Dissertation Economics, Politics and Ecology Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structural and Functional Responses of Sunflower and Tobacco Grown on A

Structural and functional responses of sunflower and tobacco grown on a Cu-contaminated soil series Aliaksandr Kolbas, Michel Mench, Natallia Kolbas, Lilian Marchand, Rolf Herzig To cite this version: Aliaksandr Kolbas, Michel Mench, Natallia Kolbas, Lilian Marchand, Rolf Herzig. Structural and functional responses of sunflower and tobacco grown on a Cu-contaminated soil series. 9. International Phytotechnology Society (IPS), Sep 2012, Hasselt, Belgium. 410 p., 2012. hal-02748876 HAL Id: hal-02748876 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02748876 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PREFACE Phytotechnologies - plant-based strategies to clean water, soil, air and provide ecosystem services - have an effective power beyond their science when integrated into our managed landscapes. The aim of the 9th IPS Conference on Phytotechnologies is to exchange information, experience and achievements in all plant-based technologies adopted to mitigate environmental problems, evaluate currently applied technologies and present innovative ideas. The presented plant-based technologies are not limited to phytoremediation, but also include biofuel production on degraded soils, green-roof technology, treatment wetlands, landfill caps, and carbon sequestration among others. The organizers strongly believe in the active participation of young scientists in the conference. -

UWA Study Centre @ ZJU 西澳大学学习中心@浙江大学

UWA Study Centre @ ZJU 西澳大学学习中心@浙江大学 UWALC@ZJU HuangZhou 杭州 / HuaJiaChi 华家池 为何选择西澳大学学习中心? Why UWA Study Centre? 西澳大学希望向在 COVID-19 边境限制期间,为无法返回珀斯学习 的西澳大学中国学生们提供更多支持以及学术帮助。 UWA would like to provide additional support to its Chinese students who are unable to return to Perth while COVID-19 border restrictions are in place. • 使用浙江大学校内设施 Using the campus facilities at Zhejiang University • 与同样来自西澳大学的同学们一起学习和生活 Live and study with other UWA students • 参与学生社团以及社团活动 Join the UWA student committee and activities 为何选择西澳大学学习中心? Why UWA Study Centre? • 西澳大学的学生可以使用浙江大学华家池校区及西溪校区 The UWA student can use Zhejiang University HuaJiaChi and XiXi campus • 浙江大学华家池校区将提供UWA学生专用教室 Dedicated UWA classrooms will be provided at HuaJiaChi campus • 将有浙江大学的教师们为学生提供学术帮助 Zhejiang University will provide academic support to UWA students • 西澳大学学习中心将举办各类学生活动 Student activities and events will be arranged by UWA Study Centre 杭州 HANGZHOU 杭州是浙江省的省会 Hangzhou is the capital city of Zhejiang Province 位于中国东南沿海、浙江省北部,钱塘江下游 Located on the southeast coast of China, the north of Zhejiang Province, and the lower reaches of the Qiantang River 全国十大城市之一 One of the tenth largest cities in the China. 并被《福布斯》多次评为中国大陆最佳商业城市 Has been rated as the best commercial city in mainland China by Forbes multiple times 八大古都之一,其盛名又以西湖为首 One of the eight ancient capitals, its reputation is led by West Lake 杭州 西湖 / Hangzhou West Lake 灵隐寺 / Lingyin Temple 河坊街 / Hefang Street Sceneic Area 西溪国家湿地公园 Xixi National Wetland Park 浙江大学 ZHEJIANG UNIVERSITY • 创立于1897 Found in 1897 • 全中国排名前三的院校之一 (ARWU 2019,2020,2021) -

