Use of Parecoxib by Continuous Subcutaneous Infusion for Cancer Pain in a Hospice Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerging Drug List PARECOXIB SODIUM

Emerging Drug List PARECOXIB SODIUM NO. 10 MAY 2001 Generic (Trade Name): Parecoxib sodium Manufacturer: Pharmacia & Upjohn Inc. Indication: For peri-operative pain relief Current Regulatory Parecoxib is currently under review at Health Canada and the Food and Drug Status: Administration in the U.S. They are expecting approval in the fourth quarter of 2001. It is not marketed in any country at this time Description: Parecoxib is the first parenteral cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitor to be developed. It is a water-soluble prodrug that is rapidly hydrolyzed to valdecoxib (the active COX-2 inhibitor). Valdecoxib's affinity for COX-2 versus COX-1 is 90 times greater than celecoxib and 34,000 times greater than ketorolac. Once injected, peak concentrations of valdecoxib are attained in 10 to 20 minutes. Valdecoxib has a half-life of eight to 10 hours. Current Treatment: Currently, the only other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent that is available as an injection is ketorolac. Ketorolac is used in some centres for peri-operative pain management, however opioids are the main class of agents used for this indication. Ketorolac has been associated with a relatively high incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, including severe cases of hemorrhage. Cost: There is no information available on the cost of parecoxib. Evidence: Parecoxib has been compared to ketorolac and morphine in clinical trials. Parecoxib at a dose of 20 and 40 mg/day IV, were compared to ketorolac, 30 mg/day IV and morphine, 4 mg/day or placebo in 202 women undergoing hysterectomy. Both doses of parecoxib were comparable to ketorolac for relieving postoperative pain. -

Efficacy and Safety of Postoperative Intravenous Parecoxib Sodium

Open Access Protocol BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011732 on 8 September 2016. Downloaded from Efficacy and safety of Postoperative Intravenous Parecoxib sodium Followed by ORal CElecoxib (PIPFORCE) post- total knee arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis: a study protocol for a multicentre, double-blind, parallel- group trial Qianyu Zhuang,1 Yanyan Bian,1 Wei Wang,1 Jingmei Jiang,2 Bin Feng,1 Tiezheng Sun,3 Jianhao Lin,3 Miaofeng Zhang,4 Shigui Yan,4 Bin Shen,5 Fuxing Pei,5 Xisheng Weng1 To cite: Zhuang Q, Bian Y, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Wang W, et al. Efficacy and Introduction: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been safety of Postoperative regarded as a most painful orthopaedic surgery. ▪ Intravenous Parecoxib This is the first study to investigate the efficacy Although many surgeons sequentially use parecoxib sodium Followed by ORal and safety of the sequential analgesia regimen of CElecoxib (PIPFORCE) post- and celecoxib as a routine strategy for postoperative intravenous parecoxib followed by oral celecoxib total knee arthroplasty in pain control after TKA, high quality evidence is still after total knee arthroplasty surgery. patients with osteoarthritis: a lacking to prove the effect of this sequential regimen, ▪ This study will explore the benefits of prolonged study protocol for a especially at the medium-term follow-up. The purpose sequential treatment of parecoxib and celecoxib multicentre, double-blind, of this study, therefore, is to evaluate efficacy and in medium-term function recovery. parallel-group trial. BMJ safety of postoperative intravenous parecoxib sodium ▪ The results will promote the non-steroidal Open 2016;6:e011732. -

Safety of Etoricoxib in Patients with Reactions to Nsaids

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Safety of Etoricoxib in Patients With Reactions to NSAIDs O Quercia, F Emiliani, FG Foschi, GF Stefanini Allergology High Specialty Unit, General Medicine, Faenza Hospital, AUSL Ravenna, Italy ■ Abstract Background: Adverse reactions to nonsteroidal anti-infl ammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a frequently reported problem due to the fact that these molecules are often used for control of pain and infl ammation. Although the use of selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (COX) 2 helps to prevent some of these adverse reactions, they can have cardiac side effects when taken for prolonged periods. Here we report the safety and tolerability of etoricoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor with fewer cardiovascular effects, in patients with adverse reactions to NSAIDs. Patients and methods: We performed placebo-controlled oral challenge with etoricoxib in 65 patients with previous adverse reactions to NSAIDs: 13 to salicylates, 18 to arylpropionic acids, 10 to arylacetic acid, 12 to oxicam and derivates, 8 to pyrazolones, and 4 to acetaminophen (paracetamol). The reported symptoms were urticaria or angioedema in 69%, rhinitis in 3%, and 1 case of anaphylactic shock (1.5%). The challenge was done using the placebo on the fi rst day, half dosage of etoricoxib (45 mg) on the second day, and the therapeutic dose of 90 mg on the third day. The challenge was done in the outpatient department of the hospital and the subjects were monitored for a further 4 to 6 hours after challenge. Results: Oral challenge with etoricoxib was well tolerated in 97% of the patients. Only 2 systemic reactions were reported during the challenge test. -

