Soldiers in Zimbabwe's Liberation War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Heritage, Bones and Commemoration in Zimbabwe

No 01/2 August 2009 The Politics of the Dead: Living heritage, bones and commemoration in Zimbabwe Joost Fontein, Social Anthropology & Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh Biography Lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Edinburgh, editor of the Journal of Southern African Studies, and co-founder and editor of a new online publication called Critical African Studies. His first monograph, entitled The Silence of Great Zimbabwe: Contested Landscapes and the Power of Heritage (UCL Press), was published in 2006 and he is currently writing a book entitled Water & Graves: Belonging, Sovereignty, and the Political Materiality of Landscape around Lake Mutirikwi in Southern Zimbabwe. Abstract The purpose of this paper is to explore the ambivalent agency of bones as both ‘persons’ and ‘objects’ in the politics of heritage and commemoration in Zimbabwe. It discusses a recent ‘commemorative’ project which has focused on the identification, reburial, ritual cleansing and memorialisation of the human remains of the liberation war dead, within Zimbabwe and across its borders (Mozambique, Zambia, Botswana, Angola and Tanzania). Although clearly related to ZANU PF’s rhetoric of ‘patriotic history’ (Ranger 2004b) that has emerged in the context of Zimbabwe’s continuing political crisis, this recent ‘liberation heritage’ project also sits awkwardly in the middle of the tension between these two related but somehow distinct nationalist projects of the past (heritage and commemoration). Exploring the tensions that both commemorative -

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

Canada Sanctions Zimbabwe

Canadian Sanctions and Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe: Be Very Careful! By Mark Blumberg (January 7, 2009) Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe need to be extremely careful. It is not the place for a new and inexperienced charity to begin foreign operations. In fact, only Canadian charities with substantial experience in difficult international operations should even consider operating in Zimbabwe. It is one of the most difficult countries to carry out charitable operations by virtue of the very difficult political, security, human rights and economic situation and the resultant Canadian and international sanctions. This article will set out some information on the Zimbabwe Sanctions including the full text of the Act and Regulations governing the sanctions. It is not a bad idea when dealing with difficult legal issues to consult knowledgeable legal advisors. Summary On September 4, 2008, the Special Economic Measures (Zimbabwe) Regulations (SOR/2008-248) (the “Regulations”) came into force pursuant to subsections 4(1) to (3) of the Special Economic Measures Act. The Canadian sanctions against Zimbabwe are targeted sanctions dealing with weapons, technical support for weapons, assets of designated persons, and Zimbabwean aircraft landing in Canada. There is no humanitarian exception to these targeted sanctions. There are tremendous practical difficulties working in Zimbabwe and if a Canadian charity decides to continue operating in Zimbabwe it is important that the Canadian charity and its intermediaries (eg. Agents, contractor, partners) avoid providing any benefits, “directly or indirectly”, to a “designated person”. Canadian charities need to undertake rigorous due diligence and risk management to ensure that a “designated person” does not financially benefit from the program. -

Mothers of the Revolution

Mothers of the revolution http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10035 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Mothers of the revolution Author/Creator Staunton, Irene Publisher Baobab Books (Harare) Date 1990 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968.9104 M918 Rights This book is available through Baobab Books, Box 567, Harare, Zimbabwe. Description Mothers of the Revolution tells of the war experiences of thirty Zimbabwean women. Many people suffered and died during Zimbabwe's war of liberation and many accounts of that struggle have already been written. -

From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe.Pdf

THE S.A. ' "!T1!TE OF INTERNATIONAL AFi -! NOT "(C :.-_ .^ FROM RHODESIA TO ZIMBABWE Ah Analysis of the 1980 Elections and an Assessment of the Prospects Martyn Gregory OCCASIONAL. PAPER GELEEIMTHEIOSPUBUKASIE DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE INSTITUUT MN INTERNASIONALE AANGELEENTHEDE THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Martyn Gregory* the author of this report, is a postgraduate research student,at Leicester University in Britain, working on # : thesis, entitled "International Politics of the Conflict in Rhodesia". He recently spent two months in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, : during the pre- and post-election period, as a Research Associate at the University of Rhodesia (now the University of Zimbabwe). He travelled widely throughout the country and interviewed many politicians, officials and military personnel. He also spent two weeks with the South African Institute of International Affairs at Smuts House in Johannesburg. The author would like to thank both, the University of Zimbabwe and the Institute for assistance in the preparation of this report, as well as the British Social Science Research Council which financed his visit to Rhodesia* The Institute wishes to express its appreciation to Martyn Gregory for his co-operation and his willingness to prepare this detailed report on the Zimbabwe elections and their implications for publication by the Institute. It should be noted that any opinions expressed in this report are the responsibility of the author and not of the Institute. FROM RHODESIA TO ZIMBABWE: an analysis of the 1980 elections and an assessment of the prospects Martyn Gregory Contents Introduction .'. Page 1 Paving the way to Lancaster House .... 1 The Ceasefire Arrangement 3 Organization of the Elections (i) Election Machinery 5 (i i) Voting Systems 6 The White Election 6 The Black Election (i) Contesting Parties 7 (ii) Manifestos and the Issues . -

