Ordinary People Doing the Extraordinary the Story of Ed and Joyce Koupal and the Initiative Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Mile Island Alert Newsletters, 1980

Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Three Mile Island Resources Title: Three Mile Island Alert Newsletters, 1980 Date: 1980 Location: TMI-TMIA Contact: Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] SLAND i 1 V i Three Mile Island Alert February, 1980 Cobalt & Turkeys Collide by MikeT Klinger late Sunday evening, January 13, treatment of radiation exposure on 1-80 north of Pittsburgh, a These reports, she assured me, tractor trailer carrying radio were inaccurate. active cobalt pellets destined Alot of questions remain for use in. a NYC hospital collided unanswered. Why was the story with a trailer load of turkeys. played down so quickly? Why did On Monday morning WHP news the leaking cannister later_____ initially reported a broken cannister was emitting substantial amounts of radiation, .65 Rem/hr. to 4.0 Rem/hr.--"a major health hazard," according to Warren Bassett, administrator of nearby Brookville Hospital. WHP's coverage of the accident decreased and by mid-morning, ’ the story was no longer broadcast. A fifteen-mile stretch of 1-80 was closed off as state police waited for a DER radiation become "a crack in the trailer expert before getting close compartment"? Why was there su< to the truck. The DER expert a large discrepancy in the was stranded due to bad weather figures? Why and how did a and didn't get to the scene "major health hazard" in the until later in the day. The morning become "slight" by the initial dangerous readings of time it hit the Evening News? .65 R/hr. -

Oral History Center University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California East Bay Regional Park District Oral History Project Judy Irving: A Life in Documentary Film, EBRPD Interviews conducted by Shanna Farrell in 2018 Copyright © 2019 by The Regents of the University of California Interview sponsored by the East Bay Regional Park District Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Judy Irving dated December 6, 2018. -

Reel Impact: Movies and TV at Changed History

Reel Impact: Movies and TV Õat Changed History - "Õe China Syndrome" Screenwriters and lmmakers often impact society in ways never expected. Frank Deese explores the "The China Syndrome" - the lm that launched Hollywood's social activism - and the eect the lm had on the world's view of nuclear power plants. FRANK DEESE · SEP 24, 2020 Click to tweet this article to your friends and followers! As screenwriters, our work has the capability to reach millions, if not billions - and sometimes what we do actually shifts public opinion, shapes the decision-making of powerful leaders, perpetuates destructive myths, or unexpectedly enlightens the culture. It isn’t always “just entertainment.” Sometimes it’s history. Leo Szilard was irritated. Reading the newspaper in a London hotel on September 12, 1933, the great Hungarian physicist came across an article about a science conference he had not been invited to. Even more irritating was a section about Lord Ernest Rutherford – who famously fathered the “solar system” model of the atom – and his speech where he self-assuredly pronounced: “Anyone who expects a source of power from the transformation of these atoms is talking moonshine.” Stewing over the upper-class British arrogance, Szilard set o on a walk and set his mind to how Rutherford could be proven wrong – how energy might usefully be extracted from the atom. As he crossed the street at Southampton Row near the British Museum, he imagined that if a neutron particle were red at a heavy atomic nucleus, it would render the nucleus unstable, split it apart, release a lot of energy along with more neutrons shooting out to split more atomic nuclei releasing more and more energy and.. -

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All Rights Reserved

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All rights reserved. Public Citizen Foundation 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 www.citizen.org ISBN: 978-1-58231-099-2 Doyle Printing, 2016 Printed in the United States of America PUBLIC CITIZEN THE SENTINEL OF DEMOCRACY CONTENTS Preface: The Biggest Get ...................................................................7 Introduction ....................................................................................11 1 Nader’s Raiders for the Lost Democracy....................................... 15 2 Tools for Attack on All Fronts.......................................................29 3 Creating a Healthy Democracy .....................................................43 4 Seeking Justice, Setting Precedents ..............................................61 5 The Race for Auto Safety ..............................................................89 6 Money and Politics: Making Government Accountable ..............113 7 Citizen Safeguards Under Siege: Regulatory Backlash ................155 8 The Phony “Lawsuit Crisis” .........................................................173 9 Saving Your Energy .................................................................... 197 10 Going Global ...............................................................................231 11 The Fifth Branch of Government................................................ 261 Appendix ......................................................................................271 Acknowledgments ........................................................................289 -

