The Grassling Claws in the Hair of Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racoon 04-05.3.Pub

1 Periodico di informazione, cultura e curiosità dell’I.S.I.S.S. “Marco Casagrande” Pieve di Soligo Anno 3, Numero 3, 10 marzo 2005 Salute, gente! IL MIO CANTO LIBERO E’ marzo, ormai. A marzo il sole tramonta dopo le sei del pomeriggio, e ciò dovrebbe spingermi ad andare a correre per tonificare il fondoschiena, ma il freschino che ancora persiste mi trattiene dal farlo (che peccato!?). A marzo, esposte nelle vetrine dei negozi, si vedono già le collezioni primavera-estate e guardando l’armadio si desidera con tutto il cuore di potersi liberare da pesanti maglioni e soffocanti sciarpone; sennonché la neve ci ricorda che siamo ancora (uffi puffi!) in inverno! E le temperature ribadiscono il In un mondo che non ci vuole più concetto! il mio canto libero sei tu E così, a marzo, nonostante mi fossi ripromessa di E l'immensità buttare giù con un bel footing per stradine tranquille i si apre intorno a noi chili che hanno nome frittelle, panettone, depressione al di là del limite degli occhi tuoi da ritorno a scuola, eccomi seduta sulla sedia di un Nasce il sentimento nasce in mezzo al pianto tranquillo bar ad ammirare i fiocchi bianchi che e s'innalza altissimo e va scendono a mulinelli, sorseggiando una fumante e vola sulle accuse della gente cioccolata calda ipercalorica (ho rifiutato quella light a tutti i suoi retaggi indifferente perché sarebbe stato ipocrita!!). sorretto da un anelito d'amore di vero amore In un mondo che - Pietre un giorno case Fortunatamente, così come ogni periodo non prigioniero è - ricoperte dalle rose selvatiche -

Robert Frost Notes.Pages

Robert Frost looms as a giant figure on the American literary landscape. By concentrating on the FROST countryside, language and experiences of America, WWW.HOGANNOTES.COM his poetry has done much to establish an American poetic identity. In fact, his wry, countrified, New England narrative voice has often been praised as the quintessential voice of American literature. His determination to weave poetry out of everyday experience distinguishes him from most other poets of his age. His poems are honest, open and autobiographical. It has often been said of Frost that he never really tired of retelling the story of his own life. He was also the undisputed master of poetic forms. Writing in a period dominated by free verse, in a time when poetry seemed to have given up on punctuation and capital letters, Frost insisted that poetry have a definite form, that it be dramatic and that it rely on voice tones to vary the effect of its rhythms. If you are reading the poetry of Robert Frost for the first time, one of the things that should strike you straight away is that his poems are deceptive. What at first appears to be a simple foreword and accessible nature poem will often yield complex, POETRY NOTES LC 20 rich and interesting interpretations. If you would like to read more about Robert Frost’s life, there is a short biography at the back of this booklet. Cian Hogan English Notes 2020 2 75 PAGES 75 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Tuft of Flowers The Tuft of Flowers 4 Commentary 12 I went to turn the grass once after one Mending Wall 16 Who mowed it in the dew before the sun. -

An Exposition of the Book of Ecclesiastes

^f^^ ^^^^ LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF 1 LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF T /v /v r^ (V (V fv TTTTTrjrTmi "7r?^nprrc7 LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ^^ zS^ '-^ F CALIFORNIA LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA % ryrTTTrTrj^E 7r-^i-K~j~nrj: C3 ^i ^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/expositionofbookOObridrich AN EXPOSITION OF THE BOOK OF ECCLESIASTES. BY THS REV. CHARLES^IiroGES, M.A., RECTOR OF IlINTON MARTELL, DORSET. AUIBOR OF AN " EXPOSITION OF I-SALM CXDC ;" " COiDIENTARY OX PROVERBS " CTBISnAN MDOSTRY ;" " MEMOffi OF 31ART JANE GRAHAM," ETC. LI P!OF THB UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK: ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS, No. 580 BROADWAY. 1860. -^^ ^-"i-^d. EDWAED 0, JENKINS, Printer and Stereotyper, No. 26 Feankfobt Stebet. PREFACE. The Book of Ecclesiastes has exercised the Church of God in no common degree. Many learned men have not hesitated to number it among the most diffi- cult Books in the Sacred Canon. ^ Luther doubts Avhether any Exposition up to his time has fully mas- tered it.' The Patristic Commentaries, from Jerome downwards, abound in the wildest fancies ; so that, as one of the old interpreters observes, ' the trifles of their allegories it loathetli and wearieth me to set down." Expositors of a different and later school have too often/' darkened counsel bywords without knowledge" (Job, xxxviii. 2) ; perplexing the reader's mind with doubtful theories, widely diverging from each other. The more difficult the book, the greater the need of Divine Teaching to open its contents. -

