Cellular Iron Metabolism – the IRP/IRE Regulatory Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of the Stability of 70 Housekeeping Genes During Ips Reprogramming Yulia Panina1,2*, Arno Germond1 & Tomonobu M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Analysis of the stability of 70 housekeeping genes during iPS reprogramming Yulia Panina1,2*, Arno Germond1 & Tomonobu M. Watanabe1 Studies on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells highly rely on the investigation of their gene expression which requires normalization by housekeeping genes. Whether the housekeeping genes are stable during the iPS reprogramming, a transition of cell state known to be associated with profound changes, has been overlooked. In this study we analyzed the expression patterns of the most comprehensive list to date of housekeeping genes during iPS reprogramming of a mouse neural stem cell line N31. Our results show that housekeeping genes’ expression fuctuates signifcantly during the iPS reprogramming. Clustering analysis shows that ribosomal genes’ expression is rising, while the expression of cell-specifc genes, such as vimentin (Vim) or elastin (Eln), is decreasing. To ensure the robustness of the obtained data, we performed a correlative analysis of the genes. Overall, all 70 genes analyzed changed the expression more than two-fold during the reprogramming. The scale of this analysis, that takes into account 70 previously known and newly suggested genes, allowed us to choose the most stable of all genes. We highlight the fact of fuctuation of housekeeping genes during iPS reprogramming, and propose that, to ensure robustness of qPCR experiments in iPS cells, housekeeping genes should be used together in combination, and with a prior testing in a specifc line used in each study. We suggest that the longest splice variants of Rpl13a, Rplp1 and Rps18 can be used as a starting point for such initial testing as the most stable candidates. -

Review Article PTEN Gene: a Model for Genetic Diseases in Dermatology

The Scientific World Journal Volume 2012, Article ID 252457, 8 pages The cientificWorldJOURNAL doi:10.1100/2012/252457 Review Article PTEN Gene: A Model for Genetic Diseases in Dermatology Corrado Romano1 and Carmelo Schepis2 1 Unit of Pediatrics and Medical Genetics, I.R.C.C.S. Associazione Oasi Maria Santissima, 94018 Troina, Italy 2 Unit of Dermatology, I.R.C.C.S. Associazione Oasi Maria Santissima, 94018 Troina, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Carmelo Schepis, [email protected] Received 19 October 2011; Accepted 4 January 2012 Academic Editors: G. Vecchio and H. Zitzelsberger Copyright © 2012 C. Romano and C. Schepis. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. PTEN gene is considered one of the most mutated tumor suppressor genes in human cancer, and it’s likely to become the first one in the near future. Since 1997, its involvement in tumor suppression has smoothly increased, up to the current importance. Germline mutations of PTEN cause the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS), which include the past-called Cowden, Bannayan- Riley-Ruvalcaba, Proteus, Proteus-like, and Lhermitte-Duclos syndromes. Somatic mutations of PTEN have been observed in glioblastoma, prostate cancer, and brest cancer cell lines, quoting only the first tissues where the involvement has been proven. The negative regulation of cell interactions with the extracellular matrix could be the way PTEN phosphatase acts as a tumor suppressor. PTEN gene plays an essential role in human development. A recent model sees PTEN function as a stepwise gradation, which can be impaired not only by heterozygous mutations and homozygous losses, but also by other molecular mechanisms, such as transcriptional regression, epigenetic silencing, regulation by microRNAs, posttranslational modification, and aberrant localization. -

Human Phosphatase CDC14A Regulates Actin Organization Through Dephosphorylation of Epithelial Protein Lost in Neoplasm

