The Law of Parks and Protected Areas in Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kakwa Wildland Park

Alberta Parks Kakwa Wildland Park ...Rocky ridges and sparkling waters Kakwa Wildland Park is a remote, facilities including fire pits, picnic numerous unnamed peaks and ridges rugged place of incredible beauty tables, privies and potable water. in the park as well. with tree-carpeted valleys, swift clear creeks and high mountain ridges. The Kilometre 149: Kakwa Falls, Alberta’s tallest waterfall, park was established in 1996 and is Lick Creek – only 4-wheel drive is a spectacular 30 metres high. Other approximately 650 square kilometres vehicles are suitable on the un- falls in the park include Lower Kakwa in size. maintained trail from here to Falls, located east of the main falls; Kakwa Falls; there are creek and Francis Peak Creek Falls, over Location/Access crossings and wet areas along this which there’s a natural bridge. Kakwa Wildland Park is 160 kilometres route. southwest of Grande Prairie. For There is evidence of glacial outwash travel beyond Lick Creek (roughly 10 Kilometre 160: in the park’s numerous emerald- kilometres from the park’s northern Kakwa Wildland Park boundary. coloured kettle lakes. The lower boundary) a four-wheel drive vehicle is valleys are forested with lodgepole essential. Visitors should check ahead Kilometre 164: pine and there’s subalpine fir at higher with Alberta Parks in Grande Prairie to Deadhorse Meadows equestrian elevations. Three-hundred-year-old confirm road conditions. staging area. Englemann spruce grow in some of the park’s high southern valleys and Kilometre 0: Kilometre 168: large stands of krummholz (stunted Grande Prairie – go south on Hwy. Kakwa day use area and Kakwa subalpine fir growing at tree line) occur 40 then west on Hwy. -

88 Reasons to Love Alberta Parks

88 Reasons to Love Alberta Parks 1. Explore the night sky! Head to Miquelon Lake Provincial Park to get lost among the stars in the Beaver Hills Dark Sky Preserve. 2. Experience Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area in the Beaver Hills UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. This unique 1600 square km reserve has natural habitats that support abundant wildlife, alongside agriculture and industry, on the doorstep of the major urban area of Edmonton. 3. Paddle the Red Deer River through the otherworldly shaped cliffs and badlands of Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park. 4. Wildlife viewing. Our parks are home to many wildlife species. We encourage you to actively discover, explore and experience nature and wildlife safely and respectfully. 5. Vibrant autumn colours paint our protected landscapes in the fall. Feel the crunch of fallen leaves underfoot and inhale the crisp woodland scented air on trails in many provincial parks and recreation areas. 6. Sunsets illuminating wetlands and lakes throughout our provincial parks system, like this one in Pierre Grey’s Lakes Provincial Park. 7. Meet passionate and dedicated Alberta Parks staff in a visitor center, around the campground, or out on the trails. Their enthusiasm and knowledge of our natural world combines adventure with learning to add value to your parks experiences!. 8. Get out in the crisp winter air in Cypress Hills Provincial Park where you can explore on snowshoe, cross-country ski or skating trails, or for those with a need for speed, try out the luge. 9. Devonshire Beach: the natural white sand beach at Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Park is consistently ranked as one of the top beaches in Canada! 10. -

