Background Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fostering Meaningful Relationships Through Indigenous Tourism in Ontario

Reconciliation for Whom? Fostering Meaningful Relationships Through Indigenous Tourism in Ontario by Jordan Daniels A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Daniels, August 2020 ABSTRACT RECONCILIATION FOR WHOM? FOSTERING MEANINGFUL RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS TOURISM IN ONTARIO Jordan Daniels Advisor: University of Guelph, 2020 Dr. Thomas McIlwraith The development of Indigenous tourism worldwide has attracted the attention of both travelers and scholars. However, current research regarding Indigenous Tourism in Canada fails to acknowledge how Indigenous tourism benefits the community in which it occurs while simultaneously fostering a meaningful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. To address this, I engage with the concept of reconciliation and explore tourism as a tangible way in which Canadians can engage with this often-abstract concept. This project is ethnographic in nature and involves a relational and collaborative approach with Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory located on the northeastern peninsula of Manitoulin Island, Ontario. My findings draw on semi-structured interviews with Wikwemikong Tourism employees and participant observation during a three week stay in the community during August 2019. Overall, this thesis demonstrates how the interactions that occur through Indigenous tourism create a dialogue of mutual understanding that is crucial for reconciliation in Canada. iii DEDICATION To all Canadians – Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike – committed to creating dialogue with one another, building relationships and taking active, meaningful steps towards reconciliation. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory Chief and Council and the Wikwemikong Development Commission for recognizing the importance of this research, for approving this project and for welcoming me into your community. -

Transfer of Crown Land to Contribute to the Settlement of the Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim Environmental Study Report

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT – WIIKWEMKOONG ISLANDS BOUNDARY CLAIM – PROPOSED LAND TRANSFER AUGUST 2019 Transfer of Crown Land to Contribute to the Settlement of the Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim Environmental Study Report A Project under the Class Environmental Assessments for Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) Resource Stewardship and Facility Developments Projects (RSFD) and Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves (PPCR) Ministry of Indigenous Affairs August 2019 This Final Environmental Study Report has been prepared as a Project Plan Report for the Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim – Proposed Land Transfer as a part of the Category C Project Evaluation and Consultation Process as outlined in Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Class Environmental Assessment for Resource Stewardship and Facility Development Projects and the Class Environmental Assessment for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves. FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT – WIIKWEMKOONG ISLANDS BOUNDARY CLAIM – PROPOSED LAND TRANSFER AUGUST 2019 Cette publication hautement spécialisée Environmental Study Report n'est disponible qu'en anglais conformément au Règlement 671/92, selon lequel il n’est pas obligatoire de la traduire en vertu de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir des renseignements en français, veuillez communiquer avec le ministère des Affaires autochtones au 1-866-381-5337 ou [email protected]. 2 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT – WIIKWEMKOONG ISLANDS -

