Arxiv:1504.01453V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 7 Apr 2015 Ences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Search for Living Worlds and the Connection to Our Cosmic Origins

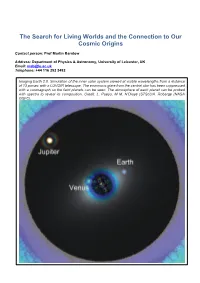

The Search for Living Worlds and the Connection to Our Cosmic Origins Contact person: Prof Martin Barstow Address: Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK Email: [email protected] Telephone: +44 116 252 3492 Imaging Earth 2.0. Simulation of the inner solar system viewed at visible wavelengths from a distance of 13 parsec with a LUVOIR telescope. The enormous glare from the central star has been suppressed with a coronagraph so the faint planets can be seen. The atmosphere of each planet can be probed with spectra to reveal its composition. Credit: L. Pueyo, M M. N’Diaye (STScI)/A. Roberge (NASA GSFC). The Search for Living Worlds – ESA Voyage 2050 White Paper Executive summary One of the most exciting scientific challenges is to detect Earth-like planets in the habitable zones of other stars in the galaxy and search for evidence of life. During the past 20 years the detection of exoplanets, orbiting stars beyond our own has moved from science fiction to science fact. From the first handful of gas giants, found through radial velocity studies, detection techniques have increased in sensitivity, finding smaller planets and diverse multi-planet systems. Through enhanced ground-based spectroscopic observations, transit detection techniques and the enormous productivity of the Kepler space mission, the number of confirmed planets has increased to more than 2000. There are several space missions, such as TESS (NASA), now operational, and PLATO (ESA), which will extend the parameter space for exoplanet discovery towards the regime of rocky earth- like planets and take the census of such bodies in the neighbourhood of the Solar System. -

CURRENT AFFAIRS= 18-12-2019 International Migrants Day

CURRENT AFFAIRS= 18-12-2019 International Migrants Day International Migrants Day is celebrated on 18 December to raise awareness about the protection for migrants and refugees. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) is calling an international community to come together and remember the migrants and refugees who have lost their lives or have disappeared while reaching a safe harbor. Government promises broadband access in all villages by 2022; launches National Broadband Mission. The government promised broadband access in all villages by 2022, as it launched the ambitious National Broadband Mission entailing stakeholder investment of Rs 7 lakh crore in the coming years. The mission will facilitate universal and equitable access to broadband services across the country, especially in rural and remote areas. It also involves laying of incremental 30 lakh route km of Optical Fiber Cable and increase in tower density from 0.42 to 1 tower per thousand of population by 2024. The mission unveiled by Communications Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad will also aim at significantly improving quality of services for mobile and internet. “By 2022, we will take broadband to all the villages of India.The number of towers in the country which is about 5.65 lakh will be increased to 10 lakh,” Prasad stated. The mission also envisages increasing fiberisation of towers to 70 per cent from 30 per cent at present. GEM launches National Outreach Programme – GEM Samvaad. A national outreach Programme, GeM Samvaad, was launched by Anup Wadhawan, Secretary, Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Go1vernment of India and Chairman, GeM in New Delhi. -

Jrasc-August'99 Text

Publications and Products of August/août 1999 Volume/volume 93 Number/numero 4 [678] The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Observer’s Calendar — 2000 This calendar was created by members of the RASC. All photographs were taken by amateur astronomers using ordinary camera lenses and small telescopes and represent a wide spectrum of objects. An informative caption accompanies every photograph. This year all of the photos are in full colour. The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Le Journal de la Société royale d’astronomie du Canada It is designed with the observer in mind and contains comprehensive astronomical data such as daily Moon rise and set times, significant lunar and planetary conjunctions, eclipses, and meteor showers. The 1999 edition received two awards from the Ontario Printing and Imaging Association, Best Calendar and the Award of Excellence. (designed and produced by Rajiv Gupta). Price: $13.95 (members); $15.95 (non-members) (includes taxes, postage and handling) The Beginner’s Observing Guide This guide is for anyone with little or no experience in observing the night sky. Large, easy to read star maps are provided to acquaint the reader with the constellations and bright stars. Basic information on observing the moon, planets and eclipses through the year 2005 is provided. There is also a special section to help Scouts, Cubs, Guides and Brownies achieve their respective astronomy badges. Written by Leo Enright (160 pages of information in a soft-cover book with otabinding which allows the book to lie flat). Price: $15 (includes taxes, postage and handling) Looking Up: A History of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Published to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the first meeting of the Toronto Astronomical Club, “Looking Up — A History of the RASC” is an excellent overall history of Canada’s national astronomy organization. -