Use of Parecoxib by Continuous Subcutaneous Infusion for Cancer Pain in a Hospice Population

BMJ Support Palliat Care: first published as 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001348 on 1 September 2017. Downloaded from Short report Use of parecoxib by continuous subcutaneous infusion for cancer pain in a hospice population Peter Armstrong,1 Pauline Wilkinson,2 Noleen K McCorry3 1Pharmacy Department, Belfast ABSTRACT adverse effects.2 Parecoxib, a prodrug Health and Social Care Trust, Objectives To characterise the use of the of valdecoxib, is an injectable selective Belfast, UK 2Consultant in Palliative parenteral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory COX-2 inhibitor marketed in the UK as Medicine, Marie Curie Hospice, drug parecoxib when given by continuous Dynastat Injection by Pfizer Limited. It Belfast, UK subcutaneous infusion (CSCI) in a hospice is licensed for the short-term treatment 3 Centre of Excellence for Public population. Clinical experience suggests of postoperative pain in adults by the Health (NI), Queen’s University 3 Belfast, Belfast, UK parecoxib CSCI may be of benefit in this intramuscular or intravenous routes. It population, but empirical evidence in relation to has been used extensively by continuous Correspondence to its safety and efficacy is lacking. subcutaneous infusion (CSCI) in pallia- Mr. Peter Armstrong; Methods Retrospective chart review of patients peter. armstrong@ belfasttrust. tive care in Northern Ireland; however, hscni. net with a cancer diagnosis receiving parecoxib CSCI evidence for its safety and efficacy by this from 2008 to 2013 at the Marie Curie Hospice, route is lacking. Received 3 March 2017 Belfast. Data were collected on treatment Revised 9 August 2017 Accepted 16 August 2017 regime, tolerability and, in patients receiving AIM OF THE STUDY at least 7 days treatment, baseline opioid dose This study aims to: and changes in pain scores or opioid rescue 1. -

Parecoxib Increases Blood Pressure Through Inhibition Of

REVISTA DE INVESTIGACIÓN CLÍNICA Contents available at PubMed www.clinicalandtranslationalinvestigation.com PERMANYER www.permanyer.com Rev Inves Clin. 2015;67:250-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Parecoxib Increases Blood Pressure Through Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Messenger RNA in an Experimental Model © Permanyer Publications 2015 .rehsilbup eht fo noissimrep nettirw roirp eht tuohtiw gniypocotohp ro decudorper eb yam noitacilbup siht fo trap oN trap fo siht noitacilbup yam eb decudorper ro Ángel Antoniogniypocotohp Vértiz-Hernándeztuohtiw eht 1 *, Flavioroirp Martínez-Moralesnettirw 2, Roberto noissimrep Valle-Aguilera fo eht 2, .rehsilbup Pedro López-Sánchez3, Rafael Villalobos-Molina4 and José Pérez-Urizar5 1Coordinación Académica Región Altiplano, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Matehuala, S.L.P., México; 2Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, S.L.P., México; 3School of Medicine, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México, D.F., México; 4Faculty of Chemical Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, S.L.P., México; 5Faculty of Advanced Studies-Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Tlalnepantla, Edo. de México, México ABSTRACT Background: Cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors have been developed to alleviate pain and inflammation; however, the use of a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor is associated with mild edema, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk. Aim: To evaluate, in an experimental model in normotensive rats, the effect of treatment with parecoxib in comparison with diclofenac and aspirin and L-NAME, a non-selective nitric oxide synthetase, on mean arterial blood pressure, and cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 messenger RNA and protein expression in aortic tissue. Methods: Rats were treated for seven days with parecoxib (10 mg/kg/day), diclofenac (3.2 mg/kg/day), aspirin (10 mg/kg/day), or L-NAME (10 mg/kg/day). -

