Regulating Payday Lenders in Canada: Drawing on American Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Name

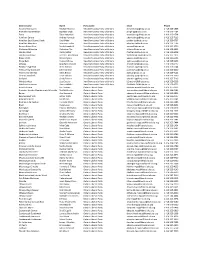

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Government of Ontario Key Contact Ss

GOVERNMENT OF ONTARIO 595 Bay Street Suite 1202 Toronto ON M5G 2C2 KEY CONTACTS 416 586 1474 enterprisecanada.com PARLIAMENTARY MINISTRY MINISTER DEPUTY MINISTER PC CRITICS NDP CRITICS ASSISTANTS Steve Orsini Patrick Brown (Cabinet Secretary) Steve Clark Kathleen Wynne Andrea Horwath Steven Davidson (Deputy Leader + Ethics REMIER S FFICE Deb Matthews Ted McMeekin Jagmeet Singh P ’ O (Policy & Delivery) and Accountability (Deputy Premier) (Deputy Leader) Lynn Betzner Sylvia Jones (Communications) (Deputy Leader) Lorne Coe (Post‐Secondary ADVANCED EDUCATION AND Han Dong Peggy Sattler Education) Deb Matthews Sheldon Levy Yvan Baker Taras Natyshak SKILLS DEVELOPMENT Sam Oosterhoff (Digital Government) (Digital Government) +DIGITAL GOVERNMENT (Digital Government) AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Jeff Leal Deb Stark Grant Crack Toby Barrett John Vanthof +SMALL BUSINESS ATTORNEY GENERAL Yasir Naqvi Patrick Monahan Lorenzo Berardinetti Randy Hillier Jagmeet Singh Monique Taylor Gila Martow (Children, Jagmeet Singh HILDREN AND OUTH ERVICES Youth and Families) C Y S Michael Coteau Alex Bezzina Sophie Kiwala (Anti‐Racism) Lisa MacLeod +ANTI‐RACISM Jennifer French (Anti‐Racism) (Youth Engagement) Jennifer French CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION Laura Albanese Shirley Phillips (Acting) Shafiq Qaadri Raymond Cho Cheri DiNovo (LGBTQ Issues) Lisa Gretzky OMMUNITY AND OCIAL ERVICES Helena Jaczek Janet Menard Ann Hoggarth Randy Pettapiece C S S (+ Homelessness) Matt Torigian Laurie Scott (Community Safety) (Community Safety) COMMUNITY SAFETY AND Margaret -

This Paper Seeks to Expand the Scope of These Two Seemingly Separate

Provincial-International Relations: Exploring the International Involvement of the Ontario Legislature Natalie Tutunzis, Ontario Legislature Internship Programme This paper seeks to explore the international involvement, or the international relations, of the Ontario Legislature. It will be shown that local parliamentarians, as exemplified by the involvement of the Ontario Legislature, have important roles to play internationally. Not only do provincial-international relations exist at the legislative level, but they occur quite frequently and in a diverse manner of ways. The paper will outline and describe such relations as they occur between the Ontario Legislature and foreign legislatures or other bodies, as exemplified through the Legislature’s involvement in interparliamentary organizations and delegations, as well as through the pursuit of international initiatives advanced by members, Officers, and affiliates of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. In addition to describing the actions that have and are currently taking place, the paper will begin a discussion about the general purposes of such international relations at the provincial parliamentary level, as well as discuss their perceived effectiveness. It will be argued that these relations have distinct purposes, which have, in many cases, achieved positive results. While literature on provincial-international legislative relations does exist, it is still remains quite sparse. However, the limited background that does exists on the matter nonetheless points to how frequently such relations occur, their significance, and even more so, how worthy they are of further exploration. Overall, this paper attempts to expand on the existing literature by providing an up-to-date account of the international involvement of provincial parliaments, using the Ontario Legislature as its case study. -

Ontario Government Quick Reference Guide: Key Officials and Opposition Critics August 2014