Mike Gravel; an Posed Act, Arguments Pro and Con

911 P.2d 389 Page 1 128 Wash.2d 707, 911 P.2d 389 (Cite as: 128 Wash.2d 707, 911 P.2d 389) [2] Statutes 361 320 Supreme Court of Washington, En Banc. 361 Statutes 361IX Initiative PHILADELPHIA II, a nonprofit corporation; 361k320 k. Ballot Title, Description of Pro- Robert D. Adkins, an individual; Mike Gravel; an posed Act, Arguments Pro and Con. Most Cited individual, Petitioners, Cases v. Christine O. GREGOIRE, Attorney General of the Attorney General must prepare ballot title and State of Washington, Appellant. summary regardless of content of initiative. West's RCWA 29.79.040. No. 62663-4. Feb. 29, 1996. [3] Statutes 361 227 Supporters of initiative filed suit against Attor- 361 Statutes ney General, seeking writ of mandamus ordering 361VI Construction and Operation her to prepare ballot title. The Superior Court, 361VI(A) General Rules of Construction Thurston County, Wm. Thomas McPhee, J., dis- 361k227 k. Construction as Mandatory or missed action. Supporters appealed. The Supreme Directory. Most Cited Cases Court granted review. The Supreme Court, Rosselle Pekelis, J. pro tem., held that: (1) Attorney General Statutory term “shall” is presumptively imper- did not have discretion to refuse to prepare ballot ative unless contrary legislative intent is apparent. title and summary, and (2) initiative which had as [4] Constitutional Law 92 2451 its fundamental purpose creation of federal initiat- ive process was beyond scope of Washington's ini- 92 Constitutional Law tiative power. 92XX Separation of Powers 92XX(C) Judicial Powers and Functions Affirmed. 92XX(C)1 In General West Headnotes 92k2451 k. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

1 the Politics of Independence: the China Syndrome (1979)

1 The Politics of Independence: The China Syndrome (1979), Hollywood Liberals and Antinuclear Campaigning Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia Abstract: This article draws, among other things, on press clippings files and scripts found in various archives to reconstruct the complex production history, the marketing and the critical reception of the nuclear thriller The China Syndrome (1979). It shows that with this project, several politically motivated filmmakers, most notably Jane Fonda, who starred in the film and whose company IPC Films produced it, managed to inject their antinuclear stance into Hollywood entertainment. Helped by the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant two weeks into the film’s release, The China Syndrome gained a high profile in public debates about nuclear energy in the U.S. Jane Fonda, together with her then husband Tom Hayden, a founding member of the 1960s “New Left” who had entered mainstream politics in the California Democratic Party by the late 1970s, complemented her involvement in the film with activities aimed at grass roots mobilisation against nuclear power. If the 1979 Columbia release The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979) is remembered today, it is mainly because of an astonishing coincidence. This thriller about an almost catastrophic accident at a nuclear power plant was released just twelve days before eerily similar events began to unfold at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant near Harrisburg in Pennsylvania on 28 March 1979, resulting in, as the cover of J. Samuel Walker’s authoritative account of the event calls it, “the worst accident in the history of commercial nuclear power in the United States” (Walker). -

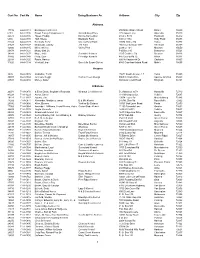

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Citizenworks.Pdf

Biennual Report 2003-2004 CITIZEN WORKS develops systemic means to advance the citizen movement in three ways: first, we enhance the work of existing organizations by helping to share information, build coalitions, and institute improved mechanisms for banding activists together; second, we bring new energy and support to the progressive movement by recruiting, training, and activating citizens around important problems; and third we incubate groups and act as catalysts where there are too few public interest voices. To meet these goals, Citizen Works runs multiple, integrated programs. The highlights from 2003-2004 are listed inside. I. The Corporate Reform Campaign ......................... 3 II. Incubation Program ................................... 7 III. Strengthening the Progressive Movement .............. 8 IV. Summer Speakers Series ............................... 10 V. The People’s Business ................................. 11 Citizen Works People ..................................... 12 Resources ................................................ 13 Appendices ............................................... 14 How to Help .............................................. 18 I. The Corporate Reform Campaign Our main focus in 2003-2004 was our Corporate Reform Campaign, which began in 2002 in response to the Enron scandal and continues to be a leading voice in developing corporate reform movement. The goal of Citizen Works’ Corporate Reform Campaign is to work with citizens across the country to correct the cur- rent destructive course of our political economy. We educate about the shift from unsustainable market-driven values to sustainable life-affirming values, a shift from a society where corporations dominate to one in which people recognize their capacities as citizens to exert sovereign control over the behavior of publicly-chartered corporations. Although many citizens understand that corporate power poses a threat, few understand what, if any- thing, can be done to challenge excessive corporate power in a constructive manner. -