You Made 40 Years Possible! in THIS ISSUE This Year, Irvine Turns 40! Here’S a Brief OUR EARLY YEARS Ask the Naturalist

spring 2015 Volume 40, Issue #1 UnderstoryTHE NEWSLETTER OF IRVINE NATURE CENTER 40CELEBRATING years of environmental education Did you know? Irvine has spent four decades inspiring the community to explore, respect and protect nature. You Made 40 Years Possible! IN THIS ISSUE This year, Irvine turns 40! Here’s a brief OUR EARLY YEARS Ask the Naturalist ..................... 3 history of where we’ve come from. A small group of dedicated nature- The Nature Preschool at Irvine .... 4 enthusiasts formed a board and then Animal Spotlight ....................... 5 Look for milestone celebrations all hired its first Executive Director, Volunteer Spotlight ................... 6 year long! “Bud” Ribero. He hailed from the Funder Focus ............................. 7 AT OUR START Massachusetts Audubon Society. During Your Irvine at Work .................. 8 In 1975, sisters Olivia Irvine Dodge and this time, St. Tim’s provided the barns Signs of the Season ................. 10 Clotilde “Coco” Irvine Moles made a rent-free and even paid Irvine’s utilities. Welcome New Members ......... 11 substantial gift to St. Timothy’s School In 1976, Irvine held its first birdseed Spring 2015 Programs ............ 12 in Stevenson, Md., for the express sale, distributing 7 tons from the back Kids...............................................12 purpose of founding a nature center on of a trailer. Irvine also organized the first Youth .............................................13 their campus. Mrs. Dodge had been a Jones Falls Cleanup, partnering with our Families .........................................13 graduate of St. Tim’s, and imagined the longtime friends, the Greenspring Valley Adults ............................................14 nature center in two rustic old barns Garden Club. (This clean-up would near a pond at St. Tim’s. -

Las Vegas 2019

LAS VEGAS 2019 LAS VEGAS SHOW GUIDE AEROSMITH: DEUCES ARE WILD HEADLINER America's all-time top-selling rock ‘n’ roll band is bringing the heat to the Las Vegas Strip with their headlining residency, which will bring guests face to face with America’s Greatest Rock ‘N’ Roll band in one of the most immersive, state-of-the art audio and video technology experiences in Las Vegas. Featuring never-seen-before visuals and audio from Aerosmith recording sessions! SCHEDULE:Performances Apr 6-26, Jun 19-Jul 9. Limited availability, please enquire. VENUE: Park Theater at Park MGM, 3770 S. Las Vegas Blvd. ABSINTHE EVENT Recently named by Las Vegas Weekly as “the #1 greatest show in Las Vegas history”, this provocative but unforgettable variety show delivers that ‘only in Vegas’ experience you came looking for. Absinthe is an intoxicating cocktail of circus, burlesque and vaudeville that The New York Times calls "Cirque du Soleil as channeled through The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” SCHEDULE:Monday – Sunday. VENUE: Spiegeltent at Caesars Palace, 3570 S. Las Vegas Blvd. THE AUSTRALIAN BEE GEES SHOW EVENT It's Saturday Night Fever every night! One of the most successful and adored acts in musical history is recreated on the Las Vegas stage in a 75-minute multi-media concert event. With over 22 years of experience "Jive Talkin'" you will be danced, sang and swept away with hits like, "Staying Alive," "You Should Be Dancing," and "How Deep Is Your Love." SCHEDULE:Saturday – Thursday. Dark Monday. VENUE: Showroom at Excalibur, 3850 S. Las Vegas Blvd. -

