Kant and the Problem of Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Imagination Bound: a Theoretical Imperative

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Philosophy Philosophy 2016 Imagination Bound: A Theoretical Imperative Robert Michael Guerin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.017 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Guerin, Robert Michael, "Imagination Bound: A Theoretical Imperative" (2016). Theses and Dissertations-- Philosophy. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/philosophy_etds/8 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Philosophy by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

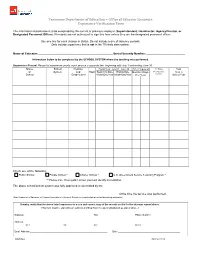

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Episteme IS FOUNDATIONAL a PRIORI JUSTIFICATION INDISPENSABLE?

Episteme http://journals.cambridge.org/EPI Additional services for Episteme: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here IS FOUNDATIONAL A PRIORI JUSTIFICATION INDISPENSABLE? Ted Poston Episteme / Volume 10 / Issue 03 / September 2013, pp 317 - 331 DOI: 10.1017/epi.2013.25, Published online: 07 August 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1742360013000257 How to cite this article: Ted Poston (2013). IS FOUNDATIONAL A PRIORI JUSTIFICATION INDISPENSABLE?. Episteme, 10, pp 317-331 doi:10.1017/epi.2013.25 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/EPI, IP address: 108.195.178.103 on 23 Aug 2013 Episteme, 10, 3 (2013) 317–331 © Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/epi.2013.25 is foundational a priori justification indispensable? ted poston1 [email protected] abstract Laurence BonJour’s (1985) coherence theory of empirical knowledge relies heavily on a traditional foundationalist theory of a priori knowledge. He argues that a foundationalist, rationalist theory of a priori justication is indispensable for a coherence theory. BonJour (1998) continues this theme, arguing that a traditional account of a priori justication is indispensable for the justication of putative a priori truths, the justication of any non-observational belief and the justication of reasoning itself. While BonJour’s indispensability arguments have received some critical discussion (Gendler 2001; Harman 2001; Beebe 2008), no one has inves- tigated the indispensability arguments from a coherentist perspective. This perspec- tive offers a fruitful take on BonJour’s arguments, because he does not appreciate the depth of the coherentist alternative to the traditional empiricist-rationalist debate. -

![272 Bibliography Abbreviations for Frequently Cited Works Analysis = Mill [1829] E&W = Bain [1859] EAP = Reid[1788/1969]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4182/272-bibliography-abbreviations-for-frequently-cited-works-analysis-mill-1829-e-w-bain-1859-eap-reid-1788-1969-704182.webp)

272 Bibliography Abbreviations for Frequently Cited Works Analysis = Mill [1829] E&W = Bain [1859] EAP = Reid[1788/1969]

Bibliography Abbreviations for Frequently Cited Works Analysis = Mill [1829] E&W = Bain [1859] EAP = Reid[1788/1969] EIP = Reid [1785/1969] First Enquiry = “An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding” in Hume [1777/1975] Inquiry = Reid [1764/1997] Lectures = Brown [1828/1860] or Hamilton [1844/1877] (sense obvious in context) Observations, OM = Hartley [1749/1966] S&I = Bain [1855] Sketch = Brown [1820/1977] SSR = Kuhn [1962/1970] Treatise = Hume [1739-1740/1978] Section I: Primary Sources Allen, Grant, Physiological Aesthetics [Garland Publishing, 1877]. Bain, Alexander, The Senses and the Intellect [University Publications of America, 1855/1977]. Bain, Alexander, The Emotions and the Will [University Publications of America, 1859/1977]. Bain, Alexander, “The Early Life of James Mill” in Mind, 1(1), pp.97-116 [1876a]. Bain, Alexander, “The Life of James Mill” in Mind, 1(4), pp.509-531 [1876b]. Bain, Alexander, James Mill: A Biography [Augustus M. Kelley, 1882a/1967]. Bain, Alexander, John Stuart Mill: A Criticism with Personal Reflections [Longmans, Green and Co., 1882b]. Bain, Alexander, Autobiography [1904]. Barzellotti, Giacomo, “Philosophy in Italy” in Mind, 3(12), pp.505-538 [1878]. Berkeley, George, A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, Jonathan Dancy, ed. [Oxford University Press, 1710/1998] Brown, Thomas, Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind [Hallowell Glazer and Co., 1828]. 272 Brown, Thomas, Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind [William Tegg, 1828/1860 (20th Edition)]. Brown, Thomas, Sketch of a System of the Philosophy of the Human Mind [1820], reprinted in Significant Contributions to the History of Psychology, Series A: Orientations, Volume I, Daniel N. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Coherence, Truth, and the Development of Scientific Knowledge*

