Non-Native Pond Sliders Cause Long-Term Decline of Native Sonora Mud Turtles: a 33-Year Before-After Study in an Undisturbed Natural Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endangered Species Bulletin, May/June 2003 - Vol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Endangered Species Bulletins and Technical Reports (USFWS) US Fish & Wildlife Service May 2003 Endangered Species Bulletin, May/June 2003 - Vol. XXVIII No. 3 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/endangeredspeciesbull Part of the Biodiversity Commons "Endangered Species Bulletin, May/June 2003 - Vol. XXVIII No. 3" (2003). Endangered Species Bulletins and Technical Reports (USFWS). 10. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/endangeredspeciesbull/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Fish & Wildlife Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Endangered Species Bulletins and Technical Reports (USFWS) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Human beings are the only living things that care about lines on a map. Wild animals and plants know no borders, and they are unaware of the social and economic forces that deter- mine their future. Because May/June 2003 Vol. XXVIII No. 3 many of these creatures are migratory or distributed across the artificial bound- aries that we humans have drawn, they cannot be con- served without the coopera- tion of government, private sector, and scientific partners in each of the affected coun- tries. Such wide-scale partici- pation is essential for apply- ing an ecosystem approach to wildlife conservation. This edition of the Bulletin features some examples of cooperative activities for the survival and recovery of rare plants and animals in Mexico and bordering areas of the United States. U.S.U.S. -

History of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/historyofquitobaOOnati ; 2 ? . 2 H $z X Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit ARIZONA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 2 6 A History of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona by Peter S. Bennett and Michael R. Kunzmann University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 Western Region National Park Service Department of the Interior San Francisco, Ca. 94102 COOPERATIVE NATIONAL PARK RESOURCES STUDIES UNIT University of Arizona/Tucson - National Park Service The Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit/University of Arizona (CPSU/UA) was established August 16, 1973. The unit is funded by the National Park Service and reports to the Western Regional Office, San Francisco; it is located on the campus of the University of Arizona and reports also to the Office of the Vice-President for Research. Administrative assistance is provided by the Western Arche- ological and Conservation Center, the School of Renewable Natural Resources, and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. The unit's professional personnel hold adjunct faculty and/or research associate appointments with the University. The Materials and Ecological Testing Laboratory is maintained at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center, 1415 N. 6th Ave., Tucson, Arizona 85705. The CPSU/UA provides a multidisciplinary approach to studies in the natural and cultural sciences. Funded projects identified by park management are investigated by National Park Service and university researchers under the coordination of the Unit Leader. Unit members also cooperate with researchers involved in projects funded by non-National Park Service sources in order to obtain scientific information on Park Service lands. -

A History of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, Organ Pipe

SW^> o^n fi-51. Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit ARIZONA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 2 6 A History of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, [ Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona by Peter S. Bennett and Michael R. Kunzmann University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 ON MICROFILM Western Region National Park Service PLEASE RETURN 10: Department of the Interior TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER San Francisco, Ca. 94102 DENVER SERVICE CENTER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COOPERATIVE NATIONAL PARK RESOURCES STUDIES UNIT University of Arizona/Tucson - National Park Service The Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit/University of Arizona (CPSU/UA) was established August 16, 1973. The unit is funded by the National Park Service and reports to the Western Regional Office, San Francisco; it is located on the campus of the University of Arizona and reports also to the Office of the Vice-President for Research. Administrative assistance is provided by the Western Arche- ological and Conservation Center, the School of Renewable Natural Resources, and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. The unit's professional personnel hold adjunct faculty and/or research associate appointments with the University. The Materials and Ecological Testing Laboratory is maintained at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center, 1415 N. 6th Ave., Tucson, Arizona 85705. The CPSU/UA provides a multidisciplinary approach to studies in the natural and cultural sciences. Funded projects identified by park management are investigated by National Park Service and university researchers under the coordination of the Unit Leader. Unit members also cooperate with researchers involved in projects funded by non-National Park Service sources in order to obtain scientific information on Park Service lands. -

