The Effect of Soil and Irrigation Management on Grapevine Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

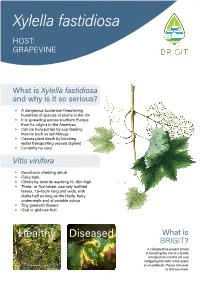

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

Basic Soil Science W

Basic Soil Science W. Lee Daniels See http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/430/430-350/430-350_pdf.pdf for more information on basic soils! [email protected]; 540-231-7175 http://www.cses.vt.edu/revegetation/ Well weathered A Horizon -- Topsoil (red, clayey) soil from the Piedmont of Virginia. This soil has formed from B Horizon - Subsoil long term weathering of granite into soil like materials. C Horizon (deeper) Native Forest Soil Leaf litter and roots (> 5 T/Ac/year are “bio- processed” to form humus, which is the dark black material seen in this topsoil layer. In the process, nutrients and energy are released to plant uptake and the higher food chain. These are the “natural soil cycles” that we attempt to manage today. Soil Profiles Soil profiles are two-dimensional slices or exposures of soils like we can view from a road cut or a soil pit. Soil profiles reveal soil horizons, which are fundamental genetic layers, weathered into underlying parent materials, in response to leaching and organic matter decomposition. Fig. 1.12 -- Soils develop horizons due to the combined process of (1) organic matter deposition and decomposition and (2) illuviation of clays, oxides and other mobile compounds downward with the wetting front. In moist environments (e.g. Virginia) free salts (Cl and SO4 ) are leached completely out of the profile, but they accumulate in desert soils. Master Horizons O A • O horizon E • A horizon • E horizon B • B horizon • C horizon C • R horizon R Master Horizons • O horizon o predominantly organic matter (litter and humus) • A horizon o organic carbon accumulation, some removal of clay • E horizon o zone of maximum removal (loss of OC, Fe, Mn, Al, clay…) • B horizon o forms below O, A, and E horizons o zone of maximum accumulation (clay, Fe, Al, CaC03, salts…) o most developed part of subsoil (structure, texture, color) o < 50% rock structure or thin bedding from water deposition Master Horizons • C horizon o little or no pedogenic alteration o unconsolidated parent material or soft bedrock o < 50% soil structure • R horizon o hard, continuous bedrock A vs. -

So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee

Agricultural Extension Service The University of Tennessee PB 1689 So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee 1 conditions. American grapes are So You Want to Grow versatile. They may be used for fresh consumption (table grapes) or processed into wine, juice, jellies or Grapes in Tennessee some baked products. Seedless David W. Lockwood, Professor grapes are used mostly for fresh Plant Sciences and Landscape Systems consumption, with very little demand for them in wines. Yields of seedless varieties do not match ennessee has a long history of grape production. Most recently, those of seeded varieties. They are T passage of the Farm Winery Act in 1978 stimuated an upsurge of also more susceptible to certain interest in grape production. If you are considering growing grapes, the diseases than the seeded American following information may be useful to you. varieties. French-American hybrids are crosses between American bunch 1. Have you ever grown winery, the time you spend visiting and V. vinifera grapes. Their grapes before? others will be a good investment. primary use is for wine. uccessful grape production Vitis vinifera varieties are used S requires a substantial commit- 3. What to grow for wine. Winter injury and disease ment of time and money. It is a American problems seriously curtail their marriage of science and art, with a - seeded growth in Tennessee. good bit of labor thrown in. While - seedless Muscadines are used for fresh our knowledge of how to grow a French-American hybrid consumption, wine, juice and jelly. crop of grapes continues to expand, Vitis vinifera Vines and fruits are not very we always need to remember that muscadine susceptible to most insects and some crucial factors over which we Of the five main types of grapes diseases. -

CHABLIS LES CLOS GRAND CRU 2017 100% Chardonnay Although I’Ve Said It Before, It’S Worth Repeating: Drouhin Is One of the Top Producers in Chablis

