2017 Erca Ea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural World That I Seek out in the Desert Regions of Baja California

The natural world that I seek out in the desert regions of Baja California and southern California provides me with scientific adventure, excitement towards botany, respect for nature, and overall feelings of peace and purpose. Jon P. Rebman, Ph.D. has been the Mary and Dallas Clark Endowed Chair/Curator of Botany at the San Diego Natural History Museum (SDNHM) since 1996. He has a Ph.D. in Botany (plant taxonomy), M.S. in Biology (floristics) and B.S. in Biology. Dr. Rebman is a plant taxonomist and conducts extensive floristic research in Baja California and in San Diego and Imperial Counties. He has over 15 years of experience in the floristics of San Diego and Imperial Counties and 21 years experience studying the plants of the Baja California peninsula. He leads various field classes and botanical expeditions each year and is actively naming new plant species from our region. His primary research interests have centered on the systematics of the Cactus family in Baja California, especially the genera Cylindropuntia (chollas) and Opuntia (prickly-pears). However, Dr. Rebman also does a lot of general floristic research and he co- published the most recent edition of the Checklist of the Vascular Plants of San Diego County. He has over 22 years of field experience with surveying and documenting plants including rare and endangered species. As a field botanist, he is a very active collector of scientific specimens with his personal collections numbering over 22,500. Since 1996, he has been providing plant specimen identification/verification for various biological consulting companies on contracts dealing with plant inventory projects and environmental assessments throughout southern California. -

Sauromalus Hispidus

ARTÍCULOS CIENTÍFICOS Cerdá-Ardura & Langarica-Andonegui 2018 - Sauromalus hispidus in Rasa Island- p 17-28 ON THE PRESENCE OF THE SPINY CHUCKWALLA SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) IN RASA ISLAND, MEXICO PRESENCIA DEL CHACHORÓN ESPINOSO SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) EN LA ISLA DE RASA, MÉXICO Adrián Cerdá-Ardura1* and Esther Langarica-Andonegui2 1Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic. 2Facultad de Ciencias, Uiversidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CDMX, México. *Correspondence author: [email protected] Abstract.— In 2006 and 2013 two different individuals of the Spiny Chuckwalla (Sauromalus hispidus) were found on the small, flat, volcanic and isolated Rasa Island, located in the Midriff Region of the Gulf of California, Mexico. This species had never been recorded from Rasa Island prior to 2006. A new field study in 2014 revealed the presence of a single female chuckwalla inhabiting the Tapete Verde Valley, in the south-central part of the island, occupying a territory no bigger than 10000 m2. A scat analysis shows that the only food consumed by the animal is the Alkali Weed (Cressa truxilliensis) that forms patches of carpets in its habitat. The individual is in precarious condition, as it seems to starve on a seasonal basis, especially during El Niño cycles; also, it is missing fingers and toes, which appear to be intentional markings by amputation. We conclude that the two individuals were introduced to the island intentionally by humans. Keywords.— Chuckwalla, Gulf of California, Rasa Island. Resumen.— En 2006 y 2013 se encontraron dos individuos diferentes del cachorón de roca o chuckwalla espinoso (Sauromalus hispidus) en la pequeña, plana, volcánica y aislada isla Rasa, localizada en la Región de las Grandes Islas, en el Golfo de California, México. -

