Reconciliation for Whom? Fostering Meaningful Relationships Through

Indigenous Tourism in Ontario

by

Jordan Daniels

A Thesis presented to

The University of Guelph

In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of

Master of Arts in

Public Issues Anthropology

Guelph, Ontario, Canada

© Jordan Daniels, August 2020

ABSTRACT

RECONCILIATION FOR WHOM? FOSTERING MEANINGFUL RELATIONSHIPS

THROUGH INDIGENOUS TOURISM IN ONTARIO

- Jordan Daniels

- Advisor:

- University of Guelph, 2020

- Dr. Thomas McIlwraith

The development of Indigenous tourism worldwide has attracted the attention of both travelers and scholars. However, current research regarding Indigenous Tourism in Canada fails to acknowledge how Indigenous tourism benefits the community in which it occurs while simultaneously fostering a meaningful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. To address this, I engage with the concept of reconciliation and explore tourism as a tangible way in which Canadians can engage with this often-abstract concept. This project is ethnographic in nature and involves a relational and collaborative approach with Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory located on the northeastern peninsula of Manitoulin Island, Ontario. My findings draw on semi-structured interviews with Wikwemikong Tourism employees and participant observation during a three week stay in the community during August 2019. Overall, this thesis demonstrates how the interactions that occur through Indigenous tourism create a dialogue of mutual understanding that is crucial for reconciliation in Canada. iii

DEDICATION

To all Canadians – Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike – committed to creating dialogue with one another, building relationships and taking active, meaningful steps towards reconciliation. iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory Chief and Council and the Wikwemikong Development Commission for recognizing the importance of this research, for approving this project and for welcoming me into your community.

Chi-Miigwetch to Luke Wassegijig and the employees at Wikwemikong Tourism for supporting my ideas, for making space for me in your organization, for participating in this research and most importantly, for your hard work making tourism in Wiikwemkoong thrive.

Chi-Miigwetch to Doris Peltier and Rita Corbiere and all those who I had the privilege of engaging with during my time in Wiikwemkoong: thank you for taking the time to share your ideas with me and for listening to mine.

Chi-Miigwetch to Priscilla Wassegijig, for sharing your home and your language with me, filling my belly with endless amounts of baked goods and for making Wiikwemkoong feel like home.

Many thanks to the Manitoulin Anishinaabek Research Review Committee for taking the time to review my proposal for this research; the thoughtful and critical comments provided by your reviewers ultimately shaped the form this project would take.

Thank you to my thesis advisor, Dr. Tad McIlwraith; throughout this entire process, your insightful comments and questions pushed me to think critically and encouraged me to always look for ways to improve my work. Your unwavering confidence in my abilities as a researcher and a writer provided me with the assurance I needed to see this project through. Thank you to my committee members Dr. Leah Levac and Dr. Brittany Luby, for taking the time to be involved in this project and for always providing me with a new perspective to consider. I am grateful to have had such intelligent and thoughtful mentors to guide me through this process and whose commitments to community-engaged and respectful scholarship will forever be an inspiration to me.

Thank you to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for providing me with the funding which made it possible to conduct this research in a meaningful and respectful way.

Finally, I am grateful for my family, friends and my boyfriend, Brett, for supporting me throughout this journey, despite not being entirely sure what I was working on half the time; as well as my dear friends and cohort members Liz and Jenna, who knew all too well what this process entailed. Thank you for joining me on endless trips to the library - productive or not, your encouragement and company was always much appreciated. v

Table of Contents

Abstract.................................................................................................................................ii Dedication............................................................................................................................iii Acknowledgements ...............................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................v List of Tables And Figures.................................................................................................. viii List of Appendices ................................................................................................................ix

Chapter One – Situating Indigenous Tourism on Odawa Mnis...............................................1

Introduction......................................................................................................................1

Summary of the Research ...................................................................................................................... 1 Research Development and Rationale ................................................................................................... 3

1.1.1 1.1.2

Literature Review.............................................................................................................4

Introduction............................................................................................................................................ 4 Conceptualizing Indigenous Tourism in Canada................................................................................... 4 Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Relations............................................................................................ 7 Conceptualizing Reconciliation ............................................................................................................. 9 Theoretical Considerations................................................................................................................... 11

1.2.1 1.2.2 1.2.3 1.2.4 1.2.5

Who are the Anishinabek of Odawa Mnis?.....................................................................14