2391 (Created: Tuesday, September 21, 2021 at 5:00:39 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview

JWST Proposal 2391 (Created: Tuesday, September 21, 2021 at 5:00:39 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview 2391 - The resolved properties of PAHs at low metallicity Cycle: 1, Proposal Category: GO INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Dr. Julia Christine Roman-Duval (PI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Bruce T. Draine (CoI) Princeton University [email protected] Dr. Karl D. Gordon (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Aleksandra Hamanowicz (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Christopher Clark (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Martha L. Boyer (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Karin Marie Sandstrom (CoI) University of California - San Diego [email protected] Dr. Jeremy Chastenet (CoI) (ESA Member) Ghent University [email protected] OBSERVATIONS Folder Observation Label Observing Template Science Target MIRI IC1613 2 MIRI Imaging (1) IC-1613 6 NIRCam Imaging (1) IC-1613 SEXTANS-A 5 MIRI Imaging (2) SEXTANS-A 9 MIRI Imaging (2) SEXTANS-A 8 MIRI Imaging (2) SEXTANS-A 7 NIRCam Imaging (2) SEXTANS-A ABSTRACT The NIR-MIR SED of galaxies is dominated by spectral features from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) molecules fluorescing in regions illuminated by FUV photons. In low metallicity systems (Z < 0.2 Zo), previous studies with Spitzer have revealed a substantial deficiency in the 1 JWST Proposal 2391 (Created: Tuesday, September 21, 2021 at 5:00:39 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview emission and abundance of PAHs, the origin of which remains unexplained due to the lack of deep, resolved, multi-band photometry or spectroscopy. -

The Recent Star Formation in Sextans a Schuyler D

THE ASTRONOMICAL JOURNAL, 116:2341È2362, 1998 November ( 1998. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE RECENT STAR FORMATION IN SEXTANS A SCHUYLER D. VAN DYK1 Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, California Institute of Technology, Mail Code 100-22, Pasadena, CA 91125; vandyk=ipac.caltech.edu DANIEL PUCHE1 Tellabs Transport Group, Inc., 3403 Griffith Street, Ville St. Laurent, Montreal, Quebec H4T 1W5, Canada; Daniel.Puche=tellabs.com AND TONY WONG1 Department of Astronomy, University of California at Berkeley, 601 Cambell Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411; twong=astro.berkeley.edu Received 5 February 1998; revised 1998 July 8 ABSTRACT We investigate the relationship between the spatial distributions of stellar populations and of neutral and ionized gas in the Local Group dwarf irregular galaxy Sextans A. This galaxy is currently experi- encing a burst of localized star formation, the trigger of which is unknown. We have resolved various populations of stars via deepUBV (RI) imaging over an area with [email protected]. We have compared our photometry with theoretical isochronesC appropriate for Sextans A, in order to determine the ages of these populations. We have mapped out the history of star formation, most accurately for times [100 Myr. We Ðnd that star formation in Sextans A is correlated both in time and space, especially for the most recent([12 Myr) times. The youngest stars in the galaxy are forming primarily along the inner edge of the large H I shell. Somewhat older populations,[50 Myr, are found inward of the youngest stars. Progressively older star formation, from D50È100 Myr, appears to have some spatially coherent structure and is more centrally concentrated. -