Human phosphatase CDC14A regulates actin organization through dephosphorylation of epithelial protein lost in neoplasm Nan-Peng Chena,b, Borhan Uddina,b, Robert Hardta, Wen Dinga, Marko Panica,b, Ilaria Lucibelloa, Patricia Kammererc, Thomas Rupperta, and Elmar Schiebela,1 aZentrum für Molekulare Biologie der Universität Heidelberg (ZMBH), Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ)–ZMBH Allianz, Universität Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; bHartmut Hoffmann-Berling International Graduate School of Molecular and Cellular Biology (HBIGS), Universität Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; and cMax Planck Institute of Biochemistry, 82152 Martinsried, Germany Edited by Thomas D. Pollard, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 11, 2017 (received for review November 24, 2016) CDC14 is an essential dual-specificity phosphatase that counteracts Because there have been no systematic attempts to identify CDK1 activity during anaphase to promote mitotic exit in Saccharo- phospho-sites that are regulated by hCDC14A, we know relatively myces cerevisiae. Surprisingly, human CDC14A is not essential for little about the identity of either the proteins that are dephos- cell cycle progression. Instead, it regulates cell migration and cell phorylated by hCDC14A or, indeed, the kinases that counteract adhesion. Little is known about the substrates of hCDC14A and hCDC14A in human cells. The only known substrate of hCDC14A the counteracting kinases. Here, we combine phospho-proteome that acts within the actin cytoskeleton is the protein Kibra (20, 21). profiling and proximity-dependent biotin identification to identify However, considering the broad distribution of hCDC14A hCDC14A substrates. Among these targets were actin regulators, throughout the actin network, it is highly likely that hCDC14A including the tumor suppressor eplin. hCDC14A counteracts EGF- dephosphorylates additional actin-associated proteins. -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

Induction of Micrornas, Mir-155, Mir-222, Mir-424 and Mir-503, Promotes Monocytic Differentiation Through Combinatorial Regulation

Leukemia (2010) 24, 460–466 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/leu ‘ ORIGINAL ARTICLE Induction of microRNAs, mir-155, mir-222, mir-424 and mir-503, promotes monocytic differentiation through combinatorial regulation ARR Forrest1,2, M Kanamori-Katayama1, Y Tomaru1, T Lassmann1, N Ninomiya1, Y Takahashi1, MJL de Hoon1, A Kubosaki1, A Kaiho1, M Suzuki1, J Yasuda1, J Kawai1, Y Hayashizaki1, DA Hume3 and H Suzuki1 1LSA Technology Development Unit, Omics Science Center, RIKEN Yokohama Institute, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan; 2The Eskitis Institute for Cell and Molecular Therapies, Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia and 3The Roslin Institute, Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The University of Edinburgh, Roslin, UK Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) involves a block in terminal that might promote differentiation. MicroRNAs are short 21–22 differentiation of the myeloid lineage and uncontrolled prolif- nucleotide RNA molecules that cause translational repression eration of a progenitor state. Using phorbol myristate acetate and degradation of multiple mRNAs by binding target sequences (PMA), it is possible to overcome this block in THP-1 cells 0 5 (an M5-AML containing the MLL-MLLT3 fusion), resulting in in their 3 UTRs. Multiple microRNAs are implicated in differentiation to an adherent monocytic phenotype. As part of differentiation of cell lineages including skeletal muscle, FANTOM4, we used microarrays to identify 23 microRNAs that adipocytes and neurons6–8 and in mammals, the microRNA are regulated by PMA. We identify four PMA-induced micro- subsystem is essential for embryonic development. Dicer RNAs (mir-155, mir-222, mir-424 and mir-503) that when over- is required for differentiation of embryonic stem cells,9 Dicer expressed cause cell-cycle arrest and partial differentiation and (À/À) knockouts are embryonic lethal10 and Ago2 (À/À) when used in combination induce additional changes not seen 11 by any individual microRNA. -

Human Phosphatase CDC14A Is Recruited to the Cell Leading Edge to Regulate Cell Migration and Adhesion

Human phosphatase CDC14A is recruited to the cell leading edge to regulate cell migration and adhesion Nan-Peng Chena,b, Borhan Uddina,b, Renate Voitc, and Elmar Schiebela,1 aZentrum für Molekulare Biologie der Universität Heidelberg (ZMBH), Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ)-Zentrum für Molekulare Biologie (ZMBH) Allianz, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; bHartmut Hoffmann-Berling International Graduate School of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Universität Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; and cMolecular Biology of the Cell II, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), 69120 Heidelberg, Germany Edited by James E. Cleaver, University of California, San Francisco, CA, and approved December 17, 2015 (received for review August 6, 2015) Cell adhesion and migration are highly dynamic biological pro- With mitotic exit, the proteins that were phosphorylated by cesses that play important roles in organ development and CDK1 are dephosphorylated, so that cells can return to the cancer metastasis. Their tight regulation by small GTPases and nonmitotic, interphase status (13). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, protein phosphorylation make interrogation of these key pro- cell-division cycle 14 (Cdc14) is the major phosphatase that cesses of great importance. We now show that the conserved dual- counteracts Cdk1 activity after the metaphase–anaphase transi- specificity phosphatase human cell-division cycle 14A (hCDC14A) tion (14). The function of Cdc14 in budding yeast has been well associates with the actin cytoskeleton of human cells. To un- studied and two regulatory networks have been identified that derstand hCDC14A function at this location, we manipulated native promote the release of Cdc14 from the RENT complex in the PD loci to ablate hCDC14A phosphatase activity (hCDC14A )inun- nucleolus: “Cdc Fourteen Early Anaphase Release” (FEAR) and transformed hTERT-RPE1 and colorectal cancer (HCT116) cell lines “Mitotic Exit Network” (MEN) (15–17). -