Taxonomy and Distribution of Opuntia and Related Plants

Taxonomy and Distribution of Opuntia and Related Genera Raul Puente Desert Botanical Garden Donald Pinkava Arizona State University Subfamily Opuntioideae Ca. 350 spp. 13-18 genera Very wide distribution (Canada to Patagonia) Morphological consistency Glochids Bony arils Generic Boundaries Britton and Rose, 1919 Anderson, 2001 Hunt, 2006 -- Seven genera -- 15 genera --18 genera Austrocylindropuntia Austrocylindropuntia Grusonia Brasiliopuntia Brasiliopuntia Maihuenia Consolea Consolea Nopalea Cumulopuntia Cumulopuntia Opuntia Cylindropuntia Cylindropuntia Pereskiopsis Grusonia Grusonia Pterocactus Maihueniopsis Corynopuntia Tacinga Miqueliopuntia Micropuntia Opuntia Maihueniopsis Nopalea Miqueliopuntia Pereskiopsis Opuntia Pterocactus Nopalea Quiabentia Pereskiopsis Tacinga Pterocactus Tephrocactus Quiabentia Tunilla Tacinga Tephrocactus Tunilla Classification: Family: Cactaceae Subfamily: Maihuenioideae Pereskioideae Cactoideae Opuntioideae Wallace, 2002 Opuntia Griffith, P. 2002 Nopalea nrITS Consolea Tacinga Brasiliopuntia Tunilla Miqueliopuntia Cylindropuntia Grusonia Opuntioideae Grusonia pulchella Pereskiopsis Austrocylindropuntia Quiabentia 95 Cumulopuntia Tephrocactus Pterocactus Maihueniopsis Cactoideae Maihuenioideae Pereskia aculeata Pereskiodeae Pereskia grandiflora Talinum Portulacaceae Origin and Dispersal Andean Region (Wallace and Dickie, 2002) Cylindropuntia Cylindropuntia tesajo Cylindropuntia thurberi (Engelmann) F. M. Knuth Cylindropuntia cholla (Weber) F. M. Knuth Potential overlapping areas between the Opuntia -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Disturbance, Restoration, and Soil Carbon Dynamics in Desert and Tropical Ecosystems a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Disturbance, Restoration, and Soil Carbon Dynamics in Desert and Tropical Ecosystems A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Plant Biology by Amanda Cantu Swanson September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Edith B. Allen, Chairperson Dr. G. Darrel Jenerette Dr. James O. Sickman Copyright by Amanda Cantu Swanson 2017 The Dissertation of Amanda Cantu Swanson is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my principal advisor, Dr. Edith B. Allen, for seeing my potential when I was a student volunteer and for encouraging me to be a restoration and plant ecologist. She has been a wonderful mentor, resource, and colleague, and her guidance has enabled me to succeed in graduate school. Working in her lab has been an invaluable experience that will serve me throughout my career. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Michael F. Allen, who informally co-advised me during my Ph.D. He has also been an incredible teacher and supporter, whose wisdom and creativity have further inspired me to ask novel scientific questions and pursue a career in research. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee members Dr. G. Darrel Jenerette and Dr. James Sickman for their unwavering support and guidance. Several other faculty and collaborators have generously given their time, resources, and support to help me with my dissertation: Dr. Emma Aronson, Dr. Cameron Barrows, Jon Botthoff, Dr. Diego Dierick, Dr. Mark De Guzman, Mark Fisher, Dr. Rebecca Hernandez, Dr. Liyin Liang, Dr. Allen Muth, Dr. -

Botanical92-1 Digital

Botanical Sciences 92 (1): 89-101, 2014 TAXONOMY AND FLORISTICS FLORISTIC DIVERSITY AND DYNAMICS OF ISLA RASA, GULF OF CALIFORNIA – A GLOBALLY IMPORTANT SEABIRD ISLAND ENRIQUETA VELARDE1, BENJAMIN T. WILDER2,6, RICHARD S. FELGER3,4 AND EXEQUIEL EZCURRA2,5 1Instituto de Ciencias Marinas y Pesquerías, Universidad Veracruzana, Boca del Río, Veracruz, Mexico 2Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, California, USA 3University of Arizona Herbarium, Tucson, Arizona, USA 4Sky Island Alliance, Tucson, Arizona, USA 5University of California, Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS), Riverside, California, USA 6Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: Isla Rasa, a small (0.68 km2) but globally important seabird island in the Gulf of California, has a fl ora of only 14 vas- cular plant species found in three vegetation zones. Signifi cant physical alteration of the island’s surface and the introduction of non-native rodents, eradicated in 1995, add restoration ecology to the remarkable biology of the island. Over a century of botanical collections and observations record a consistently depauperate fl ora, best understood in the context of extreme aridity, isolation, and elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorus from bird guano. The shaping factor of guano on the dearth of fl oristic diversity illustrates close connection between marine and terrestrial ecosystems in the Gulf of California. El Niño events that trigger collap- ses in marine productivity and crashes in seabird reproduction bring above-average winter rainfall pulses and rapid plant growth. Two new island records are reported (Rhizophora mangle and Viscainoa geniculata). Matched photographs show signifi cant in- crease in the cholla cactus (Cylindropuntia fulgida) since 1971. -

