Bricolage Thinking and Matua Narratives on the Andaman Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

700 032 September 7, 2021 a D M I S S I O N B.A

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY KOLKATA – 700 032 September 7, 2021 A D M I S S I O N B.A. (HONOURS) COURSE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE SESSION 2021 - 2022 The Lists are provisional and are subject to: i. fulfilling the eligibility criteria as notified earlier. ii. verification of the equivalence of marks/degrees from other Boards/Councils to those of the West Bengal council of Higher Secondary Education /Other equivalent Board/Council, wherever applicable. iii. correction in the merit position due to error, if any. All admissions are provisional. As per the order of Govt. of West Bengal [order no: 706-Edn(CS)/10M-95/14 dated 13/7/2021], all the original documenmts of applicants will be verified when they report for classes at University campus. Provisional admission of a candidate will stand cancelled if the documents are found not in conformity with the declaration in the forms submitted on-line. If at the time of document verification, it is found by the university authority that a student does not satisfy the eligibility criteria, s/he will not be considered for admission, even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission. a student does not have completed result at +2 level, his/her application shall be cancelled even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission. a candidate has already graduated from a college with a Bachelors degree, her/his application shall be cancelled even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission, since s/he cannot enrol herself/himself for another Bachelors degree course. Those candidates who have -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

Chief Engineer (HQ.), Public Works Directorate Government of West

Chief Engineer (HQ.), Io NABANNA.8th Floor. Public Works Directorate 325, Sarat Chatterjee Road, Shibpur, Government of West Bengal Howrah -711102 Tel No: 033-2214-3619, Fax No: 033-2214-3343 emailld:[email protected] No. 1227/CE(HQ)/PWD Date: 02.09.2020 ORDER The following noted Junior Engineers (Civil) under the P.W.D.• as tabulated below are hereby transferred from their present place of posting and on such transfer they are posted at the office as indicated against their names. with immediate effect and until further order. T.AID.A. is admissible as per rule. SI. Name Present Place of Posting. Posting on Tranfer. No. Estimator under the office of the Barrackpore Sub-Division- II, under I Shri Sanjoy Basu. Superintendent, Governor's Esate, Barrackpore Division, P.W.Dte. W.B. Kolkata Raj Bhavan Sub-Division Barrackpore Sub-Division- II, Shri Tarun Kumar 2 under Superintendent, Governor's under Barrackpore Division, Sharma Sarkar. Esate, W.B. P.W.Dte. Bidhannagar West Sub-Division-1Il Shri Ashim Estimator,Birbhum Division, 3 under Bidhannagar West Sub- Bhowmik. P.W.Dte. Division. P.W.Dte. Durgapur Sub Division under Shri Basudev Western Circle, Social Sector, 4 Asansol Division, Social Chandra. P.W.Dte. Sector,P. W.Dte. Bidhannagar West Sub-Division-1Il Shri Manab Estimator, Asansol Division, Social 5 under Bidhannagar West Sub- Mondal. Sector, P.W.Dte. Division. P.W.Dte. Shri Swapan Kumar Estimator, Murshidabad Division, Office of the Chief Engineer, 6 Bera. Social Sector, P.W.Dte. Planning, P.W.Dte. Shri Dilip Office of the Chief Engineer, Estimator, Murshidabad Division, 7 Karmakar. -

Download the File As PDF Format

WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES VOLUME – I (Containing 1 st , 2 nd & 3 rd Reports) FIRST REPORT : Name of the Class INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. KAPALI ….. 2. BAISHYA KAPALI ….. 3. KURMI ….. 4. SUTRADHAR ….. 5. KARMAKAR ….. 6. KUMBHAKAR ….. 7. SWARNAKAR ….. 8. TELI ….. 9. NAPIT 10. YOGI-NATH ….. 11. GOALA GOPE ….. 12. MOIRA-MODAK (HALWAI) ….. 13. BARUJIBI ….. 14. SATCHASI ….. SECOND REPORT : Name of the Class INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. MALAKAR ….. 2. TANTI ….. 3. KANSARI ….. 4. SHANKHAKAR ….. 5. KOERI / KOIRI ….. 6. RAJU ….. 7. TAMBOLI / TAMALI ….. 8. NAGAR ….. 9. KARANI ….. 10. DHANUK ….. 11. SARAK ….. 12. JOLAH (ANSARI-MOMIN) ….. THIRD REPORT : INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. RONIWAR ….. 2. KOSTA / KOSTHA ….. 3. CHRISTIANS CONVERTED FROM SCHEDULED CASTES ….. WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES REPORT – I Representations have reached the West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes from various classes of citizens for inclusion in the lists of Backward Classes of the State. The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes has been set up by the Act of the State Legislature – “West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act, 1993 (West Bengal Act I of 1993)”. The Act provides “it is expedient to constitute a State Commission for Backward Classes other than the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and to provide matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”; and accordingly, the Act called “The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act” (hereinafter referred to as the Act) came to be enacted. In terms of the provisions contained in Section 3 of the Act the State Government has constituted this body to be known as “The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes“ (which will hereinafter be referred to as the Commission) to exercise the powers conferred on and to perform the functions assigned to the commission under the Act. -

