A Cultural History of Three Regional Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stock Assessment of Winter Steelhead Trout in Goldstream, Sooke, Trent and Tsable Rivers, 2004

Stock Assessment of Winter Steelhead Trout in Goldstream, Sooke, Trent and Tsable Rivers, 2004 by: Scott Silvestri Fisheries Technician BC Conservation Foundation Greater Georgia Basin Steelhead Recovery Plan prepared for: British Columbia Conservation Foundation #206-17564 56A Surrey, BC V3S 1G5 and: Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection Vancouver Island Region 2080-A Labieux Road Nanaimo, BC V9T 6J9 December 2005 Stock Assessment of Winter Steelhead Trout in Goldstream, Sooke, Trent and Tsable Rivers, 2004 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS British Columbia Conservation Foundation staff including Adri Bigsby, James Craig, Mike McCulloch, Kevin Pellett, Brad Smith, Harlan Wright and the author conducted snorkel surveys and/or juvenile standing stock assessments in the four rivers examined. Additional snorkel survey support from Tony Massey1 and Ron Ptolemy2 was much appreciated. Additionally, Ron Ptolemy provided valuable stock assessment data. Thanks are also extended to Craig Wightman3 who was key in initiating this project and acted as scientific authority. Appreciation is extended to James Craig for editing this report. Funding for this project was provided by the BC Conservation Foundation through a Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection grant for the development of recreational hunting and fishing opportunities in British Columbia. 1 Fish Culture Technician, Freshwater Fisheries Society of BC, Duncan, BC 2 Standards/Guidelines Specialist, Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC 3 A/Manager, Salmon and Steelhead Recovery, Ministry of Environment, Nanaimo, BC ________________________________________________________________________________________________ British Columbia Conservation Foundation Greater Georgia Basin Steelhead Recovery Plan Stock Assessment of Winter Steelhead Trout in Goldstream, Sooke, Trent and Tsable Rivers, 2004 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ -

Activities & Tours

2019 VICTORIA ACTIVITIES & TOURS BOOK NOW! Ask Clipper’s friendly onboard or terminal agents for personal suggestions on the best ways to experience Victoria and Vancouver Island. Get On Board. Get Away. 800.888.2535 CLIPPERVACATIONS.COM THE BUTCHART GARDENS TEA AT THE EMPRESS Iconic Sights BUTCHART GARDENS & CITY HIGHLIGHTS TOUR Mar 30–Oct 13, 3.5 Hours Total, (2 at The Gardens). This unique Clipper Vacations tour includes a narrated deluxe motor coach ride from Victoria’s bustling Inner Harbour, along the Saanich Peninsula and past acres of farms with views of pastoral beauty. At The Butchart Gardens, you’ll see the Sunken Garden, The Japanese and Italian Gardens, English Rose Garden and the magnificent Ross Fountain, all linked by spacious lawns, streams and lily ponds. The Butchart Gardens is rated among the most beautiful gardens in the world. Departs from Clipper dock upon vessel arrival. Condé Nast Traveler named Butchart Gardens as one of the “14 most stunning botanical gardens around the world.” Afternoon Tea at The Gardens Includes: Your choice from selection of nine loose leaf teas paired with warm traditional delicacies, savory tea sandwiches and house-made sweets from The Butchart Gardens’ kitchen. OpenTable voted Butchart Garden’s, Dining Room Restaurant, “Top 100 Restaurants in Canada” three years running and “Top Outdoor Restaurants in Canada” THE BUTCHART GARDENS NIGHT ILLUMINATIONS A Spectacular Sight! Daily, Jun 15–Sep 2, 3.25* Hours. Night Illuminations is a spectacular display of hidden lights transforming this famous landscape, allowing visitors to view the gardens in a new light. Tour includes deluxe motor coach to the gardens and admissions. -