Titel Kino 2-2000

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 2/2000 At the Cannes International Film Festival: THE FAREWELL by Jan Schütte LOST KILLERS by Dito Tsintsadze NO PLACE TO GO by Oskar Roehler VASILISA by Elena Shatalova THE TIN DRUM – A LONE VICTOR On the History of the German Candidates for the Academy Award »SUCCESS IS IN THE DETAILS« A Portrait of Producer Kino Andrea Willson Scene from “THE FAREWELL” Scene from Studio Babelsberg Studios Art Department Production Postproduction Studio Babelsberg GmbH August-Bebel-Str. 26-53 D-14482 Potsdam Tel +49 331 72-0 Fax +49 331 72-12135 [email protected] www.studiobabelsberg.com TV SPIELFILM unterstützt die Aktion Shooting Stars der European Filmpromotion www.tvspielfilm.de KINO 2/2000 German Films at the 6 The Tin Drum – A Lone Victor 28 Cannes Festival On the history of the German candidates for the Academy Award 28 Abschied for Best Foreign Language Film THE FAREWELL Jan Schütte 11 Stations Of The Crossing 29 Lost Killers Portrait of Ulrike Ottinger Dito Tsintsadze 30 Die Unberührbare 12 Souls At The Lost-And-Found NO PLACE TO GO Portrait of Jan Schütte Oskar Roehler 31 Vasilisa 14 Success Is In The Details Elena Shatalova Portrait of Producer Andrea Willson 16 Bavarians At The Gate Bavaria Film International 17 An International Force Atlas International 18 KINO news 22 In Production 22 Die Blutgräfin 34 German Classics Ulrike Ottinger 22 Commercial Men 34 Es geschah am 20. Juli Lars Kraume – Aufstand gegen Adolf Hitler 23 Edelweisspiraten IT HAPPENED ON JULY 20TH Niko von Glasow-Brücher G. W. -

World Constitutional Convention. Appropriation

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Initiatives California Ballot Propositions and Initiatives 12-20-1993 World Constitutional Convention. Appropriation. Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/ca_ballot_inits Recommended Citation World Constitutional Convention. Appropriation. California Initiative 617 (1993). http://repository.uchastings.edu/ca_ballot_inits/775 This Initiative is brought to you for free and open access by the California Ballot Propositions and Initiatives at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Initiatives by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELECTIONS DIVISION (916) 445-0820 Office of the Secretary of State 1230 J Street March Fong Eu Sacramento, California For Hearing and Speech Impaired Only: (800) 833-8683 r " #617 December 20, 1993 Pursuant to Section 3513 of the Elections Code, we transmit a copy of the Title and Summary prepared by the Attorney General on a proposed I-'~' Measure entitled: WORLD CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION. TION. INITIATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT o STATUTE .. Circulating and Filing Schedule 1. Minimum number of signatures required ...•...•.•. ....•...•.•..••.. 615,958 Cal. Const., Art. II, Sec. 8(b). 2. Official Summary Date G • • • • • • • • • • • , • • • • • • • • • • . ......... ~M~0~n~da~y~,_1~2~/:2~0/~9~3 Elec. C., Sec. 3513. 3. Petition Sections: a. First day Proponent can circulate Sections for signatures •..........••...•••...••.. .......... Monday, 12/20{93 Elec. C., Sec. 3513. b. Last day Proponent can circulate and file with the county. All sections are to be filed at the same time within each county . • . •. ....... Wednesday, 05/1 8194 Elec. C., Secs. -

The National Initiative Proposal: a Preliminary Analysis, 58 Neb

Nebraska Law Review Volume 58 | Issue 4 Article 3 1979 The aN tional Initiative Proposal: A Preliminary Analysis Ronald J. Allen University of Iowa College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Ronald J. Allen, The National Initiative Proposal: A Preliminary Analysis, 58 Neb. L. Rev. 965 (1979) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol58/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. By Ronald J. Allen* The National Initiative Proposal: A Preliminary Analysis I. INTRODUCTION ................................................. 966 II. THE INITIATIVE'S POTENTIAL CONTRIBUTION TO THE POLITICAL STRUCTURE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ....................................... 969 A. Democratic Theory and the Federal Government .................... 969 B. The Unrepresentative Tendencies of the Federal Government ............................................. 978 1. Public Opinion............................................. 980 2. The Effect of Organized Interest Lobbying .................................................. 983 3. The Legislative Processin Operation....................... 985 4. Congress: The Electoral Connection ........................ 988 5. The Nature of Congressional Unrepresentativeness .....................................