A Georgian Suburb: Revealing Place and Person in London's Camden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our Student Guide for Over-18S

St Giles International London Highgate, 51 Shepherds Hill, Highgate, London N6 5QP Tel. +44 (0) 2083400828 E: [email protected] ST GILES GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AGED 18 LONDON IGHGATE AND OVER H Contents Part 1: St Giles London Highgate ......................................................................................................... 3 General Information ............................................................................................................................. 3 On your first day… ............................................................................................................................... 3 Timetable of Lessons ............................................................................................................................ 4 The London Highgate Team ................................................................................................................. 5 Map of the College ............................................................................................................................... 6 Courses and Tests ................................................................................................................................. 8 Self-Access ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Rules and Expectations ...................................................................................................................... 10 College Facilities ............................................................................................................................... -

Buses from Finchley South 326 Barnet N20 Spires Shopping Centre Barnet Church BARNET High Barnet

Buses from Finchley South 326 Barnet N20 Spires Shopping Centre Barnet Church BARNET High Barnet Barnet Underhill Hail & Ride section Great North Road Dollis Valley Way Barnet Odeon New Barnet Great North Road New Barnet Dinsdale Gardens East Barnet Sainsburys Longmore Avenue Route finder Great North Road Lyonsdown Road Whetstone High Road Whetstone Day buses *ULIÀQ for Totteridge & Whetstone Bus route Towards Bus stops Totteridge & Whetstone North Finchley High Road Totteridge Lane Hail & Ride section 82 North Finchley c d TOTTERIDGE Longland Drive 82 Woodside Park 460 Victoria a l Northiam N13 Woodside i j k Sussex Ring North Finchley 143 Archway Tally Ho Corner West Finchley Ballards Lane Brent Cross e f g l Woodberry Grove Ballards Lane 326 Barnet i j k Nether Street Granville Road NORTH FINCHLEY Ballards Lane Brent Cross e f g l Essex Park Finchley Central Ballards Lane North Finchley c d Regents Park Road Long Lane 460 The yellow tinted area includes every Dollis Park bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Regents Park Road Long Lane Willesden a l miles from Finchley South. Main stops Ballards Lane Hendon Lane Long Lane are shown in the white area outside. Vines Avenue Night buses Squires Lane HE ND Long Lane ON A Bus route Towards Bus stops VE GR k SP ST. MARY’S A EN VENUE A C V Hail & Ride section E E j L R HILL l C Avenue D L Manor View Aldwych a l R N13 CYPRUS AVENUE H House T e E R N f O Grounds East Finchley East End Road A W S m L E c d B A East End Road Cemetery Trinity Avenue North Finchley N I ` ST B E O d NT D R D O WINDSOR -

Buses from Holborn Circus and Chancery Lane BRIXTON

HOLLOWAY ILFORD KENTISH HACKNEY TOWN ISLINGTON SHOREDITCH BETHNAL GREEN Buses from Holborn Circus and Chancery Lane BRIXTON 24 hour Northumberland Park 341 service 17 Tesco and IKEA Key continues to Maida Vale Archway Northumberland Park N8 Hall Road Hainault 8 Day buses in black The Lowe Lansdowne Road St JohnÕs Wood 24 hour N8 Night buses in blue Swiss Cottage Upper Holloway 25 service Wanstead Ilford Bruce Grove Hainault Street —O Connections with London Underground Warwick Avenue FitzjohnÕs Avenue HOLLOWAY o Connections with London Overground Holloway Tottenham Leytonstone Ilford Hampstead NagÕs Head Police Station Green Man 24 hour R Connections with National Rail West Green Road 242 service ILFORD Paddington Caledonian Road Homerton Hospital BishopÕs Bridge Road Philip Lane Leytonstone Manor Park DI Connections with Docklands Light Railway Harringay Green Lanes Broadway Clapton Park B Royal Free Hospital Caledonian Road & Barnsbury Connections with river boats Lancaster Gate Manor House Millfields Road Woodgrange 46 Leytonstone Park I Mondays to Fridays only Hackney Downs Hampstead Heath Green Lanes High Road South End Green Caledonian Road Forest Gate Copenhagen Street Lordship Park Newington Green Hackney Central Maryland Princess Alice Kentish Town West Caledonian Road Stratford Carnegie Street Newington Green Road Graham Road Balls Pond Road Bus Station KENTISH Kentish Town Road HACKNEY Essex Road Caledonian Road Stratford High Street Killick Street Dalston Junction TOWN Royal Camden Road Essex Road Old Ford College Pancras -