Coherence, Truth, and the Development of Scientific Knowledge* Paul Thagard†‡ What is the relation between coherence and truth? This paper rejects numerous answers to this question, including the following: truth is coherence; coherence is irrelevant to truth; coherence always leads to truth; coherence leads to probability, which leads to truth. I will argue that coherence of the right kind leads to at least approximate truth. The right kind is explanatory coherence, where explanation consists in describing mech- anisms. We can judge that a scientific theory is progressively approximating the truth if it is increasing its explanatory coherence in two key respects: broadening by explaining more phenomena and deepening by investigating layers of mechanisms. I sketch an explanation of why deepening is a good epistemic strategy and discuss the prospect of deepening knowledge in the social sciences and everyday life. 1. Introduction. The problem of the relation between coherence and truth is important for philosophy of science and for epistemology in general. Many epistemologists maintain that epistemic claims are justified, not by a priori or empirical foundations, but by assessing whether they are part of the most coherent account (see, e.g., Bonjour 1985; Harman 1986; Lehrer 1990). A major issue for coherentist epistemology concerns whether we are ever warranted in concluding that the most coherent account is true. In the philosophy of science, the problem of coherence and truth is part of the ongoing controversy about scientific realism, the view that science aims at and to some extent succeeds in achieving true theories. The history of science is replete with highly coherent theories that have turned out to be false, which may suggest that coherence with empirical evidence is a poor guide to truth. -

Freewill and Determinism: the African Perspective and Experience

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.2, pp.75-82, February 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) FREEWILL AND DETERMINISM: THE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE AND EXPERIENCE Augustine Chidi Igbokwe, Department of Philosophy, Caritas University, Amorji – Nike P.M.B 01784, Enugu Enugu State – Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Whether Freewill and/or determinism has been an age long heated debate in the history of Western philosophy. The African metaphysical enquiry attempts a resolution by establishing a complementarity parlance between the two. Reality then becomes a paradox of harmony of opposites. In the midst of this harmony, a realization comes that the more a society turns modern, the more freedom is identified, subjecting deterministic tendencies to the periphery. As Africa is on the process to modernity, the system of communalism that had hitherto served Africa now gives way to individualism. In the same vein, there is need for a conscious change from unorganized but effective brotherhood to corporate and efficient governance to synergize this paradigm shift KEYWORDS: Freewill; Determinism; Communalism; Individualism; Free-Determinism. INTRODUCTION The philosophical argument on freewill and determinism which dates back to the ancient period still takes the front burner in our philosophical discourse today. How free are our actions and the choices we make? This question becomes pertinent when we juxtapose it with the long assumed assertion that every effect has a cause. If our actions as effects are all caused, then how morally responsible are we in our actions? This is usually the major paradox in the discourse on freewill and determinism and this is the major rationale behind the insistence on the heated debate. -