Ontario Government Quick Reference Guide: Key Officials and Opposition Critics August 2014 Ministry Minister Chief of Staff Parliamentary Assistant Deputy Minister PC Critic NDP Critic Hon. David Aboriginal Affairs Milton Chan Vic Dhillon David de Launay Norm Miller Sarah Campbell Zimmer Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs Hon. Jeff Leal Chad Walsh Arthur Potts Deb Stark Toby Barrett N/A Hon. Lorenzo Berardinetti; Sylvia Jones (AG); Jagmeet Singh (AG); Attorney General / Minister responsible Shane Madeleine Marie-France Lalonde Patrick Monahan Gila Martow France Gélinas for Francophone Affairs Gonzalves Meilleur (Francophone Affairs) (Francophone Affairs) (Francophone Affairs) Granville Anderson; Alexander Bezzina (CYS); Jim McDonell (CYS); Monique Taylor (CYS); Children & Youth Services / Minister Hon. Tracy Omar Reza Harinder Malhi Chisanga Puta-Chekwe Laurie Scott (Women’s Sarah Campbell responsible for Women’s Issues MacCharles (Women’s Issues) (Women’s Issues) Issues) (Women’s Issues) Monte Kwinter; Cristina Citizenship, Immigration & International Hon. Michael Christine Innes Martins (Citizenship & Chisanga Puta-Chekwe Monte McNaughton Teresa Armstrong Trade Chan Immigration) Cindy Forster (MCSS) Hon. Helena Community & Social Services Kristen Munro Soo Wong Marguerite Rappolt Bill Walker Cheri DiNovo (LGBTQ Jaczek Issues) Matthew Torigian (Community Community Safety & Correctional Hon. Yasir Brian Teefy Safety); Rich Nicholls (CSCS); Bas Balkissoon Lisa Gretzky Services / Government House Leader Naqvi (GHLO – TBD) Stephen Rhodes (Correctional Steve Clark (GHLO) Services) Hon. David Michael Government & Consumer Services Chris Ballard Wendy Tilford Randy Pettapiece Jagmeet Singh Orazietti Simpson Marie-France Lalonde Wayne Gates; Economic Development, Employment & Hon. Brad (Economic Melanie Wright Giles Gherson Ted Arnott Percy Hatfield Infrastructure Duguid Development); Peter (Infrastructure) Milczyn (Infrastructure) Hon. Liz Education Howie Bender Grant Crack George Zegarac Garfield Dunlop Peter Tabuns Sandals Hon. -

Regulating Payday Lenders in Canada: Drawing on American Lessons Stephanie Ben-Ishai Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected]

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy Papers Research Report No. 16/2008 Regulating Payday Lenders in Canada: Drawing on American Lessons Stephanie Ben-Ishai Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/clpe Recommended Citation Ben-Ishai, Stephanie, "Regulating Payday Lenders in Canada: Drawing on American Lessons" (2008). Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy. Research Paper No. 16/2008. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/clpe/189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference Papers at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. CLPE RESEARCH PAPER 16/2008 Stephanie Ben-Ishai Regulating Payday Lenders in Canada: Drawing on American Lessons EDITORS: Peer Zumbansen (Osgoode Hall Law School, Toronto, Director, Comparative Research in Law and Political Economy, York University), John W. Cioffi (University of California at Riverside), Lindsay Krauss (Osgoode Hall Law School, Toronto, Production Editor) This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Library at: http://ssrn.com/abstractid=1128147 CLPE RESEARCH PAPER XX/2007 • VOL. XX NO. XX (2007) CLPE Research Paper 16/2008 Vol. 04 No. 03 (2008) Stephanie Ben-Ishai REGULATING PAYDAY LENDERS IN CANADA: DRAWING ON AMERICAN LESSONS Abstract: The regulation of payday loans holds the potential of extending the benefits of regulating overindebtness, currently provided via bankruptcy legislation to the middle-class, to lower income debtors. -

THE HOLODOMOR MEMORIAL DAY ACT PROCEEDS to SECOND READING All Parties Work Together to Pass Legislation That Commemorates Victims of the Man-Made Famine of Ukraine

Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l’Ontario NEWS RELEASE / COMMUNIQUÉ THE HOLODOMOR MEMORIAL DAY ACT PROCEEDS TO SECOND READING All Parties Work Together To Pass Legislation That Commemorates Victims Of The Man-Made Famine of Ukraine NEWS March 5, 2009 Queen’s Park – Private Member’s Bill 147, the Holodomor Memorial Day Act proceeded to second reading at Queen’s Park today. This is the first tri-sponsored Private Member’s Bill by Dave Levac, Liberal MPP for Brant, Cheri DiNovo, NDP MPP for Parkdale-High Park, and Frank Klees, PC MPP for Newmarket-Aurora. If passed, this legislation will provide for the declaration of Holodomor Memorial Day on the fourth Saturday in November in each year in the Province of Ontario. The Holodomor is the name given to the man-made famine that occurred in Ukraine from 1932 to 1933, in which as many as 10 million Ukrainians perished as victims under Joseph Stalin’s regime to consolidate control over Ukraine, with 25,000 dying each day at the peak of the famine in 1933. Ukraine has established the fourth Saturday in November in each year as the annual day to commemorate the victims of the Holodomor. If passed, this Bill will extend the annual commemoration of the victims of the Holodomor to Ontario. QUOTES “Today is an important day for Ukrainian-Canadians and especially, for family and friends who fell victim of the Holodomor,” said MPP Dave Levac. “The remembrance of these horrors from the past requires our attention.” “Finally Ukrainian Canadians will have the respect for all the victims of Stalin's genocide they've been praying for in this Province,” said Cheri DiNovo, MPP Parkdale-High Park. -