CHABLIS LES CLOS GRAND CRU 2017 100% Chardonnay Although I’ve said it before, it’s worth repeating: Drouhin is one of the top producers in Chablis. - WineReviewOnline.com The vineyard site is the largest and probably most famous Grand Cru, located between Valmur on the left and Blanchot on the right. The exposure is responsible for its generous and powerful character. It is the cradle of Chablis, already recognized by the medieval monks as a superb location for planting a vineyard. The term “Les Clos” (enclosure, in French) probably refers to the surrounding wall that they built to fence off the parcel. This wall is no longer in existence. At the end of the 19th Century the vineyard was devastated by the phylloxera disease. In the 1960’s, Robert Drouhin was one of the first Beaune propriétaires to bring it back to life. Vineyard site: • Soil: the Kimmeridgian limestone contains millions of tiny marine fossils embedded in a kind of whitish mortar which may have been once the bottom of the sea...hundreds of million years ago. • This marine origin gives the wines of Chablis their unique flavour. • Drouhin estate: 1.3 ha. (3.212 acres). Average age of the vines: 37 years. Viticulture: • Plantation density: 8,000 to 10,000 stocks/ha. • Pruning: double Guyot “Vallée de la Marne” (for its resistance to frost). • Yield: we aim for a lower yield in order to extract all possible nuances from the terroir. • Average yield at the Domaine: 43.2hl/ha (authorized for the appellation is now 54hl/ha). Ageing • Type: in oak barrel (0% new wood). -

A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible Through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application

agronomy Article A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application Ján Horák 1,* , Tatijana Kotuš 1, Lucia Toková 1, Elena Aydın 1 , Dušan Igaz 1 and Vladimír Šimanský 2 1 Department of Biometeorology and Hydrology, Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Engineering, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] (T.K.); [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (D.I.) 2 Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agrobiology and Food Resources, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Recent findings of changing climate, water scarcity, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions have brought major challenges to sustainable agriculture worldwide. Biochar application to soil proves to be a suitable solution to these problems. Although the literature presents the pros and cons of biochar application, very little information is available on the impact of repeated application. In this study, we evaluate and discuss the effects of initial and reapplied biochar (both in rates of 0, 10, and 20 t ha−1) combined with N fertilization (at doses of 0, 40, and 80 kg ha−1) on soil properties and N O emission from Haplic Luvisol in the temperate climate zone (Slovakia). Results showed that 2 biochar generally improved the soil properties such as soil pH(KCl) (p ≤ 0.05; from acidic towards Citation: Horák, J.; Kotuš, T.; Toková, moderately acidic), soil organic carbon (p ≤ 0.05; an increase from 4% to over 100%), soil water L.; Aydın, E.; Igaz, D.; Šimanský, V. -

Oregon Wine Research Institute Viticulture & Enology Technical Newsletter Spring 2019

OREGON WINE RESEARCH INSTITUTE VITICULTURE & ENOLOGY TECHNICAL NEWSLETTER SPRING 2019 Welcome to the Spring 2019 Newsletter This edition contains research updates and a comprehensive list of In this issue: publications summarizing research conducted by faculty of the Oregon • Cluster thinning research: Wine Research Institute at Oregon State University. Dr. Patty Skinkis, OSU What are the limits? Viticulture Extension Specialist and Professor, opens the newsletter with • Effective microbial an article on canopy yield management. Dr. James Osborne, OSU Enology monitoring is key to Extension Specialist and Associate Professor, discusses the importance of preventing microbial spoilage effective microbial monitoring in preventing microbial spoilage. Lastly, Sarah • Fits like a glove: Improving Lowder, OSU Graduate Research Assistant, along with Dr. Walt Mahaffee, sampling techniques to Research Plant Pathologist, USDA-ARS, provide an article on techniques to monitor Qol fungicide monitor Qol fungicide resistant grape powdery mildew. resistant grape powdery This issue is posted online at the OWRI website https://owri.oregonstate. mildew edu/owri/extension-resources/owri-newsletters. Learn more about our • Research Publications research and engage with the core faculty here. Cheers, The OWRI Team Editorial Team Crop thinning research: What are the limits? Denise L. Dewey Dr. Patty Skinkis, Viticulture Extension Specialist and Professor, OSU Lead Editor Oregon Wine Research Institute [email protected] The yield-quality paradigm has long driven vineyard management decision- making, with growers focusing on the level of cluster thinning needed to Dr. Patty Skinkis reach target yields. The general thought is that reducing yield will improve Viticulture Editor ripeness and quality, allowing the remaining fruit to accumulate desirable Oregon Wine Research Institute [email protected] aroma, flavor, and color compounds. -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Irrigation of Wi in Rapes

