Me and My Words of Hiralal Jain Shastri of Sadumar.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Fo'ks"K Vfkzlgk¸; ;Kstusarxzr Ykhkkf;Kzaph ;Knh

fo'ks"k vFkZlgk¸; ;kstusarxZr ykHkkF;kZaph ;knh ;kstusps uko%& Jko.kckG lsok jkT; fuo`Rrh osru ;kstuk v-Ø- ykHkkF;kZps uko rkyqD;kps uko 1 Abdul Ajij Qureshi e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 2 Abdul Gaffar Abdul Rajjak e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 3 Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahim e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 4 Abdul Saiyyad Abdul Majid e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 5 Abidabi Abdul Rashid e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 6 Anandrao Janba Nikhar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 7 Asha Bi Usman Khan e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 8 Balkrishna Kashiram Khapekar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 9 Bapurao Diwalu Bhishikar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 10 Bhure Khan Ashraf Khan e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 11 Bitti Narayan Shriwastav e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 12 Chagunabai Gyanshyam Kasture e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 13 Chintaman Marotrao Ahirkar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 14 Devkabai Narayan Dharmik e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 15 Diwalu Mahadeorao Dharmik e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 16 Fagunrao Ramkisan Paunikar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 17 Gajanan Govind Adyalkar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 18 Gangubai Laxmanrao Dobarkar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 19 Ganpati Kisanuji Paunikar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 20 Gayabai Timji Kodape e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 21 Ghanshyam Gangaram Umrikar e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 22 Ghanshyam Ganpat Korde e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 23 Ghanshyam Karu Kasture e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 24 Gulam Rasool Abdul Rajjak e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj e/; foHkkx 25 Gulam Rasool Shaikh Najir e-u-ik-{ks= ukxiwj -

Unclaimed-Dividend-2

STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDED AMOUNT FOR THEYEAR 2012-13 WARRANT NO. FOLIO NO. NAME AMOUNT 91 000006 T V PRASADA RAO 1,040.00 107 00000777 MUKESHKUMAR BALCHAND SANGHAVI 400.00 115 00000946 BHUSHAN LAL CHADHA 400.00 132 00001132 ANUP RAMCHAND RADHAKRISHNANI 80.00 158 00001626 ISHWARA RAMA BHAT 24.00 172 000019 RAMAKRISHNA TUMMALA 800.00 181 00001973 SANDEEP DAGHDU SHINDE 200.00 190 00002109 MUKESHKUMAR BALCHAND SANGHVI HUF 800.00 203 000024 VANKATA RAO GUDURU 1,760.00 232 00002988 CHANDRAKANT RAMDAS PATIL 196.00 275 00003732 DEVENDRA ZARKAR 400.00 308 00004509 MANJI JADAVA PINDORIYA 400.00 310 00004522 ROHIT CHAWLA 40.00 321 00004853 S.D.GUNASEKARAN . 80.00 337 00005482 PRATAP KHANNA 200.00 401 00007152 INDU MITHAL 160.00 481 00009379 MANJU JOHARI 80.00 486 00009457 REKHABEN KAMLESH MODI 40.00 487 00009542 SAMAY PAL SINGH 400.00 539 00010597 MINABEN MUKESHKUMAR GOPANI 80.00 541 00010711 MOKA PRAKASH 40.00 584 000119 MANISH AGARWAL 400.00 591 00012094 VIJAY KUMAR JAIN 80.00 626 00013711 K KRISHNA RAO 400.00 642 000144 VINAY GUPTA 400.00 645 00014473 SUNITA SHARMA 80.00 646 000145 VIKAS GUPTA 400.00 659 00014904 BAKKAM LAXMAN 200.00 665 00015087 PRADIP LALCHAND SHAH 80.00 667 00015121 RAJKANVAR SARDA . 16.00 671 00015312 PADMA SAILAJA CHITLURI 800.00 687 00015881 SHANKER LAL LADDHA 12.00 689 00015936 TUMULURI ACHUTHA JANARDHAN RAO 40.00 690 00015951 Kanchedilal Jain 400.00 706 000165 CHANDER NARULA 400.00 708 000166 RAM SARUP KHANNA 400.00 722 000171 RUCHITA SABHARWAL 400.00 727 00017249 MADHU SUDAN KUMAR 800.00 738 00017685 ARNAVAZ BEJI BUHARIWALA 20.00 747 00018025 PRAVINBHAI BALUBHAI POKIYA 80.00 755 00018518 BHASKARA RAO DANGETI 80.00 760 00018713 PRADEEP MITTAL 200.00 766 00019178 VIMALA DEVI 400.00 767 00019199 SUMEET KUMAR BATRA 80.00 784 000201 S PASCAL 400.00 785 00020153 AJIT KUMAR S. -