Nilaparvata Lugens

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Interactions between brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) and salinity stressed rice (Oryza sativa) plant are cultivar-specifc Md Khairul Quais1,2, Asim Munawar1, Naved Ahmad Ansari1, Wen-Wu Zhou1 & Zeng-Rong Zhu1 ✉ Salinity stress triggers changes in plant morphology, physiology and molecular responses which can subsequently infuence plant-insect interactions; however, these consequences remain poorly understood. We analyzed plant biomass, insect population growth rates, feeding behaviors and plant gene expression to characterize the mechanisms of the underlying interactions between the rice plant and brown planthopper (BPH) under salinity stress. Plant bioassays showed that plant growth and vigor losses were higher in control and low salinity conditions compared to high salinity stressed TN1 (salt- planthopper susceptible cultivar) in response to BPH feeding. In contrast, the losses were higher in the high salinity treated TPX (salt-planthopper resistant cultivar). BPH population growth was reduced on TN1, but increased on TPX under high salinity condition compared to the control. This cultivar-specifc efect was refected in BPH feeding behaviors on the corresponding plants. Quantifcation of abscisic acid (ABA) and salicylic acid (SA) signaling transcripts indicated that salinity-induced down-regulation of ABA signaling increased SA-dependent defense in TN1. While, up-regulation of ABA related genes in salinity stressed TPX resulted in the decrease in SA-signaling genes. Thus, ABA and SA antagonism might be a key element in the interaction between BPH and salinity stress. Taken together, we concluded that plant-planthopper interactions are markedly shaped by salinity and might be cultivar specifc. Plants are ofen exposed to multiple abiotic and biotic stressors at the same time in nature. -

Precision Livestock Farming ’05

Precision Livestock Farming ’05 Edited by S. Cox Precision Livestock Farming ’05 Precision Livestock Farming ’05 Edited by S. Cox Wageningen Academic Publishersb s e s All rights reserved. Nothing from this publication may be repro- duced, stored in a computerised system or published in any form or in any manner, Subject headings: including electronic, mechanical, Livestock management reprographic or photographic, without prior Livestock monitoring written permission from the publisher, Improved handling of waste products Wageningen Academic Publishers, P. O. Box 220, NL-6700 AE Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 907699868X The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from First published, 2005 them remain the responsibility of the authors. The publisher is not responsible for possible Wageningen Academic Publishers damages, which could be a result of content The Netherlands, 2005 derived from this publication. Reviewers Andy Frost Great Britain Christina Umstaetter Germany Daniel Berckmans Belgium David Filmer Great Britain Dieter Ordolff Germany Henk Hogeveen The Netherlands Joachim Krieter Germany Jos Metz The Netherlands Lars Schrader Germany Lars Thylén Sweden Robert Kaufmann Switzerland Rony Geers Belgium Sidney Cox Great Britain Thomas Jungbluth Germany Organisers JTI, Swedish Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Engineering SLU, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Editor of the ECPLF Proceedings Sidney Cox Great Britain Country representatives for ECPLF Sidney Cox, Editor Andy Frost Great Britain Daniel Berckmans Belgium Krister Sällvik Sweden Reiner Brunsch Germany Robert Kaufmann Switzerland Soeren Pedersen Denmark Kees Lokhorst The Netherlands Lars Thylén, Chairperson Program Committee Lars Thylén JTI, Uppsala Börje Lindén SLU, Uppsala Krister Sällvik SLU, Uppsala Tomas Kätterer SLU, Uppsala Mikael Gilbertsson JTI, Uppsala Jan Olofsson SLU, Uppsala Precision Livestock Farming ’05 7 Contents Editorial 13 Sidney Cox Keynotes 15 Field effect transistors in precision agriculture 17 Ernst J.R. -

