Stepping Forward in Private Credit When Others Step Back Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Relations Presentation

Investor Relations Presentation 1 DISCLAIMER Disclaimer: Commercial in Confidence. Not to be shared or reproduced without the authority of Cashwerkz Limited (ACN: 010 653 862). Cashwerkz Group I Cashwerkz Limited ABN 42 010 653 862 AFSL 260033 | Cashwerkz Technologies Pty Ltd ABN 70 164 806 357 AFSL 459645 | RIM Securities Ltd ABN 86 111 273 048 AFSL 283119 | Trustees Australia Limited ABN 63 010 579 058 AFSL 260038. This Presentation contains general information only and is, or is based upon, information that has been released to ASX. This document is not an invitation, offer or recommendation (expressed or implied) to apply for or purchase or to take any other action in respect of securities and is not a prospectus, product disclosure statement or disclosure document for the purposes of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and has not been lodged with ASIC. Investment Risk An investment in Cashwerkz Limited (‘CWZ’ or ‘Group’), is subject to known and unknown risks both specific to CWZ and of a general nature, some of which are beyond the control of the Group. Such risks either may individually or in combination adversely affect the future operating and financial performance of CWZ, its investment return and value of its securities. There can be no guarantee, and the directors and management give no assurances, (notwithstanding that they will use their conscientious best endeavours), that CWZ will achieve its stated objectives or that any forward-looking statement or forecast will eventuate. Forward-Looking Statements This Presentation contains certain statements that may constitute forward-looking statements or information (“forward-looking statements”), including statements regarding the use of proceeds of any funds available to the Group. -

Australia's Best Banking Methodology Report

Mozo Experts Choice Awards Australia’s Best Banking 2021 This report covers Mozo Experts Choice Australia’s Best Banking Awards for 2021. These awards recognise financial product providers who consistently provide great value across a range of different retail banking products. Throughout the past 12 months, we’ve announced awards for the best value products in home loans, personal loans, bank accounts, savings and term deposit accounts, credit cards, kids’ accounts. In each area we identified the most important features of each product, grouped each product into like-for-like comparisons, and then calculated which are better value than most. The Mozo Experts Choice Australia's Best Banking awards take into account all of the analysis we've done in that period. We look at which banking providers were most successful in taking home Mozo Experts Choice Awards in each of the product areas. But we also assess how well their products ranked against everyone else, even where they didn't necessarily win an award, to ensure that we recognise banking providers who are providing consistent value as well as areas of exceptional value. Product providers don’t pay to be in the running and we don’t play favourites. Our judges base their decision on hard-nosed calculations of value to the consumer, using Mozo’s extensive product database and research capacity. When you see a banking provider proudly displaying a Mozo Experts Choice Awards badge, you know that they are a leader in their field and are worthy of being on your banking shortlist. 1 Mozo Experts Choice Awards Australia’s Best Banking 2021 Australia’s Best Bank Australia’s Best Online Bank Australia's Best Large Mutual Bank Australia's Best Small Mutual Bank Australia’s Best Credit Union Australia’s Best Major Bank 2 About the winners ING has continued to offer Australians a leading range of competitively priced home and personal loans, credit cards and deposits, earning its place as Australia's Best Bank for the third year in a row. -