Live-Cell Imaging Rnai Screen Identifies PP2A–B55α and Importin-Β1 As Key Mitotic Exit Regulators in Human Cells

LETTERS Live-cell imaging RNAi screen identifies PP2A–B55α and importin-β1 as key mitotic exit regulators in human cells Michael H. A. Schmitz1,2,3, Michael Held1,2, Veerle Janssens4, James R. A. Hutchins5, Otto Hudecz6, Elitsa Ivanova4, Jozef Goris4, Laura Trinkle-Mulcahy7, Angus I. Lamond8, Ina Poser9, Anthony A. Hyman9, Karl Mechtler5,6, Jan-Michael Peters5 and Daniel W. Gerlich1,2,10 When vertebrate cells exit mitosis various cellular structures can contribute to Cdk1 substrate dephosphorylation during vertebrate are re-organized to build functional interphase cells1. This mitotic exit, whereas Ca2+-triggered mitotic exit in cytostatic-factor- depends on Cdk1 (cyclin dependent kinase 1) inactivation arrested egg extracts depends on calcineurin12,13. Early genetic studies in and subsequent dephosphorylation of its substrates2–4. Drosophila melanogaster 14,15 and Aspergillus nidulans16 reported defects Members of the protein phosphatase 1 and 2A (PP1 and in late mitosis of PP1 and PP2A mutants. However, the assays used in PP2A) families can dephosphorylate Cdk1 substrates in these studies were not specific for mitotic exit because they scored pro- biochemical extracts during mitotic exit5,6, but how this relates metaphase arrest or anaphase chromosome bridges, which can result to postmitotic reassembly of interphase structures in intact from defects in early mitosis. cells is not known. Here, we use a live-cell imaging assay and Intracellular targeting of Ser/Thr phosphatase complexes to specific RNAi knockdown to screen a genome-wide library of protein substrates is mediated by a diverse range of regulatory and targeting phosphatases for mitotic exit functions in human cells. We subunits that associate with a small group of catalytic subunits3,4,17. -

The Anaphase Promoting Complex Impacts Repair Choice by Protecting Ubiquitin Signalling at DNA Damage Sites

ARTICLE Received 13 Oct 2016 | Accepted 25 Apr 2017 | Published 12 Jun 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15751 OPEN The anaphase promoting complex impacts repair choice by protecting ubiquitin signalling at DNA damage sites Kyungsoo Ha1,2,3,*, Chengxian Ma4,*, Han Lin3, Lichun Tang1,2, Zhusheng Lian5, Fang Zhao6, Ju-Mei Li7, Bei Zhen1,2, Huadong Pei1,2, Suxia Han5, Marcos Malumbres8, Jianping Jin7, Huan Chen1,2, Yongxiang Zhao6, Qing Zhu4 & Pumin Zhang1,2,3 Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are repaired through two major pathways, homology-directed recombination (HDR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). While HDR can only occur in S/G2, NHEJ can happen in all cell cycle phases (except mitosis). How then is the repair choice made in S/G2 cells? Here we provide evidence demonstrating that APCCdh1 plays a critical role in choosing the repair pathways in S/G2 cells. Our results suggest that the default for all DSBs is to recruit 53BP1 and RIF1. BRCA1 is blocked from being recruited to broken ends because its recruitment signal, K63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains on histones, is actively destroyed by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP1. We show that the removal of USP1 depends on APCCdh1 and requires Chk1 activation known to be catalysed by ssDNA-RPA-ATR sig- nalling at the ends designated for HDR, linking the status of end processing to RIF1 or BRCA1 recruitment. 1 National Center for Protein Sciences Beijing, Life Sciences Park, Beijing 102206, China. 2 State Key Laboratory of Proteomics, Beijing Proteome Research Center, Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine, 27 Taiping Road, Beijing 100850, China. -