S:\CLERK\JOURNALS\Journals Archive\Journals 1997

JOURNALS FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATURE OF THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA 1997 PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY HON. KEN KOWALSKI, SPEAKER VOLUME CV JOURNALS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATURE __________ FROM APRIL 14, 1997 TO JANUARY 26, 1998 (BOTH DATES INCLUSIVE) IN THE FORTY-SIXTH YEAR OF THE REIGN OF OUR MOST SOVEREIGN LADY HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II BEING THE FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA __________ SITTINGS APRIL 14, 1997 TO JUNE 16, 1997 DECEMBER 8, 1997 TO DECEMBER 10, 1997 __________ 1997 __________ PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY HON. KEN KOWALSKI, SPEAKER VOLUME CV Title: 24th Legislature, 1st Session Journals (1997) SPRING SITTING APRIL 14, 1997 TO JUNE 16, 1997 JOURNALS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA FIRST SESSION TWENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATURE Monday, April 14, 1997 This being the first Day of the First Session of the Twenty-Fourth Legislative Assembly of the Province of Alberta, for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation of His Honour the Honourable H.A. "Bud" Olson, Lieutenant Governor, dated the first day of April in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and ninety-seven; The Clerk of the Legislative Assembly read the Proclamation as follows: [GREAT SEAL] CANADA H.A. "BUD" OLSON, PROVINCE OF ALBERTA Lieutenant Governor. ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom, Canada, and Her Other Realms and Territories, QUEEN, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith PROCLAMATION TO OUR FAITHFUL, the MEMBERS elected to serve in the Legislative Assembly of Our Province of Alberta and to each and every one of you, GREETING.. -

2016 Newsletter

Willmore Wilderness Foundation ... a registered charitable foundation 2016 Annual Newsletter Photo by Susan Feddema-Leonard - July 2015 Ali Klassen & Payton Hallock on the top of Mt. Stearn Willmore Wilderness Foundation Page 2 Page 3 Annual Edition - 2016 Jw Mountain Metis otipemisiwak - freemen President’s Report by Bazil Leonard Buy DVDs On LinePeople & Peaks People & Peaks Ancestors Calling Ancestors CallingLong Road Home Long Road Home Centennial Commemoration of Jasper’s Mountain Métis In 1806 Métis guide Jacco Findlay was the first to blaze a packtrail over Howse Pass and the Continental Divide. He made a map for Canadian explorer David Thompson, who followed one year later. Jacco left the North West Company and became one of the first “Freemen” or “Otipemisiwak” in the Athabasca Valley. Long Road Home: 45:13 min - $20.00 In 1907 the Canadian Government passed an Order in Council for the creation of the Ancestors Calling I thought that I would share a campsites, dangerous river fords, and “Jasper Forest Park”—enforcing the evacuation of the Métis in the Athabasca Valley. By 1909 guns were seized causing the community to surrender its homeland--including Jacco’s descendants. Six Métis families made their exodus after inhabiting the area for a century. Ancestors Calling This documentary, In 1804, the North West Company brought voyageurs, proprietors, evicted families, as well as Jacco’s progeny. Stories are shared through the voices of family recap of 2015, which was a year of historic areas on the west side of the members as they revealLong their Road struggle Home to preserve traditions and culture as Mountain Métis. -

Willmore Wilderness Newsletter

Willmore Wilderness Newsletter Youth Venture into Willmore We want to recognize this year’s who accompanied Zarina and her mom. Emy who both started ‘wildies’ that were youngest traveler in Willmore. Jaely Continuing on in the youth theme, running free in the mountains. Angeen Moberly (age two weeks) was the smallest pictured above are youth who hiked to also started a frisky four-year-old mare Willmore trail hand, and she traveled to Kvass Flats Camp with their moms for a in the Larry Nelles Clinic. Our hats go Kvass Flats Camp on two occasions. A three-day camping trip in August. From off to these three ladies. The Willmore close second in the youngest category is left to right are travelers Payton with Wilderness Foundation sponsored these five-week old Payden who went to Corral mom Jaeda Feddema, also holding Jaely young women along with many other Creek Camp with big sister Brooklyn on their second trip. The lovely Rowan youth at the colt starting clinic. and his parents, Joey Landry and Tyler is eating a cookie with her mom Kim Jenn, Angeen and Emy spent McMahon. The third youngest goes out Teneyck also holding son Julien, with son extensive time in Willmore Park this to six-month old Zarina who traveled Kahleb to the right. summer and fall riding their colts. to Kvass Flats with her mother Becky Pictured (from left to right) above are These three young ladies were filmed Leonard. Special mention goes out to Jenn Houlihan, Angeen Hallock and Emy during the clinic for the movie “Wildie” three-year-old Zachary and one-year-old Hallock. -