DAILY BOARD FOR: 23.07.2019 (Tuesday) Login

1 DAILY BOARD FOR: 23.07.2019 (Tuesday) Login: www.hcbanagpur.com. %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% IN THE COURT OF HON'BLE SHRI JUSTICE V.M. DESHPANDE APPELLATE SIDE-CRIMINAL 23/07/2019 C. R. No. : Floor : First Floor. Building : Main NOTE : CRIMINAL MATTERS WILL BE TAKEN UP AFTER THE COMPLETION OF CIVIL BOARD. * FOR ORDERS [CRIMINAL SIDE MATTERS] * 11 APEAL/281/2007 ANAND SUDARS # STATE OF M MP KHAJANCHI # APP AH:ORDERS [C/F APPELLANT HAS NOT COLLECTE D PAPER BOOK AS YET] WITH R & P [ACCUSED IS ON BAIL] 12 APEAL/299/2007 D SURESH S/O # THE STATE RM DAGA, MP KHAJANCHI & N BURILE # APP OF:ORDERS [C/F APPELLANT HAS NOT COLLECTE D PAPER BOOK AS YET] WITH R & P [ACCUSED IS ON BAIL] 13 APEAL/343/2007 / SUSHIL S/O # STATE OF M RAJNISH VYAS AND SA GIR P ] # APP AH:ORDERS [C/F APPELLANT HAS NOT COLLECTE D PAPER BOOK AS YET] WITH R & P [ACCUSED IS ON BAIL] %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% IN THE COURT OF HON'BLE SHRI JUSTICE ROHIT BABAN DEO APPELLATE SIDE-CRIMINAL 23/07/2019 C. R. No. : " G " Floor : First Floor. Building : Main * FOR ORDERS [CRIMINAL SIDE MATTERS] * --------------------------------------- 1 APL/174/2018 DR. ANITA W/ # DR. SAVITA R AMOL MOHAN JALTARE DHANANJAY MAROTRAO :ORDERS ON APPP/1133/19 RESTORATION OF A SHER R ] # JEMINI BRIJMOHAN KASAT /R-1 PL/174/18 (D). [SHRI. AMOL M. JALTARE ADV . APPLICANT HAS DEPOSITED COST OF RS. 30 00/- IN H.C.L.S. VIDE RECEIPT NO. 4788939 DT. 27/6/2019] APPP/1133/2019 DR. ANITA W/ # DR. SAVITA AMOL MOHAN JALTARE # R: APL/174/2018 # : -- 2 APL/978/2018 HARI PRAKASH # SHAILESH S/O VIRAT SURENDRA MISHRA KAUSTUBH DEOGADE :ORDERS ON APPP/2148/18 GRANT OF TIME TO SACHIN P. -