Non Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Non Steroidal Anti‐inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) 4 signs of inflammation • Redness ‐ due to local vessel dilatation • Heat ‐ due to local vessel dilatation • Swelling – due to influx of plasma proteins and phagocytic cells into the tissue spaces • Pain – due to local release of enzymes and increased tissue pressure NSAIDs • Cause relief of pain ‐. analgesic • Suppress the signs and symptoms of inflammation. • Exert antipyretic action. • Useful in pain related to inflammation. Esp for superficial/integumental pain . Classification of NSAIDs • Salicylates: aspirin, Sodium salicylate & diflunisal. • Propionic acid derivatives: ibuprofen, ketoprofen, naproxen. • Aryl acetic acid derivatives: diclofenac, ketorolac • Indole derivatives: indomethacin, sulindac • Alkanones: Nabumetone. • Oxicams: piroxicam, tenoxicam Classification of NSAIDs ….. • Anthranilic acid derivatives (fenamates): mefenamic acid and flufenamic acid. • Pyrazolone derivatives: phenylbutazone, oxyphenbutazone, azapropazone (apazone) & dipyrone (novalgine). • Aniline derivatives (analgesic only): paracetamol. Clinical Classif. • Non selective Irreversible COX inhibitors • Non slective Reversible COX inhibitors • Preferential COX 2 inhibitors • 10‐20 fold cox 2 selective • meloxicam, etodolac, nabumetone • Selective COX 2 inhibitors • > 50 fold COX ‐2 selective • Celecoxib, Etoricoxib, Rofecoxib, Valdecoxib • COX 3 Inhibitor? PCM Cyclooxygenase‐1 (COX‐1): -constitutively expressed in wide variety of cells all over the body. -"housekeeping enzyme" -ex. gastric cytoprotection, hemostasis Cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2): -inducible enzyme -dramatically up-regulated during inflammation (10-18X) -constitutive : maintains renal blood flow and renal electrolyte homeostasis Salicylates Acetyl salicylic acid (aspirin). Kinetics: • Well absorbed from the stomach, more from upper small intestine. • Distributed all over the body, 50‐80% bound to plasma protein (albumin). • Metabolized to acetic acid and salicylates (active metabolite). • Salicylate is conjugated with glucuronic acid and glycine. • Excreted by the kidney. -

Clinical Pharmacology of Novel Selective COX-2 Inhibitors

Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2004, 10, 0000-0000 1 Clinical Pharmacology of Novel Selective COX-2 Inhibitors S. Tacconelli, M. L. Capone and P. Patrignani* Department of Medicine and Center of Excellence on Aging, “G. d’Annunzio” University, Chieti, Italy Abstract: Novel coxibs (i.e. etoricoxib, valdecoxib, parecoxib and lumiracoxib) with enhanced biochemical cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 selectivity over that of rofecoxib and celecoxib have been recently developed. They have the potential advantage to spare COX-1 activity, thus reducing gastrointestinal toxicity, even when administered at high doses to improve efficacy. They are characterized by different pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetics features. The higher biochemical selectivity of valdecoxib than celecoxib, evidenced in vitro, may be clinically relevant leading to an improved gastrointestinal safety. Interestingly, parecoxib, a pro-drug of valdecoxib, is the only injectable coxib. Etoricoxib shows only a slightly improved COX-2 selectivity than rofecoxib, a highly selective COX-2 inhibitor that has been reported to halve the incidence of serious gastrointestinal toxicity compared to nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Lumiracoxib, the most selective COX-2 inhibitor in vitro, is the only acidic coxib. The hypothesis that this chemical property may lead to an increased and persistent drug accumulation in inflammatory sites and consequently to an improved clinical efficacy, however, remains to be verified. Several randomized clinical studies suggest that the novel coxibs have comparable efficacy to nonselective NSAIDs in the treatment of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and acute pain, but they share similar renal side-effects. The apparent dose-dependence of renal toxicity may limit the use of higher doses of the novel coxibs for improved efficacy. -

