Chapter 22 Urfi Urban Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Analysis of Yamuna River

Journal of Materials Science & Surface Engineering, 6(6): 905-908 ISSN (Online): 2348-8956; 10.jmsse/2348-8956/6-6.6 Biological analysis of Yamuna River Pooja Upadhyay · Arushi Saxena · Pammi Gauba Department of Biotechnology, Jaypee Institute of Information Technology, Noida A-10, Sector-62, Noida, Uttar Pradesh-201307. ARTICLE HISTORY ABSTRACT Received 30-03-2019 Water pollution is a very common cause of major health problems across the globe. The most common and Revised 01-09-2019 widespread health risk associated with drinking water is contamination. The pathogenic agents involved Accepted 06-09-2019 include bacteria, viruses, and protozoa, which may cause diseases that vary in severity from mild Published 01-12-2019 gastroenteritis to severe and sometimes fatal diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis, or typhoid fever, most of them are widely distributed throughout the world. Biological testing methods are progressively often used for KEYWORDS determining the surface water quality. In the biological analysis of the water samples using methods like, Biological testing most probable number (MPN) method, glutamate starch phenol red agar and hektoen enteric agar, we Contamination observed various organisms like Coliform bacteria, Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Salmonella, and Shigella, Harmful organism which are harmful for consumption of population to be present in the river water. The biological methods Water pollution are used for analyzing water quality involves collection, counting and identification of micro organisms, measurement of metabolic activity rates, and processing and interpretation of biological data. In this paper, we have done a comparative analysis of microbes present in samples collected from different places and their impact on water quality. -

Current Condition of the Yamuna River - an Overview of Flow, Pollution Load and Human Use

Current condition of the Yamuna River - an overview of flow, pollution load and human use Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal, TERI University Introduction Yamuna is the sub-basin of the Ganga river system. Out of the total catchment’s area of 861404 sq km of the Ganga basin, the Yamuna River and its catchment together contribute to a total of 345848 sq. km area which 40.14% of total Ganga River Basin (CPCB, 1980-81; CPCB, 1982-83). It is a large basin covering seven Indian states. The river water is used for both abstractive and in stream uses like irrigation, domestic water supply, industrial etc. It has been subjected to over exploitation, both in quantity and quality. Given that a large population is dependent on the river, it is of significance to preserve its water quality. The river is polluted by both point and non-point sources, where National Capital Territory (NCT) – Delhi is the major contributor, followed by Agra and Mathura. Approximately, 85% of the total pollution is from domestic source. The condition deteriorates further due to significant water abstraction which reduces the dilution capacity of the river. The stretch between Wazirabad barrage and Chambal river confluence is critically polluted and 22km of Delhi stretch is the maximum polluted amongst all. In order to restore the quality of river, the Government of India (GoI) initiated the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) in the1993and later YAPII in the year 2004 (CPCB, 2006-07). Yamuna river basin River Yamuna (Figure 1) is the largest tributary of the River Ganga. The main stream of the river Yamuna originates from the Yamunotri glacier near Bandar Punch (38o 59' N 78o 27' E) in the Mussourie range of the lower Himalayas at an elevation of about 6320 meter above mean sea level in the district Uttarkashi (Uttranchal). -