Multi- Day Manitoulin-Killarney Itinerary

Our story. Through our lens. Multi-day itinerary – Manitoulin Island-Killarney Motor Coach Tours Manitoulin Island -Killarney itineraries include a combination of indigenous culture, nature hikes, sightseeing with fabulous accommodations and cuisine. Connect to the mainland with a Georgian Bay sightseeing cruise to Killarney and stay at the luxurious Killarney Mountain Lodge and Canada House Conference Center. This circle route itinerary is perfect for groups originating from Southern Ontario destinations. Our motor coach and group packages are fully customizable. Sample Itinerary Day One Itinerary: 9:00am Depart hotel to Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory 9:45am Arrive 1836 historic site: Met by Wikwemikong Tourism step-on guides 9:45am-11:45am The Unceded Journey guided tour: learn the history of Odawa Mnis (Manitoulin Island) and Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory—Canada’s only officially recognized Unceded Indian Reserve. Includes stops at four historic sites including 1836 Treaty historic site, Holy Cross Mission Ruins (residential school site), Smith Bay trading site. 11:50am-1:00pm Catered lunch: Authentic Indigenous Cuisine 1:10pm-3:30pm Indigenous Culinary Experience at Outdoor Culinary Space 4:00pm-4:45pm Depart to hotel 5:00pm-6:00pm Dinner 6:00pm – 9:00pm Dewegan-Drum & Song Interactive Community Social at hotel Includes MC, full drum group, dance demonstrations (dancers in full regalia), and catered appetizers Day Two Itinerary: 8:45am Wikwemikong Tourism step-on guides arrive at hotel 9:00am-9:30am Depart hotel. Travel to M’Chigeeng First Nation 9:30am-10:10am Lillian’s Crafts: gift shop & museum 10:15am-11:45am Ojibwe Cultural Foundation guided tour: Healing Lodge, Museum, Residential School Exhibit, and Gift shop- 12:00pm-1:00pm Catered Lunch: Authentic Indigenous Cuisine 1:00pm-1:20pm Depart to Kagawong, ON 1:20pm-3:20pm Bridal Veil Falls and walk nature trail Kagawong History: Old Mill Heritage Centre, Kagawong Lighthouse, St. -

Renewable Energy Applications on Provincial Crown Land Demande

97°0'0"W 96°0'0"W 95°0'0"W 94°0'0"W 93°0'0"W 92°0'0"W 91°0'0"W 90°0'0"W 89°0'0"W 88°0'0"W 87°0'0"W 86°0'0"W 85°0'0"W 84°0'0"W 83°0'0"W 82°0'0"W 81°0'0"W 80°0'0"W 79°0'0"W 78°0'0"W 77°0'0"W 76°0'0"W 75°0'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°0'0"W 56°0'0"N 56°0'0"N Hudson Bay (baie d' Hudson) FORT SEVERN 89 55°0'0"N 55°0'0"N R rn ve Se isk R Win Echoing Lake Stull POLAR BEAR Lake W i n 54°0'0"N is k IKÝ R 54°0'0"N Pierce Lake Little Sachigo Lake WINISK 90 R ig IKÝ we SACHIGO he SEVERN s LAKE 2 RIVER A Severn Renewable Energy Applications C Lake len de SACHIGO nn LAKE 1 ing R SACHIGO Sachigo LAKE 3 Lake KITCHENUHMAYKOOSIB on Provincial Crown Land BEARSKIN Opinnagau LAKE AAKI 84 FAWN WAPEKEKA Lake RIVER RESERVE 2 Ck isi gg IKÝ Me OPASQUIA Big Trout WAPEKEKA IKÝ Lake RESERVE 1 KASABONIKA LAKE Shibogama R Lake n Muskrat ia ks Dam Lake n yCk Ba rd ea James Bay B eig R Demande relatives à l'énergie renouvelable Ash ew ATTAWAPISKAT 91 MUSKRAT Makoop 53°0'0"N DAM LAKE (baie James) !(WA-4 Lake WAWAKAPEWIN Gorm Sta an i R n B 53°0'0"N a R y S ly R e v R sur les terres provinciales de la Couronne Finger Lake e r n SANDY LAKE 88 Sandy Lake WINISK KEEWAYWIN R RIVER x o Magiss F Lake IKÝ KINGFISHER WEAGAMOW LAKE 1 Wunnummin LAKE 87 KINGFISHER 3A Lake Winisk Lake Nikip Weagamow Wapikopa Lake R Lake Lake KINGFISHER 2A Kanuchuan io r Chipai At d Lake tawa o piskat R n Lake DEER C WEBEQUIE ATTAWAPISKAT LAKE k North 91A 5040 30 20 10 0 50 100 150 Caribou WUNNUMIN 1 Nibinamik Deer Lake Lake k Lake tt C WUNNUMIN 2 G cke North Bu L af R Spirit fer is Kilometres/kilomètres -