Annual Report 2020 Corporate Information

(Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 3316.HK 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Contents Corporate Information 2 Financial Summary 4 Chairman’s Statement 6 Management Discussion and Analysis 9 Directors and Senior Management 24 Directors’ Report 31 Corporate Governance Report 50 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 65 Independent Auditor’s Report 100 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 106 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 108 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 110 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 111 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 112 Corporate Information Board of Directors Joint Company Secretaries Executive Directors Ms. ZHONG Ruoqin Ms. KO Mei Ying Mr. ZHU Lidong (Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer) Ms. ZHONG Ruoqin Authorized Representatives Ms. ZHONG Ruoqin Non-executive Directors Ms. KO Mei Ying Mr. MO Jianhua Mr. CAI Xin Legal Advisor Morrison & Foerster Independent Non-executive Directors 33/F, Edinburgh Tower Mr. DING Jiangang The Landmark Mr. LI Kunjun 15 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong Ms. CAI Haijing Auditor Audit Committee KPMG Ms. CAI Haijing (Chairman) Public Interest Entity Auditor Mr. DING Jiangang registered in accordance with the Mr. LI Kunjun Financial Reporting Council Ordinance 8th Floor, Prince’s Building Remuneration Committee 10 Chater Road Central Mr. DING Jiangang (Chairman) Hong Kong Mr. MO Jianhua Ms. CAI Haijing Compliance Adviser Nomination Committee Southwest Securities (HK) Capital Limited 40/F, Lee Garden One Mr. ZHU Lidong (Chairman) 33 Hysan Avenue Mr. DING Jiangang Causeway Bay Mr. LI Kunjun Hong Kong Strategy Committee Principal Banks Mr. MO Jianhua (Chairman) China Construction Bank Corporation Mr. -

ENVIS CENTER on ENVIRONMENTAL BIOTECHNOLOGY

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. ENVIS CENTER on ENVIRONMENTAL BIOTECHNOLOGY Abstract Vol. XVI Sponsored by MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI Department of Environmental Science University of Kalyani Nadia, West Bengal June, 2010 Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. Published by: Prof. S. C. Santra Co-ordinator ENVIS Centre of Environmental Biotechnology Department of Environmental Science University of Kalyani, Kalyani –741235, Nadia, West Bengal, INDIA Email: [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] Website: http://www.kuenvbiotech.org Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. ENVIS CENTRE on ENVIRONMENTAL BIOTECHBNOLOGY Prof. S. C. Santra : Coordinator, ENVIS Centre ENVIS’s Staff 1. Dr. Nandini Gupta : Programme Officer 2. Ms. Amrita Saha : Information Officer (Deb Chaudhury) 3. Shri S. Bandyopadhyay : Data Entry Operator Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. C O N T E N T S Sl. Title Page No. No. 1. Background 5 2. Abstract format 6 3. General information 7 4. Abbreviation used 10 5. Abstracts Bioaccumulation 13 Bioremediation 21 Biotransformation 61 Biomarker 69 Biofertilizer 72 Biocomposting 73 Biopesticide 74 Biodegradation 85 Biosensor 121 Bioengineering 132 Pollen Biotechnology 133 Biotechnology Policy Issue 133 Agricultural Biotechnology 134 Bioenergy 134 6. Name of Journal 153 7. Author Index 156 Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. ENVIS Centre on Environmental Biotechnology BACKGROUND Environmental Information System (ENVIS) is established in the year 1984 as a network of Information Centres. -

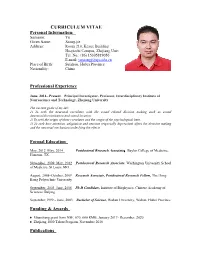

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Information: Surname: Yu Given Name: Xiong-Jie Address: Room 210, Kexue Building Huajiachi Campus, Zhejiang Univ Tel