42 NO VEMBER/DECEMBER 2001 WINEGR OWING ative. The same can be said of a plant's water potential. For example, when more water is Irrigation lost from a leaf via transpiration than moves into the leaf from the vascular tissue, its water potential will become more negative due to a relative increase in its solute concentration. of w i rapes This is important as water in plants and soils moves from regions where water potential is relatively high to regions where water potential is rela- tively low. Such differences in water in potential will result in movement of water from cell to cell within a plant or from regions within the soil profile that Cal Lorry E. WIIIIams y.t portion of the growing season in contain more moisture to those with Department of Viticulture Enology these areas and vineyard water use less. University of California-Qavis, and can be greater than the soil's water One way to measure the water Kearney Agricultural Center reservoir after the winter rainfall, potential of a plant organ in the field supplemental irrigation of vineyards (such as a leaf) is by using a pressure SYNOPSIS: How much irrigation water is may be required at some point dur- chamber. required to grow quality winegrapes ing summer months. The leaf's petiole is cut and the leaf depends upon site, the stage of vine quickly placed into the chamber with growth, row spacing, size of the vine's IRRIGATION MANAGEMENT the cut end of the petiole protruding canopy, and amount of rainfall occur- No matter where grapevines are out of the chamber. -

Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis Vinifera During Lasiodiplodia Theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis vinifera during Lasiodiplodia theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions Micael F. M. Gonçalves 1 , Rui B. Nunes 1, Laurentijn Tilleman 2 , Yves Van de Peer 3,4,5 , Dieter Deforce 2, Filip Van Nieuwerburgh 2, Ana C. Esteves 6 and Artur Alves 1,* 1 Department of Biology, CESAM, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] (M.F.M.G.); [email protected] (R.B.N.) 2 Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Campus Heymans, Ottergemsesteenweg 460, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (F.V.N.) 3 Department of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Center for Plant Systems Biology, VIB, 9052 Ghent, Belgium 5 Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0028, South Africa 6 Faculty of Dental Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Health (CIIS), Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Estrada da Circunvalação, 3504-505 Viseu, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-234-370-766 Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019; Published: 3 December 2019 Abstract: Lasiodiplodia theobromae is one of the most aggressive agents of the grapevine trunk disease Botryosphaeria dieback. Through a dual RNA-sequencing approach, this study aimed to give a broader perspective on the infection strategy deployed by L. theobromae, while understanding grapevine response. Approximately 0.05% and 90% of the reads were mapped to the genomes of L. -

An Economic Survey of the Wine and Winegrape Industry in the United States and Canada

An Economic Survey of the Wine and Winegrape Industry in the United States and Canada Daniel A. Sumner, Helene Bombrun, Julian M. Alston, and Dale Heien University of California, Davis Revised draft December 2, 2001 The wine industry in the United States and Canada is new by Old World standards but old by New World standards. The industry has had several rebirths, so specifying its age may depend on the purpose of the investigation. In the colonial and post-colonial period up through the middle of the 19th Century, it was a relatively tiny industry with imports accounting for almost all of the still meager consumption of quality wine in the region (Winkler, et al.). There was gradual development in the latter half of the 19th century, but wine production in the United States and Canada only began to develop significantly with the expansion of the California industry early in the 20th century (Carosso; Hutchinson). Then the industry needed to be recreated after the prohibition era from 1920 to 1932. More recently, in a sense, the industry was reborn again thirty or so years ago with an aggressive movement towards higher quality. The geography of the industry is relatively simple. Despite some wine and winegrape production in Canada and most states in the United States, California is the location of more than 90 percent of grape crush and about 85 percent of the wine production in North America (Wine Institute). Therefore, most of the discussion of grape and wine production in this chapter focuses on California. The discussion of demand and policy issues, of course, covers all of the United States and Canada. -