The Quitobaquito Desert Pupfish, an Endangered Species Within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument: Historical Significance and Management Challenges

Volume 40 Issue 2 The La Paz Symposium on Transboundary Groundwater Management on the U.S. - Mexico Border Spring 2000 The Quitobaquito Desert Pupfish, An Endangered Species within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument: Historical Significance and Management Challenges Gina Pearson Charles W. Conner Recommended Citation Gina Pearson & Charles W. Conner, The Quitobaquito Desert Pupfish, An Endangered Species within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument: Historical Significance and Management Challenges, 40 Nat. Resources J. 379 (2000). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol40/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. GINA PEARSON & CHARLES W. CONNER* The Quitobaquito Desert Pupfish, An Endangered Species within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument: Historical Significance and Management Challenges ABSTRACT The largest body of water at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is Quitobaquito springs and pond, home to the Quitobaquito desert pupfish (Cyprinodon macularius eremus). The fish was listed as endangered in 1986, along with identification of its critical habitat. The cultural significance of the Quitobaquito area dates to approximately 11,000 B.P. (before present). The natural resource significance is elevated by the existence of other endemic species. The Monument has primarily managed the area for its natural resource significance and critical habitat improvement for decades. Today, a major inventory and monitoring program exists for the pupfish and for water quality and quantity. -

Grasshoppers and Butterflies of the Quitobaquito Management Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

1 2 COOPERATIVE NATIONAL PARK RESOURCES STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 125 Biological Sciences (East) Bldg. 43 Tucson, Arizona 85721 R. Roy Johnson, Unit Leader National Park Senior Research Scientist TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 21 GRASSHOPPERS AND BUTTERFLIES OF THE QUITOBAQUITO MANAGEMENT AREA, ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT, ARIZONA Kenneth J. Kingsley and Richard A. Bailowitz July 1987 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE/UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Contract No. 8100-3-0356 CONTRIBUTION NUMBER CPSU/UA 055/01 3 4 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA ................................................................................................... 2 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 4 DISCUSSION AND RESULTS .................................................................................................... 5 SPECIES ACCOUNTS ..................................................................................................... 8 Grasshoppers .........................................................................................................8 Butterflies ............................................................................................................11 LITERATURE CITED ................................................................................................................ 22 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................... -

National Park Service

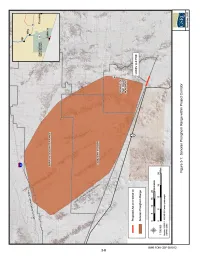

Abstract Between June 24 and 28, 2019, archaeologists with National Park Service’s (NPS) Intermountain Region Archaeology Program (IMRAP) and Southern Arizona Support Office (SOAR) conducted a systematic pedestrian survey of 18.2 km (11.3 mi) of the southern boundary of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (ORPI), a portion of the 3,201 km (1,989 mi) long international border between the United States and Mexico. Over the course of this five-day-long field project the archaeologists surveyed a total of 45.3 ha (112 ac). Cumulatively, they identified, recorded, and mapped 35 isolated occurrences, 20 isolated features, and 5 archaeological sites. This report 1) summarizes the survey findings and 2) offers National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) eligibility recommendations for the 5 newly identified archaeological sites. i Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................... v I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Environmental Setting .............................................................................................................. -

Pima County Is Included in Appendix B

The lesser long-nosed bat is found during the summer within desert grasslands and scrublands. The lesser long-nosed bat spends the day in caves and tunnels and forages at night upon plant nectar and pollen. This bat is an important pollinator of agave, and organ pipe and saguaro cacti (AGFD 2003). Roosting occurs in caves, abandoned buildings, and mines, which are usually located at the base of mountains where food sources are present (AGFD 2003). The lesser long-nosed bat is a seasonal resident of the OPCNM. Roosting sites are located in the OPCNM, but no known roosting sites occur within the project corridor (NPS 2003). The closest location of a known maternity colony to the project corridor would be approximately 15 miles (NPS 2003). 3.6.1.3 Acuña Cactus The candidate status of Acuña cactus was last reviewed on May 11, 2005 (70 FR 24870). Seven populations of Acuña cactus are currently known to exist (Baiza 2007). The species is restricted to well drained knolls and gravel ridges between major washes on substrates, including granite hills and flats and bright red to white andesite, occurring from 1,300 to 2,000 feet in elevation (AGFD 2004). The species requires insect vectors for pollination, with polylectic bee species being the primary agent (AGFD 2004). Dispersal occurs primarily through gravity, and secondarily by wind, rain, and small insects. As a candidate species, the Acuña cactus is not Federally protected, but is protected by the Arizona’s Native Plant Law. Consideration is given to candidate species because of the potential for their listing during project activities, which could require USFWS Section 7 consultation. -