History of Contact and Treaty Relationships....................................................................................... 16 Economic, Social and Political Organization....................................................................................... 20 Language and Spirituality .................................................................................................................... 22

1.3.1 1.3.2 1.3.3

Wikwemikong Tourism: A Case Study Approach ..........................................................23

- 1.4.1

- Structure of Wikwemikong Tourism ................................................................................................... 24

Overview of Chapters.....................................................................................................25

Chapter Two – Methodological Considerations ....................................................................28

Introduction....................................................................................................................28 The Colonial Roots of Research......................................................................................28 Finding the Way Forward ..............................................................................................31

Influence of Indigenous Scholars and Ways of Knowing.................................................................... 32 The Importance of Un-learning and Reflexivity.................................................................................. 33 Situating Myself Within the Research ................................................................................................. 34 Ethical and Respectful Engagement..................................................................................................... 36

2.3.1 2.3.2 2.3.3 2.3.4

Data Collection ...............................................................................................................37

Semi-Structured Interviews.................................................................................................................. 38 Participant Observation........................................................................................................................ 39 A Day in the Life.................................................................................................................................. 40

2.4.1 2.4.2 2.4.3

Data Analysis..................................................................................................................42 Reflection on the Research Process.................................................................................42

vi

Chapter Three – Exploring Wiikwemkoong Through “Authentic Indigenous Experiences”..44

Introduction....................................................................................................................44

“Experience Wiikwemkoong”.........................................................................................44

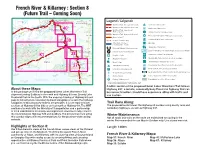

My Experience as a Tourist.................................................................................................................. 45 Annual Cultural Festival ...................................................................................................................... 46 Lakeshore Tour and the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation.......................................................................... 48 Killarney Provincial Park..................................................................................................................... 49 Point Grondine Park............................................................................................................................. 50 The Unceded Journey........................................................................................................................... 51 Great Canadian Tour............................................................................................................................ 52 Bebamikawe ‘Making Footprints’ ....................................................................................................... 54

3.2.1 3.2.2 3.2.3 3.2.4 3.2.5 3.2.6 3.2.7 3.2.8

The “Image” of Wikwemikong Tourism.........................................................................54

- 3.3.1

- The Importance of Authenticity and Integrity ..................................................................................... 55

Understanding the Guests...............................................................................................57

Tourist Expectations............................................................................................................................. 58 The Uninformed and Inappropriate...................................................................................................... 60 The Informed and Open-minded.......................................................................................................... 61

3.4.1 3.4.2 3.4.3

Limits in the Sharing Process..........................................................................................62 Discussion and Conclusion..............................................................................................65

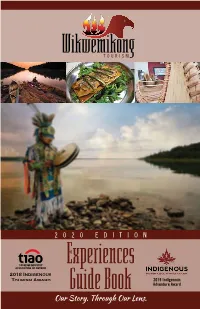

Chapter Four – “Our Story. Through Our Lens”: Disrupting, Sharing and Reclaiming

Through Tourism................................................................................................................69

Introduction....................................................................................................................69 Disrupting the Colonial Narrative ..................................................................................69 Reflecting on the Past: Historical Injustices....................................................................71 Presenting a New Narrative............................................................................................73 Discussion and Conclusion..............................................................................................75

Chapter Five – Creating Impacts and Building Relationships Through the Tourism

Experience ..........................................................................................................................78

Introduction....................................................................................................................78 Impacts on Tourists ........................................................................................................78 Impacts on Tourism Employees......................................................................................81 Impacts on the Community At Large..............................................................................84

Informal Interactions: Implications for Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Relationships .87

Reconciliation and Indigenous Tourism..........................................................................91

What is Reconciliation? ....................................................................................................................... 91 Reconciliation and Wikwemikong Tourism ........................................................................................ 96

5.6.1 5.6.2

Discussion and Conclusion..............................................................................................98

Chapter Six – Concluding Remarks, Reflections and Recommendations.............................101

vii

Summary of Arguments................................................................................................101 Contributions................................................................................................................102 Benefits to Wiikwemkoong ...........................................................................................103 Recommendations for Wikwemikong Tourism.............................................................104 Knowledge Mobilization ...............................................................................................106 Limitations and Future Research .................................................................................106 Continuing the Relationship .........................................................................................107