Eschatology in the Greek Psalter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Septuagintal Isaian Use of Nomos in the Lukan Presentation Narrative

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects The eptuaS gintal Isaian Use of Nomos in the Lukan Presentation Narrative Mark Walter Koehne Marquette University Recommended Citation Koehne, Mark Walter, "The eS ptuagintal Isaian Use of Nomos in the Lukan Presentation Narrative" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 33. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/33 THE SEPTUAGINTAL ISAIAN USE OF ΝΌΜΟΣ IN THE LUKAN PRESENTATION NARRATIVE by Mark Walter Koehne, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT THE SEPTUAGINTAL ISAIAN USE OF ΝΌΜΟΣ IN THE LUKAN PRESENTATION NARRATIVE Mark Walter Koehne, B.A., M.A. Marquette University, 2010 Scholars have examined several motifs in Luke 2:22-35, the ”Presentation” of the Gospel of Luke. However, scholarship scarcely has treated the theme of νόμος, the Νόμος is .תורה Septuagintal word Luke uses as a translation of the Hebrew word mentioned four times in the Presentation narrative; it also is a word in Septuagintal Isaiah to which the metaphor of light in Luke 2:32 alludes. In 2:22-32—a pivotal piece within Luke-Acts—νόμος relates to several themes, including ones David Pao discusses in his study on Isaiah’s portrayal of Israel’s restoration, appropriated by Luke. My dissertation investigates, for the first time, the Septuagintal Isaian use of νόμος in this pericope. My thesis is that Luke’s use of νόμος in the Presentation pericope highlight’s Jesus’ identity as the Messiah who will restore and fulfill Israel. -

Are There Maccabean Psalms in the Psalter?

Bibliotheca Sacra 105 (Jan. 1948): 44-55. Copyright © 1948 by Dallas Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. Department of Semitics and Old Testament ARE THERE MACCABEAN PSALMS IN THE PSALTER? BY CHARLES LEE FEINBERG, TH.D., PH.D. Perhaps one of the most important questions in the mat- ter of dating the Psalter is that of the presence or absence of Maccabean psalms in the collection. Scholars differ wide- ly on the subject of such psalms in the Psalter, some finding a large number, others noting but a handful, while still others declaring the improbability of any such compositions in the Bible. The trend today is clear enough, however. Rowley notes: "At the beginning of the present century it was common to hold that a large number of the psalms was not composed until the Maccabean period. Such a view made the compilation of the Psalter so late that it could hardly be supposed that the Temple choirs of the Chron icler's day could have used this Hymn Book. Today there is a general tendency to find few, if any, Maccabean psalms, but on the contrary a good deal of ancient and pre-exilic material, though it is unlikely that any part of our Psalter was collected in its present form before the return from the exile."1 W. T. Davison contents himself with the general remark that there were probably such psalms.2 Driver proceeds very cautiously in reviewing the opinions of Olshausen and Reuss on this type of psalm, and thinks there would have been more prominent marks of such a period in the diction and style of the psalms.3 J. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

An Examination of Isaiah 66:17

Sometimes the Center is the Wrong Place to Be: An Examination of Isaiah 66:17 Kevin Malarkey Theology Given the Hebrew Bible as our only historical source, the period of the Israelites’ return to Judah and restoration of Jerusalem seems to be one of religious, social, and political anarchy; the Biblical record is wrought with historical lacunae and contradictions which ultimately leave us in the proverbial dark concerning the epoch.1 Historical-Biblical scholarship must, it appears, be content to do without a coherent and comprehensive narrative fully describing the repatriated Israelites’ situation. But, this is not to say that our knowledge of the period is wholly deficient; from a more studious examination of the texts we might be able to glean more than just isolated minutiae floating through the void. We can certainly assert that a portion of the exiled Israelites, the ones most interested in preserving their identity as specially chosen by God,2 would have adopted conservative attitudes regarding authentic religious worship. While some of the exiles may have made forays into religious syncretism and cultural assimilation (and most likely did, given the fact that some elected not to return to Palestine after Cyrus’ liberation), others refused acquiescence to such syncretism and assimilation on the grounds that authentic God-worship could not be genuinely undertaken in Babylon and should not be sullied by the taint of other gods. Indeed, a group of exiles did return to Jerusalem, intent on reestablishing authentic God- worship in the land and rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem as the locale of this worship. -