New Product Guide Fall Edition 2016

New Product Guide Fall Edition 2016 Rosewood Hotel Georgia Fairmont Pacific Rim Pacific Gateway Hotel at Vancouver Airport ACCOMMODATION FAIRMONT PACIFIC RIM ROSEWOOD HOTEL GEORGIA The Owner’s Suite Collection is a new collection of ten Introducing the enhanced specialty suites at The Private suites, each offering 800 square feet of opulence with a sofa Residences at Rosewood Hotel Georgia. These suites offer and dining room table in the living room, a king-sized canopy two, three and four-bedroom options for those seeking the bed, large walk-in closet and marble spa bathroom with a best Vancouver has to offer. Featured additions to booking soaker tub. Colourful art installations dress the walls of the these suites include roundtrip private airport transfers, space and every suite houses its own custom vinyl collection a VIP welcome amenity, nightly amenities and meet-and-greet and Rega RP1 turntable. Guests are welcomed with a curated with the hotel manager and chef concierge. Their Royal compilation of records based on their musical preferences or Suite also has private chef experiences available. can select their playlist upon arrival. Fairmont Gold services rosewoodhotels.com/en/hotel-georgia-vancouver are offered during their stay with private check-in, concierge and an exclusive lounge that overlooks the harbour. TRUMP INTERNATIONAL fairmont.com/pacific-rim-vancouver HOTEL & TOWER VANCOUVER PACIFIC GATEWAY HOTEL AT Opening January 2017, Trump International Hotel & Tower® Vancouver is a luxurious urban hotel. The famed Arthur VANCOUVER AIRPORT Erickson-designed twisting tower intricately weaves guest Pacific Gateway Hotel recently introduced their 1000 square rooms and suites around the tower and due to its unique foot two-bedroom suite featuring mountain views and two twisting tower design, every room and view is distinctive, king bedrooms as well as a separate living area, kitchenette with no two views exactly alike. -

GVHA-Indigenous-Business-Directory

1 Company Name Business Type Contact Details Website Alexander Traffic Traffic Control Dore Lafortune Alexander Traffic Control is a local company providing traffic N/A Control Ltd. Company control services. Aligned Design Commercial & Lana Pagaduan Aligned Design works in flooring installations and commer- www.aligneddesignfp.co Residential Painting and cial & residential painting. They are 100% Indigenous m (under construction) Flooring Installations owned and operated. AlliedOne Consulting IT Strategy Gina Pala AlliedOne Consulting is a management consulting service www.alliedoneconsulting. specializing in IT Strategy and leadership, as well as Cyber com Security. Animikii Web Design Company Jeff Ward Animikii is a web-services company building custom soft- www.animikii.com (Animikii ware, web-applications and websites. They work with lead- Gwewinzenhs) ing Indigenous groups across North America to leverage technology for social, economic and cultural initiatives. As a 100% Indigenous-owned technology company, Animikii works with their clients to implement solutions that amplify these efforts and achieve better outcomes for Indigenous people in these areas. Atrue Cleaning Commercial & Trudee Paul Atrue Cleaning is a local Indigenous owned cleaning compa- https:// Residential Cleaner ny specializing in commercial & residential cleaning, includ- www.facebook.com/ ing Airbnb rentals. trudeescleaning/ Brandigenous Corporate Branding Jarid Taylor Brandigenous is a custom branded merchandise supplier, www.facebook.com/ crafting authentic marketing merch with an emphasis of brandigenous/ quality over quantity. 2 Company Name Business Type Contact Details Website Brianna Marie Dick Artist- Songhees Nation Brianna Dick Brianna Dick is from the Songhees/Lekwungen Nation in N/A Tealiye Victoria through her father's side with roots to the Namgis Kwakwaka'wakw people in Alert Bay through her mother's side. -

Bc Historic News

British Columbia Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation | Vol.39 No. 4 | $5.00 This Issue: Tribute to Anne Yandle | Fraser Canyon Park | Bells | and More British Columbia History British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the British Columbia Historical A charitable society under the Income Tax Act Organized 31 October 1922 Federation Published four times a year. ISSN: print 1710-7881 online 1710-792X PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 Under the Distinguished Patronage of Her Honour British Columbia History welcomes stories, studies, The Honourable Iona Campagnolo. PC, CM, OBC and news items dealing with any aspect of the Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia history of British Columbia, and British Columbians. Honourary President Please submit manuscripts for publication to the Naomi Miller Editor, British Columbia History, John Atkin, 921 Princess Avenue, Vancouver BC V6A 3E8 Officers e-mail: [email protected] President Book reviews for British Columbia History, Patricia Roy - 602-139 Clarence St., Victoria, BC, V8V 2J1 Please submit books for review to: [email protected] Frances Gundry PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 First Vice President Tom Lymbery - 1979 Chainsaw Ave., Gray Creek, BC, V0B 1S0 Phone 250.227.9448 Subscription & subscription information: FAX 250.227.9449 Alice Marwood [email protected] 8056 168A Street, Surrey B C V4N 4Y6 Phone 604-576-1548 Second Vice President e-mail [email protected] Webb Cummings - 924 Bellevue St., New Denver, BC, V0G 1S0 Phone 250.358.2656 [email protected] -