Dealing with the Crisis in Zimbabwe: the Role of Economics, Diplomacy, and Regionalism

SMALL WARS JOURNAL smallwarsjournal.com Dealing with the Crisis in Zimbabwe: The Role of Economics, Diplomacy, and Regionalism Logan Cox and David A. Anderson Introduction Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia) shares a history common to most of Africa: years of colonization by a European power, followed by a war for independence and subsequent autocratic rule by a leader in that fight for independence. Zimbabwe is, however, unique in that it was once the most diverse and promising economy on the continent. In spite of its historical potential, today Zimbabwe ranks third worst in the world in “Indicators of Instability” leading the world in Human Flight, Uneven Development, and Economy, while ranking high in each of the remaining eight categories tracked (see figure below)1. Zimbabwe is experiencing a “brain drain” with the emigration of doctors, engineers, and agricultural experts, the professionals that are crucial to revitalizing the Zimbabwean economy2. If this was not enough, 2008 inflation was running at an annual rate of 231 million percent, with 80% of the population lives below the poverty line.3 Figure 1: Source: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=4350&page=0 1 Foreign Policy, “The Failed States Index 2008”, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=4350&page=0, (accessed August 29, 2008). 2 The Fund for Peace, “Zimbabwe 2007.” The Fund for Peace. http://www.fundforpeace.org/web/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=280&Itemid=432 (accessed September 30, 2008). 3 BBC News, “Zimbabwean bank issues new notes,” British Broadcasting Company. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7642046.stm (accessed October 3, 2008). -

Wfp.Org/Hunger‐Analy�Cs‐Hub)

FOOD SECURITY AND MARKETS MONITORING REPORT April 2021 17 April 2021 Contents Highlights ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Update on the COVID‐19 Situaon ....................................................................................................... 4 Macro‐Economic Situaon ................................................................................................................... 5 Food and Nutrion Security Situaon ................................................................................................... 6 Market Performance Update ............................................................................................................... 8 Food Commodity Prices in Foreign Currency (US$ terms) .............................................................................. 8 Rural markets – review of availability and prices in Zimbabwe dollars (ZWL) ............................................... 9 Urban markets – review of availability and prices in Zimbabwe dollars (ZWL) ............................................ 10 Recommendaons .............................................................................................................................. 11 Annex 1: Markets sample and data collecon……………………………………………………………………………...13 Annex 2: Urban Districts Maize Grain Prices ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Annex 3: Rural Districts Maize Grain Prices ………………………………………………………………………………....13 Annex 4: -

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

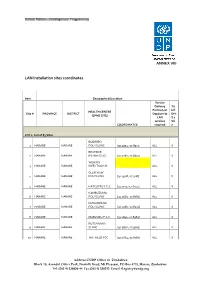

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

Shadow Cultures, Shadow Histories Foreign Military Personnel in Africa 1960–1980

Shadow Cultures, Shadow Histories Foreign Military Personnel in Africa 1960–1980 William Jeffrey Cairns Anderson A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand November 2011 Abstract From the 1960s to the 1980s mercenary soldiers in Africa captured the attention of journalists, authors and scholars. This thesis critically examines the shadows of mercenarism in sub-Saharan Africa during decolonisation – an intense period of political volatility, fragility and violence. The shadows of conflict are spaces fuelled by forces of power where defined boundaries of illegal/legal, illicit/licit and legitimate/illegitimate become obscured. Nordstrom (2000, 2001, 2004, 2007) invokes the shadows as a substantive ethnographic and analytical concept in anthropological research. This thesis considers how the shadows are culturally, socially and politically contingent spaces where concepts of mercenarism are contested. Specific attention is given to ‘shadow agents’ – former foreign military combatants, diplomats and politicians – whose lived experiences shed light on the power, ambiguities and uncertainties of the shadows. Arguing the importance of mixed method ethnography, this thesis incorporates three bodies of anthropological knowledge. Material from the official state archives of New Zealand and the United Kingdom (UK) where, amongst themselves, politicians and diplomats debated the ‘mercenary problem’, are used alongside oral testimonies from former foreign soldiers whose individual stories provide important narratives omitted from official records. This ethnography also draws on multi-sited fieldwork, including participant observation in Africa, the UK and New Zealand that engages with and captures the more intimate details of mercenary soldiering. As findings suggest, the worlds of diplomacy, politics and mercenarism are composed of shadow cultures where new perspectives and understandings emerge. -