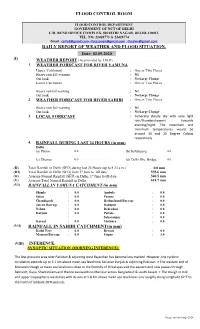

Flood Control Room Daily Report

FLOOD CONTROL ROOM FLOOD CONTROL DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF NCT OF DELHI L.M. BUND OFFICE COMPLEX, SHASTRI NAGAR, DELHI-110031. TEL. NO. 22428773 & 22428774 Email : [email protected], [email protected] , [email protected] DAILY REPORT OF WEATHER AND FLOOD SITUATION. Date: 02.09.2020 (I) WEATHER REPORT (As provided by I.M.D) 1. WEATHER FORECAST FOR RIVER YAMUNA Upper Catchment : One or Two Places Heavy rain fall warning : Nil Out look : No Large Change Lower Catchment : One or Two Places Heavy rainfall warning : Nil Out look : No Large Change 2. WEATHER FORECAST FOR RIVER SAHIBI : One or Two Places Heavy rain fall warning : Nil Out look : No Large Change 3. LOCAL FORECAST : Generally cloudy sky with very light rain/thundershowers towards evening/night. The maximum and minimum temperatures would be around 35 and 25 Degree Celsius respectively. 4. RAINFALL DURING LAST 24 HOURS (in mm) Delhi (a) Palam : 0.0 (b) Safdarjung 0.0 (c) Dhansa : 0.0 (d) Delhi Rly. Bridge 0.0 (II) Total Rainfall in Delhi (SFD) during last 24 Hours (up to 8.30 a.m.) 0.0 mm (III) Total Rainfall in Delhi (SFD) from 1st June to till date 555.6 mm (iv) Average Normal Rainfall (SFD) in Delhi, 1st June to till date 540.5 mm (V) Average Total Normal Rainfall in Delhi. 618.7 mm (VI) RAINFALL IN YAMUNA CATCHMENT (in mm) Shimla : 0.0 Ambala : 0.0 Solan : 0.0 Paonta : 0.0 Chandigarh : 0.0 Hathni kund Barrage : 0.0 Jateon Barrage : 0.0 Dadupur : 0.0 Nahan : 0.0 Dehradun : 0.0 Haripur : 0.0 Patiala : 0.0 : Saharanpur : 0.0 Karnal : 0.0 Mathura : 0.0 (VII) RAINFALL IN SAHIBI CATCHMENT(in mm) Dadri Toye : 0.0 Rewari : 0.0 Massani Barrage : 0.0 Jaipur : 3.0 (VIII) INFERENCE: SYNOPTIC SITUATION (MORNING INFERENCE): The low-pressure area over Pakistan & adjoining west Rajasthan has become less marked. -

Spread-Wing Postures and Their Possible Functions in the Ciconiidae

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY Von. 88 Oc:roBE'a 1971 No. 4 SPREAD-WING POSTURES AND THEIR POSSIBLE FUNCTIONS IN THE CICONIIDAE M. P. KAI-IL IN two recent papers Clark (19'69) and Curry-Lindahl (1970) have reported spread-wingpostures in storks and other birds and discussed someof the functionsthat they may serve. During recent field studies (1959-69) of all 17 speciesof storks, I have had opportunitiesto observespread-wing postures. in a number of speciesand under different environmentalconditions (Table i). The contextsin which thesepostures occur shed somelight on their possible functions. TYPES OF SPREAD-WING POSTURES Varying degreesof wing spreadingare shownby at least 13 species of storksunder different conditions.In somestorks (e.g. Ciconia nigra, Euxenuragaleata, Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis, and ]abiru mycteria) I observedno spread-wingpostures and have foundno referenceto them in the literature. In the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) I observedonly a wing-droopingposture--with the wings held a short distanceaway from the sidesand the primaries fanned downward--in migrant birds wetted by a heavy rain at NgorongoroCrater, Tanzania. Other species often openedthe wingsonly part way, in a delta-wingposture (Frontis- piece), in which the forearmsare openedbut the primariesremain folded so that their tips crossin front o.f or below the. tail. In some species (e.g. Ibis leucocephalus)this was the most commonly observedspread- wing posture. All those specieslisted in Table i, with the exception of C. ciconia,at times adopted a full-spreadposture (Figures i, 2, 3), similar to those referred to by Clark (1969) and Curry-Lindahl (1970) in severalgroups of water birds. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Myanmar

Avibase Page 1of 30 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Myanmar 2 Number of species: 1088 3 Number of endemics: 5 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of introduced species: 1 6 7 8 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Myanmar. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=mm [23/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Are You Suprised ? F…

1.0 INTRODUCTION The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 has been aimed to fulfill the water quality requirement of designated-best-uses of all the natural aquatic resources. Loss of bio-diversity on account of degradation of habitat has become the cause of major concern in recent years. Central Pollution Control Board, while executing the nation wide responsibility for water quality monitoring and management has established water quality monitoring network in the country. The Water Quality Monitoring Network constitutes 784 monitoring stations located on various water bodies all over the country. However, wetland areas have not been included as part of regular water quality monitoring network in the country. Keeping in view the importance of water quality of wetland areas, Central Pollution Control Board has initiated studies on Bio-monitoring of selected wetlands in wildlife habitats of the country. Bio monitoring of wetlands in wild life sanctuaries has been considered as most suitable measure to evaluate the health of wildlife ecosystem. Further, the monitoring of environmental variables will be immensely helpful in protecting and restoring the ecological status in these threatened habitats. 2.0 CPCB’S INITIATIVES FOR BIO-MONITORING OF WETLANDS Under the Indo-Dutch collaborative project, the development of bio- monitoring methodology for Indian river water quality evaluation was initiated during 1988. The Central Pollution Control Board carried out a pilot study on the River Yamuna for a selected stretch from Delhi upstream to Etawah downstream. The main objective of this study was to formulate strategic methods, which can be accepted in scientific and legislative framework for water quality evaluation. -