Canadian Rockies

CANADIAN ROCKIES Banff-Lake Louise-Vancouver-Victoria September 3-11, 2014 INCLUDED IN YOUR TOUR: 4-Seasons Vacations Tour Director, Larry Alvey Tours of Calgary, Moraine Lake, Lake Louise, DELTA Airlines flights, Minneapolis to Calgary, Banff, Banff Mountain Gondola, Vancouver return Vancouver to Minneapolis Two day Daylight Rail, Banff to Vancouver, rail 8 Nights Hotel Accommodations gratuities included for Red, Silver and Gold Leaf 8 Meals: 5 breakfasts, 3 lunches, includes lunch Service at Chateau Lake Louise Baggage handling at hotels (1 bag per person) Deluxe motor coach in Canada All taxes DAY 1 WEDNESDAY Depart via Delta Airlines for Calgary, site of the famous Calgary Stampede. Our 1/2 day tour of this vibrant city includes the Olympic Park (site of the 1988 Winter Olympics) and the Stampede Grounds. DELTA BOW VALLEY DAY 2 THURSDAY (B) Our destination today is Banff, an alpine community nestled in the Rocky Mountains, a world famous resort. Tall peaks, wooded valleys, crystal-clear waters and canyons are all preserved in natural magnificence. Upon arrival in Banff, we tour lovely Bow Falls, Cascade Park, then ride the Banff Gondola to a mountain top for an unobstructed 360 degree view of the Banff town site. Our deluxe hotel is situated in the heart of Banff, providing ample opportunity to stroll the colorful streets of this quaint village. BANFF PARK LODGE (3 NIGHTS) DAY 3 FRIDAY (B, L) A wonderful day of sightseeing is in store for you today. We will visit beautiful Moraine Lake and the Valley of the Ten Peaks. Enjoy a lunch at Chateau Lake Louise. -

TB Nurses in BC 1895-1960

TB Nurses in B.C. 1895-1960: A Biographical Dictionary A record of nurses who worked to help bring tuberculosis under control during the years it was rampant in B.C. by Glennis Zilm, BSN, BJ, MA and Ethel Warbinek, BSN, MSN White Rock, B.C. 2006 [[Electronic Version October 2012]] Keywords: Tuberculosis, TB, Nursing history, British Columbia 2 © Copyright 2006 by Glennis Zilm and Ethel Warbinek Please note that copyright for photographs rests with the identified source. A limited research edition or five print copies and four CDs was made available to other researchers in 2006. This version contains minor corrections For information write to: Glennis Zilm Ste. 306, 1521 Blackwood St. White Rock, B.C. V4B 3V6 E-mail: [email protected] or Ethel Warbinek 2448 - 124th Street Surrey, B.C. V4A 3N2 E-mail: [email protected] This ms has not been peer reviewed, but a scholarly articles based on this research appeared in Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 1995, Fall, 27 (3), 61-87, and in Canadian Journal of Infection Control, 2002, 17 (2), 35-36, 38-40, 42-43. and a peer-reviewed summary presentation was given at the First Annual Ethel Johns Nursing Research Forum sponsored by the Xi Eta Chapter, Sigma Theta Tau, St. Paul's Hospital Convention Centre, Vancouver, B.C. 3 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Glennis Zilm, BSN, BJ, MA, is a retired registered nurse and a semi-retired freelance writer and editor in the health care fields. She is an honorary professor in the University of British Columbia School of Nursing. -

Volume 12, No.1, Spring 2007

Nikkei Images A Publication of the National Nikkei Museum and Heritage Centre ISSN#1203-9017 Spring 2007, Vol. 12, No. 1 Thomas Kunito Shoyama: My Mentor, My Friend by Dr. Midge Ayukawa Japanese proverb: “Fall down seven the camps, when the Canadian gov- times, get up eight” [Nana-korobi ernment decided to accept nisei in the ya-oki] . Could this have been his life armed forces in 1945, Tom enlisted motto that explains his persistence and trained at boot camp in Brant- and his determination? ford, eventually ending up at S20, the When I was living in Lemon Canadian Army Japanese Language Creek and attending school, the School. Although Tom studied hard, principal was Irene Uchida (later, he was disadvantaged in not having a world-renowned geneticist), who any Japanese language training in his knew Tom well from UBC and Van- youth. Later, after we were dispersed couver NEW CANADIAN days. She east of the Rockies and Japan, and often talked about ‘Mr. Shoyama’ Tom was discharged, he went on and sent copies of the school paper, with his life. The CCF government in LEMON CREEK SCHOLASTIC, Saskatchewan under Tommy Doug- to him. I have a treasured copy of las hired him and Tom’s genius in the April 1944 edition in which Tom economics and dealing with person- wrote a page and a half letter full of nel was finally recognized. He was wise advice to the young. The NC instrumental in bringing medicare to Tom Shoyama on his 88th birthday. was our one and only connection Saskatchewan. (At Tom’s 80th birth- September 24, 2004. -