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of - Medicines belonging to the ATC group M01 (Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 6 DISCLAIMER 8 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 9 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Phenylbutazone (ATC: M01AA01) 11 Mofebutazone (ATC: M01AA02) 17 Oxyphenbutazone (ATC: M01AA03) 18 Clofezone (ATC: M01AA05) 19 Kebuzone (ATC: M01AA06) 20 Indometacin (ATC: M01AB01) 21 Sulindac (ATC: M01AB02) 25 Tolmetin (ATC: M01AB03) 30 Zomepirac (ATC: M01AB04) 33 Diclofenac (ATC: M01AB05) 34 Alclofenac (ATC: M01AB06) 39 Bumadizone (ATC: M01AB07) 40 Etodolac (ATC: M01AB08) 41 Lonazolac (ATC: M01AB09) 45 Fentiazac (ATC: M01AB10) 46 Acemetacin (ATC: M01AB11) 48 Difenpiramide (ATC: M01AB12) 53 Oxametacin (ATC: M01AB13) 54 Proglumetacin (ATC: M01AB14) 55 Ketorolac (ATC: M01AB15) 57 Aceclofenac (ATC: M01AB16) 63 Bufexamac (ATC: M01AB17) 67 2 Indometacin, Combinations (ATC: M01AB51) 68 Diclofenac, Combinations (ATC: M01AB55) 69 Piroxicam (ATC: M01AC01) 73 Tenoxicam (ATC: M01AC02) 77 Droxicam (ATC: M01AC04) 82 Lornoxicam (ATC: M01AC05) 83 Meloxicam (ATC: M01AC06) 87 Meloxicam, Combinations (ATC: M01AC56) 91 Ibuprofen (ATC: M01AE01) 92 Naproxen (ATC: M01AE02) 98 Ketoprofen (ATC: M01AE03) 104 Fenoprofen (ATC: M01AE04) 109 Fenbufen (ATC: M01AE05) 112 Benoxaprofen (ATC: M01AE06) 113 Suprofen (ATC: M01AE07) 114 Pirprofen (ATC: M01AE08) 115 Flurbiprofen (ATC: M01AE09) 116 Indoprofen (ATC: M01AE10) 120 Tiaprofenic Acid (ATC: -

Defined Daily Dose and Appropriateness of Clinical

pharmacy Article Defined Daily Dose and Appropriateness of Clinical Application: The Coxibs and Traditional Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Postoperative Orthopaedics Pain Control in a Private Hospital in Malaysia Faizah Safina Bakrin 1,* , Mohd Makmor-Bakry 2, Wan Hazmy Che Hon 3,4, Shafeeq Mohd Faizal 4, Mohamed Mansor Manan 5 and Long Chiau Ming 6 1 School of Pharmacy, KPJ Healthcare University College, Nilai 71800, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia 2 Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Kebangsaaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur 50300, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 School of Medicine, KPJ Healthcare University College, Nilai 71800, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 KPJ Seremban Specialist Hospital, Seremban 70200, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; [email protected] 5 Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Puncak Alam 42300, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 6 PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Gadong BE1410, Brunei; [email protected] * Correspondence: faizasafi[email protected]; Tel.: +606-794-2630 Received: 18 September 2020; Accepted: 3 December 2020; Published: 8 December 2020 Abstract: Introduction: Drug utilization of analgesics in a private healthcare setting is useful to examine their prescribing patterns, especially the newer injectable cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors (coxibs). Objectives: To evaluate the utilization of coxibs and traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (tNSAIDs) indicated for postoperative orthopaedic pain control using defined daily dose (DDD) and ratio of use density to use rate (UD/UR). Method: A retrospective drug utilization review (DUR) of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at an inpatient department of a private teaching hospital in Seremban, Malaysia was conducted. Patients’ demographic characteristics, medications prescribed, clinical lab results, visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores and length of hospital stay were documented. -

Parecoxib (As Sodium)

