Integrating Missile Defense and Conventional Weapons in US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winning the Salvo Competition Rebalancing America’S Air and Missile Defenses

WINNING THE SALVO COMPETITION REBALANCING AMERICA’S AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSES MARK GUNZINGER BRYAN CLARK WINNING THE SALVO COMPETITION REBALANCING AMERICA’S AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSES MARK GUNZINGER BRYAN CLARK 2016 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2016 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Gunzinger is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Mr. Gunzinger has served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces Transformation and Resources. A retired Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot, he joined the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 2004. Mark was appointed to the Senior Executive Service and served as Principal Director of the Department’s central staff for the 2005–2006 Quadrennial Defense Review. Following the QDR, he served as Director for Defense Transformation, Force Planning and Resources on the National Security Council staff. Mr. Gunzinger holds an M.S. in National Security Strategy from the National War College, a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, a Master of Public Administration from Central Michigan University, and a B.S. in chemistry from the United States Air Force Academy. -

Jane's Online Browsing

Log In Log Out Help Feedback My Account Jane's Services Online Research Online Channels Data Search | Data Browse | Image Search | Web Search | News/Analysis 12 Images DEFENSIVE WEAPONS, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Date Posted: 24 April 2002 Jane's Strategic Weapon Systems 37 RIM-66/-67/-156 Standard SM-1/-2 and Standard SM-3 Type Short- and medium-range, ship-based, solid-propellant, theatre defence missiles. Development The RIM-66 Standard missile was developed in the 1960s as a replacement for the RIM-24A Tartar surface-to-air missile for the US Navy. The incremental improvement of this system has continued for over 30 years, with Standard missile versions from RIM-66A to -66M. RIM-66 Standard versions are known as SM-1MR and SM-2MR (medium range); the principal differences between the earlier SM-1MR (RIM-66A/B/E) and SM-2MR (RIM-66C/D/G/H/J/K/L/M) missiles were that the SM-2 incorporated an inertial guidance system and updated the conical scan semi-active radar terminal guidance to a monopulse semi-active radar. A surface-to-surface anti-radar homing version of SM-1MR (RGM-66D) was developed in the early 1970s and the air-launched variant of this, the AGM-78 Standard, is believed to still be in service with the US Navy. SM-1 missiles are single-stage and present build standards are block 6, 6A and 6B. SM-2 single-stage missiles are known as Tartar or Aegis categories, with present build standards block 2, 3, 3A and 3B. -

Tactical References for Falcon 4.0

Tactical Reference for Falcon 4.0 1 Tactical References for Falcon 4.0 Tactical Reference Munitions Handbook 2 Tactical Reference for Falcon 4.0 Rev. 0.0421 3 Tactical References for Falcon 4.0 TABEL OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................9 SOURCES AND RESOURCES .......................................................................................................................10 US/ALLIED MUNITIONS CHAPTER ..............................................................................................................11 FREE FALL BOMBS ....................................................................................................................................11 B-53 ............................................................................................................................................................. 11 B-61 ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 B-83 ............................................................................................................................................................. 13 BLU-1/B....................................................................................................................................................... 14 BLU-10/A.................................................................................................................................................... -

Tactical References for Falcon 4.0

Tactical Reference for Falcon 4.0 1 Tactical References for Falcon 4.0 Tactical Reference Munitions Handbook 2 Tactical Reference for Falcon 4.0 Rev. 0.0421 3 Tactical References for Falcon 4.0 TABEL OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................9 SOURCES AND RESOURCES .......................................................................................................................10 US/ALLIED MUNITIONS CHAPTER ..............................................................................................................11 FREE FALL BOMBS ....................................................................................................................................11 B-53 ............................................................................................................................................................. 11 B-61 ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 B-83 ............................................................................................................................................................. 13 BLU-1/B....................................................................................................................................................... 14 BLU-10/A.................................................................................................................................................... -