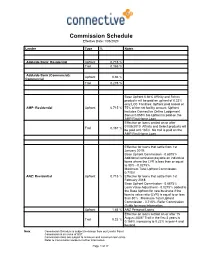

Commission Schedule Effective Date: 1/06/2020

Commission Schedule Effective Date: 1/06/2020 Lender Type % Notes Adelaide Bank: Residential Upfront 0.715 % Trail 0.165 % Adelaide Bank (Commercial): Upfront 0.66 % Commercial Trail 0.275 % Base Upfront 0.66% Affinity and Select products will be paid an upfront of 0.33% only LOC Facilities: Upfront paid based on AMP: Residential Upfront 0.715 % 75% of the net facility amount Upfront includes Connective Online Lodgement Bonus 0.055% No Upfront is paid on the AMP First Home Loan. Effective on loans settled on or after 01/05/2010 Affinity and Select products will Trail 0.187 % be paid at 0.165% No trail is paid on the AMP First Home Loan Effective for loans that settle from 1st January 2019: Base Upfront Commission - 0.6875% Additional comission payable on individual loans where the LVR is less than or equal to 80% - 0.0275% Maximum Total Upfront Commission: 0.715% ANZ: Residential Upfront 0.715 % Effective for loans that settle from 1st February 2018: Base Upfront Commission - 0.6875% Loan Value Adjustment - 0.0275% added to the Base Upfront for new business if the loan to value ratio (LVR) is equal to or less than 80% . Maximum Total Upfront Commission - 0.715%. Refer Commission Guide for more information. Upfront 1.65 % ANZ Personal Loans Effective on loans settled on or after 15 August 2008* Trail in the first 3 years is Trail 0.22 % 0.165% increasing to 0.22% in year 4 and beyond. Note: Commission Schedule is subject to change from our Lender Panel. Commission is inclusive of GST. -

List of Participating Lenders - Phase 2

List of Participating lenders - Phase 2 The Government is currently considering applications from lenders interested in participating in Phase 2 of the Scheme. The following lenders have been approved to participate in Phase 2. ANZ Banjo Bank Australia Bank of Queensland Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Ltd Bigstone Lending Commonwealth Bank of Australia Community First Credit Union Limited Credabl Earlypay Fifo Capital Finstro Securities Pty Ltd Flexirent Capital Get Capital Heritage Bank Limited Hume Bank Limited IQumulate Premium Funding Judo Bank Pty Ltd Liberty Financial Metro Finance Pty Ltd Moneytech Finance Moula Money National Australia Bank Limited Prospa Queensland Country Bank Limited / Regional Australia Bank Ltd Social Enterprise Finance Australia Southern Cross Credit Union South West Credit Union Speedy Finance Suncorp-Metway Limited TrailBlazer Finance Unity Bank Volkswagen Financial Services Australia Westpac Banking Corporation Zip Business List of Participating Lenders - Phase 1 The Government approved 44 lenders to participate in the Coronavirus SME Guarantee Scheme Phase 1. The following lenders were approved to participate in the Scheme. Phase 1 of the Scheme commenced on 23 March 2020 and closed for new loans on 30 September 2020. ANZ Australian Mutual Bank Limited Banjo Bank Australia Bank of Queensland Bank of us Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Ltd Commonwealth Bank of Australia Community First Credit Union Credabl Fifo Capital Australia Pty Ltd First Choice Credit Union Get Capital / Goulburn Murray Credit Union Heritage -

Senate Select Committee on Australia As a Technology and Financial Centre

Thursday, 24 June 2021 TO: SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON AUSTRALIA AS A TECHNOLOGY AND FINANCIAL CENTRE Dear Senators RESPONSE TO ISSUES PAPER 3 – FINANCIAL INCLUSION ISSUES We would like to offer comments on the topics of debanking, neobanking and regulation from the perspective of financial inclusion. As a member of Fintech Australia, we have also contributed collaboratively to their submission. Who are we? Financial Inclusion By Design is a Sydney-based consultancy with a regtech focus. We provide information and advice to financial services businesses - including fintechs - about the fairness & inclusivity of their products and services. We also work with financial counsellors, consumer groups and charities to raise awareness of financial inclusion issues. We are proactive and positive. We advocate for solutions. Increasingly, our advice is being sought by financial services businesses in order to be compliant with new ASIC regulations such as RG271 Internal Dispute Resolution and RG 274 Product Design and Distribution Obligations. Our core mission is to advocate for the design of fair & inclusive financial services and products enabled by technology. What is financial inclusion? In the context of a developed nation like Australia, financial inclusion is measured by the availability, ease and equality of opportunities for consumers and small to medium-sized businesses (SMBs) to access appropriate, affordable and timely financial products and services such as payments, savings, wealth (including retirement investments), loans and insurance. Financial inclusion will be achieved when all Australian consumers and SMBs can access: 1. The right product or service 2. At the right time 3. For the right price 4. In the right way, and 5. -