India: Tigers, Taj, & Birds Galore

INDIA: TIGERS, TAJ, & BIRDS GALORE JANUARY 30–FEBRUARY 17, 2018 Tiger crossing the road with VENT group in background by M. Valkenburg LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: TIGERS, TAJ, & BIRDS GALORE January 30–February 17, 2018 By Machiel Valkenburg This tour, one of my favorites, starts in probably the busiest city in Asia, Delhi! In the afternoon we flew south towards the city of Raipur. In the morning we visited the Humayan’s Tomb and the Quitab Minar in Delhi; both of these UNESCO World Heritage Sites were outstanding, and we all enjoyed them immensely. Also, we picked up our first birds, a pair of Alexandrine Parakeets, a gorgeous White-throated Kingfisher, and lots of taxonomically interesting Black Kites, plus a few Yellow-footed Green Pigeons, with a Brown- headed Barbet showing wonderfully as well. Rufous Treepie by Machiel Valkenburg From Raipur we drove about four hours to our fantastic lodge, “the Baagh,” located close to the entrance of Kanha National Park. The park is just plain awesome when it comes to the density of available tigers and birds. It has a typical central Indian landscape of open plains and old Sal forests dotted with freshwater lakes. In the early mornings when the dew would hang over the plains and hinder our vision, we heard the typical sounds of Kanha, with an Indian Peafowl displaying closely, and in the far distance the song of Common Hawk-Cuckoo and Southern Coucal. -

A Preliminary Assessment of Avifaunal Diversity of Nawabganj Bird Sanctuary, Unnao, Uttar Pradesh

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 9, Issue 4 Ver. II (Apr. 2015), PP 81-91 www.iosrjournals.org A Preliminary Assessment of Avifaunal Diversity of Nawabganj Bird Sanctuary, Unnao, Uttar Pradesh Adesh Kumar, Amita Kanaujia, Sonika Kushwaha and Akhilesh Kumar Biodiversity & Wildlife Conservation Lab, Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow- 226007 Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract: Avifaunal Diversity is one of the most important ecological indicators to evaluate the status of habitats. Birds are the crucial animal group of an ecosystem which maintains a trophic level. Therefore, detail study on avifauna and their ecology is important to protect them. They are one of the biological control tools to control pests in gardens, on farms, and other places. They abet in the pollinization of plants. Birds are also good seed dispersal.The study was performed in Nawabganj Bird Sanctuary (NBS) during January 2013 to March 2014. NBS covers the 224.60 hectare area and provides breeding grounds to multiple populations of flora and fauna. Surveys were carried out seasonally and observations were made along line transects with the aid of 10x50 binoculars and Canon EOS 1000 D SLR camera. The Avifaunal assessment of NBS includes 150 species of birds belonging to 17 orders and 46 families. The order Passeriformes has maximum 51 species of birds. Purple moorhen and lesser whistling duck are the most abundant residential species in the NBS. Habitat wise classification reveals that 43.33% of birds were dependent on aquatic habitat (65) i.e. -

E-Flow) in River Yamuna

Environmental flow (E-Flow) in river Yamuna Context: The Hon’ble NGT in its judgment dated 13 January 2015 and through subsequent directions in OA No 6 of 2012 and 300 of 2013 given directions for the maintenance of requisite environmental flow in river Yamuna downstream of the barrage at Hathnikund in Haryana and at Okhla in Delhi so that there is enough fresh water flowing in the river till Agra for restoration of the river’s ecological functions. The Hon’ble Supreme Court had in W.P. ( C ) 537 of 1992 directed on 14 May 1999, that “a minimum flow of 10 cumecs (353 cusec) must be allowed to flow throughout the river Yamuna”. The report of the three member committee of MoWR, RD and GR on Assessment of Environmental Flows (E-Flows) has in March 2015 determined scientifically that E Flows as % of 90% dependable virgin flow at downstream Pashulok Barrage, Rishikesh on river Ganga should be 65.80%. It may be noted that the situation of river Yamuna at the Hathnikund barrage in Haryana is comparable to the situation at Rishikesh on river Ganga. In addition river Ganga at Rishikesh carries far more virgin flow in it as compared to leaner river Yamuna at Hathnikund. E – Flow in river Yamuna In view of the above it has been estimated that the E Flow in river Yamuna downstream of the barrage at Hathnikund should be no less than 2500 cusec (around 70% of the average minimum virgin flow of 3500 cusec reported at Hathnikund barrage during the leanest month of January). -

Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI, DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. †1015 ANSWERED ON 27.06.2019 CLEANLINESS OF YAMUNA RIVER †1015. SHRI MANOJ TIWARI Will the Minister of JAL SHAKTI be pleased to state: (a) the steps being taken by the Government to maintain cleanliness of Yamuna river flowing through the district headquarters, cities and industrial areas in the country; (b) whether the Government is going to make new provisions in this regard; and (c) if so, the details of the strategy being formulated for the same? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR JAL SHAKTI & SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (SHRI RATTAN LAL KATARIA) (a) to (c) The cleaning of Rivers is a continuous process and this Ministry is supplementing the efforts of the States for checking the rising level of pollution of river Yamuna, a tributary of River Ganga, by providing financial assistance to different States of Haryana, Delhi and Uttar Pradesh in phased manner since 1993 under the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP). State-wise figure for numbers of project sanctioned and the estimated cost is as under:- Name of States Number of Projects Estimated Costs sanctioned (Rs. in crores). Himachal Pradesh 1 11.57 Haryana 2 217.87 Delhi 14 2421.00 Uttar Pradesh 8 1948.00 Total 25 4,598.44 In addition following initiatives have also been taken for cleanliness of river Yamuna: To remove the floating trash from the river surface trash skimmers have been deployed at Mathura & Delhi. A study for assessment of environmental flows in river Yamuna (from Hathinkund to Okhla barrage) is being carried out by National Institute of Hydrology, Rorkee. -

Chief Engineer (Yamuna) Okhla, New Delhi- 110 025

PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT Project for Construction of Rubber Dam at 1.5 K.M Downstream of Taj Mahal on River Yamuna in Agra City Submitted to: The Ministry of Environment Forest & Climate Change, New Delhi April 2019 Submitted by: Chief Engineer (Yamuna) Okhla, New Delhi- 110 025 Irrigation and Water Resource Department, Uttar Pradesh PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 3 1.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................. 4 1.4 LOCATION & CONNECTIVITY............................................................................................. 5 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................. 8 2.1 LAND REQUIREMENT ...................................................................................................... 12 2.2 RAW MATERIAL REQUIREMENT ..................................................................................... 13 2.3 MANPOWER REQUIREMENT .......................................................................................... 13 2.4 WATER REQUIREMENT .................................................................................................. -

Pollution Study of River Yamuna: the Delhi Story

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2015): 78.96 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Pollution Study of River Yamuna: The Delhi Story Keshav Sharma School of Civil and Chemical Engineering, VIT University, Vellore, Tamil Nadu Abstract: Water pollution may be defined as the presence of one or more contaminants or combinations thereof in such quantities and of such durations in the water tend to be injurious to human, animal or plant life,(aquatic life) or property, or which unreasonably interferes with the comfortable enjoyment of life or property. In easier words, it is the contamination of water bodies like lakes, rivers, ponds, seas, oceans and even groundwater. This is due to discharge of environmental pollutants or effluents into water bodies without treatment. Water pollution affects the entire biosphere, including not only the individual species but also their natural biological communities. It results in the death of much of the aquatic life residing inside the contaminated water body. It also leads to various diseases like cholera, dysentery, diarrhea, malaria, dengue, chickingunia, etc. and even fatal in some cases if that water is consumed without treatment. Keywords: Water pollution, Delhi Segment, Yamuna, Treatment, Aquatic life, Tajewala Barrage, Confluence, Tributary, BOD, COD, DO 1. Introduction Eutrophicated Segmentand the Diluted Segment are the respective five segments River Yamuna or Jamuna is the longest and second largest tributary of river Ganga in northern India. It originates from A. The Himalayan Segment Yamunotri glacier at a height of 6,387 metres (20,955 feet) The Himalayan Segment, covering 172 kilometres(107 on the south western slopes of Banderpooch peaks in the miles), lies between the YamunotriGlacier (Uttarakhand) uppermost region of the lower Himalayas in the state of and Tajewala/Hathnikund Barrage (Haryana).