Hubble Space Telescope Observer’S Guide Spring 2021

HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OBSERVER’S GUIDE SPRING 2021 In 2021, the Hubble Space Telescope is celebrating 31 years in operation as a powerful observatory probing the astrophysics of the cosmos from Solar system studies to the high-redshift universe. The high-resolution imaging capability of HST spanning the IR, optical, and UV, coupled with spectroscopic capability will remain invaluable through the middle of the upcoming decade. HST coupled with JWST is poised to enable new innovative science and be will be key for multi-messenger investigations. Key Science Threads • Properties of the huge variety of exo-planetary systems: compositions and inventories, compositions and characteristics of their planets • Probing the stellar and galactic evolution across the universe: pushing closer to the beginning of galaxy formation and preparing for coordinated JWST observations • Exploring clues as to the nature of dark energy ACS SBC absolute re-calibration (Cycle 27) reveals 30% greater • Probing the effect of dark matter on the evolution sensitivity than previously understood. More information at of galaxies http://www.stsci.edu/contents/news/acs-stans/acs-stan- • Quantifying the types and astrophysics of black holes october-2019 of over 7 orders of magnitude in size WFC3 offers high resolution imaging in many bands ranging from • Tracing the distribution of chemicals of life in 2000 to 17000 Angstroms, as well as spectroscopic capability in the universe the near ultraviolet and infrared. Many different modes are available for high precision photometry, astrometry, spectroscopy, mapping • Investigating phenomena and possible sites for and more. robotic and human exploration within our Solar System COS COS2025 initiative retains full science capability of COS/FUV out to 2025 (http://www.stsci.edu/hst/cos/cos2025). -

Space Telescope Science Institute Investigators Title

PROP ID: 16100 Principal Investigator: Julia Roman-Duval PI Institution: Space Telescope Science Institute Investigators Title: ULLYSES SMC O7-O9 Giants COS Cycle: 27 Allocation: 8 orbits Proprietary Period: 0 months Program Status: Program Coordinator: Tricia Royle Visit Status Information None PROP ID: 16101 Principal Investigator: Julia Roman-Duval PI Institution: Space Telescope Science Institute Investigators Title: ULLYSES SMC B1 Stars COS Cycle: 27 Allocation: 12 orbits Proprietary Period: 0 months Program Status: Program Coordinator: Tricia Royle Visit Status Information None PROP ID: 16102 Principal Investigator: Julia Roman-Duval PI Institution: Space Telescope Science Institute Investigators Title: SMC B2 to B4 Supergiants COS/STIS Cycle: 27 Allocation: 16 orbits Proprietary Period: 0 months Program Status: Program Coordinator: Tricia Royle Contact Scientist: Sergio Dieterich Visit Status Information None PROP ID: 16103 Principal Investigator: Julia Roman-Duval PI Institution: Space Telescope Science Institute Investigators Title: ULLYSES SMC O Stars COS 1096 Cycle: 27 Allocation: 17 orbits Proprietary Period: 0 months Program Status: Program Coordinator: Tricia Royle Contact Scientist: Julia Roman-Duval Visit Status Information None PROP ID: 16104 Principal Investigator: Julia Roman-Duval PI Institution: Space Telescope Science Institute Investigators Title: ULLYSES UV Pre-imaging of Sextans A and NGC 3109 Targets Cycle: 27 Allocation: 2 orbits Proprietary Period: 0 months Program Status: Program Coordinator: Tricia Royle Visit -

FIRST STELLAR ABUNDANCES in the DWARF IRREGULAR GALAXY SEXTANSA∗ ANDREAS KAUFER European Southern Observatory, Alonso De Cordova 3107, Santiago 19, Chile

ACCEPTED FOR AJ, JANUARY 20, 2004 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 11/26/03 FIRST STELLAR ABUNDANCES IN THE DWARF IRREGULAR GALAXY SEXTANSA∗ ANDREAS KAUFER European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova 3107, Santiago 19, Chile KIM A. VENN Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0HA, UK, and Macalester College, 1600 Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, MN, 55105, USA ELINE TOLSTOY Kapteyn Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box 800, 9700AV Groningen, The Netherlands CHRISTOPHE PINTE École Normale Supérieure, 45 rue d’Ulm, F-75005, Paris, France AND ROLF PETER KUDRITZKI Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA Accepted for AJ, January 20, 2004 ABSTRACT We present the abundance analyses of three isolated A-type supergiant stars in the dwarf irregular galaxy SextansA (= DDO75) from high-resolution spectra obtained with Ultraviolet-Visual Echelle Spectrograph (UVES) on the Kueyen telescope (UT2) of the ESO Very Large Telescope (VLT). Detailed model atmosphere analyses have been used to determine the stellar atmospheric parameters and the elemental abundances of the stars. The mean iron group abundance was determined from these three stars to be h[(FeII,CrII)/H]i = −0.99 ± 0.04 ± 0.061. This is the first determination of the present-day iron group abundances in SextansA. These three stars now represent the most metal-poor massive stars for which detailed abundance analyses have been carried out. The mean stellar α element abundance was determined from the α element magnesium as h[α(MgI)/H]i = −1.09 ± 0.02 ± 0.19. -