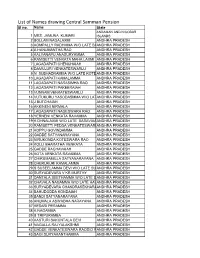

List of Names Drawing Central Samman Pension Sl No

List of Names drawing Central Samman Pension Sl no. Name State ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 MRS. JAMUNA KUMARI ISLANDS 2 BOLLAM NAGALAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 3 KOMPALLY RADHMMA W/O LATE BAANDHRA PRADESH 4 A HANUMANTHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 5 KALYANAPU ANASURYAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 6 RAMISETTI VENKATA MAHA LAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 7 LAGADAPATI CHENCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 8 DAMULURI VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 9 N SUBHADRAMMA W/O LATE KOTEANDHRA PRADESH 10 LAGADAPATI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 11 LAGADAPATI NARASIMHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 12 LAGADAPATI PAKEERAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 13 VUNNAM VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 14 VUTUKURU YASODASMMA W/O LATANDHRA PRADESH 15 J BUTCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 16 AKKINENI NIRMALA ANDHRA PRADESH 17 LAGADAPATI NAGESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 18 YERNENI VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 19 K DHNALAXMI W/O LATE BASAVAIAANDHRA PRADESH 20 RAMISETTI PEDDA VENKATESWARLANDHRA PRADESH 21 KOPPU GOVINDAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 22 GADDE SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 23 NIRUKONDA KOTESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 24 KOLLI BHARATHA VENKATA ANDHRA PRADESH 25 GADDE RAGHAVAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 26 KOTA VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 27 CHIRUMAMILLA SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 28 CHERUKURI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 29 S SUSEELAMMA DEVI W/O LATE SU ANDHRA PRADESH 30 SURYADEVARA V KR MURTHY ANDHRA PRADESH 31 DANTALA SEETHAMMA W/O LATE DANDHRA PRADESH 32 CHAVALA NAGAMMA W/O LATE HAVANDHRA PRADESH 33 SURYADEVARA CHANDRASEKHARAANDHRA PRADESH 34 BAHUDODDA KONDAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 35 BANDI SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 36 ANUMALA ASWADHA NARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 37 KESARI PERAMMA ANDHRA -

Evaluation of Problems and Prospects of Installing

“COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EFFECT OF NIRGUNDI PATRA PINDA SWEDA AND NADISWEDA IN KATISHOOL .” A thesis submitted to Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) In Panchakarma Subject Under the Board of Ayurveda Studies Submitted By RAVIKUMAR BHAGAWAN PATIL. Under the Guidance of Dr. R.R. GAYAL DECEMBER-2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “Comparative study of effect of Nirgudi Patra Pinda Sweda and Nadisweda in Katishool .” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in department of Ayurveda of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Shri. Ravikumar Bhagawan Patil under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other university or examining body upon him. Place: Pune Dr.Gayal R.R. Prof.and H.O.D.Kayachikitsa Dept. Date : Research Guide ACKNOWLEDGEMENT. It gives me immense pleasure to offer my sincere thanks to all those who have rendered their wholehearted support, guidance and cooperation in completing my work. I express my deep hearted reverence to that divine source. I bow my head to the lotus feet of Lord Dhanvantri with whose showering of blessings this task was ventured without any hindrances. It’s my great pleasure to express my deep gratitude towards my adorable guide-supervisor, Dr. R.R.Gayal, professor, for her incessant and untiring guidance with all the diligence. -