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Information: Surname: Yu Given Name: Xiong-jie Address: Room 210, Kexue Building Huajiachi Campus, Zhejiang Univ Tel. No.: (86) 15305819056 E-mail: [email protected] Place of Birth: Suizhou, Hubei Province Nationality: China Professional Experience June, 2014– Present Principal Investigator, Professor, Interdisciplinary Institute of Neuroscience and Technology, Zhejiang University The current goals of my lab: 1) To seek the neuronal correlates with the sound related dicision making such as sound detection/discrimination and sound location. 2) To seek the origin of these correlates and the origin of the psychological limit. 3) To seek how attention, adaptation and emotion (especially depression) affect the decision making and the neuronal mechanism underlying the effects Formal Education May, 2012–May, 2014 Postdoctoral Research Associate,Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX. November, 2009–May, 2012 Postdoctoral Research Associate, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO. August, 2008–October, 2009 Research Associate, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University September, 2003–June, 2008 Ph.D Candidate, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing September,1999 – June, 2003 Bachelor of Science, Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei Province Funding & Awards Mianshang grant from NSF, 670, 000 RMB, January 2017- December, 2020 Zhejiang 1000 Talent Program, November 2016 Publications Yu XJ*, J. David Dickman, Gregory C. DeAngelis, and Dora E. Angelaki*. Neuronal thresholds and choice-related activity of otolith afferent fibers during heading perception.(2015) PNAS 112 (20): 6467-6472 Xu XX, Zhai YY, Kou XK and Yu XJ*.Spatial Stimulus-specific adaptation facilitates the spatial discrimination through sharpening the response contrast in the thalamic reticular nucleus of rat (2016) (Under review). -

Appendix V Statutory and General Information

APPENDIX V STATUTORY AND GENERAL INFORMATION A. FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT OUR GROUP 1. Incorporation of Our Company We were incorporated in the Cayman Islands under the Cayman Companies Act as an exempted company with limited liability on May 13, 2020. We have established a principal place of business in 3401A, Windsor House, 311 Gloucester Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong and was registered as a non-Hong Kong company under Part 16 of the Companies Ordinance on July 22, 2020 under Part 16 of the Companies Ordinance. Mr. ZHAO Hong and Ms. PAN Rongrong have been appointed as our authorized representatives for the acceptance of service of process and notices on behalf in Hong Kong. As we were incorporated in the Cayman Islands, our operations are subject to the Cayman Companies Act and to our constitution comprising our Memorandum and the Articles of Association. A summary of certain provisions of our constitution and relevant aspects of the Cayman Companies Act is set out in Appendix IV to this prospectus. 2. Changes in Our Share Capital As of the date of incorporation of our Company, our authorized share capital was USD50,000 divided into 1,000,000,000 Shares of a par value of USD0.00005 each. The following sets out the changes in our Company’s share capital from the incorporation of the Company to the date of the issue of this prospectus. (a) On May 13, 2020, our Company issued one Share with a par value of USD0.00005 to Mapcal Limited, which was subsequently transferred to GL GLEE Investment Limited on the same day; (b) On June 24, 2020, our Company issued and allotted an aggregate of 543,135,510 Shares to the following persons: Number of Number of Name Shares Allotted Shares Held Consideration paid GL Trade Investment L.P. -

A Study on College Campus Cultural and Ecological Environment Value Based on Cvm —— Taking Huajiachi Campus As an Example

The CRIOCM 2006 International Symposium on “Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate” A STUDY ON COLLEGE CAMPUS CULTURAL AND ECOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT VALUE BASED ON CVM —— TAKING HUAJIACHI CAMPUS AS AN EXAMPLE Shi Zhong WANG1, 2, Wei Dong LIU1 1. Land Resources Management Dep. Zhejiang University,Hangzhou,China 2. Research Center for Real Estate, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economy,Hangzhou,China Abstract: CVM,as a means of measuring and evaluating the value of environment, has been used more and more widely and commonly in foreign developed countries. But, in china, it is just a start and study cases by using CVM are very few. It is very common in our country’s college taking land exchange as a way to expand its size, and this must result in the loss of old campus cultural and ecological environment value. These are the most important part of a college. This paper, by using CVM and taking Huajiachi (one campus of Zhejiang University) as an example, tries to evaluate the economic value of campus cultural and ecological environment, and analyze its bias existing in the course of evaluation. Key words: college campus; contingent valuation method; willingness to pay; bias analysis 1 Introduction CVM, also called evaluation according to willingness to pay or evaluation by hypothesis, is lately the most widely used standard evaluating method on public property value especially in the domain of natural resources in zoology and environment economics in home and abroad. In the hypothesis of marketing condition, CVM obtains the usage and non-usage value of environment resources by deducing the public’s willingness to pay or willingness to accept compensation for environment resources [1]. -