The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century

“No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century by Kevin Woodger A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Kevin Woodger 2020 “No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century Kevin Woodger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation examines the Canadian Cadet Movement and Boy Scouts Association of Canada, seeking to put Canada’s two largest uniformed youth movements for boys into sustained conversation. It does this in order to analyse the ways in which both movements sought to form masculine national and imperial subjects from their adolescent members. Between the end of the First World War and the late 1960s, the Cadets and Scouts shared a number of ideals that formed the basis of their similar, yet distinct, youth training programs. These ideals included loyalty and service, including military service, to the nation and Empire. The men that scouts and cadets were to grow up to become, as far as their adult leaders envisioned, would be disciplined and law-abiding citizens and workers, who would willingly and happily accept their place in Canadian society. However, these adult-led movements were not always successful in their shared mission of turning boys into their ideal-type of men. The active participation and complicity of their teenaged members, as peer leaders, disciplinary subjects, and as recipients of youth training, was central to their success. -

Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas

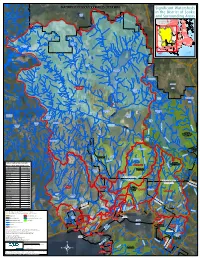

Shawnigan Lake C O W I C H A N V A L L E Y R E G I O N A L D I S T R I C T Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke Grant Lake and Surrounding Areas North C o w i c h a n V a l l e y Saanich R e g i o n a l D i s t r i c t Sidney OCelniptrahl ant Lake Saanich JdFEA H a r o S t r a Highlands it Saanich View Royal Juan de Fuca Langford Electoral Area Oak Bay Esquimalt Jarvis Colwood Victoria Lake Sooke Weeks Lake Metchosin Juan de Fuca Electoral Area ca SpectaFcu le Lake e d it an ra STUDY Ju St AREA Morton Lake Sooke Lake Butchart Lake Devereux Sooke River Lake (Upper) Council Lake Lubbe Wrigglesworth Lake Lake MacDonald Goldstream Lake r Lake e iv R e k o Bear Creek o S Old Wolf Reservoir Boulder Lake Lake Mavis y w Lake H a G d Ranger Butler Lake o a l n d a s Lake Kapoor Regional N C t - r i a s Forslund Park Reserve e g n W a a a o m r l f C r a T Lake r e R e k C i v r W e e e r a k u g h C r e Mount Finlayson e k Sooke Hills Provincial Park Wilderness Regional Park Reserve G o ld s Jack t re a Lake m Tugwell Lake R iv e r W augh Creek Crabapple Lake Goldstream Provincial Park eek Cr S ugh o Wa o Peden k Sooke Potholes e Lake C R Regional Park h i v a e Sheilds Lake r r t e r k e s re C ne i R ary V k M e i v e r e r V C Sooke Hills Table of Significant Watersheds in the e d i t d c Wilderness Regional h o T Charters River C Park Reserve District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas r e e k Watershed Name Area (ha) Sooke Mountain Sooke River (Upper) 27114.93 Boneyard Provincial Park Lake DeMamiel Creek 3985.29 Veitch Creek 2620.78 -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation

Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, and Nanoose First Nation COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: Strathcona Forestry Consulting GIS mapping: Madrone Environmental Services Ltd. November 2010 Strathcona Forestry Consulting pg 1 Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation Lantzville Nanoose Bay Nanoose First Nation Community Wildfire Protection Plan Prepared for: Regional District of Nanaimo Submitted by: Strathcona Forestry Consulting GIS Mapping by: Madrone Environmental Consulting Ltd. November 2010 This Community Wildfire Protection Plan was developed in partnership with: Ministry of Forests and Range Union of British Columbia Municipalities Regional District of Nanaimo Nanoose First Nation Lantzville Fire Rescue District of Lantzville Nanoose Bay Fire Department District of Nanoose Bay CF Maritime Experimental and Test Ranges – Nanoose Range Fire Detachment Administration Preparation: RPF Name (Printed) RPF Signature Date: ___________________ RPF No: _________ Strathcona Forestry Consulting pg 2 Community Wildfire Protection Plan: Lantzville, Nanoose Bay, Nanoose First Nation TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 INTERFACE COMMUNITIES 4 1.2 COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN 7 1.3 LANTZVILLE, NANOOSE BAY, NANOOSE FIRST NATION CWPP 9 2.0 THE SETTING 10 2.1 COMMUNITY PROFILES 10 2.2 LANTZVILLE 11 2.3 NANOOSE BAY 15 2.4 NANOOSE FIRST NATION 18 3.0 BIOPHYSICAL DESCRIPTION 20 3.1 CLIMATE 20 3.2 PHYSIOGRAPHIC FEATURES -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him.