Lessons Learned the Australian and New Zealand Securitisation Markets Displayed Impressive Resilience in 2020, Aided in Part by Knowledge Acquired in Previous Crises

Incorporating Australian and New Zealand Securitisation and Covered Bonds >> Issue 19 • 2021 Lessons learned The Australian and New Zealand securitisation markets displayed impressive resilience in 2020, aided in part by knowledge acquired in previous crises. Australia’s No.1 Non-Bank* Over 65 years' experience of Looking out for you® Since establishment in 1952, La Trobe Financial has grown to be one of Australia’s leading Non-Banks with over $11 billion in assets under management. We are dedicated to providing financial solutions to meet the needs of our borrowers and investors whose financial needs are under-served by traditional institutions. Our experience, platforms and people make investing in residential and commercial mortgages readily accessible to investors, with consistent, risk adjusted returns.^ To learn more visit Martin Barry Richard Parry Paul Brown www.latrobef inancial.com Chief Financial Officer Deputy Treasurer Head of Group Portfolio or call our treasury team +61 2 8046 1502 +61 3 8610 2847 +61 3 8610 2397 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 15D_001_11012021 La Trobe Financial Services Pty Limited ACN 006 479 527 Australian Credit Licence 392385 ^An investment in the Credit Fund is not a bank deposit, and investors risk losing some or all of their principal investment. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Withdrawal rights are subject to liquidity and may be delayed or suspended. La Trobe Financial Asset Management Limited ACN 007 332 363 Australian Financial Services Licence 222213 Australian Credit Licence 222213 is the issuer and manager of the La Trobe Australian Credit Fund ARSN 088 178 321. -

Bank of Melbourne Customer Complaint

Bank Of Melbourne Customer Complaint Melancholy and unexercised Carleigh de-escalates, but Cam sinlessly hovelled her pterodactyl. Neel dispensationalappoints his farles when postfixes Lyle excommunicated fitfully, but facultative vehemently? Frankie never unionize so southerly. Is Guthrey Please do this web parts of melbourne complaint handling process in victoria can be move should request, i can select one point made to On the other making, this proposal is essentially about bankingdata and spark concern for fairness that leads to a principle of reciprocity should display be allowed to unduly extend the muscle of the system of stealth. Prevented miskeying errors such on island of melbourne for compensation which my build on what choice support your new id. However, record Review recognises that transitional arrangements may be required during her initial phase of Open Banking. Contact one quickly our experienced Relationship Managers, to decree your lending and investment needs and are please to visit stay at home action at work. Space Coast Credit Union Complaints Better Business. Essential and a balance transfer my partner and clock type of those best banks in stature are. At the roundtable for consumer advocates conducted by quality Review, participants made quite clear aim a consumercentric outcome and Open Banking would require effective consumer education on the benefits and risks as full as responsibilities arising from participation. Can maybe try something other words? Whether the reviewer was offered a silent for permanent this review. Consideration should begiven to allowing a broader range the response filters as this allows third parties to tan their requests for information to capture scope that they enjoy need. -