05 All Component All 07082017.Xlsx

IDD ComponentNameApp_No Name Father_Name Adhar_No 28091 BLC (NC) APP27802814453866 AABA BAPURAO CHOUDHARI AABA BAPURAO CHOUDHARI 28092 BLC (NC) APP27802814422605 AABASAHEB GOVERDHAN KAMBLE GOVERDHAN KAMBLE ******457196 28093 BLC (NC) APP27802814456347 AABEDA MOHAMMAD SHAIKH MOHAMMAD SHAIKH 28094 BLC (NC) APP27802814453989 AADAMBI HAJI SIPAE RAJAKSAB SIPAE 28095 BLC (NC) APP27802814189782 AADESH JAYRAM NIKAM JAYRAM NIKAM 28096 BLC (NC) APP27802814420783 Aadhika Tushar Jagtap Kalidas Hadge ******071417 28097 BLC (NC) APP27802814438339 AADITYA CHANDRAKANT PATHADE CHANDRAKANT ******930261 28098 BLC (E) APP27802814409550 Aadrawati Vishwakarma Motilal 28099 BLC (NC) APP27802814417098 AAGAZ SAGIR SHAIKH SAGIR ******798021 28100 BLC (NC) APP27802814407259 AAKANSHA AVINASH RAWOOL GOPAL ANANT RAWOOL ******425298 28101 BLC (NC) APP27802814413784 Aalakrao Shashirao Kamble Shashirao Kamble ******916653 28102 BLC (NC) APP27802814458722 aalanki shakti marpale shakti marpale 28103 BLC (NC) APP27802814404863 Aalim Abdulhamid Patel Abdulhamid Sherfodin Patel ******771825 28104 BLC (NC) APP27802814452180 AAMIR SHABUDUIN TABOLI SHABUDUIN TABOLI ******848890 28105 BLC (NC) APP27802814453540 AAMNA KHURSHID BAGBAN KHURSHID BAGBAN 28106 BLC (NC) APP27802814451413 AAMOL JANDHIN NAVLE JANDHIN NAVLE ******870122 28107 BLC (E) APP27802814447915 AANANTA SADASHIV BHAVEKAR SADASHIV BHAVEKAR ******788485 28108 BLC (NC) APP27802814452317 AANJANA SHANKAR HARALE SHANKAR TAMMA HARALE ******015301 28109 BLC (E) APP27802814470945 AANNA KALURAM NIMBALKAR KALURAM NIMBALKAR ******327472 -

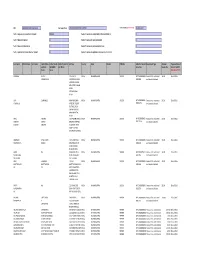

Apcotex 08-09

CINL99999MH1986PLC039199 Company Name APCOTEX INDUSTRIES LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD‐MON‐YYYY) 28‐JUN‐2013 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 394148 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husba Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First nd Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD‐MON‐YYYY) A RAJESH A S K V C/O A S K V INDIA MAHARASHTRA 999999 APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed 16.00 26‐Jul‐2016 ANJANEYULU ANJANEYULU SHRI 0025993 and unpaid dividend LAKSHMI GANESH MILL STORES MAIN ROAD PEDDAPURAM INDIA AJAY GAMANLAL MAHAVIR GNAN INDIA MAHARASHTRA 999999 APCO00000000 Amount for unclaimed 24.00 26‐Jul‐2016 GAMANLAL APTS 3RD FLOOR 00000272 and unpaid dividend FLAT NO 28 SAI SAGAR VASAI (E) MAHARASHTRA INDIA AKAL PADAM C/O PADAM CHAND INDIA MAHARASHTRA 999999 APCO00000000 Amount for unclaimed 20.00 26‐Jul‐2016 KANWAR CHAND SINGHVI CHHIPON 00010832 and unpaid dividend SINGHVI SINGHVI KA CHOWK NEAR ASOP KI HAVELI JODHPUR RAJ INDIA AMARJEET ITPAL SINGH C/O S AMRITPAL INDIA MAHARASHTRA 999999 APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed 36.00 26‐Jul‐2016 KAUR BAGGA BAGGA SINGH BAGGA 45 0005516 and unpaid dividend KADBI CHOWK NAGPUR INDIA AMIR NA KHAN MANZIL B‐ INDIA MAHARASHTRA 999999 APCOIN3005051 Amount for unclaimed 36.00 26‐Jul‐2016 NOORMOHA ROAD PACHGANI 0201453 and unpaid dividend MED KHAN DIST. -

Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend

AMOUNT FOR UNCLAIMED AND UNPAID DIVIDEND Proposed Date of Amount transfer to Investor First Name Investor Last Name Address State District Pin Code Folio Number transferre IEPF d (DD-MON- YYYY) ARCHANA DOSI C/O M K DOSI,ASSTT. GENERAL MANAGER,KUTESHWAR LIMESTONE MINE PO,GAIRTALAI BARHI KATN MADHYA PRADESH KATNI FOLIOA000745 5.00 18-SEP-2019 ANNAMMA ABRAHAM KARIMPIL HOUSE PANGADA PO,PAMPADY KOTTAYAM DT,KERALA STATE, KERALA KOTTAYAM FOLIOA002266 25.00 18-SEP-2019 ARVINDKUMAR AGARWAL C/O VINOD PUSTAK MANDIR,BAG MUZAFFAR KHAN,AGRA-2, UTTAR PRADESH AGRA FOLIOA002410 5.00 18-SEP-2019 ANIL KUMAR C/O DIAMOND AND DIAMOND,TAILORS & DRAPPERS SHOP NO 5,LAL RATTAN MARKET NAKODAR ROAD,JALANDHAR PUNJAB JALLANDHAR FOLIOA002592 35.00 18-SEP-2019 ANIRUDDH PAREKH FRANKLIN GREENS APTS,26 L 1 JFK BLDV,SOMERSET,N.J 08873 USA NA NA FOLIOA006562 50.00 18-SEP-2019 ATUL THAKKAR 16 HARI NIWAS,2ND FLOOR PT DIN DAYAL ROAD,OPP GANESH TEMPLE,DOMBIVLI (W) THANE MAHARASHTRA THANE FOLIOA006631 100.00 18-SEP-2019 ASHOK PODDAR C/O KHETSIDAS RAMJIDAS,178 M G ROAD,CALCUTTA - 7, WEST BENGAL KOLKATA FOLIOA006781 3.00 18-SEP-2019 ALABHAI DHOKIA C/O RAMABEN ALABHAI DEDHIA,MITRAKUT SOCIETY "PRATIK",NR GRUH VIHAR SOC NR PTC,GROUND JUNAGADH GUJARAT JUNAGADH FOLIOA007370 10.00 18-SEP-2019 ANUJ BOTHRA X,X,,0 MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI FOLIOA007489 8.00 18-SEP-2019 B NAGARAJAPPA # 763/B 2ND CROSS,M B SHANKARAPPA LAYOUT,,TIPTUR KARNATAKA TIPTUR FOLIOB000036 15.00 18-SEP-2019 BHAGWANDAS KUNDALIA 69 DATTATRAYA COLONY,MORA BHAGAL CHAR RASTA RANDER,SURAT-5, GUJARAT SURAT FOLIOB000382 8.00 18-SEP-2019 -