Recycling Issues Explored

September 10, 2007 Recycling Issues Explored Edmonton... Having received over 100 written submissions on the Beverage Container Recycling Regulation, the Legislative Assembly’s all-party Standing Committee on Resources and Environment has scheduled public hearings in both Edmonton and Calgary. “Recycling is an issue that affects all Albertans,” said Denis Ducharme, MLA for Bonnyville-Cold Lake and Chair of the Standing Committee on Resources and Environment. “People have a lot to say about the issues, and we want to hear about it.” The public hearing in Edmonton is scheduled to take place at the Legislature Annex (4th Floor, 9718 - 107 Street) on September 18 beginning at 9:30 a.m. In Calgary the hearing is scheduled to take place at the Carriage House Inn (9030 MacLeod Trail South) on September 20 beginning at 1 p.m. People are asked to contact the Committee Clerk before the end of the day on September 12 if they wish to make a presentation. The length of the hearings will be determined by the number of scheduled presentations. The Standing Committee on Resources and Environment is one of four all-party committees established by the Assembly this spring. Among other responsibilities this 11-Member committee is holding public hearings into issues surrounding the Beverage Container Recycling Regulation. These issues include Beverage Container Collection System Is the number of existing bottle depots in Alberta sufficient? Should additional collection options be considered? Exemption of Milk Containers Should milk containers be included in the deposit refund system? Deposit Levels Should the existing deposit levels be raised? Should there be only one deposit level for all containers? Should large or oversize containers (i.e. -

Recommendations of the Standing Committee on Resources and Environment Following Its Deliberations on the Beverage Container Recycling Regulation

Standing Committee on Twenty-Sixth Legislature Third Session StandingResources Committee and Environment on NOVEMBER 2007 Government Services Recommendations upon Review of Key Issues Pertaining to the Beverage Container Recycling Regulation COMMITTEES OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Standing Committee on Resources and Environment 801 Legislature Annex Edmonton, AB T5K 1E4 (780) 644-8621 [email protected] November, 2007 To the Honourable Ken Kowalski Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta The Standing Committee on Resources and Environment has the honour to submit its report and recommendations on issues concerning the Beverage Container Recycling Regulation to the Legislative Assembly of Alberta. Denis Ducharme, MLA Bonnyville-Cold Lake Chair Standing Committee on Resources and Environment Dr. David Swann, MLA Calgary-Mountain View Deputy Chair Standing Committee on Resources and Environment Contents Members, Standing Committee on Resources and Environment 1 1.0 Introduction 2 Executive Summary – Recommendations 3 2.0 Operation and Management of the Beverage Container System 2.1 The Issue 4 2.2 Public Consultation 4 2.3 Recommendations 6 2.4 Rationale 7 3.0 Exemption of Milk Containers 3.1 The Issue 8 3.2 Public Consultation 9 3.3 Recommendations 9 3.4 Rationale 9 Appendix A: List of Presenters 10 MEMBERS OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT 26th Legislature, Third Session Denis Ducharme, MLA Chair Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Dr. David Swann, MLA Deputy Chair Calgary-Mountain View (L) Pearl Calahasen, -

Beyond Banff: Changing Perspectives on the Conservation Mandate on Alberta's East Slopes