Three Kinds of Coherentism

THREE KINDS OF COHERENTISM Jaap Hage* [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to show what makes coherentism attractive in comparison to its main competitor, foundationalism. It also aims to show that constraint satisfaction is not the most attractive way to give content to the notion of coherence. In order to achieve these purposes, the paper distinguishes between epistemic, constructive and integrated coherentism. Epistemic coherentism treats coherence as a test for knowledge about a world which exists independently (ontological realism). Constructive coherentism uses coherence as a standard to determine what the facts are in a particular domain. This is a form of ontological idealism. Usually, both epistemic and constructive coherentism apply the coherence test to only part of the positions (beliefs etc.) which a person accepts. The definition of and standards for coherence, just as usually logic and standards for belief revision are kept outside the process of making a position set coherent. Integrated coherentism differs by including everything in the coherence creating process. A set of positions is integratedly coherent if and only if it satisfies the standards included in the set of positions itself. The paper argues that integrated coherentism best fits with the ideas underlying coherentism and that it is incompatible with coherence as constraint satisfaction in a strict sense. Keywords: integrated coherence, epistemic coherence, constructive coherence, defeasible coherence, narrow coherence, negative coherence, foundationalism, constraint satisfaction, meta-belief, pseudo-realism, truth connection, reflective equilibrium, position, justification, truth. 1 INTRODUCTION Coherentism has its basis in epistemology (Bonjour 1985; Lehrer 1992 and 2000; Thagard and Verbeurgt 1998; Thagard 2000; Kvanvig 2011) and ramifications into ontology (Rescher 1973; Young 2008), but has also become popular in ethical theory (Rawls 1972; Daniels 2011) and in jurisprudence (MacCormick 1978 and 2005; Dworkin 1978 and 1986; Peczenik 2008; Amaya 2007). -

128 Dale E. Miller the Great Virtue of This Book Is That It Takes Seriously Mill's Utilitarianism. Too Many Accounts of Mill B

128 book reviews Dale E. Miller J.S. Mill: Moral, Social and Political Thought, (Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity), 252 pp. ISBN: 978-0-07456-2583-6 (hbk); 978-0-7456-2584-3 (pbk). Hardback/ Paperback: £ 55.00/15.99. The great virtue of this book is that it takes seriously Mill’s utilitarianism. Too many accounts of Mill’s thought have attempted to reinterpret Mill as anything but a utilitarian. This fashion was perhaps established by Isaiah Berlin’s account of Mill in ‘John Stuart Mill and the Ends of Life’, where Mill’s commit- ment to individual liberty is seen in terms of a retreat from the utilitarianism of Bentham and his father James Mill. Many studies of Mill take the view that, while his liberalism is to be applauded, his utilitarianism is to be regretted, and is, therefore, best written out of the account as something of an embarrass- ment. All this, presumably, is a result of the current obsession with intuition- ism and so-called deontological ethics (I say so-called since it was Bentham who invented the term ‘deontology’). Miller emphasizes the fact that Mill was never anything but a utilitarian throughout his career. He might have added that liberalism itself is a product of utilitarianism, and that this is something that contemporary liberals would do well to remember. Miller presents a philosophical reconstruction of Mill’s thought. He occa- sionally gives some historical context, for instance where Mill’s views might otherwise appear puzzling to the contemporary reader, but his main focus is on providing the best systematic account of Mill’s corpus, and on showing how it remains relevant to today’s debates and concerns, both theoretical and prac- tical. -

Hume's Central Principles

Hume’s Central Principles 2. Overview, Hume’s Theory of Ideas, and his Faculty Psychology Peter Millican Hertford College, Oxford An Integrated Vision ! We have seen how Hume’s investigation of the notion of causation brought together his interest in the Cosmological Argument for God’s existence, free will and the Problem of Evil, his opposition to aprioristic metaphysics (e.g. concerning mind and matter), and his view of human beings as part of the natural world, amenable to empirical investigation. ! Although there is historical evidence of his early interest in these things, they come together most clearly not in the Treatise itself (January 1739), but in the Abstract (autumn 1739) and the Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (1748) … 2 The Topics of the Abstract Introduction Associationism Probability Liberty and Necessity Copy Principle Sceptical Résumé Induction Idea of Necessity Belief Probability Personal Identity Passions 3 Geometry Overview (1) ! Starts from a theory of mental contents: impressions (sensations or feelings) and ideas (thoughts). ! Empiricist: all ideas are derived from impressions (and hence from experience) – Hume’s Copy Principle. ! Assumes a theory of faculties (reason, the senses, imagination etc.), in terms of which he expresses many of his main results. 4 Overview (2) ! Aims to deny that we have rational insight into things (and also – in his moral theory - that we are governed by reason). ! Relations of ideas / matters of fact –"roughly analytic / synthetic (but in the Treatise based on a theory of different kinds of relation) ! Demonstrative / probable reasoning –"roughly deductive / inductive 5 Overview (3) ! Induction presupposes an assumption of uniformity over time, which cannot be founded on any form of rational evidence.