An Argument for Investigation Into Collaborative, Choreomusical Relationships Within Contemporary Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics

Smith ScholarWorks Dance: Faculty Publications Dance 6-24-2013 “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Tomé, Lester, "“Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics" (2013). Dance: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs/5 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Dance: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] POSTPRINT “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Dance Chronicle 36/2 (2013), 218-42 https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792325 This is a postprint. The published article is available in Dance Chronicle, JSTOR and EBSCO. Abstract: Alicia Alonso contended that the musicality of Cuban ballet dancers contributed to a distinctive national style in their performance of European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. A highly developed sense of musicality distinguished Alonso’s own dancing. For the ballerina, this was more than just an element of her individual style: it was an expression of the Cuban cultural environment and a common feature among ballet dancers from the island. In addition to elucidating the physical manifestations of musicality in Alonso’s dancing, this article examines how the ballerina’s frequent references to music in connection to both her individual identity and the Cuban ballet aesthetics fit into a national discourse of self-representation that deems Cubans an exceptionally musical people. -

Preparing Musicians Making New Sound Worlds

PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Compiled by Orlando Musumeci PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Proceedings of the SEMINAR of the COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya – Barcelona – SPAIN 5-9 JULY 2004 Compiled by Orlando Musumeci Published by the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya Catalan texts translated by Mariam Chaib Babou (except for Rosset i Llobet) Spanish texts translated by Orlando Musumeci (except for Estrada, Mauleón and Rosset i Llobet) Copyright © ISME. All rights reserved. Requests for reprints should be sent to: International Society for Music Education ISME International Office P.O. Box 909 Nedlands 6909, WA, Australia T ++61-(0)8-9386 2654 / F ++61-(0)8-9386-2658 [email protected] ISBN: 0-9752063-2-X ISME COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN DIANA BLOM [email protected] University of Western Sydney – AUSTRALIA PHILEMON MANATSA [email protected] Morgan Zintec – ZIMBABWE ORLANDO MUSUMECI (Chair) [email protected] Institute of Education – University of London – UK Universidad de Quilmes – Universidad de Buenos Aires – Conservatorio Alberto Ginastera – ARGENTINA INOK PAEK [email protected] University of Sheffield – UK VIGGO PETTERSEN [email protected] Stavanger University College – NORWAY SUSAN WHARTON CONKLING [email protected] Eastman School of Music – USA GRAHAM BARTLE (Special Advisor) [email protected] -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

Rebranding Initiative

REBRANDING INITIATIVE Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. History and Summary of Issues. 2. Review of Strengths and Weaknesses. 3. Suggested Actions Organized in the Following Categories: a. Board Structure b. Administrative Structure c. Financial d. Choir Structure and Performances e. Marketing 4. Current Mission and Vision Statements Page 2 HISTORY AND SUMMARY OF ISSUES The San Antonio Choral Society began in 1964. It’s original purpose was to provide a community based choir that would be large enough to sing master works and more difficult works than most church choirs could perform. The choir drew members from all over San Antonio (mostly from church choirs) and was an instant success. SACS continued in that mode until the 1990’s when the repertoire was expanded to include more popular music. In 1996, Broadway musicals were added for a “Pops” concert. The choir continued to be managed by a group of charter members until 2013 when a large number of charter members retired from the choir. At that time Jennifer Seighman was hired to be the artistic director for the choir. Jennifer began to raise the standard in terms of music quality, performance arrangement, singer’s skills and music education. Everyone enjoyed the new challenge. In addition, in 2014 the choir was the beneficiary of sizable funds from the estate of a deceased member that continued through 2016. Those funds have now ceased leaving the choir in a quandary as to how to deal with increased costs of operations and no clearly defined revenue source. The loss of funds has caused the officers to reassess our current situation and try to project what direction is needed for the future. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8. -

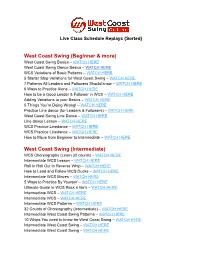

West Coast Swing (Beginner & More)