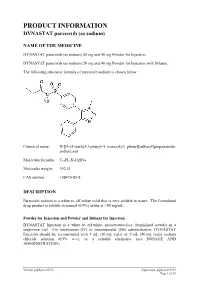

PRODUCT INFORMATION DYNASTAT parecoxib (as sodium) NAME OF THE MEDICINE DYNASTAT parecoxib (as sodium) 20 mg and 40 mg Powder for Injection. DYNASTAT parecoxib (as sodium) 20 mg and 40 mg Powder for Injection with Diluent. The following structural formula of parecoxib sodium is shown below: Chemical name: N-[[4-(5-methyl-3-phenyl-4 isoxazolyl) phenyl]sulfonyl]propanamide, sodium salt Molecular formula: C19H17N2O4SNa Molecular weight: 392.41 CAS number: 198470-85-8 DESCRIPTION Parecoxib sodium is a white to off-white solid that is very soluble in water. The formulated drug product is soluble in normal (0.9%) saline at >50 mg/mL. Powder for Injection and Powder and Diluent for Injection DYNASTAT Injection is a white to off-white, preservative-free, lyophilised powder in a single-use vial. For intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) administration, DYNASTAT Injection should be reconstituted with 1 mL (20 mg vials) or 2 mL (40 mg vials) sodium chloride solution (0.9% w/v), or a suitable alternative (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Version: pfpdynav10213 Supersedes: pfpdynav10912 Page 1 of 25 Diluent for Injection DYNASTAT Injection may be supplied with a 2 mL capacity diluent ampoule with a fill volume of either 1 mL or 2 mL Sodium Chloride Intravenous Infusion (0.9% w/v) BP. Reconstituted Solution The reconstituted solution is clear and colourless. DYNASTAT Injection 20 mg and 40 mg contains parecoxib sodium, sodium phosphate-dibasic anhydrous; phosphoric acid and/or sodium hydroxide may have been added to adjust pH. When reconstituted in sodium chloride solution (0.9% w/v), DYNASTAT Injection contains approximately 0.22 mEq and 0.44 mEq of sodium per 20 mg vial and 40 mg vial, respectively. -

Dynastat, INN-Parecoxib

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Dynastat 40 mg powder for solution for injection 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each vial contains 40 mg parecoxib (as 42.36 mg parecoxib sodium). After reconstitution, the concentration of parecoxib is 20 mg/ml. Each 2 ml of reconstituted powder contains 40 mg of parecoxib. Excipient with known effect This medicinal product contains less than 1 mmol sodium (23 mg) per dose. When reconstituted in sodium chloride 9 mg/ml (0.9%) solution, Dynastat contains approximately 0.44 mmol of sodium per vial. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder for solution for injection (powder for injection). White to off-white powder. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications For the short-term treatment of postoperative pain in adults. The decision to prescribe a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor should be based on an assessment of the individual patient's overall risks (see sections 4.3 and 4.4). 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology The recommended dose is 40 mg administered intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM), followed every 6 to 12 hours by 20 mg or 40 mg as required, not to exceed 80 mg/day. As the cardiovascular risk of COX-2 specific inhibitors may increase with dose and duration of exposure, the shortest duration possible and the lowest effective daily dose should be used. There is limited clinical experience with Dynastat treatment beyond three days (see section 5.1). Concomitant use with opioid analgesics Opioid analgesics can be used concurrently with parecoxib, dosing as described in the paragraph above. -

Is Ketorolac Safe for Use After Cardiac Surgery?

Black Box Warning: Is Ketorolac Safe for Use After Cardiac Surgery? Lisa Oliveri, BSc,*† Katie Jerzewski, BSc,*† and Alexander Kulik, MD, MPH*† Objective: In 2005, after the identification of cardiovascu- similar to those expected using Society of Thoracic Surgery lar safety concerns with the use of nonsteroidal anti- database risk-adjusted outcomes. In unadjusted analysis, inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the FDA issued a black box patients who received ketorolac had similar or better post- warning recommending against the use of NSAIDs following operative outcomes compared with patients who did not cardiac surgery. The goal of this study was to assess the receive ketorolac, including gastrointestinal bleeding (1.2% v postoperative safety of ketorolac, an intravenously admin- 1.3%; p ¼ 1.0), renal failure requiring dialysis (0.4% v 3.0%; istered NSAID, after cardiac surgery. p ¼ 0.001), perioperative myocardial infarction (1.0% v 0.6%; Design: Retrospective observational study. p ¼ 0.51), stroke or transient ischemic attack (1.0% v 1.7%; Setting: Single center, regional hospital. p ¼ 0.47), and death (0.4% v 5.8%; p o 0.0001). With adjust- Participants: A total of 1,309 cardiac surgical patients ment in a multivariate model, treatment with ketorolac was (78.1% coronary bypass, 28.0% valve) treated between 2006 not a predictor for adverse outcome in this cohort (odds and 2012. ratio: 0.72; p ¼ 0.23). Interventions: A total of 488 of these patients received Conclusions: Ketorolac appears to be well-tolerated for ketorolac for postoperative analgesia within 72 hours of use when administered selectively after cardiac surgery.