Isaiah 56–66

Isaiah 56–66 BERIT OLAM Studies in Hebrew Narrative & Poetry Isaiah 56–66 Paul V. Niskanen Chris Franke Series Editor A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Ann Blattner. Unless otherwise noted, all translations from Scripture are the author’s. © 2014 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Niskanen, Paul. Isaiah 56–66 / Paul V. Niskanen. pages cm. — (BERIT OLAM: studies in Hebrew narrative & poetry) “A Michael Glazier book.” ISBN 978-0-8146-5068-4 — ISBN 978-0-8146-8256-2 (ebook) 1. Bible. Isaiah, LVI–LXVI—Commentaries. I. Title. BS1520.5.N57 2014 224'.107—dc23 2014008292 CONTENTS List of Abbreviations .........................................vii Introduction ................................................ix Isaiah 56–57 ..................................................1 Isaiah 58 ....................................................17 Isaiah 59 ....................................................27 Isaiah 60 ....................................................35 -

Project 119 Bible Reading Plan January 3-February 27, 2021

Project 119 Bible Reading Plan January 3-February 27, 2021 About the Project 119 Bible Reading Plan Sunday, January 3– Saturday, January 9 Sunday, January 17 – Saturday, January 23 Sunday, January 3 Sunday, January 17 John 1:1-28 | Psalms 12, 13, 14 | Isaiah 17 John 7:53-8:30| Psalm 34 | Isaiah 31 In this current iteration of the Project 119 Bible reading Monday, January 4 Monday, January 18 plan, you will find three Scripture readings listed for each John 1:29-end | Psalm 17 | Isaiah 18 John 8:31-end| Psalm 35 | Isaiah 32 day of the week. There is a New Testament reading, an Tuesday, January 5 Tuesday, January 19 Old Testament reading, and a selection from the Book of John 2 | Psalm 18:1-19 | Isaiah 19 John 9 | Psalms 32, 36 | Isaiah 33 Psalms. If you read all three passages each day, you will Wednesday, January 6 Wednesday, January 20 John 3:1-21| Psalm 18:20-50 | Isaiah 20 John 10:1-21 | Psalm 37:1-18 | Isaiah 34 read the entire New Testament each year, most of the Old Thursday, January 7 Thursday, January 21 Testament every two years, and the book of Psalms three John 3:22-end| Psalm 19 | Isaiah 21 John 10:22-end | Psalm 37:19-40 | Isaiah 35 times each year. Friday, January 8 Friday, January 22 John 4:1-26| Psalms 20, 21 | Isaiah 22 John 11:1-44 | Psalm 40 | Isaiah 36 You are encouraged to read as much of the Bible as you can Saturday, January 9 Saturday, January 23 John 4:27-end| Psalm 22 | Isaiah 23 John 11:45-end| Psalms 39, 41 | Isaiah 37 each day. -

Isaiah 17:1 1 an Oracle Concerning Damascus: “See, Damascus Will No Longer Be a City but Will Become a Heap of Ruins

Revelation Lesson 1 Handout Isaiah 17:1 1 An oracle concerning Damascus: “See, Damascus will no longer be a city but will become a heap of ruins. Once Syria’s largest city, Aleppo has been the worst-hit city in the country since the Battle of Aleppo began in 2012 as part of the ongoing Syrian Civil War. Now a series of before-and-after photos reveals just how much the once- vibrant historical city has been marred by war. 1 Ray Stedman in his book God’s Final Word says: It is no accident that the book of Revelation appears as the last book of the Bible. Revelation gathers all the threads of theme and historic events contained in the rest of the Bible, weaving them into a seamless whole. The entire scope of human history and of eternity itself comes into brilliant focused in the book of Revelation. 2 Revelation 1:3 Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of the prophecy, and heed the things which are written in it; for the time is near. J. Barton Payne’s Encyclopedia of Biblical Prophecy lists 1,239 prophecies in the Old Testament and 578 prophecies in the New Testament, for a total of 1,817.. • There would be “many nations” against Tyre (Ezekiel 26: 3) • Her walls and towers would be torn down (Ezekiel 26: 4) • Her soil would be scraped away and she would become a shining bare rock (Ezekiel 26: 4) • • Fishermen would use the area for drying nets (Ezekiel 26: 5) • Settlements in the countryside would be slaughtered (Ezekiel 26: 6) • • King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon would come against Tyre (Ezekiel 26: 7) • • He would lay siege and tear down Tyre’s walls and houses (Ezekiel 26: 12) 3 • Tyre’s stones, woodwork and soil would be thrown in the water (Ezekiel 26: 12) Bible prophecy: Isaiah 7:14 Prophecy written: Between 701-681 BC Prophecy fulfilled: About 5 BC Isaiah 7:14: Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel. -