Exceptional Successes with Biological Control of Invasive Cacti in the North-Western Grasslands

Exceptional successes with biological control of invasive cacti in the north-western grasslands Helmuth Zimmermann & Hildegard Klein Helmuth Zimmermann & Associates (Central) Plant Protection Research Institute, ARC, Pretoria Contents • Introduction to invasive alien plants in the north-western grasslands • The invasive cacti • History of control • Recent biological control successes Cochineal biotypes and the new association effect Before-and-after results of using new biotypes of Dactylopius species • Dealing with new emerging cactus invaders • Conclusion Invasive alien plants in the north-western grasslands Western North West Province Northern Cape North-east Western Cape North-west Free State North-western grasslands Transformer invasive alien plants in the north-western grasslands • Cactus species •Prosopis species and hybrids •Tamarix species The main invaders Prosopis hybrids Tamarix spp The main invaders: the Cacti The cactus species Important species Opuntia Chollas Others Opuntia ficus-indica Cylindropuntia fulgida var. fulgida Tephrocactus auriculata Opuntia stricta Cylindropuntia fulgida var. mamillata Trichocereus schickendantzii Opuntia humifusa Cylindropuntia imbricata Harrisia martinii Opuntia aurantiaca Cylindropuntia pallida Opuntia engelmannii Cylindropuntia leptocaulis Emerging species Cylindropuntia spinosior Opuntia elata Trichocereus pachanoi Harrisia tortuosa The main invaders: cactus species Cylindropuntia pallida Cylindropuntia fulgida var. fulgida The main invaders: cactus species Cylindropuntia fulgida var. mamillata Cylindropuntia imbricata The main invaders: cactus species Opuntia engelmannii Opuntia stricta The main invaders: cactus species Opuntia humifusa Opuntia aurantiaca Chemical control: effective but VERY costly and a serious hazard to the environment. Two Biological Control Agents 1. Cactoblastis cactorum. This biological control agent is important in the biocontrol of Opuntia species. It is effective against small plants. It played a major role in the biological control of prickly pear: Opuntia ficus indica. -

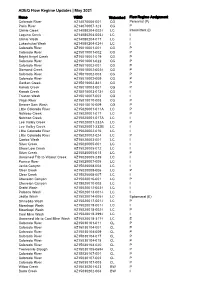

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021 Name WBID Watershed Flow Regime Assignment Colorado River AZ14070006-001 CG Perennial (P) Paria River AZ14070007-123 CG P Chinle Creek AZ14080204-002-I LC Intermittent (I) Laguna Creek AZ14080204-003-I LC I Chinle Wash AZ14080204-017 LC I Lukachukai Wash AZ14080204-024-I LC I Colorado River AZ15010001-001 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-002 CG P Bright Angel Creek AZ15010001-019 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-022 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-001 CG P Diamond Creek AZ15010002-002-I CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-003 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-009 CG P Garden Creek AZ15010002-841 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-001 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-013-I CG I Truxton Wash AZ15010007-002 CG I Virgin River AZ15010010-003 CG P Beaver Dam Wash AZ15010010-009 CG P Little Colorado River AZ15020001-011A LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017 LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017A LC I Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232A LC P Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232B LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-016 LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-024 LC P Carrizo Wash AZ15020003-001 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-001 LC I Show Low Creek AZ15020005-012 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-013 LC P Unnamed Trib to Walnut Creek AZ15020005-239 LC I Puerco River AZ15020007-005 LC I Jacks Canyon AZ15020008-004 LC I Clear Creek AZ15020008-006 LC P Clear Creek AZ15020008-007 LC I Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-001 LC P Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-003 LC I Oraibi Wash AZ15020012-003-I LC I Polacca Wash AZ15020013-001-I LC I Jadito Wash AZ15020014-005-I LC Ephemeral -

Snake Cactus (Cylindropuntia Spinosior)