BEYOND BANFF: CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON THE CONSERVATION MANDATE ON ALBERTA’S EAST SLOPES John Kristensen Retired Assistant Deputy Minister Alberta Parks 23324 Township Road 515 Sherwood Park, Alberta T8B 1L1 Phone: 780-467-1432 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Since the late 1700s and early 1880s, people have marveled at the breathtaking landscapes and the amazing array of flora and fauna in the Rocky Mountains and foothills of the Eastern Slopes. These natural values have put the Eastern Slopes on the world map as a place to visit and experience the wilderness. Since the early 1900s, government documents have been clear that watershed protection is the highest priority for this area. The Eastern Slopes include an abundance of natural resources: water, fish, wildlife, forests, other vegetation, rangeland, natural gas, oil, coal and other minerals. These natural resources are all in demand to various extents by the public, the private sector and governments. Pressures associated with the gas, oil and forestry industries within the Eastern Slopes have caused significant land use conflicts among the many stakeholders, as they have attempted to balance industrial development with public recreation, a growing tourism sector and conservation of the area’s rich natural resources through multiple land use strategies. Some of the successes and failures are discussed, and recommendations are presented to enhance the ecosystem-based Integrated Resource Management of the area, where conservation principles are respected. 1 BEYOND BANFF: CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON THE CONSERVATION MANDATE ON ALBERTA’S EAST SLOPES John Kristensen Introduction: When I was invited to present a paper on this topic, I accepted because my family and I have camped, hiked, fished and photographed many parts of Alberta’s Eastern Slopes since 1960; and, I had the profound pleasure and honour to work in the Alberta Parks and Protected Areas Division and see first hand the successes and challenges in conserving the Eastern Slopes. -

Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation

Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation E488 Van Vliet Centre http://www.physedandrec.ualberta.ca/ Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2H9 [email protected] Dear Willmore Wilderness Park Visitor! Exploring the Human Dimension: Visitor Use Analysis of Willmore Wilderness Park is a project being conducted by the University of Alberta with support from the Foothills Research Institute and Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation. We are interested in learning more about you and your trip into Willmore. As part of this project, we are conducting Willmore Wilderness Park user surveys, determining user numbers through trail cameras, mapping user patterns through GPS Tracksticks, and conducting interviews with selected individuals. This information is critical to learn as it will help ensure that your Willmore trip experience is being maintained and improved in ways which will greatly benefit you – the Willmore Wilderness Park visitor! The data will also be incorporated into my thesis, part of my Master’s degree requirements at the University of Alberta. We request that one member from your group complete this survey as you enter or exit the park. This includes ALL users regardless of where you are from or what activity you are doing. e.g., locals, non-locals, commercial trail operators, mountain bikers, hikers, outfitters etc.). Please fill out a survey each time you visit Willmore for both day use or overnight use. During this study, you may be offered a GPS Trackstick to use during your Willmore trip. The GPS Trackstick is a small GPS unit that would collect location data about your movement through the park. The unit would be attached for example, to your backpack or saddlebag while you are travelling. -

Management of a River Recreation Resource: Understanding the Inputs To

Management of a River Recreation Resource: Understanding the Inputs to Management of Outdoor Recreational Resources by Kimberley Rae A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Recreation and Leisure Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2007 © Kimberley Rae, 2007 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that a copy of my thesis may be made available electronically to the public. ii Abstract Research into the use of natural resources and protected areas for the pursuit of outdoor recreational opportunities has been examined by a number of researchers. One activity with growth in recent years is river recreation, the use of rivers for rafting, kayaking, canoeing and instructional purposes. These many uses involve different groups of individuals, creating management complexity. Understanding the various inputs is critical for effective management The Lower Kananaskis River, located in Kananaskis Country in Southwestern Alberta, was area chosen to develop an understanding the inputs necessary for effective management. Specifically, this study explored the recreational use of the river in an effort to create recommendations on how to more effectively manage use of the Lower Kananaskis River and associated day-use facilities in the future. Kananaskis Country is a 4,250 km2 multi-use recreation area located in the Canadian Rocky Mountains on the western border of Alberta. Since its designation, the purpose of the area, has been to protect the natural features of the area while providing quality facilities that would complement recreational opportunities available in the area. -