L a K E M I C H I G a N Lake Ontario Lake Erie Lake Superior Lake Huron

Xeneca FIT Site Selection Map 95°0'0"W 94°0'0"W 93°0'0"W 92°0'0"W 91°0'0"W 90°0'0"W 89°0'0"W 88°0'0"W 87°0'0"W 86°0'0"W 85°0'0"W 84°0'0"W 83°0'0"W 82°0'0"W 81°0'0"W 80°0'0"W 79°0'0"W 78°0'0"W 77°0'0"W 76°0'0"W 75°0'0"W Project Rivers and Tributaries Mnr Site MNR District Latitude Longitude Ivanhoe River The Chute Ivanhoe 4LC18 Chapleau N48° 23' 28" W82° 27' 7" N N " " 0 0 ' Ivanhoe River Third Falls Ivanhoe 4LC17 Chapleau N48° 36' 21" W82° 21' 29" ' 0 0 ° ° 7 Wanatango Falls Fredickhouse 4MD02 Cochrane N48° 51' 12" W81° 4' 12" 7 5 5 Island Falls Seine 5PB05 Fort Frances N48° 49' 06" W91° 18' 54" Long Rapids Seine 5PB04 Fort Frances N48° 56' 51" W91° 7' 48" Outlet Kapuskasing Lake Kapuskasing 4LE01 Chapleau N48° 34' 6" W82° 51' 43" Lapinigam Rapids Kapuskasing 4LE03 Hearst N48° 43' 0" W82° 50' 0" Middle Twp Buchan Kapuskasing 4LE05 Hearst N48° 46' 14" W82° 50' 54" Near North Boundary Kapuskasing 2LF9 Hearst N48° 50' 18" W82° 50' 17" N Jocko River Jocko 2JE16 North Bay N46° 33' 48" W79° 0' 18" N " " 0 0 ' Big Eddy Petawawa Green Electricity Development Inc. Petawawa 2KB21 (CPR Bridge) Pembroke N45° 53' 59" W77° 17' 24" ' 0 0 ° ° 6 6 5 Half Mile Green Electricity Development Inc. -

Ontario / Terres Du Canada

98° 97° 96° 95° 94° 93° 92° 91° 90° 89° 88° 87° 86° 85° 84° 83° 82° 81° 80° 79° 78° 77° 76° 75° 74° 73° 72° 71° CANADA LANDS - ONTARIO TERRES DU CANADA - ONTARIO 56° er iv And Other Lands Managed Under the Et autres terres gérées sous le Système R k c Canada Lands Survey System d'arpentage des terres du Canada u D 56° ck la B Hudson Bay Scale / Échelle 1:2000000 0 25 50 100 150 200 Baie d'Hudson kilom e tre s kilom ètre s r ive i R ib 1 ce ntim e tre re pre se nts 20 kilom e tre s / 1 ce ntim ètre re prése nte 20 kilom ètre s sk Ni La m be rt Conform a l Conic Proje ction, sta nd a rd pa ra lle ls 49º N a nd 77º N. Proje ction La m be rt conique conform e , pa ra llèle s sta nd a rd s 49º N e t 77º N. Fort Severn 89 MA ! NITOBA Prod uce d by the Surve yor Ge ne ra l Bra nch (SGB), Prod uit pa r la Dire ction d e l’a rpe nte ur g énéra l (DAG), Na tura l R e source s Ca na d a . R e ssource s na ture lle s Ca na d a . 55° B e av er This m a p is not to be use d for d e fining bound a rie s. It is m a inly a n ind e x Ce tte ca rte ne d oit pa s ê tre utilisée pour d éte rm ine r le s lim ite s. -