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry Biosecurity Queensland Restricted invasive plant The rabbit and its control WildOryctolagusSnake dog cuniculuscactus control CanisCylindropuntia familiaris spinosior Snake cactus can form dense infestations that will In Queensland it is illegal to sell snake cactus on compete with native vegetation, limiting the growth of Gumtree, Ebay, Facebook, at markets, nurseries or any small shrubs and groundcover species. Snake cactus can marketplace. also reduce pastures. Snake cactus can harbour invasive animals, such as foxes and rabbits and, due to their spiny nature, can limit access for stock mustering and recreational activities. The spines or barbs can cause injury to stock and native animals, reducing or preventing grazing activities and productivity. Legal requirements Asexual reproduction (cloning) of snake cactus occurs when pads (joints, segments) or fruits located on the Snake cactus is a restricted category 3 invasive plant ground take root and produce shoots. Flowering usually under the Biosecurity Act 2014. It must not be given away, occurs in spring and early summer. sold, or released into the environment. The Act requires everyone to take all reasonable and practical steps to minimise the risks associated with invasive plants under Methods of spread their control. This is called a general biosecurity obligation Animals and floods move broken stems long distances. (GBO). This fact sheet gives examples of how you can meet These stems can survive long periods of drought before your GBO. weather conditions allow them to set roots. It can also spread by machinery, vehicles and footware and from At a local level, each local government must have a ornamental plantings. -

Cylindropuntia & Cylindropuntia Invasive Cacti Are a Serious Threat to Biodiversity and Agricultural Systems Within Australian Rangeland Regions

w Invasive cacti a prickly problem Austrocylindropuntia & Cylindropuntia Invasive cacti are a serious threat to biodiversity and agricultural systems within Australian rangeland regions. The key features listed may assist you to identify these prickly invaders. Austrocylindropuntia cylindrica Austrocylindropuntia subulata Cylindropuntia fulgida var. mamillata Cane cactus Eve’s-pin cactus Coral cactus, boxing glove cactus K C Erect, branching shrub Branching shrub to 3m tall. Erect shrub up to 0.4-0.8m CHINNO 0.3-1.5m tall. Often forms Forms patches to 8m wide. tall. Deciduous leaves. Rarely B BO patches several metres wide. Leaves can persist. flowers/fruits. Green-grey green. Dark bluish-green, shiny. Mid green. Slender, to Stem Segments Stem Segments Stem Segments Stem Segments Stem Segments Stem Segments Often distorted, with a K K C Rounded, 15-50cm long, 50cm long, 4-5cm diameter. C Stem Segments Stem Segments corrugated (tuberculate) Stem Segments Stem Segments 3-4cm diameter. Deciduous Leaves to 12cm long. Flowers Flowers Stem Segments Stem Segments surface, 10-22cm long, CHINNO StemFlowers Segments StemFlowers Segments Flowers Flowers CHINNO B leaves to 1cm long. B 2-4.5cm diameter. Often BO Pink.Flowers Flowers BO Stem Segments Stem Segments StemFlowers Segments Stem SegmentsFlowers numerous, easily detached Flowers Flowers StemFruits Segments StemFruits Segments Red,FlowersFruits cup shaped. FlowersFruits Fruits Fruits small segments. Oblong,Fruits egg or club shapedFruits Flowers Flowers Flowers Flowers Stem Segments Stem Segments Fruits Fruits DeepSpines red. Spines EggFruits to urn shaped, to Fruits to 10cm long. Green. StemFlowers Segments Stem SegmentsFlowers FruitsSpines FruitsSpines Spines Spines 4.5cm long. Deep (CanFruits produce chains).Fruits Flowers Flowers Spines Spines InverseFruits cone or oval Fruits Spines Spines Flowers Flowers green-yellowSpines green. -

Current Knowledge and Conservation of Cylindropuntia Multigeniculata (Cactaceae), the Blue Diamond Cholla