A Bittersweet Day for Stryi Omits Patriarchal Issue, for Now Town Mourns One Hierarch and Celebrates Another

INSIDE: • The Kuchma inquiry: about murder or politics? – page 3. • Community honors Montreal journalist – page 8. • “Garden Party” raises $14,000 for Plast camp – page 10. THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal Wnon-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXIX No. 15 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 10, 2011 $1/$2 in Ukraine Meeting with pope, UGCC leader A bittersweet day for Stryi omits patriarchal issue, for now Town mourns one hierarch and celebrates another that we are that Church which is devel- oping, and each Eastern Church which is developing is moving towards a patri- archate, because a patriarchate is a natu- ral completion of the development of this Church,” the major archbishop said at his first official press conference, held on March 29. He was referring to the Synod of Bishops held March 21-24. The sudden reversal revealed that the otherwise talented major archbishop has already begun the process of learning the ropes of politics and the media, as indi- cated by both clergy and laity. Major Archbishop Shevchuk was accompanied by several bishops on his five-day visit to Rome, including Archbishop-Metropolitan Stefan Soroka of the Philadelphia Archeparchy, Bishop Paul Patrick Chomnycky of the Stamford Eparchy, and Bishop Ken Nowakowski Zenon Zawada of the New Westminster Eparchy. Father Andrii Soroka (left) of Poland and Bishop Taras Senkiv lead the funeral The entourage of bishops agreed that procession in Stryi on March 26 for Bishop Yulian Gbur. raising the issue of a patriarchate – when presenting the major archbishop for the by Zenon Zawada Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 86 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................96 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................94 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................95 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................96 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................98 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................99 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................96 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................96 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................98 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................96 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson................................98 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

Ontario Gazette Volume 140 Issue 43, La Gazette De L'ontario Volume 140

Vol. 140-43 Toronto ISSN 0030-2937 Saturday, 27 October 2007 Le samedi 27 octobre 2007 Proclamation ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, ELIZABETH DEUX, par la grâce de Dieu, Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada and Her other Realms and Territories, Queen, Head of the Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. Défenseur de la Foi. Family Day, the third Monday of February of every year, is declared a Le jour de la Famille, troisième lundi du mois de février de chaque année, holiday, pursuant to the Retail Business Holidays Act, R.S.O. 1990, est déclaré jour férié conformément à la Loi sur les jours fériés dans le Chapter R.30 and of the Legislation Act, 2006, S.O. 2006 c. 21 Sched. F. commerce de détail, L.R.O. 1990, chap. R.30, et à la Loi de 2006 sur la législation, L.O. 2006, chap. 21, ann. F. WITNESS: TÉMOIN: THE HONOURABLE L’HONORABLE DAVID C. ONLEY DAVID C. ONLEY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR OF OUR LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR DE NOTRE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO PROVINCE DE L’ONTARIO GIVEN at Toronto, Ontario, on October 12, 2007. FAIT à Toronto (Ontario) le 12 octobre 2007. BY COMMAND PAR ORDRE DAVID CAPLAN DAVID CAPLAN Minister of Government Services (140-G576) ministre des Services gouvernementaux Parliamentary Notice Avis parlementaire RETURN OF MEMBER ÉLECTIONS DES DÉPUTÉS Notice is Hereby Given of the receipt of the return of members on Nous accusons réception par la présente des résultats du scrutin, or after the twenty-sixth day of October, 2007, to represent -