Wiikwemkoong Islands Transfer

CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT WIIKWEMKOONG ISLANDS RESERVE BOUNDARY CLAIM – PROPOSED LAND TRANSFER MINISTRY OF INDIGENOUS RELATIONS AND RECONCILIATION June 2017 This Draft Environmental Study Report has been prepared as a Project Plan Report for the Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim – Proposed Land Transfer as a part of the Category C Project Evaluation and Consultation Process as outlined in Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Class Environmental Assessment for Forestry Resource Stewardship and Facility Development Projects. DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT - WIIKWEMKOONG ISLANDS BOUNDARY CLAIM – PROPOSED LAND TRANSFER – JUNE 12, 2017 Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 2 2.0 PROJECT PROPOSAL .................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Project Description .................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Description of Study Area ......................................................................................... 3 Table 1: Species at Risk - Manitoulin ....................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Table 2: Location Reference Table (Toma Kinoshameg Fishing Boundary Area) ................... 6 Table 3: Location Reference Table (Heywood Island) ............................................................ 6 Table 4: Species at Risk - Sudbury ......................................... -

Experiences Guide Book Our Story

WikwemikongTOURISM 2019 EDITION Experiences Guide Book Our Story. Through Our Lens. Message From Ogimaa Duke Peltier WIIKWEMKOONG UNCEDED TERRITORY The Anishinaabek people of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory have lived on Manitoulin Island since time immemorial. The village of Wiikwemkoong is on the eastern portion of the island and along the beautiful and pristine shores of Georgian Bay. Our vibrant community expresses its Anishinaabek culture through several events that draw visitors from all over the world. Some of those events include the annual cultural festival, fall fair, ice fishing derby, traditional pow-wow, and aboriginal theatre in the ruins of a historic Church. I invite you all to visit Wiikwemkoong and also our beautiful Point Grondine Park which is situated near Killarney, Ontario. Enjoy the wilderness through one of our many private and community operated tourism services. Our land base provides plenty of opportunities for both a wilderness experience and to enjoy the culture of our people. Point Grondine Park is operated as a recreational park and has over 7000 hectares of scenic natural wilderness landscape, old growth pine forest, stunning river vistas and eight interior lakes to explore. The picturesque water trails flowing along the coast of Georgian Bay invite you to many canoe routes, hiking trails and backcountry campsites located throughout the interior of the Park. Hike, canoe or sea kayak along the traditional routes of the Anishinaabek people and be ready to be captivated by this historic and majestic place. We are conveniently accessible by road and by boat. Our Tourism Information Center is centrally located and provides travelers with in-depth information pertaining to Manitoulin Island. -

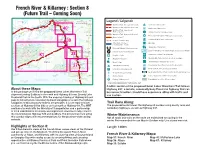

Collingwood to Sudbury Web Maps.Indd

French River & Killarney : Section 8 (Future Trail – Coming Soon) VermilionVermilion 31 144 LLakeake LakeLake ScienceScienScieccienceienceiencencncce NorthNoN oorrtrthth 55 ConistonConistoConistononn Callumum FFairbankairbank SciScienceScieSciencienccienceiencei ncncee NoNNordordordrd CopperCo r SudburySudbuSudbudburybururyuurryy 67 O LLakeake WWahnapitaeahnapitaet 999 VR 535 FairbankFairbankir k LakeLakLakekeeLauree Laurentian LaurenLaurentLaLauLLaureLaurentia rentree tiianiiaan k Markstayar Legend / Légende CliffCliff 55 37 eek 24 46 r Livelyveelylyy 17 DaisyDDaaisyaaiisyisisysy LakeLLa Lakakee CreekC Markstay-Markstay-WarrenWarrenrenen 5 21 UplandsUplUplandplaplanllanlandlaandsandsds 122 CPC HagarH 8 Waterfront Trail - On-road / Sur la route Town Hall / Hôtel de ville 69 CN 4 RedRe Deer 15 MikkolaMMik 8080 MMcFaMcMcFarlaneFarlaneFarFlFa 13 537537 Lake 55 LakeLa 69 LakeLa Waterfront Trail - Off-road / Hors route Fallsallss WorthingtonWorthingtonortor hingtong 4 3 NaughtonNaugNaugghththtot RRheaultRheauRheaulaultult Washrooms / Washrooms kkee 4 GreaterGGrea Sudbury/Sudbury/y 4019 r TurbineTurbine WhitefishWhitWhiteefishh LongLLon WWanupanupp 535535 Waterfront Trail - Gravel road / RiverR WhitefishW itte Grand SudburySudbury assi NNaairnirn LakeL kee LakeL w w River o e St.. CharlesC Route en gravier Railway Crossing / Passage à niveau entreentntre 17 ElbowElb NepNepewassi n BeaverBeaveB Roundd CCaas 38 Vermiliomimilio LLakeake Waterfront Trail - Proposed / Proposée LakeL SecordSecord StSt.. - CharleCCharlh e Roofed Accommodation / Hébergement -