Spectroscopy of Pne in Sextans A, Sextans B, NGC 3109 and Fornax 3

Spectroscopy of PNe in Sextans A, Sextans B, NGC 3109 and Fornax Alexei Y. Kniazev1, Eva K. Grebel2, Alexander G. Pramskij3, and Simon A. Pustilnik3 1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Astronomie, K¨onigstuhl 17, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany 2 Astronomisches Institut, Universit¨at Basel, Venusstrasse 7, CH-4102 Binningen, Switzerland 3 Special Astrophysical Observatory, Nizhnij Arkhyz, Karachai-Circassia, 369167, Russia Abstract. Planetary nebulae (PNe) and HII regions provide a probe of the chemi- cal enrichment and star formation history of a galaxy from intermediate ages to the present day. Furthermore, observations of HII regions and PNe permit us to measure abundances at different locations, testing the homogeneity with which heavy elements are/were distributed within a galaxy. We present the first results of NTT spectroscopy of HII regions and/or PNe in four nearby dwarf galaxies: Sextans A, Sextans B, NGC 3109, and Fornax. The first three form a small group of galaxies just beyond the Lo- cal Group and are gas-rich dwarf irregular galaxies, whereas Fornax is a gas-deficient Local Group dwarf spheroidal that stopped its star formation activity a few hundred million years ago. For all PNe and some of the HII regions in these galaxies we have obtained elemental abundances via the classic Te-method based on the detection of the [OIII] λ4363 line. The oxygen abundances in three HII regions of Sextans A are all consistent within the individual rms uncertainties. The oxygen abundance in the PN of Sextans A is however significantly higher. This PN is even more enriched in nitrogen and helium, implying its classification as a PN of Type I. -

Outflow Or Galactic Wind: the Fate of Ionized Gas in the Halos of Dwarf

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 7335 c ESO 2018 October 30, 2018 Outflow or galactic wind: The fate of ionized gas in the halos of dwarf galaxies J. van Eymeren1, D. J. Bomans1, K. Weis1;2, and R.–J. Dettmar1 1 Astronomisches Institut der Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum, Universitatsstraße¨ 150, D-44780 Bochum e-mail: [email protected] 2 Lise Meitner Fellowship Received date; accepted date ABSTRACT Context. Hα images of star bursting irregular galaxies reveal a large amount of extended ionized gas structures, in some cases at kpc-distance away from any place of current star forming activity. A kinematic analysis of especially the faint structures in the halo of dwarf galaxies allows insights into the properties and the origin of this gas component. This is important for the chemical evolution of galaxies, the enrichment of the intergalactic medium, and for the understanding of the formation of galaxies in the early universe. Aims. We want to investigate whether the ionized gas detected in two irregular dwarf galaxies (NGC 2366 and NGC 4861) stays gravitationally bound to the host galaxy or can escape from it by becoming a freely flowing wind. Methods. Very deep Hα images of NGC 2366 and NGC 4861 were obtained to detect and catalog both small and large scale ionized gas structures down to very low surface brightnesses. Subsequently, high-resolution long-slit echelle spectroscopy of the Hα line was performed for a detailed kinematic analysis of the most prominent filaments and shells. To calculate the escape velocity of both galaxies and to compare it with the derived expansion velocities of the detected filaments and shells, we used dark matter halo models. -

Stellar Astrophysics and Exoplanet Science with the Maunakea Spectroscopic Explorer (Mse)