Live Class Schedule Replays {Sorted} West Coast Swing (Beginner & more) West Coast Swing Basics – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Dance Basics – W ATCH HERE WCS Variations of Basic Patterns – W ATCH HERE 5 Starter Step Variations for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE 7 Patterns All Leaders and Followers Should know – W ATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice Alone – WATCH HERE How to be a Good Leader & Follower in WCS – WATCH HERE Adding Variations to your Basics – W ATCH HERE 5 Things You’re Doing Wrong! – WATCH HERE Practice Line dance (for Leaders & Followers) – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Line Dance – WATCH HERE Line dance Lesson – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE How to Move from Beginner to Intermediate – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing (Intermediate) WCS Choreography (Learn 32 counts) – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Lesson – WATCH HERE Roll In Roll Out to Reverse Whip – WATCH HERE How to Lead and Follow WCS Ducks – W ATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Moves – WATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice By Yourself – WATCH HERE Ultimate Guide to WCS Rock n Go’s – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Patterns – WATCH HERE 32 Counts of Choreography (Intermediate) – W ATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing Patterns – WATCH HERE 10 Whips You need to know for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing ( Advanced) Advanced WCS Moves – WATCH HERE -

Nightclub Two-Step (Club Two-Step, NC2S)

Nightclub Two-Step (Club Two-Step, NC2S) Richard Powers Buddy Schwimmer developed this dance in the late 1970s and it has become widely popular among American social dancers. It is the perfect dance for easygoing, moderate-tempo music, and provides a welcome break between fast dances. It can be danced in a wide range of tempos, from 72 to 92 beats per minute, with 82 bpm as its sweet spot. Buddy Schwimmer originally taught Nightclub Two-Step as rock-step first, danced in quick-quick-slow timing. Today dancers accept both slow-quick-quick or quick-quick-slow timings, depending on what the music indicates. We teach it in the slow-quick-quick timing for two reasons. 1) This timing feels more musical, especially for the Follow role, letting her dance the strongest movements at the strongest moment in the music, on count 1. When the music goes, the Follow goes, instead of being delayed by a rock step. 2) This timing is more commonly done in the Bay Area, and we want our students here to dance comfortably with most local dancers. But we don't dismiss the other timing. They're both good. You'll probably want to adopt the timing done by most dancers in your area. The Basic Step Take a relaxed closed dance position. Count 1 The Lead takes a slow step to the left side with his left foot as the Follow steps side right. 2 The Lead rocks his right foot behind his left heel, taking weight on the ball of his right foot, as the Follow rocks back left. -

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality by Martha Edwards In this article, I’m going to talk about a simple thing that you can do to make you, your band mates, and your dance community fall in love with the music that you make. It’s called phrasing. Yup, phrasing. Musical phrasing is a lot like verbal phrasing. Sentences start somewhere and end somewhere, just like music. Sometimes they start soft, and grow and grow until they END! SOMETIMES they start big and taper off at the end. Sometimes they grow and get BIG and then taper off at the end. But a lot of people never notice that music does the same thing, that it comes from somewhere and goes somewhere. When you help it do that, you’re really sending a musical experience to your audience. Otherwise, you’re just typing. What do I mean by typing? I mean that, if all you do is play the notes, one after another, at the same intensity from beginning to end, you could play the notes perfectly, but your playing would be boring. You wouldn’t be shaping the phrase, you would just be sending out a kind of telegraph message with no emotion attached. I think it happens because playing music is hard, and it’s a big challenge just to be able to play the notes of a tune at all. When you finally get the notes of a tune, one after another, it’s a kind of victory. But don’t stop with just the notes. Learn to play musically! photo of Miranda Arana, Jonathan Jensen and Martha Edwards (courtesy Childgrove Country Dancers, St. -