Current Knowledge and Conservation of Cylindropuntia multigeniculata (Cactaceae), the Blue Diamond cholla Marc A. Baker Southwest Botanical Research 1217 Granite Lane Chino Valley, AZ 86323 (928) 636-0252 15 June 2005 Status report prepared for U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard, suite 234, Reno NV 89502. (775) 861 6300 with funds provided through Project Agreement in cooperation with Prescott College, Prescott, Arizona SUMMARY : The typical form of the Blue Diamond cholla, Cylindropuntia multigeniculata , is now known to occur from north of Las Vegas, near Gass Peak, in the Las Vegas Range, southwest into the La Madre Mountain area, south to Blue Diamond, and then southeast into the McCullough Range. The knowledge of new localities is largely owing to efforts of Gina Glenne of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and Pat Putnam and Jed Botsford of the Bureau of Land Management. Prior to these discoveries, the Blue Diamond cholla was known to occur only at its type locality in the Blue Diamond Hills, just west of Las Vegas. Current surveys indicate that populations of C. multigeniculata conservatively occupy at least 25km² with densities averaging 23 individuals per hectare, thus the conservative estimate of number of individuals is 56,500. This estimate does not include at least one population in the Sheep Range that appear to be comprised of individuals morphologically intermediate between C. multigeniculata and C. whipplei var. whipplei . Populations of C. multigeniculata with consistently spiny fruits occur from Bonelli Peak, Gold Butte area of eastern Clark County, Nevada, south into the White Hills and Black Mountains of Mojave County, Arizona. -

Morphological Seeds Descriptors for Characterize and Differentiate Genotypes of Opuntia (Cactaceae, Opuntioideae)

Annual Research & Review in Biology 4(24): 3791-3809, 2014 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Morphological Seeds Descriptors for Characterize and Differentiate Genotypes of Opuntia (Cactaceae, Opuntioideae) Samir Samah1 and Ernestina Valadez-Moctezuma1* 1Laboratorio de Biología Molecular, Departamento de Fitotecnia, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Carretera México- Texcoco km 38.5 Chapingo, Edo. México, 56230, México. Autores’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Author EVM wrote the protocol and supervised the work in all its aspects. Author SS collected the samples, worked in the practical part and written the draft of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Received 24th May 2014 th Original Research Article Accepted 25 June 2014 Published 8th July 2014 ABSTRACT Aims: In this paper, a morphometric study was carried out to analyze the variation of seeds of Opuntia accessions using several statistical approaches. The main objective was to select morphological seeds variables for characterization and differentiation of Opuntia genotypes. Place and Duration of Study: The research was conducted in Crops Science Department of the Chapingo Autonomous University, Mexico. The sample collection was down in 2012. Seed data was obtained during 2013. Methodology: A total of 110Opuntia accessions (some classified and other ones with no specific taxonomic assignation), one accession of Cylindropuntia sp. (Cactaceae, Opuntioideae) and two other out groups (Cactaceae, Pachycereae) were used. Nineteen internal and external seeds variables were obtained using image analysis. Basic statistical analysis, analysis of variance, principal component analysis, cluster and discriminant analysis were performed. Results: Highly significant differences among accessions for all seed characters were showed. -

Codes for the Identification of Hydrologic Units in the United States and the Caribbean Outlying Areas Date of Approval: July 1981 Maintenance Organization: U.S

A U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DATA STANDARD This report describes one of a series of data standards adopted and im¬ plemented by the U.S. Geological Survey for the standardization of data elements and representations used in automated Earth-science systems. Earth sciences are those scientific disciplines especially required to carry out the mission of the Geological Survey and are concerned with the material and morphology of the Earth and physical forces relating to the Earth. These disciplines include geology, topography, geography, and hydrology. The Geological Survey has assumed the leadership in developing and main¬ taining Earth-science data element and representation standards for use in the Federal establishment under the terms of a Memorandum of Understand¬ ing signed in February 1980 by the National Bureau of Standards of the Department of Commerce and the Geological Survey, a Bureau of the Depart¬ ment of the Interior. As such, in addition to developing and maintaining standards, the Geological Survey reviews and processes all requests referred by the National Bureau of Standards for exceptions, deferments, and revi¬ sion of standards applicable to Federal Earth-science information systems; assists the National Bureau of Standards in assessing the need, impact, benefits, and problems related to the implementation of standards being con¬ sidered for development, or developed, for use in the Earth sciences; and works with other agencies in developing new data standards in the Earth sciences. The standard described in this report has been specifically approved for use within the U.S. Geological Survey. If the standard has been approved for use throughout the Federal establishment, it is also published by the National Bureau of Standards as a Federal Information Processing Standard.