneys for defendants Equilon Enterprises LLC, Motiva Enterprises LLC, Shell Oil Company, Shell Oil Products Company LLC and Shell Trading (US) Company (collectively “the Shell Defendants”), and these Parties having amicably resolved their dispute before trial: I. -

Town of Rhinebeck Local Waterfront Revitalization Program

Town of Rhinebeck Local Waterfront Revitalization Program Adopted: Town Board, February 13, 2007 Approved: NYS Secretary of State Lorraine A. Cortés-Vázquez, April 24, 2007 Concurred: U.S. Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, July 27, 2007 This Local Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP) has been adopted and approved in accordance with provisions of the Waterfront Revitalization of Coastal Areas and Inland Waterways Act (Executive Law, Article 42) and its implementing regulations (6 NYCRR 601). Federal concurrence on the incorporation of this Local Waterfront Revitalization Program into the New York State Coastal Management Program as a routine program change has been obtained in accordance with provisions of the U.S. Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-583), as amended, and its implementing regulations (15 CFR 923). The preparation of this program was financially aided by a federal grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. Federal Grant No. NA-82-AA-D-CZ068. The New York State Coastal Management Program and the preparation of Local Waterfront Revitalization Programs are administered by the New York State Department of State, Division of Coastal Resources, One Commerce Plaza, 99Washington Avenue, Albany, New York 12231. SECTION I LOCAL WATERFRONT REVITALIZATION AREA BOUNDARY SECTION II INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS A. OVERVIEW......................................... SECTION II - 1 B. EXISTING LAND USE................................ SECTION II - 3 C. ZONING . .......................................... SECTION II - 8 D. ENVIRONMENTAL FEATURES ..................... SECTION II - 11 E. RECREATION AND OPEN SPACE AREAS. ........... SECTION II - 23 F. -

Our Community. Our Calling

Our Community. Our Calling. 2016 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY AND REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY DEAR FRIENDS, Throughout University Hospitals’ 150-year history, all that we do has been guided by the inspiration of our founders, who felt called to share their own good fortune by providing vital health care services for the needs of our community. Others have generously followed their example. And the result today is a health system delivering care close to home for the people of Northeast Ohio and an academic medical center renowned for advanced procedures and treatment options, groundbreaking clinical research and education for our next generation of clinicians. Without a doubt, University Hospitals is the hometown health care provider for this proud region. We’re honored to be such an integral part of this community’s history, and we keep moving forward to meet evolving needs – today, and for years to come. More than 30,000 UH physicians, nurses, employees and volunteers serve more than 1 million patients and families from Ashtabula to Ashland to Amherst. We offer the region’s largest network of primary care providers, a dozen community hospitals, two rehabilitation hospitals and more than 40 community health centers featuring nearby care and services. And like the region we serve, UH has Cleveland as its heart. During our 150th anniversary year in 2016, our main campus in Cleveland took on a new name: University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center. The campus includes our medical and surgical hospital, UH Seidman Cancer Center, UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital and UH MacDonald Women’s Hospital. -

Hudson River Valley Scenic Areas of Statewide Significance

Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 SCENIC POLICIES ............................................................................................................................... 3 EVALUATING NEW YORK'S COASTAL SCENIC RESOURCES .......................................................................... 3 New York's Scenic Evaluation Method ................................................................................................. 4 Application of the Method .................................................................................................................... 5 Candidate Scenic Areas of Statewide Significance ............................................................................... 5 SCENIC AREAS OF STATEWIDE SIGNIFICANCE IN THE HUDSON RIVER REGION ............................................... 6 BENEFITS OF DESIGNATION ................................................................................................................ 7 THE HUDSON RIVER STUDY ................................................................................................................ 7 MAP: HUDSON RIVER SCENIC AREAS.................................................................................................. 10 COLUMBIA-GREENE NORTH SCENIC AREA OF STATEWIDE SIGNIFICANCE .............................