The Parable of the Sower, Part 4—The Rocky Ground Hearer” Matthew 13 Dr

L. Matthew in Biblical Perspective The Kingdom of God and the Word of God “The Parable of the Sower, Part 4—The Rocky Ground Hearer” Matthew 13 Dr. Harry L. Reeder III May 24, 2015 – Morning Sermon We will start by looking at Matthew 13. This is the parable of the sower. This is our fourth study of six in this series. Let’s look at Matthew 13. It’s God’s Word and it’s the truth. Matthew 13:1–9, 18–23 says [1] That same day Jesus went out of the house and sat beside the sea. [2] And great crowds gathered about him, so that he got into a boat and sat down. And the whole crowd stood on the beach. [3] And he told them many things in parables, saying: “A sower went out to sow. [4] And as he sowed, some seeds fell along the path, and the birds came and devoured them. [5] Other seeds fell on rocky ground, where they did not have much soil, and immediately they sprang up, since they had no depth of soil, [6] but when the sun rose they were scorched. And since they had no root, they withered away. [7] Other seeds fell among thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked them. [8] Other seeds fell on good soil and produced grain, some a hundredfold, some sixty, some thirty. [9] He who has ears, let him hear.” [18] “Hear then the parable of the sower: [19] When anyone hears the word of the kingdom and does not understand it, the evil one comes and snatches away what has been sown in his heart. -

PD030 Elenco CD Sezione Informatica a Dicembre 2011

SPORTELLO DI PADOVA SEZIONE INFORMATICA Comunicato n. 30 PD - 23/12/2011 INVENTARIO CD MUSICALI A DICEMBRE 2011 n° Autore Titolo Genere 187 Abba The definitive collection Leggera Straniera 112 Abdelli Abdelli Etnico 389 Aboriginal Beats Of Aboriginal Beat from Australia Etnico 481 AC/DS Powerage Rock Straniero 605 Adele 21 Rock Straniero 71 Adiemus Cantata mundi Etnico 417 Aerosmith The very best of Aerosmith Rock Straniero 264 Afrocelt Seed Etnico 488 Afterhours I Milanesi ammazzano il sabato Rock Italiano 314 Alanis Morissette So-Called chaos Rock Straniero 42 Alex Britti It.pop Leggera Italiana 61 Alex De Grassi The water gardon New Age 369 Alice in Chains Live Rock Straniero 307 Alicia Keys The diary of Alicia Keys Rock Straniero 375 Alicia Keys Unplugged Leggera Straniera 608 Alison Krauss & Union Station Paper Airplane Rock Straniero 582 Alva Noto + Ryuichi Sakamoto Summvs Contemporanea 415 Alva Noto Ryuichi Sakamoto Insen Etnico 529 Amadou & Mariam Welcome to Mali Etnico 155 Andrea Bocelli Cieli di Toscana Leggera Italiana 258 Andrea Bocelli Sentimento Leggera Italiana 79 Anggun Chrysalis Rock Straniero 262 Ani Difranco Evolve Rock Straniero 443 Ani Difranco Reprieve Rock Straniero 471 Annie Lennox Song of mass destruction Rock Straniero 514 Annie Lennox Diva Rock Straniero 566 Annie Lennox A Cristmas Cornucopia Rock Straniero 510 Anouar Brahem The astounding eyes of Rita Etnico 604 Anoushka Shankar Traveller Etnico 269 Anovar Braim Le pass du chat noir Etnico 530 Anthony and the Johnsons The crying light Rock Straniero 567 Arcade -