Land Information Ontario Data Description

Unclassified Land Information Ontario Data Description ORN Segment with Address Disclaimer This technical documentation has been prepared by the Ministry of Natural Resources (the “Ministry”), representing Her Majesty the Queen in right of Ontario. Although every effort has been made to verify the information, this document is presented as is, and the Ministry makes no guarantees, representations or warranties with respect to the information contained within this document, either express or implied, arising by law or otherwise, including but not limited to, effectiveness, completeness, accuracy, or fitness for purpose. The Ministry is not liable or responsible for any loss or harm of any kind arising from use of this information. For an accessible version of this document, please contact Land Information Ontario at (705) 755 1878 or [email protected] ©Queens Printer for Ontario, 2019 LIO Class Description ORN Segment with Address Class Short Name: ORNSEGAD Version Number: 3 Class Description: A geospatial database of the Ontario road network and its associated attributes, e.g. its street name or road number, its address information, road classification, etc. The segmented version of the ORN is derived from the ORN Linear Reference System (LRS) format and is suitable for routing and context mapping. The segmented version of the ORN does not differentiate between road elements and ferry connections. They are combined into a feature called road segment. The segmented version of the ORN is comprised of distinct segments, usually from intersection to intersection, and contains only five attributes: Street Name Address Information Route Identification Road Classification Direction of Traffic Flow Abstract Class Name: SPSLINE Abstract Class Description: Spatial Single-Line: An object is represented by ONE and ONLY ONE line segment. -

Experiences Guide Book

WikwemikongTOURISM 2020 EDITION Experiences 2019 Indigenous Guide Book Adventure Award Our Story. Through Our Lens. Message From Ogimaa Duke Peltier WIIKWEMKOONG UNCEDED TERRITORY The Anishinaabek people of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory have lived on Manitoulin Island since time immemorial. The village of Wiikwemkoong is on the eastern portion of the island and along the beautiful and pristine shores of Georgian Bay. Our vibrant community expresses its Anishinaabek culture through several events that draw visitors from all over the world. Some of those events include the annual cultural festival, fall fair, ice fishing derby, traditional pow-wow, and aboriginal theatre in the ruins of a historic Church. I invite you all to visit Wiikwemkoong and also our beautiful Point Grondine Park which is situated near Killarney, Ontario. Enjoy the wilderness through one of our many private and community operated tourism services. Our land base provides plenty of opportunities for both a wilderness experience and to enjoy the culture of our people. Point Grondine Park is operated as a recreational park and has over 7000 hectares of scenic natural wilderness landscape, old growth pine forest, stunning river vistas and eight interior lakes to explore. The picturesque water trails flowing along the coast of Georgian Bay invite you to many canoe routes, hiking trails and backcountry campsites located throughout the interior of the Park. Hike, canoe or sea kayak along the traditional routes of the Anishinaabek people and be ready to be captivated by this historic and majestic place. We are conveniently accessible by road and by boat. Our Tourism Information Center is centrally located and provides travelers with in-depth information pertaining to Manitoulin Island.