REPORTS of CERTAIN EVENTS in LONDON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asimov on Science Fiction

Asimov On Science Fiction Avon Books, 1981. Paperback Table of Contents and Index Table of Contents Essay Titles : I. Science Fiction in General 1. My Own View 2. Extraordinary Voyages 3. The Name of Our Field 4. The Universe of Science Fiction 5. Adventure! II. The Writing of Science Fiction 1. Hints 2. By No Means Vulgar 3. Learning Device 4. It’s A Funny Thing 5. The Mosaic and the Plate Glass 6. The Scientist as Villain 7. The Vocabulary of Science Fiction 8. Try to Write! III. The Predictions of Science Fiction 1. How Easy to See The Future! 2. The Dreams of Science Fiction IV. The History of Science Fiction 1. The Prescientific Universe 2. Science Fiction and Society 3. Science Fiction, 1938 4. How Science Fiction Became Big Business 5. The Boom in Science Fiction 6. Golden Age Ahead 7. Beyond Our Brain 8. The Myth of the Machine 9. Science Fiction From the Soviet Union 10. More Science Fiction From the Soviet Union Isaac Asimov on Science Fiction Visit The Thunder Child at thethunderchild.com V. Science Fiction Writers 1. The First Science Fiction Novel 2. The First Science Fiction Writer 3. The Hole in the Middle 4. The Science Fiction Breakthrough 5. Big, Big, Big 6. The Campbell Touch 7. Reminiscences of Peg 8. Horace 9. The Second Nova 10. Ray Bradbury 11. Arthur C. Clarke 12. The Dean of Science Fiction 13. The Brotherhood of Science Fiction VI Science Fiction Fans 1. Our Conventions 2. The Hugos 3. Anniversaries 4. The Letter Column 5. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

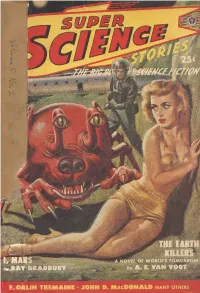

Super Science Stories V05n02 (1949 04) (Slpn)

’yf'Ti'-frj r " J * 7^ i'irT- 'ii M <»44 '' r<*r^£S JQHN D. Macdonald many others ) _ . WE WILL SEND ANY ITEM YOU CHOOSE rOR APPROVAL UNDER OUR MONEY BACK GUARANTEE Ne'^ MO*' Simply Indicate your selection on the coupon be- low and forward it with $ 1 and a brief note giv- ing your age, occupotion, and a few other facts about yourself. We will open an account for ycu and send your selection to you subject to your examination, tf completely satisfied, pay the Ex- pressman the required Down Payment and the balance In easy monthly payments. Otherwise, re- turn your selection and your $1 will be refunded. A30VC112 07,50 A408/C331 $125 3 Diamond Engagement 7 Dtomond Engagement^ Ring, matching ‘5 Diamond Ring, matching 8, Dior/tond Wedding Band. 14K yellow Wedding 5wd. 14K y<dlow or IBK white Gold. Send or I8K white Cold, fiend $1, poy 7.75 after ex- $1, pay .11.50 after ex- amination, 8.75 a month. aminatioii, 12.50 a month. ^ D404 $75 Man's Twin Ring with 2 Diamonds, pear-shaped sim- ulated Ruby. 14K yellow Gold. Send $1, pay 6.50 after examination, 7.50 a month* $i with coupon — pay balance op ""Tend [ DOWN PAYMENT AFTER EXAMINATION. I, ''All Prices thciude ''S T'" ^ ^ f<^erat fox ", 1. W. Sweet, 25 West 1 4th St. ( Dept. PI 7 New York 1 1, N, Y. Enclosed find $1 deposit. Solid me No. , , i., Price $ - After examination, I ogree to pay $ - - and required balance monthly thereafter until full price . -

A Ficção Científica De Acordo Com Os Futurians Science Fiction According

A ficção científica de acordo com os Futurians Science Fiction According to the Futurians Andreya Susane Seiffert1 DOI: 10.19177/memorare.v8e12021204-216 Resumo: The Futurian Society of New York, ou simplesmente The Futurians, foi um grupo de fãs e posteriormente escritores e editores de ficção científica, que existiu de 1938 a 1945. O período é geralmente lembrado pela atuação do editor John Cambpell Jr. à frente da Astounding Science Fiction. A revista era, de fato, a principal pulp à época e moldou muito do que se entende por ficção científica até hoje. Os Futurians eram, de certa forma, uma oposição a Campbell e seu projeto. Três membros do grupo viraram editores também e foram responsáveis por seis revistas pulps diferentes, em que foram publicadas dezenas de histórias com autoria dos Futurians. Esse artigo analisa parte desse material e procura fazer um pequeno panorama de como os Futurians pensaram e praticaram a ficção científica no início da década de 1940. Palavras-chave: Ficção Científica. Futurians. Abstract: The Futurian Society of New York, or simply The Futurians, was a group of fans and later writers and editors of science fiction, which existed from 1938 to 1945. The period is generally remembered for the role of editor John Cambpell Jr. at the head of Astounding Science Fiction. The magazine was, in fact, the main pulp at the time and shaped much of what is understood by science fiction until today. The Futurians were, in a way, an opposition to Campbell and his project. Three members of the group became editors as well and were responsible for six different pulp magazines, in which dozens of stories were published by the Futurians. -