Un Giorno Questo Dolore Ti Sarà Utile” Di Peter Cameron

un film di Roberto Faenza ispirato al romanzo “Un Giorno questo Dolore Ti Sarà Utile” di Peter Cameron con Toby Regbo - Marcia Gay Harden - Peter Gallagher - Lucy Liu Stephen Lang - Deborah Ann Woll e Ellen Burstyn Durata: 98’ Uscita: 24 Febbraio 2012 Distribuzione I MATERIALI STAMPA SONO DISPONIBILI SUL SITO www.01distribution.it, area press www.mymovies.it/ungiorno - fb facebook.com/JeanVigoFilm Ufficio Stampa Film Ufficio Stampa 01 Distribution Giulia Martinez Annalisa Paolicchi [email protected] +39 335 7189949 Cristiana Trotta [email protected] [email protected] RebeccaRoviglioni [email protected] Progetto Scuole: Antonella Montesi +39 349 7767796 n verde 800 96 01 54 [email protected] JEAN VIGO ITALIA e RAI CINEMA Presentano Un film prodotto da Elda Ferri, Milena Canonero e Ron Stein Una produzione Italia-USA Jean Vigo Italia e Four Of A Kind Production In collaborazione con Rai Cinema e The 7th Floor In Associazione con BNL – Gruppo BNP Paribas Vendite estere North American Sales Agent Kevin Iwashina Preferred Content 6363 Wilshire Boulevard suite 350 Los Angeles International Sales Agent Arianne Fraser Highland Film Group 9200 Sunset Blvd. Suite 600 West Hollywood, CA 90069 Office 310-271-8400 Mobile 310-972-9449 CAST ARTISTICO James TOBY REGBO Marjorie MARCIA GAY HARDEN Paul PETER GALLAGHER Rowena LUCY LIU Barry Rogers STEPHEN LANG Gillian DEBORAH ANN WOLL Nanette ELLEN BURSTYN Jeanine Breemer AUBREY PLAZA John GILBERT OWUOR Rhonda DREE HEMINGWAY Henryk Maria OLEK KRUPA Mrs. Breemer SIOBHAN FALLON -

The Extras of Meta-Morphology

The Extras of Meta-Morphology © Copyright, All Rights Reserved: Dr. Andreas Goppold Prof. a.D. & Dr. Phil. & Dipl. Inform. & MSc. Ing. UCSB email: xyz123 (at) mnet-mail de Version: 20191229 The Home Page is: http://www.noologie.de/ A printable .pdf-Version is here: http://www.noologie.de/_extra.pdf The .htm version is here: http://www.noologie.de/_extra.htm This contains all the www-links that can be accessed. Wikipedia: Noology External links: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noology 1 1 Table of Contents: Root Level 1 Table of Contents: Root Level..................................................................................................................3 2 Long Table of Contents.............................................................................................................................4 3 Hyperlinks Referenced...........................................................................................................................11 4 Abbreviations.........................................................................................................................................13 5 The Science of Morphology...................................................................................................................13 6 On Mirror Structures..............................................................................................................................19 7 Words and Morphological Meaning........................................................................................................23 8 -

Global Superstar Mariah Carey Reveals Caution World Tour

GLOBAL SUPERSTAR MARIAH CAREY REVEALS CAUTION WORLD TOUR – Tickets On Sale to the General Public Starting October 26 at LiveNation.com – LOS ANGELES, CA (October 22, 2018) – International singing & songwriting icon Mariah Carey has announced her upcoming Caution World Tour set to kick off in February 2019. The multi-platinum selling, multiple Grammy Award winner will get closer to the fans with her most intimate tour yet. The once-in-a- lifetime 22-city run produced by Live Nation starts in Dallas and will visit Atlanta, Chicago, Toronto, Atlantic City, Philadelphia, and more. Honey B. Fly is the official Mariah Carey fan community. Legacy members of Honey B. Fly will receive first access to tickets starting Tuesday, October 23 at 10:00am local time. Fans may purchase a “Honey B. Fly Live Pass” today, which gives them access not only to ticket presales, but also a free membership to Honey B. Fly, the official Mariah Carey fan community. Fans who are already registered simply need to upgrade their account with the Honey B. Fly Live Pass on MariahCarey.com. Tickets will go on sale to the general public starting Friday, October 26 at LiveNation.com. Citi is the official presale credit card for the Caution World Tour. As such, Citi cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, October 23 at 10:00am local time until Thursday, October 25 at 10:00pm local time through Citi’s Private Pass program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Canadian and U.S. residents who purchase tickets online will be able to redeem one digital or physical copy of her new album and copies must be redeemed by May 6. -