Alive in the Heart of the City • Founded in 1847

Alive In The Heart Of The City Founded in 1847 The Church of the Holy Trinity DIOCESE of TORONTO The ANGLICAN CHURCH of CANADA 10 Trinity Square Toronto Ontario M5G1B1 (416) 598-4521 www.holytrinitytoronto.org Sixth Sunday after Pentecost th June 26 , 2015 10.30 am Holy Eucharist Welcome to Pride Sunday at Holy Trinity! We are delighted to have you with us this morning. Holy Trinity is an accessible, active, vibrant, justice-seeking, queer-positive community in the heart of downtown Toronto. We try to use language in our worship which includes us all, and we encourage the participation of each person in the worship and life of the Church. At the Exchange of Peace we move about freely, greeting one another. During the Offertory hymn we will move to create a circle around the altar for the Prayers of the People. All are welcome to share in the Eucharist as they feel comfortable. Assisting hearing devices are available. Please ask a Greeter or the Caretaker. The church is wheelchair accessible by South door. Scent Free Zone: Please refrain from wearing highly scented personal products. A special welcome, Newcomers! Please make yourself at home in this church. The Church of the Holy Trinity is a community of people who express Christian faith through lives of integrity, justice and compassion. We foster lay leadership, include the doubter and marginalized, and challenge oppression wherever it may be found. Mission Statement, 2010 The Church of the Holy Trinity www.holytrinitytoronto.org The Diocese of Toronto www.toronto.anglican.ca The Anglican Church of Canada www.anglican.ca Today’s Worship Team Coordinator Sherman Hesselgrave Celebrant Bill Whitla Musician Ian Grundy, Keith Nunn Readers Suzanne Rumsey, Sherman Hesselgrave, Matt McGeachy Homilist The Rev. -

Monday, April 20, 2017 Kathleen Wynne, Premier Legislative

Monday, April 20, 2017 Kathleen Wynne, Premier Legislative Building Queen's Park Toronto ON M7A 1A1 The Honourable Glen Murray Minister of the Environment and Climate Change 2nd Floor Macdonald Block, 900 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario M7A 1N3 Dear Premier Wynne and Minister Murray, We are asking that you require that the one-stop Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) project be evaluated in comparison with the five-stop Scarborough RT and with the seven-stop LRT that was originally planned to replace the Scarborough RT. As you are aware, the Environmental Assessment for the SSE is scheduled to commence shortly. Ontario’s Transit Project Assessment Process provides for the Premier and the Minister to take action if there is “potential for a negative impact on a matter of provincial importance that relates to the natural environment.” Accordingly, we believe: ● the SSE has the potential to exacerbate, rather than reduce, Ontario’s greenhouse gas emissions ● that building the seven-stop LRT instead, would reduce Ontario’s greenhouse gas emissions arising from transportation. Ontario faces a stiff challenge in achieving its climate change targets. The 2016 Annual GHG Progress Report of the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario warns that Ontario’s Climate Change Action Plan is unlikely to achieve the province’s 2020 target for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It cautions that “transportation is Ontario’s highest and fastest growing source of GHGs, “having increased over 27 per cent since 1990” and concludes that “reducing transportation emissions, must, therefore, be Ontario’s highest climate change priority.” There are numerous grounds for concern about the potential for negative environmental and social impact of the SSE: ● Design, construction and operation of the proposed 1-stop subway will not help reduce GHG emissions in a timely fashion. -

Queering Representation LGBTQ People and Electoral Politics in Canada

Queering Representation LGBTQ People and Electoral Politics in Canada Edited by Manon Tremblay UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL To all LGBTQ people who feel that representation is a foreign concept . UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL Contents List of Figures and Tables / ix Foreword / xi Rev. Dr. Cheri DiNovo Acknowledgments / xiii Introduction / 3 Manon Tremblay Part 1: LGBTQ Voters 1 Profi le of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Electorate in Canada / 51 Andrea M.L. Perrella, Steven D. Brown, and Barry Kay 2 Winning as a Woman/Winning as a Lesbian: Voter Attitudes toward Kathleen Wynne in the 2014 Ontario Election / 80 Joanna Everitt and Tracey Raney 3 Media Framing of Lesbian and Gay Politicians: Is Sexual Mediation at Work? / 102 Mireille Lalancette and Manon Tremblay 4 Electing LGBT Representatives and the Voting System in Canada / 124 Dennis Pilon Part 2: LGBTQ Representatives 5 LGBT Groups and the Canadian Conservative Movement: A New Relationship? / 157 Frédéric Boily and Ève Robidoux-Descary UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL viii Contents 6 Liberalism and the Protection of LGBT Rights in Canada / 179 B r o o k e J e ff rey 7 A True Match? Th e Federal New Democratic Party and LGBTQ Communities and Politics / 201 Alexa DeGagne 8 Representation: Th e Case of LGBTQ People / 220 Manon Tremblay 9 Pathway to Offi ce: Th e Eligibility, Recruitment, Selection, and Election of LGBT Candidates / 240 Joanna Everitt, Manon Tremblay, and Angelia Wagner 10 LGBTQ Perspectives on Political Candidacy in Canada / 259 Angelia Wagner 11 Out to Win: Th e ProudPolitics Approach to LGBTQ Electoralism / 279 Curtis Atkins 12 LGBT Place Management: Representative Politics and Toronto’s Gay Village / 298 Catherine J.