Evolved Seasparrow Missile Program

R. K. FRAZER et al. Evolved Seasparrow Missile Program R. Kelly Frazer, James M. Hanson Jr., Michael J. Leumas, Clifford L. Ratliff, Olivia M. Reinecke, and Charles L. Roe The multinational effort to develop and field the Evolved Seasparrow Missile is nearing completion. The effort, supported by a consortium of the United States and allied nations, is a significant improvement to the existing Sparrow Missile. It will provide the fleets of these nations with an anti-missile capability against existing and projected threats that possess low-altitude, higher-velocity, and maneuver capabilities that stress present systems. This article traces the Evolved Seasparrow Missile’s development from early definition efforts through engineering and manufacturing development into production transition and com- pletion of the present at-sea developmental and operational testing that will prove its capa- bilities to support consortium fleet missions. PROGRAM BACKGROUND The NATO Seasparrow Consortium grew out of a 1970s, was limited by rocket motor size in its ability unique Memorandum of Understanding first signed 34 to meet the evolving threat. At the 53rd NATO Seas- years ago by the United States and three NATO allies parrow Project Steering Committee meeting in Troms, to develop and field a state-of-the-art shipborne self- Norway, in April 1991, the NATO Seasparrow Project defense system to counter the threats to their navies Office (NSPO) presented a proposal to build an Evolved posed by anti-ship weapons.1 The sinking of the Israeli Seasparrow Missile (ESSM) (Fig. 1) for improved per- destroyer Elath in 1967 by an anti-ship missile provided formance against very fast and maneuvering low-altitude even more impetus for the NATO Seasparrow program, threats.3 This kinematic improvement would be accom- and additional countries joined the consortium, which plished by adding a rocket motor of increased diameter to now has 13 members. -

Evolution of the Cruise Missile

The Evolution of the Cruise Missile by KENNETH P. WERRELL Air University (AU) Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 1985 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Werrell, Kenneth P. The Evolution of the Cruise Missile . "September 1985 ." Includes bibliographies and index. 1 . Cruise Missiles-History . I. Air University (US) . II . Title. UG1312 .C7W47 1985 358'.174'0973 85-8131 First Printing 1985 Second Printing 1998 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the editors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents US Government Printing Office Washington DC 20402 90 t&iz c*nezieani a7lio ka(TE jzzvzJ, au jzviny, at wdl izzvE witfi tfiE ezuisz m.illiz. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK CONTENTS Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ii FOREWORD. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ix THE AUTHOR . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . .. .. .. .. ... .. xiii I INTRODUCTION . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Notes . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 II THE EARLY YEARS . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Foreign Efforts . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Navy-Sperry Flying Bomb . .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Army-Kettering Bug .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Foreign Developments . .. .. .. .. 17 The Army-Sperry Experiments . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 US -

Thinking Smarter About Defense

KNOW WHEN TO Hold ‘EM, KNOW WHEN to Fold ‘EM: A NEW TRANSFORMATION PLAN FOR THE NAvy’s SURfaCE BATTLE LINE Robert O. Work Thinking Center for Strategic and Budgetary Smarter Assessments About CSBA Defense csbaonline.org Know When to Hold ’Em, Know When to Fold ’Em: A New Transformation Plan for the Navy’s Surface Battle Line Robert O. Work Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ III I. THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD: RETRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF POST-COLD WAR PLANS FOR THE NAVY’S FUTURE SURFACE BATTLE LINE .................................................................... 1 A Rapid Fall From Grace ...................................................................................... 1 Planning Under Conditions of Scarce Resources and Uncertainty .................... 3 Impact of the Gulf War ......................................................................................... 4 A “Defining Battle” ......................................................................................... 6 The Immediate Postwar Naval Priority: Land-Attack ........................................ 12 The “Requirements School” Takes Over ........................................................... 15 When Budgets and Requirements Collide: Coming to Terms With a “300-ship Navy” ................................................................................................................. -

Marine Nuclear Power 1939 – 2018 Part 2B USA Surface Ships

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018 Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States – Submarines Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Part 4: Europe & Canada Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications. -