Sudarshan Chemical Industries Limited 162 Wellesley Road, Pune ‐ 411 001

SUDARSHAN CHEMICAL INDUSTRIES LIMITED 162 WELLESLEY ROAD, PUNE ‐ 411 001 Listi of Shareholders whose Interim Dividend for FY 2019‐20 is unpaid / unclaimed Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number DP Id‐Client Id‐ Unclaimed Account Amount Number A ANURADHA 11‐5‐453, F‐31 SRI SAI INDIA Andhra Pradesh 500004 SUDA0000000 6300.00 KRUPA APTS. RED HILLS 000A02697 HYDERABAD A ARUMUGASAMY BHARAT OFFSET INDIA MAHARASHTRA 444444 SUDA0000000 11781.00 PRINTERS 15 MEERA 000A00600 HUSAIN ST SIVAKASI A G NAIR RAM MEENA INDIA Kerala 682016 SUDA0000000 945.00 VALANJAMBALAM, 000A00855 COCHIN A GUNASEKARAN 31 BALAJI NAGAR 1ST INDIA Tamil Nadu 600014 SUDA0000000 2331.00 STREET ROYAPETTAH 000A00895 CHENNAI A K CHANDRASEKARAN C‐147, II CROSS STREET INDIA Tamil Nadu 600082 SUDA0000000 4725.00 JAWAHAR NAGAR 000A00771 CHENNAI A K PSCONSULTANTSPV C/O RPS SIDHU HOUSE INDIA Chandigarh 160010 IN300513‐ 819.00 TLTD NO 549 SECTOR 10 A 23467671‐0000 CHANDIGARH CHANDIGARD A K SMUTHUSAMY 3/3 RAMNAGAR 4TH INDIA Tamil Nadu 638602 SUDA0000000 2331.00 STREET TIRUPUR 000A00879 A KRISHNAMURTI 19 III BLOCK INDIA Karnataka 560011 SUDA0000000 1575.00 JAYANAGAR 000A00823 BANGALORE A N KRISHNAN NO 83/240‐4 (190/A) INDIA Karnataka 560075 SUDA0000000 1890.00 IST CROSS CHURCH 000A02251 STREET NEW THIPPASANDRA BANGALORE A PALANISAMY M/S KALAIVANI DYEING INDIA Tamil Nadu 638601 SUDA0000000 2331.00 FACTORY 1ST STREET 000A00881 PETHICHETTY PURAM TIRUPUR A R SHANTHA 13/1,7TH MAIN ROAD INDIA Karnataka 560019 SUDA0000000 1575.00 9TH CROSS N R COLONY 000A02098 BANGALORE A VIJAYASEKARAN C/O SAFIRE PRINTING INDIA Tamil Nadu 626123 SUDA0000000 2331.00 INKS N R K 000A00894 RAJARATNAM ROAD SIVAKASI ABDUL QADIR ABDULGANI SHIVPRASAD BUILDING INDIA Maharashtra 400052 IN300513‐ 252.00 2ND FLOOR FLAT NO 21 84058646‐0000 S V ROAD OLD KHAR WEST MUMBAI MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA ABDUL QADIR ABDULGANI SHIVPRASAD BUILDING INDIA Maharashtra 400052 12019101‐ 315.00 IInd FLOOR FLAT NO‐ 00560855‐SU00 21, S.V. -

Sr.No. Worker's Name

Pune Sr.No. Worker’s Name 1 BHARATI BHARAT VARANKAR 2 REWALE NIRMALA AMIT 3 MANE JYOTI SIDDHESHWAR 4 REWALE PALLAVI ATUL 5 BHARAT NITIN NAIDU 6 MEERY TRIMALYA GANDHI 7 BHARAT HANUMANT AHIWALE 8 SANTOSH DASHRATH SHINDE 9 SHOHEB KHAN SARGARAJ KHAN KAGDI 10 MANOHARLAL CHENARAM LAL 11 LAXMAN KUNDALIK VIDHATE 12 PANDURANG SHANKAR MALI 13 ROHINI GOVIND MANE 14 ALI ASAGAR KUNNU 15 TUKARAM TRIBAK GHADAGE 16 VINOD KISHOR GHORPADE 17 JAYASHRI TANAJI CHAVAN 18 SANTOSHA HAOYALAPPA 19 BHAGYASHREE BALU CHIDRE 20 DHANASHRI DHANENDRA KULKARNI 21 BHAUSAHEB MARUTI DAWANE 22 YUVRAJ EKNATH WAGHMARE 23 RAKHI HANUMANT POL 24 BHARAT NILIKANTH SARWAN 25 AMARNATH RAMSHIGHASON GIRI 26 SADASHIV KONDIBA CHAVAN 27 VIJAYA SANTOSH KAMBLE 28 SUVARNA POPAT ADAGALE 29 NEELAM ANIL NETKE 30 KAMBLE SANTOSH SUDAM 31 SACHIN NARAYAN BHISE 32 SUREKHA GANESH ADGALE 33 SWATI LAKHAN LANGAR 34 BHAGYASHRI GAJANAN KULKARNI 35 SWATI SATISH SHINDE 36 VRUSHALI SHEKHAR JOSHI 37 NEMI CHAND 38 SHEETAL PRAVEEN DHADAVE 39 SHELAKE ASHA RAKHMAJI 40 SAROJA SHREEHARI SHINDE 41 YASHWANT MUGA SABALE 42 SHATRUGHNA GANESH TUPE 43 RAMESH BABAN KAPSE 44 JYOTI RAMDAS DHOUGULE 45 SANGITA DNANOBA MOKASHI 46 RUKHMINA KESHAV GHUGE 47 SUVARNA RAMESH SANAS 48 SAKHUBAI VALU RATHOD 49 SANGITA VASANT SHEDE 50 DIGAMBAR BALIRAM SUTAR 51 PARMESHWAR DEVIDAS DHAGE 52 DHANANJAY KHANDU SAWAI 53 BHAUSAHEB TUKARAM SHIDE 54 GOKUL CHANDAR GAIKWAD 55 HANIMA AKBAR SHAIKH 56 SHIVAJI NAGURAO SASANE 57 ASHA BABAN TAMBE 58 LAXMI VISHNU ASWARE 59 SARASWATI RAVI KAMBLE 60 HULGE SUNANDA SHIVAJI 61 HULGE BALU MAHADU 62 BHISE NITIN -