Governance and Corruption Parole and Sentencing

Project of the Community Law Centre CSPRI '30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku' April CSPRI '30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku' April 2010 2010 In this Issue: GOVERNANCE AND CORRUPTION PAROLE AND SENTENCING PRISON CONDITIONS SECURITY AND ESCAPES SOUTH AFRICANS IMPRISONED ABOARD OTHER OTHER AFRICAN COUNTRIES Top of GOVERNANCE AND CORRUPTION Page Prisons to increase self sufficiency: The Minister of Correctional Services, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, is reported to be considering returning to the system in which prisoners worked on prison farms to produce food for their own consumption. According to the report, prisoners would produce their own food in future to ease pressure on the budget of the Department of Correctional Services. The department currently pays catering contractors millions of rand per year to run prison kitchens and feed prisoners. The Minister said, under the Correctional Services Act, prisoners are supposed to work but this is uncommon in South African prisons. Reported by Siyabonga Mkhwanazi, 6 April 2010, IOL, at http://www.iol.co.za/index.phpset_id=1&click_id=13&art_id=vn20100406043212436C595118 Top of PAROLE AND SENTENCING Page Court releases sick prisoner on humanitarian grounds: The Bellville Specialised Commercial Crimes Court has converted a six-year prison term of a terminally ill prisoner to one year, IOL reported. Stephen Rosen was sentenced to six years imprisonment after being convicted on 101 counts of fraud involving R1, 86 million. According to the IOL report, Magistrate Amrith Chabillal said "You need to understand that your criminal history goes against you and that it's only on humanitarian grounds that I am ruling in favour of your release from prison". -

Year Ending December 31, 2009 Estimates of Expenditure

ESTIMATES OF EXPENDITURE FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 2009 SUMMARY CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY APPROPRIATIONS 2009 BUDGET ESTIMATES No. Title Page Amount Amount Amount Z$ US$ ZAR I. President and Cabinet 28 416,000 20,800 213,512 II. Parliament of Zimbabwe 28 548,000 27,400 281,261 III. Public Service 28 2,367,937,520 118,396,876 1,215,343,932 IV. Audit 29 320,000 16,000 164,240 V. Finance 29 20,000,000 34,495,061 10,265,000 VI. Justice and Legal Affairs 29 19,990,000 999,500 10,259,868 $2,409,211,520 $153,955,637 R1,236,527,813 DETAILED STATEMENT CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY APPROPRIATIONS I. PRESIDENT $416 000 Salary and allowances 416,000 20,800 213,512 (Section 31A (1) of the Constitution as read with Chapter 2:06) II. PARLIAMENT OF ZIMBABWE $548 000 Salary and allowances 548,000 27,400 281,261 (Section 45 (1) of the Constitution as read with Chapter 2:06) III. PUBLIC SERVICE $2 367 937 520 State Service, Judges and Ministerial and Parliamentary pensions and other benefits 1,233,670,340 61,683,517 633,181,302 (Section 112 of the Constitution (Paragraph 1 (4) of Schedule 6) as read with Chapter 2:02; Chapter 7:08; Chapter 16:01; Chapter 16:06 and S.I. 124 of 1992) Refunds of contributions 300,000 15,000 153,975 (Section 112 of the Constitution (Paragraph 1 (4) of Schedule 6) as read with Chapter 16:06) Commutation of pensions 780,160 39,008 400,417 Awards under Pensions (Supplementary) Acts 131,120 6,556 67,297 (Section 6 of Act No. -

An Analysis of the Chronicle's Coverage of the Gukurahundi Conflict in Zimbabwe Between 1983 and 1986

Representing Conflict: An Analysis of The Chronicle's Coverage of the Gukurahundi conflict in Zimbabwe between 1983 and 1986 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Master of Arts Degree in Journalism and Media Studies Rhodes University By Phillip Santos Supervisor: Professor Lynette Steenveld October 2011 Acknowledgements I am forever in the debt of my very critical, incisive, and insightful supervisor Professor Lynette Steenveld whose encyclopaedic knowledge of social theory, generous advice, and guidance gave me more tban a fair share of epiphanic moments. I certainly would not have made it this far without the love and unstinting support of my dear wife Ellen, and daughter, . Thandiswa. For unparalleled teamwork and dependable friendship, thank you Sharon. My friends Stanley, Jolly, Sthembiso, Ntombomzi and Carolyne, tbank you for all the critical conversations and for keeping me sane throughout those tumultuous moments. I also owe particular debt of gratitude to tbe Journalism Department and UNESCO for enabling my studies at Rhodes University. Abstract This research is premised on the understanding that media texts are discourses and that all discourses are functional, that is, they refer to things, issues and events, in meaningful and goal oriented ways. Nine articles are analysed to explicate the sorts of discourses that were promoted by The Chronicle during the Gukurahundi conflict in Zimbabwe between 1982 and 1986. It is argued that discourses in the news media are shaped by the role(s), the type(s) of journalism assumed by such media, and by the political environment in which the news media operate. The interplay between the ro les, types of journalism practised, and the effect the political environment has on news discourses is assessed within the context of conflictual situations.