Draft version March 11, 2019 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 STELLAR ASTROPHYSICS AND EXOPLANET SCIENCE WITH THE MAUNAKEA SPECTROSCOPIC EXPLORER (MSE) Maria Bergemann,1 Daniel Huber,2 Vardan Adibekyan,3 George Angelou,4 Daniela Barr´ıa,5 Timothy C. Beers,6 Paul G. Beck,7, 8 Earl P. Bellinger,9 Joachim M. Bestenlehner,10 Bertram Bitsch,1 Adam Burgasser,11 Derek Buzasi,12 Santi Cassisi,13, 14 Marcio´ Catelan,15, 16 Ana Escorza,17, 18 Scott W. Fleming,19 Boris T. Gansicke,¨ 20 Davide Gandolfi,21 Rafael A. Garc´ıa,22, 23 Mark Gieles,24, 25, 26 Amanda Karakas,27 Yveline Lebreton,28, 29 Nicolas Lodieu,30 Carl Melis,11 Thibault Merle,18 Szabolcs Mesz´ aros,´ 31, 32 Andrea Miglio,33 Karan Molaverdikhani,1 Richard Monier,28 Thierry Morel,34 Hilding R. Neilson,35 Mahmoudreza Oshagh,36 Jan Rybizki,1 Aldo Serenelli,37, 38 Rodolfo Smiljanic,39 Gyula M. Szabo,´ 31 Silvia Toonen,40 Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay,20 Marica Valentini,41 Sophie Van Eck,18 Konstanze Zwintz,42 Amelia Bayo,43, 44 Jan Cami,45, 46 Luca Casagrande,47 Maksim Gabdeev,48 Patrick Gaulme,49, 50 Guillaume Guiglion,41 Gerald Handler,51 Lynne Hillenbrand,52 Mutlu Yildiz,53 Mark Marley,54 Benoit Mosser,28 Adrian M. Price-Whelan,55 Andrej Prsa,56 Juan V. Hernandez´ Santisteban,40 Victor Silva Aguirre,57 Jennifer Sobeck,58 Dennis Stello,59, 60, 61, 62 Robert Szabo,63, 64 Maria Tsantaki,3 Eva Villaver,65 Nicholas J. Wright,66 Siyi Xu,67 Huawei Zhang,68 Borja Anguiano,69 Megan Bedell,70 Bill Chaplin,71, 72 Remo Collet,9 Devika Kamath,73, 74 Sarah Martell,75, 76 Sergio´ G. -

Introducción

Annual Report CAB 2018 INTRODUCCIÓN El Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) se fundó en 1999 como un Centro Mixto entre el Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) y el Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (INTA). Localizado en el campus del INTA en Torrejón de Ardoz (Madrid), el CAB se convirtió en el primer centro fuera de los Estados Unidos asociado al recién creado NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI), convirtiéndose en miembro formal en el año 2000. La Astrobiología considera la vida como una consecuencia natural de la evolución del Universo, y en el CAB trabajamos para estudiar el origen, evolución, distribución y futuro de la vida en el Universo, tanto en la Tierra como en entornos extraterrestres. La aplicación del método científico a la Astrobiología requiere la combinación de teoría, simulación, observación y experimentación. Esta aplicación de la Ciencia fundamental a las cuestiones de la Astrobiología es el principal objetivo del CAB. La organización multi- y transdiciplinar del Centro fomenta la interacción de los ingenieros con investigadores experimentales, teóricos y observacionales de varios campos: astronomía, geología, bioquímica, biología, genética, teledetección, ecología microbiana, ciencias de la computación, física, robótica e ingeniería de las comunicaciones. La investigación en el CAB aborda la sistematización de la cadena de eventos que tuvieron lugar entre el Big Bang inicial y el origen de la vida, incluyendo la autoorganización del gas interestelar en moléculas complejas y la formación de sistemas planetarios con ambientes benignos para el florecimiento de la vida. El objetivo final es investigar la posible existencia de vida en otros mundos, reconociendo biosferas diferentes de la terrestre, para ayudarnos en la comprensión del origen de la vida.