Checklist of Fantasy Magazines 1945

A CHECKLIST OF FANTASY MAGAZINES 1945 Edition Bulletin Number One 20 c to Subscribers PREFACE As the first of a long line of Foundation publications we are happy to present a relatively complete checklist of all fantasy periodicals. Insofar as the major Eng lish-language titles are concerned, we believe this list to be both complete and error-free, but it was not poss ible to furnish an adequate listing of.several of the more obscure items. It is also very likely that there exist several foreign language publications whose names are not even known to us. Anyone able to furnish addi tional information is requested to send it to Forrest J. Ackerman, 236^ N. New Hampshire, Los Angeles 4, Cal., for inclusion in the next edition of this checklist. No author is shown on the title page of this pamphlet because in its present form it is the work of at least five individuals: Norman V. Lamb, William H. Evans, Merlin W. Brown, Forrest J. Ackerman, and Francis T, Laney. The Fantasy Foundation wishes to extend its thanks to these gentlemen, as well as to the several members of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society who assisted in its production. THE FANTASY FOUNDATION June 1, 1946 Copyrighted. 1946 The Fantasy Foundation AIR WONDER STORIES (see WONDER) AMAZING STORIES (cont) 1929 (cont) AMAZING detective tales Vol. 4, No. 1 — April —0O0— Arthur H. Lynch, Ed. Hugo Gernsback, Ed. Vol. 4, No. 2 — May 1930 3 — June Vol. 1 No. 6 -- June 4 — July 7 — July 5 -- August 8 — August 6 — September 9 — September 7 — October 10 — October T. -

Eng 4936 Syllabus

ENG 4936 (Honors Seminar): Reading Science Fiction: The Pulps Professor Terry Harpold Spring 2019, Section 7449 Time: MWF, per. 5 (11:45 AM–12:35 PM) Location: Little Hall (LIT) 0117 office hours: M, 4–6 PM & by appt. (TUR 4105) email: [email protected] home page for Terry Harpold: http://users.clas.ufl.edu/tharpold/ e-Learning (Canvas) site for ENG 4936 (registered students only): http://elearning.ufl.edu Course description The “pulps” were illustrated fiction magazines published between the late 1890s and the late 1950s. Named for the inexpensive wood pulp paper on which they were printed, they varied widely as to genre, including aviation fiction, fantasy, horror and weird fiction, detective and crime fiction, railroad fiction, romance, science fiction, sports stories, war fiction, and western fiction. In the pulps’ heyday a bookshop or newsstand might offer dozens of different magazines on these subjects, often from the same publishers and featuring work by the same writers, with lurid, striking cover and interior art by the same artists. The magazines are, moreover, chock-full of period advertising targeted at an emerging readership, mostly – but not exclusively – male and subject to predictable The first issue of Amazing Stories, April 1926. Editor Hugo Gernsback worries and aspirations during the Depression and Pre- promises “a new sort of magazine,” WWII eras. (“Be a Radio Expert! Many Make $30 $50 $75 featuring the new genre of a Week!” “Get into Aviation by Training at Home!” “scientifiction.” “Listerine Ends Husband’s Dandruff in 3 Weeks!” “I’ll Prove that YOU, too, can be a NEW MAN! – Charles Atlas.”) The business end of the pulps was notoriously inconstant and sometimes shady; magazines came into and went out of publication with little fanfare; they often changed genres or titles without advance notice. -

Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2006 0749: Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the Fiction Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006, Accession No. 2006/04.0749, Special Collections Department, Marshall University, Huntington, WV. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Search Our Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Manuscript Collections by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 0 REGISTER OF THE NELSON SLADE BOND COLLECTION Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2007 1 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, WV 25755-2060 Finding Aid for the Nelson Slade Bond Collection, ca.1920-2006 Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Processor: Gabe McKee Date Completed: February 2008 Location: Special Collections Department, Morrow Library, Room 217 and Nelson Bond Room Corporate Name: N/A Date: ca.1920-2006, bulk of content: 1935-1965 Extent: 54 linear ft. System of Arrangement: File arrangement is the original order imposed by Nelson Bond with small variations noted in the finding aid. The collection was a gift from Nelson S. Bond and his family in April of 2006 with other materials forwarded in May, September, and November of 2007. -