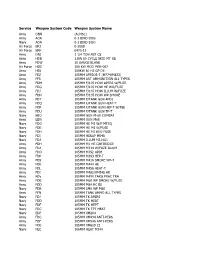

Service Weapon System Code Weapon System Name Army DBN

Service Weapon System Code Weapon System Name Army DBN (ALMSC) Army AOA 0-1 BIRD DOG Navy AOA 0-1 BIRD DOG Air Force BRJ 0-300D Air Force BRK 0470-13 Army DNI 1 1/4 TON ABT CS Army HDB 1.KW 60 CYCLE SKID MT GE Army FDW 10 GAUGE BLANK Air Force HDC 100 KW MOD MER-007 Army HDL 100KW 60 HZ GP DE Army FEZ 105MM APFSOS-T (M774/M833) Army FFS 105MM ART AMMUNITION ALL TYPES Army FDM 105MM F/105 HOW APERS W/FUZE Army FDG 105MM F/105 HOW HE WO/FUZE Army FDJ 105MM F/105 HOW ILLUM W/FUZE Army FDN 105MM F/105 HOW WP SMOKE Army FDT 105MM F/TANK GUN APDS Army FDQ 105MM F/TANK GUN HEAT-T Army FDR 105MM F/TANK GUN HEP-T W/FSE Army FDU 105MM F/TANK GUN TP-T Navy EBO 105MM GUN M-60 COMBAT Army EBN 105MM GUN M68 Navy FDG 105MM HE M1 W/F MTSQ Navy FDE 105MM HE M1 W/FUSE Navy FDH 105MM HE MI W/O FUSE Navy FDI 105MM HERAP M548 Navy FDA 105MM ILLUM M314A1 Army FDH 105MM M1 HE CARTRIDGE Army FDA 105MM M314 W/FUZE ILLUM Army FDO 105MM M392 APDS Army FDP 105MM M393 HEP-T Army FDS 105MM M416 SMOKE WP-T Army FDK 105MM M444 HE Army FDL 105MM M456 HEAT-T Army FDI 105MM M482/XM548 HE Army FDV 105MM M490 TARG PRAC TRA Army FDB 105MM M60 WP SMOKE W/FUZE Army FDD 105MM M84 HC BE Navy FDB 105MM SMK WP M60 Army FFN 105MM TANK AMMO ALL TYPES Navy FDJ 105MM TK APERS Navy FDD 105MM TK HEAT Navy FDF 105MM TK HEPT Navy FDC 105MM TK TPT HEAT Navy EDF 105MM XM204 Army FDC 105MM XM494 ANTI-PERS Army FDF 105MM XM546 ANTI-PERS Army FDE 105MM XM629 CS Navy FEC 106MM HEAT M344 Navy FED 106MM HEPT M346A1 Army FEC 106MM M344 HEAT Army FED 106MM M346 HEP-T Navy FEB 106MM XM581 BEEHIVE -

Precision-Guided Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress

Precision-Guided Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress Updated June 11, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45996 SUMMARY R45996 Precision-Guided Munitions: Background and June 11, 2021 Issues for Congress John R. Hoehn Over the years, the U.S. military has become reliant on precision-guided munitions Analyst in Military (PGMs) to execute military operations. PGMs are used in ground, air, and naval Capabilities and Programs operations. Defined by the Department of Defense (DOD) as “[a] guided weapon intended to destroy a point target and minimize collateral damage,” PGMs can include air- and ship-launched missiles, multiple launched rockets, and guided bombs. These munitions typically use radio signals from the global positioning system (GPS), laser guidance, and inertial navigation systems (INS)—using gyroscopes—to improve a weapon’s accuracy to reportedly less than 3 meters (approximately 10 feet). Precision munitions were introduced to military operations during World War II; however, they first demonstrated their utility operationally during the Vietnam War and gained prominence in Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Since the 1990s, due in part to their ability to minimize collateral damage, PGMs have become critical components in U.S. operations, particularly in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. The proliferation of anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems is likely to increase the operational utility of PGMs. In particular, peer competitors like China and Russia have developed sophisticated air defenses and anti-ship missiles that increase the risk to U.S. forces entering and operating in these regions. Using advanced guidance systems, PGMs can be launched at long ranges to attack an enemy without risking U.S.