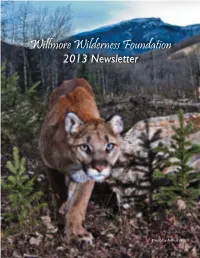

2013 Newsletter

Willmore Wilderness Foundation 2013 Newsletter Photo by Arthur Veitch Willmore Wilderness Foundation Page 2 Page 3 Annual Edition - 2013 2012 Grizzly Bear Survey President’s Report Alberta Bowhunters Hi Everyone: Rockies Tourism Alliance (ANRTA), which is forming a not-for-profit society. Association There were many changes this ANRTA is looking to develop a regional past year, and the Foundation turned marketing strategy. Alberta Fish & Game a milestone in December 2012, Association celebrating its 10th anniversary. The Foundation has also been busy Many exciting developments included in the film production end of things, Alberta Wild Sheep the formation of the first ever through People & Peaks Productions. Foundation Northeastern Slopes Operator’s Susan is mentoring four youth in Steering Committee (NESOSC). In multimedia. They include Bailey Cheyenne Rig Repair September 2012, Laura Vinson was Storrie, Stephen McDonald, Morgan & Supply Ltd elected the Chairperson of the Sapach, and Thomas Houlihan. “Wild group—and we haven’t looked back Alberta: The Willmore Legacy” under her leadership. NESOSC hired (46 min) was premiered at the People AM Consulting & Joe Pavelka, the President of Planvision & Peaks Film Fest on Friday April 13, Maurice Nadeau Management Consulting Ltd. and his 2012, at the Jan Cinema in Grande partner Laura Ells as a consultant Prairie. A movie called Women of Bazil Leonard: North Eastern for ecotourism marketing. Both Willmore Wilderness (48 min) Photo by Sue Feddema-Leonard Fish & Game: Zone #5 have proven to be a great fit for our and an accompanying book will be traditional eastern slopes operations premiered/launched at the Whyte Willmore Wilderness Museum of the Canadian Rockies on Joe is an Associate Professor, Forgotten Trails is Photo by Joe Sonnenberg Foundation April 4, 2013 at 7 p.m. -

Willmore Wilderness Park Is Home to Cougars

Ancient glaciers, high mountain Park Guide peaks, thick forests and raging Wildlife Backcountry Hiking Contact rivers define these 4,597 km² of untamed wilderness. Backpackers and horseback riders seeking a true Willmore’s wildlife thrives in the natural Safety Many of the park’s well-established trails follow Alberta Parks backcountry experience can explore surroundings of the park. Grassy slopes provide in the historic footsteps of Aboriginal hunters, Web: albertaparks.ca over 750 km of trails where wildlife excellent winter ranges for sheep and goats. fur traders, coal miners and trappers. The Rock Hinton Office: 780–865–8395 abounds. Visitors to Willmore must Almost 20% of Alberta’s mountain goats and The wild and rugged nature of Willmore Lake staging area provides a popular access Visitor Centre: 780–865–5600 be experienced and well equipped 20% of the province’s bighorn sheep live in Wilderness is an irresistible draw for many into the Willmore via the Mountain Trail. For Toll Free: 1–866–427–3582 Willmore for backcountry adventure. Willmore and the park is also home to woodland visitors. Yet, the dangers of Willmore can provide those with only a few days to explore, Seep caribou, moose, elk, grizzly bears, black bears, a challenge for even the most seasoned outdoor Creek Trail soon heads north off the Mountain Fire Bans in Alberta Wilderness Park cougars, wolves, wolverine, and numerous small enthusiasts. Trail to provide quick entry into alpine country Web: albertafirebans.ca mammals. with plentiful wildlife and extensive views. Further Park Access • Only minimal trail maintenance occurs and along, Mountain Trail bends southwest and Emergency (Police, Fire, Ambulance) there are no developed campsites in the climbs to Eagle’s Nest Pass, offering a fine base Phone: 911 Hunting & Fishing park.