Advanced Ballet Technique (Majors) -- Daa 4210 Spring 2019

ADVANCED BALLET TECHNIQUE (MAJORS) -- DAA 4210 SPRING 2019 Tuesday/Thursday 8:45 – 10:15 AM G-11, McGuire Pavilion (though we may shift/rotate spaces all semester) INSTRUCTOR OF RECORD: Assistant Professor Elizabeth Johnson [email protected] *Email Policy: Use ONLY your UFL.EDU email account for e-mail correspondence related to class. Please include your name & class in the subject line or within the body of all correspondence. Syllabi are posted at CFA website under: Student & Parents: http://arts.ufl.edu/syllabi/ Lab Fees can be located at: http://registrar.ufl.edu/soc/201608/all/theadanc.htm Office: Room 234, Nadine McGuire Theatre & Dance Pavilion Office Hours: T/TH 10:30 AM – 12:00 PM, F by appointment Office Phone: 352-273-0522 REQUIRED TEXT: Readings from various sources will be provided digitally/free of charge. TBD. RECOMMENDED TEXT: TECHNICAL MANUAL AND DICTIONARY OF CLASSICAL BALLET by Gail Grant CATALOG DESCRIPTION: DAA 4210 Credits: 2; can be repeated with change in content up to 8 credits. Prereq: audition. Advanced ballet technique with discussion of terminology and style. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class will move beyond the intermediate level of ballet technique to address advanced concepts. The language “concepts” indicates that the interweaving of embodied and theoretical material is at an advanced level physically, intellectually, and academically. This includes evidence of understanding in a more sophisticated way the course’s specific somatic lens. Class format will be that of the traditional ballet class including barre, centre, and petit and grand allegro. Readings, video viewings, and a related research assignment are required. -

Improving the ECD Open Band Experience by Robert Reichert, Asheville, NC

Improving the ECD Open Band Experience by Robert Reichert, Asheville, NC op quiz: Why is it easier to put together a successful practice time, open band for a contra dance, than an open band play new tunes forP an English country dance? Because contra dances are at dance tempo not danced to specific tunes — unlike English country with unfamiliar dance. In my opinion, contra dance musicians in an open musicians, is band play the standard contra repertoire known to all the not limited musicians; consequently, a contra open band has only to to this recent come together as an ensemble, without the complexity of experience, and motivated me to write this article. learning new contra tunes. In an open band, familiarity I attended a dance week in Kentucky a few years ago, and with the tunes matters a lot to amateur musicians of the same thing happened at the English open-mic, open various skills who have never played together. band. The open-mic callers were unaware of the difficulties for the musicians of both learning new tunes and playing I recently attended a dance camp that included an evening with unfamiliar musicians. The musicians were asked to of English country dance for open-mic callers and an play all new tunes; very quickly, the open band dwindled open band. That is, the callers and the band members from over twnety musicians to just five. After the few of were amateurs getting together for a single dance, and us remaining musicians insisted that the open-mic dances the band members had never played together. -

Manor Primary School Music Year 1: in the Grove Overview of the Learning: All the Learning Is Focused Around One Song: in the Groove

Manor Primary School Music Year 1: In The Grove Overview of the Learning: All the learning is focused around one song: In The Groove. The material presents an integrated approach to music where games, the interrelated dimensions of music (pulse, rhythm, pitch etc.), singing and playing instruments are all linked. Core Aims Pupils should be taught How to listen to music. perform, listen to, review and evaluate music across a range of historical periods, genres, styles and To sing a range of songs song. traditions, including the works of the great composers and musicians To understand the geographical origin of the music and in which era it was composed. Learn to sing and to use their voices, to create and compose music on their own and with others, To experience and learn how to apply key musical concepts/elements, eg finding a pulse, clapping have the opportunity to learn a musical instrument, use technology appropriately and have the a rhythm, use of pitch. opportunity to progress to the next level of musical excellence To play the accompanying instrumental parts (optional). understand and explore how music is created, produced and communicated, including through the inter-related dimensions: pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure and To work together in a band/ensemble. appropriate musical notations. To develop creativity through improvising and composing within the song. To understand and use the first five notes of C Major scale while improvising and composing. To experience links to other areas of the curriculum To recognise the style of the music and to understand its main style indicators.