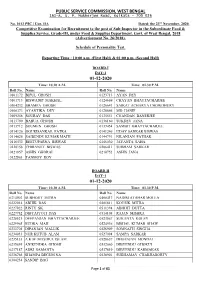

Schedule of Personality Test to the Post of Sub-Inspector in The

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. Mukherjee Road, Kolkata – 700 026 No. 1013 PSC / Con. IIA Dated: the 23rd November, 2020. Competitive Examination for Recruitment to the post of Sub-Inspector in the Subordinate Food & Supplies Service, Grade-III, under Food & Supplies Department, Govt. of West Bengal, 2018 (Advertisement No. 26/2018). Schedule of Personality Test. Reporting Time : 10:00 a.m. (First Half) & 01:00 p.m. (Second Half) BOARD-I DAY-1 01-12-2020 Time: 10.30 A.M. Time: 01.30 P.M. Roll No. Name Roll No. Name 0101172 BIPUL GHOSH 0123713 AYAN DEY 0101713 BISWADIP MAKHAL 0124669 CHAYAN BHATTACHARJEE 0104232 SHAMPA GHOSH 0126641 SAIKAT ACHARYA CHOWDHURY 0106373 AYANTIKA DEY 0126666 MD HANIF 0109256 SOURAV DAS 0135551 CHANDAN BANERJEE 0113799 BABUA GHOSH 0136160 SUKDEV JANA 0113912 SOUMEN GHOSH 0137454 SAMBIT BHATTACHARJEE 0114126 GOURISANKAR PATRA 0141246 UDAY SANKAR BISWAS 0114626 SAIBENDU KUMAR MAITI 0144791 NILANJAN PATHAK 0116532 REETUPARNA BISWAS 0146030 JAYANTA SAHA 0120158 CHIRANJIT BISWAS 0206411 SUBHAM SARKAR 0121857 ASHIS GHORAI 0210752 ASHIS JANA 0122861 TANMOY ROY BOARD-II DAY-1 01-12-2020 Time: 10.30 A.M. Time: 01.30 P.M. Roll No. Name Roll No. Name 0214902 SUBHOJIT MITRA 0408417 NADIM ATAHAR MOLLA 0222014 ABHIK DAS 0501811 KOUSIK MITRA 0227022 RINTU SK 0511394 ABHIJIT DUTTA 0227782 DIBYAJYOTI DAS 0514108 RAJAN MISHRA 0228521 DEEPANJAN BHATTACHARJEE 0523567 SUKANTA KOLEY 0229965 RUDRA MAJI 0524936 BISHAL KUMAR SHAW 0233705 DIPANJAN MALLIK 0526909 SOMNATH SINGHA 0234033 NUR KUTUB ALAM 0527094 SAMPA SARKAR 0235133 A K M MASIDUL ISLAM 0528637 DEBANJAN MONDAL 0235691 ANIRENDRA GHOSH 0532060 DIBYENDU GHORUI 0237187 ADRI SAMANTA 0537619 DIBYENDU KARMAKAR 0238766 SHAMPA BEGUM NA 0538901 SUBHAMAY CHAKRABORTY 0304234 SANDIP BAG Page 1 of 61 PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