Determination of Soil Microbial Biomass Phosphorus in Acid Red Soils from Southern China

Biol Fertil Soils (2004) 39:446–451 DOI 10.1007/s00374-004-0734-6 ORIGINAL PAPER G.-C. Chen · Z.-L. He Determination of soil microbial biomass phosphorus in acid red soils from southern China Received: 1 July 2003 / Accepted: 4 February 2004 / Published online: 3 March 2004 Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract A CHCl3 fumigation and 0.03 M NH4F- microbial biomass P than the NaHCO3 extraction method 0.025 M HCl extraction procedure was used to measure in acid red soils. microbial biomass P (Pmic) in 11 acid red soils (pH <6.0) from southern China and the results compared to those Keywords Fumigation-extraction method · Microbial obtained by the commonly-used CHCl3 fumigation and biomass phosphorus · Acid red soils 0.5 M NaHCO3 extraction method. Extraction with NH4F- HCl was found to be more effective and accurate than NaHCO3 extraction for detecting the increase of P from Introduction microbial biomass P following chloroform fumigation due to its higher efficiency in extracting both native labile Soil organisms are the driving force behind C turnover phosphate and added phosphate (32P) in the soils. This and plant nutrient transformations and play an important was confirmed by the recovery of 32P from in situ 32P- role in soil fertility and ecosystem functioning (Smith and labeled soil microbial biomass following fumigation and Paul 1990). Both microbial biomass and activity can be extraction by the NH4F-HCl solution. Soil microbial used as an indicator of nutrient availability and the effect biomass P, measured by the NH4F-HCl extraction meth- of agricultural practices and environmental impact on soil od, was more comparable with soil microbial biomass C sustainability for agriculture. -

International Graduate Student Handbook

International Graduate Student Handbook 1 What is Control Science and Engineering? "Control Science and Engineering are scientific methods and technology that improve efficiency, productivity, quality, and reliability, specifically for machines and systems operating in structured environments over long periods, and the explicit structuring of environments." The coverage of Control Science and Engineering (CSE) goes beyond their roots in advanced aerospace applications and mass production, and include many new applications areas, such as Biotechnology, pharmaceutical, and health care; Home, service, and retail; Construction, transportation, and security; Manufacturing, maintenance, and supply chains; and Food handling and processing. 2 目 录 Welcome from the Dean of CSE College................................................................................... 1 General Policies.............................................................................................................................. 3 The Graduate School.............................................................................................................3 The International College...................................................................................................... 3 Academic Definition:PhD/Master Degree........................................................................3 Academic Integrity.................................................................................................................. 4 Period of Study........................................................................................................................4 -

Global Offering

祥生控股(集團)有限公司 SHIN SUN HOLDINGS (GROUP) CO., LTD. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code : 2599 GLOA B L OFFERING Joint Sponsors, Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers IMPORTANT IMPORTANT: If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this Prospectus, you should seek independent professional advice. Shinsun Holdings (Group) Co., Ltd. 祥生控股(集團)有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) GLOBAL OFFERING Number of Offer Shares under the : 600,000,000 Shares (subject to the Global Offering Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares : 60,000,000 Shares (subject to reallocation) Number of International Offer Shares : 540,000,000 Shares (subject to reallocation and the Over-allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price : HK$6.20 per Hong Kong Offer Share, plus brokerage fee of 1%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% and Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars and subject to refund) Nominal value : US$0.01 per Share Stock code : 2599 Joint Sponsors, Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers CRIC SECURITIES CO. LTD Joint Lead Managers Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this Prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Prospectus.