Expression Profile of Tyrosine Phosphatases in HER2 Breast

Cellular Oncology 32 (2010) 361–372 361 DOI 10.3233/CLO-2010-0520 IOS Press Expression profile of tyrosine phosphatases in HER2 breast cancer cells and tumors Maria Antonietta Lucci a, Rosaria Orlandi b, Tiziana Triulzi b, Elda Tagliabue b, Andrea Balsari c and Emma Villa-Moruzzi a,∗ a Department of Experimental Pathology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy b Molecular Biology Unit, Department of Experimental Oncology, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milan, Italy c Department of Human Morphology and Biomedical Sciences, University of Milan, Milan, Italy Abstract. Background: HER2-overexpression promotes malignancy by modulating signalling molecules, which include PTPs/DSPs (protein tyrosine and dual-specificity phosphatases). Our aim was to identify PTPs/DSPs displaying HER2-associated expression alterations. Methods: HER2 activity was modulated in MDA-MB-453 cells and PTPs/DSPs expression was analysed with a DNA oligoar- ray, by RT-PCR and immunoblotting. Two public breast tumor datasets were analysed to identify PTPs/DSPs differentially ex- pressed in HER2-positive tumors. Results: In cells (1) HER2-inhibition up-regulated 4 PTPs (PTPRA, PTPRK, PTPN11, PTPN18) and 11 DSPs (7 MKPs [MAP Kinase Phosphatases], 2 PTP4, 2 MTMRs [Myotubularin related phosphatases]) and down-regulated 7 DSPs (2 MKPs, 2 MTMRs, CDKN3, PTEN, CDC25C); (2) HER2-activation with EGF affected 10 DSPs (5 MKPs, 2 MTMRs, PTP4A1, CDKN3, CDC25B) and PTPN13; 8 DSPs were found in both groups. Furthermore, 7 PTPs/DSPs displayed also altered protein level. Analysis of 2 breast cancer datasets identified 6 differentially expressed DSPs: DUSP6, strongly up-regulated in both datasets; DUSP10 and CDC25B, up-regulated; PTP4A2, CDC14A and MTMR11 down-regulated in one dataset. -

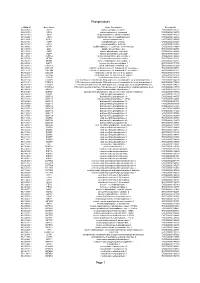

Phosphatases Page 1

Phosphatases esiRNA ID Gene Name Gene Description Ensembl ID HU-05948-1 ACP1 acid phosphatase 1, soluble ENSG00000143727 HU-01870-1 ACP2 acid phosphatase 2, lysosomal ENSG00000134575 HU-05292-1 ACP5 acid phosphatase 5, tartrate resistant ENSG00000102575 HU-02655-1 ACP6 acid phosphatase 6, lysophosphatidic ENSG00000162836 HU-13465-1 ACPL2 acid phosphatase-like 2 ENSG00000155893 HU-06716-1 ACPP acid phosphatase, prostate ENSG00000014257 HU-15218-1 ACPT acid phosphatase, testicular ENSG00000142513 HU-09496-1 ACYP1 acylphosphatase 1, erythrocyte (common) type ENSG00000119640 HU-04746-1 ALPL alkaline phosphatase, liver ENSG00000162551 HU-14729-1 ALPP alkaline phosphatase, placental ENSG00000163283 HU-14729-1 ALPP alkaline phosphatase, placental ENSG00000163283 HU-14729-1 ALPPL2 alkaline phosphatase, placental-like 2 ENSG00000163286 HU-07767-1 BPGM 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate mutase ENSG00000172331 HU-06476-1 BPNT1 3'(2'), 5'-bisphosphate nucleotidase 1 ENSG00000162813 HU-09086-1 CANT1 calcium activated nucleotidase 1 ENSG00000171302 HU-03115-1 CCDC155 coiled-coil domain containing 155 ENSG00000161609 HU-09022-1 CDC14A CDC14 cell division cycle 14 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) ENSG00000079335 HU-11533-1 CDC14B CDC14 cell division cycle 14 homolog B (S. cerevisiae) ENSG00000081377 HU-06323-1 CDC25A cell division cycle 25 homolog A (S. pombe) ENSG00000164045 HU-07288-1 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) ENSG00000101224 HU-06033-1 CDKN3 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 ENSG00000100526 HU-02274-1 CTDSP1 CTD (carboxy-terminal domain, -