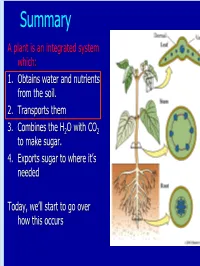

Summary a Plant Is an Integrated System Which: 1

Summary A plant is an integrated system which: 1. Obtains water and nutrients from the soil. 2. Transports them 3. Combines the H2O with CO2 to make sugar. 4. Exports sugar to where it’s needed Today, we’ll start to go over how this occurs Transport in Plants – Outline I.I. PlantPlant waterwater needsneeds II.II. TransportTransport ofof waterwater andand mineralsminerals A.A. FromFrom SoilSoil intointo RootsRoots B.B. FromFrom RootsRoots toto leavesleaves C.C. StomataStomata andand transpirationtranspiration WhyWhy dodo plantsplants needneed soso muchmuch water?water? TheThe importanceimportance ofof waterwater potential,potential, pressure,pressure, solutessolutes andand osmosisosmosis inin movingmoving water…water… Transport in Plants 1.1. AnimalsAnimals havehave circulatorycirculatory systems.systems. 2.2. VascularVascular plantsplants havehave oneone wayway systems.systems. Transport in Plants •• OneOne wayway systems:systems: plantsplants needneed aa lotlot moremore waterwater thanthan samesame sizedsized animals.animals. •• AA sunflowersunflower plantplant “drinks”“drinks” andand “perspires”“perspires” 1717 timestimes asas muchmuch asas aa human,human, perper unitunit ofof mass.mass. Transport of water and minerals in Plants WaterWater isis goodgood forfor plants:plants: 1.1. UsedUsed withwith CO2CO2 inin photosynthesisphotosynthesis toto makemake “food”.“food”. 2.2. TheThe “blood”“blood” ofof plantsplants –– circulationcirculation (used(used toto movemove stuffstuff around).around). 3.3. EvaporativeEvaporative coolingcooling. -

Some Biochemical Aspects of Vascular Wilts*

SOME BIOCHEMICAL ASPECTS OF VASCULAR WILTS* BY K. LAKSHMINAKAYANAN (University Botany Laboratory, Madras-5) TOXIN : GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS [N recent years considerable attention has been directed towards the study of microbial metabolic products by a number of workers in different countries (Raistrick, Arnstein and Cook in England, Gaumann and his school of workers in Switzerland, Dimond, Waggoner, Scheffer and Walker in the States) in view of their complicity in the production of many diseases by pathogens. They have been loosely called as toxins. The term toxin has been applied with so many different meanings in different contexts that it has become difficult to define it in precise terms. In therapeutics, the term is used to denote specific organic nitrogenous compounds produced by bacteria, in such diseases as tetanus, gas gangrene, diphtheria, etc. The term ' Wilting Toxin' was first applied by G~tumann (1950, 1951) to denote toxic metaoblites of fungal origin as enniatins, lycomarasmine, javanicin, etc., that were toxic to higher plants and claimed to be the primary cause of some or other of the syndrome of wilts. Vascular wilts were thus classified under toxigenic wilting. Toxins were claimed to be synthesized by the parasites (fungi or bacteria) as regular metabolic products in the course of their normal activity enter into the vascular system of the host plants and carried to the different part s of the plants wherein they initiate the various symptoms observed in the different organs. Dimond and Waggoner (1953 b) suggested a new term 'vivotoxin' defined as 'a substance produced in the infected host by the pathogen and/or its host which functions in the production of the disease but is not itself the initial inciting agent'.