Futuria 2 Wollheim-E 1944-06

-—- J K Th-1 Official Organ.?f the Futu- . _ r1an Socle tv of Few York - - /tj-s 1 Num 2 Elsie Balter Wollhelm -Ed. w "kxkkxkkkkkx-xkk xkkxkkwk-kk-xwk^kk**#**kk-if*Wkkk*kk#k*«**-ft-»<■*■**"■*■* #****'M'**'it F'jlUr.IA Is an occasional publication, which should appear no less fre quently than once every three years, for the purpose op keeping various persons connected with' the science-fiction and fantasy fan movememts a mused and. lnfr*rnre?d, along with the Executive Committee of the Society, who dedlcat'e the second Issues of the W'g official organ, to fond mem ories of the ISA. .. -/("■a- xkk k'xk x x-kxxxkk-xxkkk-xxx kwk kk it- y't-i'r x-xkkkkkk-xkxxkk xkkkxkk-k k-xkkkkwxk k-kkkk '* k-xkkkii- xkkkkkwkkkk kkkkkkkkkkkk-k kkkkkkk kk kk ii-ifr-14-"X-«<"»*■ ■»«■-ifr kkxkxk-x it- k x kkkkkkHt-k ><*** Executive Committee -- Futurlen Society of Nev/ York John B. Michel - - Director . Robert W. Lowndes, Secretarv Elsie Balter Wollhelm, Editor Donald A. Wollhoim, Treasurer Chet Cohen, Member-At-Large ■x-xxk-lt-xkk-x-x-xk-x xxk-xwk-kk-xk-xx x-x -Xk k'k kxkk-xkkkk’x-xkxk k -xkkkxkkkkkkkk-xkkkkkkkkk " ”x xkx-X x-x-x-x kxx w-frjf xx-kkx kk-x i4w xx-xk* xk x x x-x kk x-x-x -x-k kk kkxkkkk -xkkkkkkkkk-xkkkkkkkk Futurlen Society o.f. New York -- Membership List act!ve members Honor Roll..:, Members Lp Service. John B. Michel Fre.deri.k Pohl Donald A, Wellheim Richard Wilson Robert W. -

Sam Moskowitz a Bibliography and Guide

Sam Moskowitz A Bibliography and Guide Compiled by Hal W. Hall Sam Moskowitz A Bibliography and Guide Compiled by Hal W. Hall With the assistance of Alistair Durie Profile by Jon D. Swartz, Ph. D. College Station, TX October 2017 ii Online Edition October 2017 A limited number of contributor's copies were printed and distributed in August 2017. This online edition is the final version, updated with some additional entries, for a total of 1489 items by or about Sam Moskowitz. Copyright © 2017 Halbert W. Hall iii Sam Moskowitz at MidAmericon in 1976. iv Acknowledgements The sketch of Sam Moskowitz on the cover is by Frank R. Paul, and is used with the permission of the Frank R. Paul Estate, William F. Engle, Administrator. The interior photograph of Sam Moskowitz is used with the permission of the photographer, Dave Truesdale. A special "Thank you" for the permission to reproduce the art and photograph in this bibliography. Thanks to Jon D. Swartz, Ph. D. for his profile of Sam Moskowitz. Few bibliographies are created without the help of many hands. In particular, finding or confirming many of the fanzine writings of Moskowitz depended on the gracious assistance of a number of people. The following individuals went above and beyond in providing information: Alistair Durie, for details and scans of over fifty of the most elusive items, and going above and beyond in help and encouragement. Sam McDonald, for a lengthy list of confirmed and possible Moskowitz items, and for copies of rare articles. Christopher M. O'Brien, for over 15 unknown items John Purcell, for connecting me with members of the Corflu set. -

FANI TASY I\EVI Ivv Yol

FANI TASY i\EVI Ivv Yol. f, No. tl SIXPENCE AUG.-SEP. 1947 AN END TO BANALITY It's Curtains for Space Opera FROM FORREST J. ACIiI'R]TTAN Jull' and August issues of Writer's Digest l eatured ariicles by Margaret St. Clair, science nction wrirel', sulvey- ing the f,eld from the viewpoint oI the newcomet' who rvants io bleak lnto it and detailing tlle individua] requirements of the magazines. The second article gives namcs and addresses ol lan clubs and therl pul-llications, so that rvri;els may "catch the spirit of what reader's rvanl and get the mood of the fan scated in his orvu armchair." The July articlc adf ised nerv authors to pa}- llalticular atlention to f an letters in the magazines. 'T'he typicai science fic.ioD ian is ]'oung, male (though there ale some de- voted feninine ones), literate, quite iutelligent. ir-iterested in ideas. His mental horizon is broader tlxan that of the average cil,izen. He is strorrgll' arvare of what his likes and dislikes are, and the rvriter $'ho succeeds in pleasing him will hear of il. In my belief thc science fi.ctioi1 fan is a def,niteh' supelior type, but I ma1. be prejudiced." Dealing r',.ith cunent trends in the medium. i\,Irs. St. Clail sa]'s: "Ccrtairrly the present trend is dead e\\'al.' ilom the aptl}*-named 'space opera.' Blood and thund-er is more or lcss on its rval' out, ihough I suppose we shall never get rid of it c'rtilely . -