Us Fish and Wildlife Service Species Assessment and Listing Priority

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE SPECIES ASSESSMENT AND LISTING PRIORITY ASSIGNMENT FORM Scientific Name: Kinosternon sonoriense longifemorale Common Name: Sonoyta Mud turtle Lead region: Region 2 (Southwest Region) Information current as of: 05/30/2014 Status/Action ___ Funding provided for a proposed rule. Assessment not updated. ___ Species Assessment - determined species did not meet the definition of the endangered or threatened under the Act and, therefore, was not elevated to the Candidate status. ___ New Candidate _X_ Continuing Candidate ___ Candidate Removal ___ Taxon is more abundant or widespread than previously believed or not subject to the degree of threats sufficient to warrant issuance of a proposed listing or continuance of candidate status ___ Taxon not subject to the degree of threats sufficient to warrant issuance of a proposed listing or continuance of candidate status due, in part or totally, to conservation efforts that remove or reduce the threats to the species ___ Range is no longer a U.S. territory ___ Insufficient information exists on biological vulnerability and threats to support listing ___ Taxon mistakenly included in past notice of review ___ Taxon does not meet the definition of "species" ___ Taxon believed to be extinct ___ Conservation efforts have removed or reduced threats ___ More abundant than believed, diminished threats, or threats eliminated. Petition Information ___ Non-Petitioned _X_ Petitioned - Date petition received: 05/11/2004 90-Day Positive:05/11/2005 12 Month Positive:05/11/2005 Did the -

Sonoyta Mud Turtle Species Status Assessment V2 9-31-17 LITERATURE CITED

Sonoyta Mud Turtle Species Status Assessment V2 9-31-17 LITERATURE CITED Akins, C.M., and T.R. Jones. 2010. Kinosternon Sonoriense (Sonoran Mud Turtle) Predation. Herpetological Review 41:485–486. Archer, S.R. and K.I. Predick. 2008. Climate change and ecosystems of the southwestern United States. Rangelands 30:23–28. Bennett, P.S., and M.R. Kunzmann. 1989. A history of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Arizona, Technical Report 26. 77pp. Bolster, B.C. 1990. Five year status report for desert pupfish, Cyprinodon macularius macularius. California Department of Fish and Game, Inland Fisheries Division, Endangered Species Project, Rancho Cordova, CA. Breshears, D. D., N. S. Cobb, P. M. Rich, K. P. Price, C. D. Allen, R. G. Balice, W. H. Romme, J. H. Kastens, M. L. Floyd, J. Belnap, J. J. Anderson, O. B. Myers, and C. W. Meyers. 2005. Regional vegetation die-off in response to global-change-type drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA (PNAS) 102(42):15144–48. Brown, B. 1991. Land use trends surrounding Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Technical Report 39, Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit, School of Renewable Natural Resources, The University of Arizona, Tucson. 65pp. Brusca, R.C. 2017. A brief geologic history of northwestern Mexico. Version date 23 April 2017. Unpublished Report. 99pp. Carroll, C., R. J. Fredrickson, , and R.C. Lacy. 2012. Developing metapopulation connectivity criteria from genetic and habitat data to recover the endangered Mexican wolf. Conservation Biology 28:76–86. Carruth, R.L. -

The Quitobaquito Desert Pupfish, an Endangered Species Within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument: Historical Significance and Management Challenges