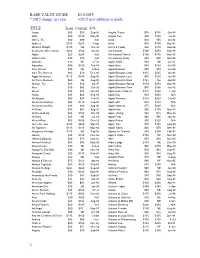

RARE VALUE GUIDE 8/10/2015 * 2015 Change in Value #2015 New Addition to Guide

RARE VALUE GUIDE 8/10/2015 * 2015 change in value #2015 new addition to guide TITLE Issue Current S/O Aaron $45 $50 Sep-00 Angels Prayer $70 $135 Oct-88 Abby $30 $150 May-90 Angels Two $40 $125 Jul-88 ABC’s, The $80 $90 N/A Anita $30 $55 Jun-92 Abilities $100 $200 4-Apr Anna $25 $150 May-92 Abram’s Delight $100 NE Oct-95 Annie & Teddy $20 $110 Sep-86 Across the Silent Snow $200 $300 Jun-95 Anniversary $100 $250 Sep-98 Adam $25 $200 N/A Anniversary Dance $100 $175 May-93 Adam’s Hat $30 $45 N/A Anniversary Song $45 $90 Mar-96 Adorable $75 NE 5-Feb Apple Annie $30 NE Jul-10 Adoration $40 $150 Feb-88 Apple Barn $80 $125 Oct-95 After School $90 NE 2-Sep Apple Baskets $45 $54 Jun-00 After The Harvest $65 $70 Dec-00 Apple Blossom Chat $115 $225 Jun-98 Aggie Memories $115 $140 Sep-98 Apple Blossom Love $80 $150 Jan-96 Air Force Museum $65 NE Aug-98 Apple Blossom Maid $125 NE Apr-00 Airman, The $25 $50 Jul-97 Apple Blossom Spring $150 $250 May-98 Alex $35 $95 Oct-90 Apple Blossom Time $75 $160 Jun-95 Alexis $35 $75 Nov-92 Apple Butter Makers $175 $250 1-Jan Alisha $45 $60 Sep-98 Apple Day $80 $450 N/A All Aboard $50 $85 Feb-90 Apple Farmers $120 $225 Oct-89 All American Boys $65 $110 Feb-88 Apple Girl $30 $150 N/A All American Girls $35 $80 Aug-00 Apple Harvest $75 $225 N/A All Done $35 $60 Aug-95 Apple Kids $60 $175 Mar-87 All Dressed Up $60 $100 Oct-99 Apple Outing $60 $75 May-00 All Ears $45 NE Jul-98 Apple Pals $45 $95 Jan-92 All in a Row $65 $100 Dec-92 Apple Picker $35 $120 N/A All in the Tree $100 $650 Mar-87 Apple Time $70 $145 Aug-90 All -

Musica Italiana Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA ITALIANA AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE 883 Hanno ucciso l'uomo ragno MSI/CD OTT 883 \La \\dura legge del goal! MSI/CD OTT \8*/*/Luciferme Mutazioni MSI/CD LUC 24 GRANA Metaversus MSI/CD VEN 24 GRANA Live MSI/CD VEN 883 Max Pezzali \Gli \\anni MSI/CD OTT 99 Posse Corto circuito MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse \La \\vida que vendrà MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse Cerco tiempo MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse 99 Posse live MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse Incredibile opposizione tour dal vivo 1 MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse Incredibile opposizione tour dal vivo 2 MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse NA_99_10° cd 1 MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse NA_99_10° cd 2 MSI/CD NOV 99 Posse Curre curre guagliò MSI/CD NOV AA.VV. Rubierarumory 2001 MSI/CD RUB AA.VV. Tutto: settembre '96 MSI/CD TUT AA.VV. Matrilineare MSI/CD MAT AA.VV. Demetrio e dintorni. Tributo a Demetrio Stratos MSI/CD DEM AA.VV. Amici di Maria De Filippi: I ragazzi del 2003 MSI/CD AMI AA.VV. \Le \\gocce cadono ma che fa vol. 1 Le canzoni del tempo di guerraMSI/CD GOC AA.VV. Festivalbar 2000, 37° : Compilation rossa MSI/CD FES AA.VV. Festivalbar 2000, 37° : Compilation rossa MSI/CD FES AA.VV. Saranno Famosi MSI/CD SAR AA.VV. Roba di Amilcare MSI/CD ROB AA.VV. \I \\cantautori gli anni d'oro MSI/CD CAN AA.VV. Materiale Resistente MSI/CD MAT AA.VV. Platinum Sanremo MSI/CD PLA AA.VV. Platinum Sanremo MSI/CD PLA AA.VV.