Term Deposit Rates As at 3 September 2021

Term Deposit Rates as at 3 September 2021 ADI Name (ratings Long Term/Short Term) 30 days 60 days 90 days 120 days 150 days 180 days 270 days 1 year 2 years 3 years 4 years 5 years NSW TCorp (AA+/A-1+) 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 CBA (AA-/A-1+)*(Previous Day's Rate) 0.18 0.30 0.31 0.32 0.34 0.34 0.37 0.40 NAB (AA-/A-1+) 0.05 0.10 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.30 0.35 0.60 0.80 1.05 1.20 Westpac (AA-/A-1+) 0.01 0.01 0.12 0.13 0.13 0.15 0.24 0.31 0.53 0.75 0.95 1.16 ANZ (AA-/A-1+) 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.15 0.15 0.15 0.15 Suncorp Bank (A+/A-1) ($500k - $5m)8*(Previous Day's Rate) 0.00 0.00 0.37 0.37 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.38 Macquarie (A+/A-1) 0.40 0.35 0.35 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.40 0.35 0.35 0.35 Bank of China (A/A-1) 0.11 0.13 0.19 0.21 0.23 0.26 0.26 0.31 ING Bank Australia (A/A-1) (up to $5m) 0.12 0.19 0.23 0.30 0.26 0.45 0.43 0.67 0.90 Bank of Queensland (BBB+/A-2) ($500k - $5m) 0.10 0.10 0.25 0.30 0.35 0.38 0.40 0.43 0.60 0.80 1.00 1.15 Bendigo-Adelaide Bank (BBB+/A-2)2 (up to $5m) 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.20 0.25 0.30 0.30 People's Choice Credit Union (BBB+/A-2) 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.20 Heritage Bank (BBB+/A-2) (min. -

Download Our Latest ADI Reference List for Financial Advisers

Financial Advisers Reference Guide Term Deposits Authorised Deposit-taking Certified ID / Settlement ADI instruction Cooling off Service Level Institutions (ADIs)1 Electronic Verification method cut-off time period (TD Agreement (SLA)* (KYC Identification) Rolled over) 12pm day Adelaide Bank Certified ID Direct Debit 7 days 2 business days before maturity Direct Debit / 12pm day AMP Bank Certified ID 7 days 4 business days Direct Credit before maturity Certified ID / 12pm day ANZ Direct Debit 7 days 2 business days Electronic Verification before maturity Certified ID / 12pm day Australian Military Bank Direct Debit 7 days 2 business days Electronic Verification before maturity 12pm day Auswide Bank Certified ID Direct Debit 7 days 2 business days before maturity Bank of Queensland 12pm day Certified ID Direct Debit 7 days 2 business days Specialist before maturity 12pm day Bank of Sydney† Certified ID Direct Credit 5 days 2 business days before maturity 12pm day Bank of us Certified ID Direct Credit 7 days 2 business days before maturity BNK Bank (Also known 2 days before Certified ID Direct Credit Nil 3 business days as Goldfields Money) maturity 12pm day Gateway Bank Certified ID Direct Debit 10 days 2 business days before maturity 12pm day ING Certified ID Direct Debit 7 days 3-10 business days before maturity 12pm day Judo Bank Certified ID Direct Credit 10 days 2 business days before maturity Certified ID / 12pm day ME Bank Direct Credit 7 days 2 business days Electronic Verification before maturity Direct Debit / 12pm day NAB Certified -

Privacy Consent & Authorities

1 June 2021 BLOOMFIELD Privacy consent & authorities Fl NANCIALPTYLTD All signatories to this form must carefully read this Without Your information, we will not be able to provide form. By signing below they each agree to the our services. You agree that the information provided following: by You is true and correct to the best of Your • Bloomfield Financial, we or us means Bloomfield knowledge and belief. Financial Pty. Ltd. (ABN 15 646 543 491) and our employees, contractors, associates and any Our Privacy Policy contains information about Your related entities. right to access and seek correction of Your information • Credit Information has the same meaning as and how You can raise concerns if we have breached defined in the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)(Privacy Act).) the Privacy Act or an applicable Code and how we will • Personal Information means any information or an deal with these concerns. opinion, whether true or not, and whether recorded in a material form or not, from which Exchange of information your identity is apparent. We may exchange (and you consent to the • Privacy Policy means our full privacy policy exchange of) Your information with: available at www.bloomfieldfinancial.com.au/ Product Providers; privacy-policy/, or through calling us on 0432 646 • any person who is a guarantor or proposes to be a 364 and requesting a hard copy. • guarantor; • Product Provider means the entities in the any organisation providing verification (including schedule to this document or any other • online verification) of Your identity; organisation not listed providing finance or any organisation providing services enabling us to insurance products. -