Dynamics of Dual Specificity Phosphatases and Their Interplay with Protein Kinases in Immune Signaling Yashwanth Subbannayya1,2, Sneha M

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/568576; this version posted March 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Dynamics of dual specificity phosphatases and their interplay with protein kinases in immune signaling Yashwanth Subbannayya1,2, Sneha M. Pinto1,2, Korbinian Bösl1, T. S. Keshava Prasad2 and Richard K. Kandasamy1,3,* 1Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research (CEMIR), and Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine (IKOM), Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2Center for Systems Biology and Molecular Medicine, Yenepoya (Deemed to be University), Mangalore 575018, India 3Centre for Molecular Medicine Norway (NCMM), Nordic EMBL Partnership, University of Oslo and Oslo University Hospital, N-0349 Oslo, Norway *Correspondence: Richard K. Kandasamy ([email protected]) Abstract Dual specificity phosphatases (DUSPs) have a well-known role as regulators of the immune response through the modulation of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs). Yet the precise interplay between the various members of the DUSP family with protein kinases is not well understood. Recent multi-omics studies characterizing the transcriptomes and proteomes of immune cells have provided snapshots of molecular mechanisms underlying innate immune response in unprecedented detail. In this study, we focused on deciphering the interplay between members of the DUSP family with protein kinases in immune cells using publicly available omics datasets. Our analysis resulted in the identification of potential DUSP- mediated hub proteins including MAPK7, MAPK8, AURKA, and IGF1R. Furthermore, we analyzed the association of DUSP expression with TLR4 signaling and identified VEGF, FGFR and SCF-KIT pathway modules to be regulated by the activation of TLR4 signaling. -

The Cdc14b-Cdh1-Plk1 Axis Controls the G2 DNA-Damage-Response Checkpoint

The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 Axis Controls the G2 DNA-Damage-Response Checkpoint Florian Bassermann,1 David Frescas,1 Daniele Guardavaccaro,1 Luca Busino,1 Angelo Peschiaroli,1 and Michele Pagano1,2,* 1Department of Pathology, NYU Cancer Institute, New York University School of Medicine, 550 First Avenue, MSB 599, New York, NY 10016, USA 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute, 550 First Avenue, MSB 599, New York, NY 10016, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.043 SUMMARY dent phosphorylation of Cdh1 and the presence of Emi1. In early mitosis, Emi1 is eliminated via the SCFbTrcp ubiquitin ligase, but In response to DNA damage in G2, mammalian cells the bulk of APC/CCdh1 remains inactive due to high Cdk1 activity. must avoid entry into mitosis and instead initiate DNA Ultimately, Cdh1 activation in anaphase involves Cdk1 inactiva- repair. Here, we show that, in response to genotoxic tion by APC/CCdc20 and Cdh1 dephosphorylation. In yeast, this stress in G2, the phosphatase Cdc14B translocates dephosphorylation is carried out by the Cdc14 phosphatase, from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm and induces but the mechanism in mammals remains unclear (D’Amours the activation of the ubiquitin ligase APC/CCdh1, and Amon, 2004; Sullivan and Morgan, 2007). Upon DNA damage, proliferating cells activate a regulatory with the consequent degradation of Plk1, a prominent signaling network to either arrest the cell cycle and enable DNA mitotic kinase. This process induces the stabilization repair or, if the DNA damage is too extensive to be repaired, in- of Claspin, an activator of the DNA-damage check- duce apoptosis (Bartek and Lukas, 2007; Harper and Elledge, point, and Wee1, an inhibitor of cell-cycle progres- 2007; Kastan and Bartek, 2004).