GINA PEARSON & CHARLES W. CONNER* The Quitobaquito Desert Pupfish, An Endangered Species within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument: Historical Significance and Management Challenges ABSTRACT The largest body of water at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is Quitobaquito springs and pond, home to the Quitobaquito desert pupfish (Cyprinodon macularius eremus). The fish was listed as endangered in 1986, along with identification of its critical habitat. The cultural significance of the Quitobaquito area dates to approximately 11,000 B.P. (before present). The natural resource significance is elevated by the existence of other endemic species. The Monument has primarily managed the area for its natural resource significance and critical habitat improvement for decades. Today, a major inventory and monitoring program exists for the pupfish and for water quality and quantity. Location of the area next to the international border and easy access makes the pupfish and its habitat vulnerable to a number of potential threats such as introduction of exotic species, chemical contamination, human use of the area, and water use for agricultural, domestic, and development purposes in Mexico. Although there is no immediate threat to the Quitobaquito springs or pupfish from groundwater use in Mexico, the potential does exist should water levels drop significantly. There are a number of intranational and international laws and policies that support protection of the Quitobaquito pupfish, and the pupfish in the Sonoyta River, which lies within the Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve in Mexico (Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument's sister park). I. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (Organ Pipe), encom- passing 133,598 hectares, was established by Presidential Proclamation No. -

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument History of Ranching

THE HISTORY OF RANCHING AT ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT THEMATIC CONTEXT STUDY ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT Preservation Studies Program College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture The University of Arizona In conjunction with: Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (DS-CESU) September 2009 PROJECT INFORMATION This project was carried out between the National Park Service (NPS) and the University of Arizona (UA) through a Joint Ventures Agreement administered by the Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (DS-CESU). Principal Investigator R. Brooks Jeffery Preservation Studies College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture The University of Arizona Report Author Robin Pinto Graduate Student, Renewable & Natural Resources Organ Pipe Cactus NM Lee Baiza, Superintendent Mark Sturm, Resource Manager Joe Toumey, Vanishing Treasures Archaeologist DS-CESU William (Pat) O’Brien, Cultural Resources Liaison Project References Cooperative Agreement No. H1200050003 Task Agreement No. J1242060042 Project Number UAZDS-211 UA Account No. 358650 Cover Photo: “Pozo Salado watering tanks and corral. Cholla joint hangs from lower lip of cow.” Unknown date and photographer. Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Archives, #2186. CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 1 A Thematic Introduction Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Political and Environmental Setting 2. Early Ranching in the Southwest and Arizona 6 The Growth of the Cattle Industry in the Southwest The End of the Open Range Ranching System: Environmental Causes Environmental Consequences of Drought and Overgrazing 3. The History of the Public Domain and Range Rights 11 Dispensing Public Lands: the Homestead Acts The Public Domain: Free Land for the Taking The Code of the West and Range Rights Early Federal Land Reservations from the Public Domain 4. -

70-6668 SIMMONS, Norman Montgomery, 1934- the SOCIAL ORGANIZATION, BEHAVIOR, and ENVIRONMENT of the DESERT BIGHORN SHEEP on the CABEZA PRIETA GAME RANGE, ARIZONA

THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION, BEHAVIOR, AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE DESERT BIGHORN SHEEP ON THE CABEZA PRIETA GAME RANGE, ARIZONA Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Simmons, Norman Montgomery, 1934- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:06:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/287436 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6668 SIMMONS, Norman Montgomery, 1934- THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION, BEHAVIOR, AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE DESERT BIGHORN SHEEP ON THE CABEZA PRIETA GAME RANGE, ARIZONA. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Biology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION, BEHAVIOR, AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE DESERT BIGHORN SHEEP ON THE CABEZA PRIETA GAME RANGE, ARIZONA by Norman Montgomery Simmons A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN WILDLIFE BIOLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1969 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Norman Montgomery Simmons entitled ^le Social Organization, Behavior, and Environment of the Desert Bighorn Sheep on the Cabeza Prieta Game Range, Arizona. be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy tLf k L..SL- iL Dissertation Director After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* /U.