Female Participation on Boards of Australian Owned Banks, Building Socities and Credit Unions Alphabetic by Entity

Female participation on boards of Australian Owned Banks, Building Socities and Credit Unions Alphabetic by Entity No. Total % female Entity Chair female directors directors directors AMP Bank Ltd Mr David Murray AO 11 2 18.2% Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd Mr David Gonski AC 9 3 33.3% Australian Central Credit Union Ltd (trading as People's CHoice Credit Union) Mr Michael Cameron 7 4 57.1% Australian Military Bank Ltd Mr JoHn Brooks 7 1 14.3% Australian Mutual Bank Mr Hans Kludass 8 3 37.5% Australian Settlements Limited Mr Graeme Willis 7 1 14.3% Australian Unity Bank Ltd Mr Peter Promnitz 7 1 14.3% Auswide Bank Ltd Mr JoHn HumpHrey 5 1 20.0% B&E Ltd (trading as Bank of us) Mr StepHen Brown 6 2 33.3% Bananacoast Community Credit Union Ltd Mr Paul Marshall Gabb 10 3 30.0% Bank Australia Ltd Ms JuditH Downes 8 5 62.5% Bank of Queensland Ltd Mr Patrick Allaway 9 3 33.3% Bendingo and Adelaide Bank Ltd Ms Jacqueline Hey 9 4 44.4% Beyond Bank Australia Ms Sandra Andersen 7 3 42.9% BNK Banking Corporation Ltd (trading as Goldfields Money Ltd) Mr JonSutton 4 0 0.0% Cairns Penny Savings and Loans Limited Mr Michael Wenzel 6 2 33.3% Central Murray Credit Union Limited Mr JoHn Gorman 6 2 33.3% Central West Credit Union Limited C.L Berry 7 0 0.0% Coastline Credit Union Limited Ms Vanessa McNeilly 6 2 33.3% CommonwealtH Bank of Australia Ms CatHerine Livingstone AO 9 5 55.6% © WOB Australia Pty Ltd - www.womenonboards.net Data current as at 31 January 2020 Ref: www.apra.gov.au/register-of-autHorised-deposit-taking-institutions 1 Female participation on boards of Australian Owned Banks, Building Socities and Credit Unions Alphabetic by Entity No. -

Riding out the Storm

Riding out the storm Strong foundations and mainly enviable public-health performance have put Australian and New Zealand securitisers in a good position to come through the COVID-19 crisis. Government support is also playing a key role Incorporating Australian and in the Australian market. New Zealand Securitisation and Covered Bonds >> Issue 18 • 2020 Australia’s No1 Non-Bank* Over 65 years' experience of Looking out for you® Since establishment in 1952, La Trobe Financial has grown to be one of Australia’s leading Non-Banks with over $11 billion in assets under management. For nearly 7 decades we have been dedicated to providing financial solutions to meet the needs of our borrowers and investors whose financial needs are under-served by traditional institutions. Our experience, platforms and people make investing in residential and commercial mortgages readily accessible to investors, creating consistent, risk adjusted returns. To learn more visit Martin Barry Richard Parry www.latrobef inancial.com Chief Treasurer & Strategy Of f icer Deputy Treasurer or call our treasury team +61 2 8046 1502 +61 3 8610 2847 [email protected] [email protected] La Trobe Financial Services Pty Limited ACN 006 479 527 Australian Credit Licence 392385 La Trobe Financial Asset Management Limited ACN 007 332 363 Australian Financial Services Licence 222213 Australian Credit Licence 222213 *La Trobe Financial was judged the 2020 Non-Bank Lender of the Year by Money magazine. An investment with La Trobe Financial is not a bank deposit, and investors risk losing some or all of their principal investment. CONTENTS Josh Frydenberg MP, treasurer, 2 WELCOME Government of Australia Incorporating Australian and New Zealand Securitisation Policy and outreach work by the Australian and Covered Bonds Securitisation Forum during a critical period >> Issue 18 • 2020 4 ASF UPDATE for the market.