Os Futurians E a Produção Da Ficção Científica Nos Estados Unidos Da Década De 1940

OS FUTURIANS E A PRODUÇÃO DA FICÇÃO CIENTÍFICA NOS ESTADOS UNIDOS DA DÉCADA DE 1940 Andreya S. Seiffert1 Resumo: No presente trabalho, eu discuto a participação dos futurians no mercado editorial de pulps do começo dos anos quarenta. The Futurian Society of New York, ou simplesmente The Futurians, foi um fandom americano que existiu de 1938 a 1945. Fizeram parte do grupo vários nomes importantes para a ficção científica nos anos seguintes, como Donald Wollheim, Frederik Pohl, Isaac Asimov, Damon Knight e Judith Merril. No início da década de 1940, os futurians começaram a ter um papel importante no cenário da ficção científica profissional, tanto publicando histórias quanto editando as revistas pulp. Ao todo, eles controlaram seis publicações diferentes, onde publicaram dezenas de histórias, algumas das quais eu analiso brevemente. Além das histórias, discuto também os editoriais, a seção de cartas dos leitores e as ilustrações, e procuro mostrar como a ficção científica era pensada e construída de forma coletiva pelos futurians, e como suas contribuições foram inovadoras para o gênero que se desenvolvia. Palavras-chave: futurians; ficção científica; pulps. As revistas literárias impressas em papel barato (woodpulp) se disseminaram nos Estados Unidos nas primeiras décadas do século XX. Estima-se que em meados da década de 1930, 30 a 40% da população letrada lia revistas pulp nos Estados Unidos (CHENG, 2012). Geralmente cada título explorava um tema, como histórias de faroeste, de detetive ou de amor. Em 1926, Hugo Gernback criou a Amazing Stories, uma pulp exclusiva para o que ele chamou de “scientifiction” e que mais tarde passou a ser chamada de science fiction, ou ficção científica. -

Early Asimov © 1972 by Isaac Asimov © 1978 Editorial Bruguera Edición Digital De Umbriel R6 10/02 En Memoria De John W

EEAARRLLYY AASSIIMMOOVV IIssaaaacc AAssiimmoovv Isaac Asimov Título original: The early Asimov © 1972 by Isaac Asimov © 1978 Editorial Bruguera Edición digital de Umbriel R6 10/02 En memoria de John W. Campbell Jr. (1910-71), por razones que esta obra revelará ampliamente. Índice Introducción Tendencias (Trends; 1939) Un arma demasiado terrible para emplear (The weapon too dreadful to use; 1939). La amenaza de Calixto (The Callistan menace; 1940). Un anillo alrededor del sol (Ring around the Sun; 1940). La magnífica posesión (The magnificent possession; 1940). Mestizo (Half-Breed; 1940) El sentido secreto (The secret sense; 1941). Fraile negro de la llama (Black friar of the flame; 1942). Navidad en Ganímedes (Christmas on Ganymede; 1942) Mestizos en Venus (Half-Breeds on Venus; 1940) Herencia (Heredity; 1941) Historia (History; 1941) Homo Sol (Homo sol; 1940) Ritos legales (Legal Rites; 1950.- como James MacCreigh) No definitivo! (Not Final!; 1941) Super-Neutron (Super-neutron; 1941) La novatada (The Hazing; 1942) El numero imaginario (The Imaginary; 1942) El hombrecillo del metro (The Little Man on the Subway; 1950) Cronogato (Time Pussy; 1942) ¡Autor! ¡Autor! (Author! Author!; 1964) Sentencia de muerte (Death Sentence;1943) Callejón sin salida (Blind Alley; 1945) ¡No hay relación! (No Connection;1948) Las propiedades endocrónicas de la tiotimolina re-sublimada (The Endochronic Properties of Resublimated Thiotimoline;1948) La carrera de la reina encarnada (The Red Queen's Race;1949) Madre Tierra (Mother Earth; 1949) INTRODUCCIÓN Aunque he escrito más de ciento veinte libros, sobre casi todos los temas, desde astronomía a Shakespeare y desde matemáticas a sátira, se me conoce sobre todo como autor de ciencia-ficción.