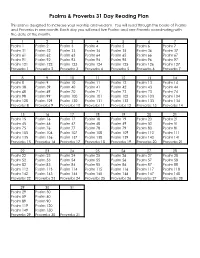

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) Calvin, Jean (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Calvin found Psalms to be one of the richest books in the Bible. As he writes in the introduction, "there is no other book in which we are more perfectly taught the right manner of praising God, or in which we are more powerfully stirred up to the performance of this religious exercise." This comment- ary--the last Calvin wrote--clearly expressed Calvin©s deep love for this book. Calvin©s Commentary on Psalms is thus one of his best commentaries, and one can greatly profit from reading even a portion of it. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on chapters 67 through 92. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on Psalms 67-92 1 Psalm 67 2 Psalm 67:1-7 3 Psalm 68 5 Psalm 68:1-6 6 Psalm 68:7-10 11 Psalm 68:11-14 14 Psalm 68:15-17 19 Psalm 68:18-24 23 Psalm 68:25-27 29 Psalm 68:28-30 33 Psalm 68:31-35 37 Psalm 69 40 Psalm 69:1-5 41 Psalm 69:6-9 46 Psalm 69:10-13 50 Psalm 69:14-18 54 Psalm 69:19-21 56 Psalm 69:22-29 59 Psalm 69:30-33 66 Psalm 69:34-36 68 Psalm 70 70 Psalm 70:1-5 71 Psalm 71 72 Psalm 71:1-4 73 Psalm 71:5-8 75 ii Psalm 71:9-13 78 Psalm 71:14-16 80 Psalm 71:17-19 84 Psalm 71:20-24 86 Psalm 72 88 Psalm 72:1-6 90 Psalm 72:7-11 96 Psalm 72:12-15 99 Psalm 72:16-20 101 Psalm 73 105 Psalm 73:1-3 106 Psalm 73:4-9 111 Psalm 73:10-14 117 Psalm 73:15-17 122 Psalm 73:18-20 126 Psalm 73:21-24 -

Journey Through the Bible: Book 2

Copyright © 2014 Christian Liberty Press ii Journey Through the Bible Copyright © 2014 by Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. Copies of this product may be made by the purchaser for personal or immediate family use only. Reproduction or transmission of this product—in any form or by any means—for use outside of the immediate family is not allowed without prior permission from the publisher. A publication of Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004 www.christianlibertypress.com www.shopchristianliberty.com Copyright © 2014 Christian Liberty Press Written by John Benz Layout and editing by Edward J. Shewan Copyediting by Diane C. Olson Cover design by Bob Fine Cover image and unit title images by David Miles, copyright © 2014 Christian Liberty Press Text images and charts copyright © 2008 Crossway, used with permission ISBN 978-1-935796-23-7 (print) ISBN 978-1-629820-23-1 (eBook PDF) Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................vii Note to Parents .....................................................................................................ix UNIT 1 Psalms, Song of Solomon, & Lamentations .........................................................1 Lesson 1 Part 1 Introduction to Poetry ..........................................................................................1 Lesson 1 Part 2 Introduction to Psalms ..........................................................................................3 -

DAILY BREAD the WORD of GOD in a YEAR by the Late Rev

DAILY BREAD THE WORD OF GOD IN A YEAR By the late Rev. R. M. M’Cheyne, M.A. THE ADVANTAGES • The whole Bible will be read through in an orderly manner in the course of a year. • Read the Old Testament once, the New Testament and Acts twice. Many of you may never have read the whole Bible, and yet it is all equally divine.“All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, and instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be perfect.” If we pass over some parts of Scripture, we will be incomplete Christians. • Time will not be wasted in choosing what portions to read. • Often believers are at a loss to determine towards which part of the mountains of spices they should bend their steps. Here the question will be solved at once in a very simple manner. • The pastor will know in which part of the pasture the flock are feeding. • He will thus be enabled to speak more suitably to them on the sabbath; and both pastor and elders will be able to drop a word of light and comfort in visiting from house to house, which will be more readily responded to. • The sweet bond of Christian unity will be strengthened. • We shall often be lead to think of those dear brothers and sisters in the Lord, who agree to join with us in reading these portions. We shall more often be led to agree on earth, touching something we shall ask of God.