DOCUMENTO De TRABAJO DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO

InstitutoINSTITUTO de Economía DE ECONOMÍA TRABAJO de DOCUMENTO DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO 423 2012 Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak, Jeanne Lafortune. www.economia.puc.cl • ISSN (edición impresa) 0716-7334 • ISSN (edición electrónica) 0717-7593 Versión impresa ISSN: 0716-7334 Versión electrónica ISSN: 0717-7593 PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE INSTITUTO DE ECONOMIA Oficina de Publicaciones Casilla 76, Correo 17, Santiago www.economia.puc.cl MARRY FOR WHAT? CASTE AND MATE SELECTION IN MODERN INDIA Abhijit Banerjee Esther Duflo Maitreesh Ghatak Jeanne Lafortune* Documento de Trabajo Nº 423 Santiago, Marzo 2012 * [email protected] INDEX ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION 1 2. MODEL 5 2.1 Set-up 5 2.2 An important caveat: preferences estimation with unobserved attributes 8 2.3 Stable matching patterns 8 3. SETTING AND DATA 13 3.1 Setting: the search process 13 3.2 Sample and data collection 13 3.3 Variable construction 14 3.4 Summary statistics 15 4. ESTIMATING PREFERENCES 17 4.1 Basic empirical strategy 17 4.2 Results 18 4.3 Heterogeneity in preferences 20 4.4 Do these coefficients really reflect preferences? 21 4.4.1 Strategic behavior 21 4.4.2 What does caste signal? 22 4.5 Do these preferences reflect dowry? 24 5. PREDICTING OBSERVED MATCHING PATTERNS 24 5.1 Empirical strategy 25 5.2 Results 27 5.2.1 Who stays single? 27 5.2.2 Who marries whom? 28 6. THE ROLE OF CASTE PREFERENCES IN EQUILIBRIUM 30 6.1 Model Predictions 30 6.2 Simulations 30 7. -

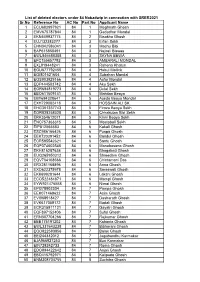

Sr.No Reference No AC No Part No Applicant Name 1 ECU682997921

List of deleted electors under 84 Nabadwip in connection with SRER2021 Sr.No Reference No AC No Part No Applicant Name 1 ECU682997921 84 1 Meghnath Ghosh 2 EMV675787844 84 1 Gadadhar Mandal 3 EKN549937774 84 2 Bisakha Ghosh 4 EUJ132383277 84 3 Erfan Sekh 5 EHN342586041 84 3 Machu Bibi 6 EAP615850491 84 3 Najirali Biswas 7 EWL846688308 84 3 SAYNA BEWA 8 EFC155657792 84 3 AMBARALI MONDAL 9 EXL819448241 84 3 Rahena Khatun 10 EGU677792455 84 4 Habul Mollick 11 EQI801621604 84 4 Subahan Mondal 12 EQS903929166 84 4 Asfar Mondal 13 EDP444503742 84 4 Aku Sekh 14 EGR694819773 84 4 Dulal Sekh 15 EBO611509141 84 5 Mahitan Beoya 16 EBY694328641 84 5 Aseda Beoya Mondal 17 EXH729082418 84 5 HOSSAIN ALI SK 18 EHG301357743 84 5 Firoza Beoya Sekh 19 EOR828258028 84 5 Chhakutan Bibi Sekh 20 ERK354612071 84 5 Kinni Beoya Sekh 21 ENC757363315 84 5 Mastabali Sekh 22 EIP812565583 84 6 Kakali Ghosh 23 ESC986166426 84 6 Puspa Ghosh 24 EEK720391452 84 6 Bandul Ghosh 25 ECR595542621 84 6 Santu Ghosh 26 EQP374602546 84 6 Manabasana Ghosh 27 EKH816287634 84 6 Bhagabati Ghosh 28 EUQ265950312 84 6 Shreedam Ghosh 29 EQV704168666 84 6 Chintamani Das 30 ERX281168896 84 6 Anna Ghosh 31 EXO622375978 84 6 Saraswati Ghosh 32 EKK699281644 84 6 Lakshi Ghosh 33 ECO522484871 84 6 Mampi Ghosh 34 EYW921476558 84 6 Nimai Ghosh 35 EPI278902304 84 7 Pampa Ghosh 36 EEK071469622 84 7 Asim Ghosh 37 EVI068918427 84 7 Dasharath Ghosh 38 EVK617059172 84 7 Badali Ghosh 39 ECR315911121 84 7 Gayatri Ghosh 40 EQF897152406 84 7 Sufal Ghosh 41 ERN307704266 84 7 Rajkumar Ghosh 42 EEE175191202 -