Mac Charels (India) Limited Unpaid Dividend As on 31-03-2020 for the Financial Year 2016-2017 SL NO BENEFICIARY NAME FOLIO

Mac Charels (India) Limited Unpaid Dividend as on 31-03-2020 For The Financial year 2016-2017 SL NO BENEFICIARY NAME FOLIO WARRANT NO NET AMOUNT 1 AJIT SINGH DHILLON A0002227 20170001 1000.00 2 HANSRAJ RAGHAV HIRANI H0001045 20170003 1000.00 3 MAJ. ARMINDER PAL SINGH C0000706 20170004 1000.00 4 RANI SOOD R0000707 20170005 2000.00 5 HARI PRAKASH GUPTA H0001456 20170007 2000.00 6 AJAY PURI A0001397 20170008 1000.00 7 BRIJ GUPTA B0001900 20170009 1000.00 8 SAVITA AGRAWAL S0001830 20170010 1000.00 9 SUNITA DHANDIA S0002394 20170011 1000.00 10 S L ARORA S0002486 20170012 1000.00 11 SUSHMA BAHL S0004298 20170013 1000.00 12 ASIF YUNUS A0001417 20170015 1000.00 13 ANITA MATHUR A0010152 20170016 4000.00 14 DESH BANDHU NASA D0000586 20170017 1000.00 15 HARBANSAL SHANI H0000565 20170018 1000.00 16 JAWAAHAR VARMA J0001037 20170019 1000.00 17 KIRAN SYAL K0001443 20170020 2000.00 18 NAHAR SINGH GHUMAN N0000569 20170022 1000.00 19 NEELAM MALIK N0001119 20170023 1000.00 20 NIRMAL KUMAR DHANDIA N0001110 20170024 1000.00 21 NARENDER KHARBANDA N0001751 20170025 1000.00 22 PEUSH GARG P0001547 20170029 1000.00 23 N RAMANATHAN N0001109 20170030 1000.00 24 KAVITA KAUSHIK K0000632 20170032 1000.00 25 GAJENDRA KUMAR BADOLA G0010017 20170033 3000.00 26 AMAR NATH CHOPRA A0001139 20170035 1000.00 27 DAYAL DASS SURI D0001616 20170036 1000.00 28 GOVIND SINGH CHAUHAN G0000544 20170039 1000.00 29 BUDHI MATI GUPTA B0001778 20170040 1000.00 30 SANJIV KUMAR S0000699 20170041 1000.00 31 SATISH K PIPLANI S0000736 20170042 500.00 32 ASHOK KUMAR A0001119 20170043 1000.00 33