REPORT Part - C Vol

Visva-Bharati Santiniketan 731235 INDIA SELF-STUDY REPORT Part - C Vol. 1 Evaluative Report of the Departments Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council 2014 C O N T E N T S SANGIT BHAVANA (INSTITUTE OF MUSIC, DANCE & DRAMA) Rabindra Sangit, Dance and Drama 1 Hindustani Classical Music 44 KALA BHAVANA (INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS ) Painting 70 Sculpture 96 Graphic Art 114 History of Art 136 Design 156 Evaluative Report of the Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance and Drama, 1 Sangit Bhavana Evaluative Report of the Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance and Drama 1. Name of the Department: Rabindra Sangit, Dance and Drama, Sangit-Bhavana (Institute of Music, Dance and Drama), Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan 2. Year of establishment: 1933 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the University? Yes. 4. Names of programmes offered (UG, PG, M.Phil., Ph.D., integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : a) B.Mus b) M.Mus c) M.Phil d) Ph.D e) D.Litt f) One Year Course for Foreign Students in all subjects under Sangit Bhavana, g) Two Year Certificate Course. 5. Interdisciplinary programmes and departments involved: The faculty and students regularly perform programmes with the different departments of the Bhavanas at the University level. The Sangit Bhavana constantly is keeping in touch with Rabindra Bhavana towards organizing seminars, conferences, programmes at the National level. The Bhavana also undertakes collaborative research programmes. Students are offered courses like Tagore Studies, Environmental Studies with the other departments of Visva-Bharati at the UG level. At the PG level, the subject Acoustics is being offered by the Physics department. -

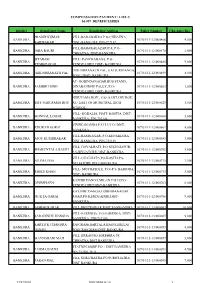

Compensation Payment : List-5 66,059 Beneficiaries

COMPENSATION PAYMENT : LIST-5 66,059 BENEFICIARIES District Beneficiary Name Beneficiary Address Policy Number Chq.Amt.(Rs.) PRADIP KUMAR VILL-BARABAKRA P.O-CHHATNA, BANKURA 107/01/11-12/000466 4,500 KARMAKAR DIST-BANKURA, PIN-722132 VILL-BARAKALAZARIYA, P.O- BANKURA JABA BAURI 107/01/11-12/000476 2,000 CHHATNA, DIST-BANKURA, SITARAM VILL- PANCHABAGA, P.O- BANKURA 107/01/11-12/000486 9,000 KUMBHAKAR KENDUADIHI, DIST- BANKURA, HIRENDRANATH PAL, KATJURIDANGA, BANKURA HIRENDRANATH PAL 107/01/11-12/000499 8,000 POST+DIST- BANKURA. AT- GOBINDANAGAR BUS STAND, BANKURA SAMBHU SING DINABANDHU PALLY, P.O- 107/01/11-12/000563 1,500 KENDUADIHI, DIST- BANKURA, NIRUPAMA ROY , C/O- SANTANU ROU, BANKURA SMT- NIRUPAMA ROY AT- EAST OF MUNICIPAL HIGH 107/01/11-12/000629 5,000 SCHOOL, VILL- KODALIA, POST- KOSTIA, DIST- BANKURA MONGAL LOHAR 107/01/11-12/000660 5,000 BANKURA, PIN-722144. VIVEKANANDA PALLI, P.O+DIST- BANKURA KHOKAN GORAI 107/01/11-12/000661 8,000 BANKURA VILL-RAMNAGAR, P.O-KENJAKURA, BANKURA AJOY KUMBHAKAR 107/01/11-12/000683 3,000 DIST-BANKURA, PIN-722139. VILL-GOYALHATI, P.O-NIKUNJAPUR, BANKURA SHAKUNTALA BAURI 107/01/11-12/000702 3,000 P.S-BELIATORE, DIST-BANKURA, VILL-GUALHATA,PO-KOSTIA,PS- BANKURA NILIMA DAS 107/01/11-12/000715 1,500 BELIATORE,DIST-BANKURA VILL- MOYRASOLE, P.O+P.S- BARJORA, BANKURA RINKU KHAN 107/01/11-12/000743 3,000 DIST- BANKURA, KAJURE DANGA,MILAN PALLI,PO- BANKURA DINESH SEN 107/01/11-12/000763 6,000 KENDUADIHI,DIST-BANKURA KATJURE DANGA,GOBINDANAGAR BANKURA MUKTA GARAI ROAD,PO-KENDUADIHI,DIST- 107/01/11-12/000766 9,000 BANKURA BANKURA ASHISH KARAK VILL BHUTESWAR POST SANBANDHA 107/01/12-13/000003 10,000 VILL-SARENGA P.O-SARENGA DIST- BANKURA SARADINDU HANSDA 107/01/12-13/000007 9,000 BANKURA PIN-722150 KARTICK CHANDRA RAJGRAM(BARTALA BASULIMELA) BANKURA 107/01/12-13/000053 8,000 HENSH POST RAJGRAM DIST BANKURA VILL JIRRAH PO JOREHIRA PS BANKURA MAYNARANI MAJI 107/01/12-13/000057 5,000 CHHATNA DIST BANKURA STATION MORE PO + DIST BANKURA BANKURA PADMA BAURI 107/01/12-13/000091 4,500 PIN 722101 W.B.