Ward Profile 2020 West Hampstead Ward

Ward Profile 2020 Strategy & Change, January 2020 West Hampstead Ward The most detailed profile of West Hampstead ward is from the 2011 Census (2011 Census Profiles)1. This profile updates information that is available between censuses: from estimates and projections, from surveys and from administrative data. Location West Hampstead ward is located to the north-west of Camden. It is bordered to the north by Fortune Green ward; to the east by Frognal and Fitzjohns ward; to the south by Kilburn ward and Swiss Cottage ward; and to the west by the London Borough of Brent. Population The current resident population2 of West Hampstead ward at mid-2019 is 14,100 people, ranking 7th largest ward by population size. The population density is 159 persons per hectare, ranking 7th highest in Camden, compared to the Camden average of 114 persons per hectare. Since 2011, the population of West Hampstead has grown faster than the overall population of Camden (at 17.2% compared with 13.4%), the 3rd fastest growing ward on percentage population change since 2011. 1 Further 2011 Census cross-tabulations of data are available (email [email protected]). 2 GLA 2017-based Projections ‘Camden Development, Capped AHS’, © GLA, 2019. 1 West Hampstead’s population is projected to increase by 1,900 (13.1%) over the next 10 years to 2029. The components of population change show a positive natural change (more births than deaths) over the period of +1,200 and net migration of +600. Births in the wards are forecast to be stable at the current level of 180 a year, while deaths are forecast to increase from the current level of 50, increasing to 60 by 2029. -

Download Brochure

A JEWEL IN ST JOHN’S WOOD Perfectly positioned and beautifully designed, The Compton is one of Regal London’ finest new developments. ONE BRING IT TO LIFE Download the FREE mobile Regal London App and hold over this LUXURIOUSLY image APPOINTED APARTMENTS SET IN THE GRAND AND TRANQUIL VILLAGE OF ST JOHN’S WOOD, LONDON. With one of London’s most prestigious postcodes, The Compton is an exclusive collection of apartments and penthouses, designed in collaboration with world famous interior designer Kelly Hoppen. TWO THREE BRING IT TO LIFE Download the FREE mobile Regal London App and hold over this image FOUR FIVE ST JOHN’S WOOD CULTURAL, HISTORICAL AND TRANQUIL A magnificent and serene village set in the heart of London, St John’s Wood is one of the capital’s most desirable residential locations. With an attractive high street filled with chic boutiques, charming cafés and bustling bars, there is never a reason to leave. Situated minutes from the stunning Regent’s Park and two short stops from Bond Street, St John’s Wood is impeccably located. SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE CHARMING LOCAL EATERIES AND CAFÉS St John’s Wood boasts an array of eating and drinking establishments. From cosy English pubs, such as the celebrated Salt House, with fabulous food and ambience, to the many exceptional restaurants serving cuisine from around the world, all tastes are satisfied. TEN TWELVE THIRTEEN BREATH TAKING OPEN SPACES There are an abundance of open spaces to enjoy nearby, including the magnificent Primrose Hill, with spectacular views spanning across the city, perfect for picnics, keeping fit and long strolls. -

Units 1 & 2 Hampstead Gate

UNITS 1 & 2 HAMPSTEAD GATE FROGNAL | HAMPSTEAD | LONDON | NW3 FREEHOLD OFFICE BUILDING FOR SALE AVAILABLE WITH FULL VACANT POSSESSION & 4 CAR SPACES 3,354 SQFT / 312 SQM (CAPABLE OF SUB DIVISION TO CREATE TWO SELF CONTAINED BUILDINGS) OF INTEREST TO OWNER OCCUPIERS AND/OR INVESTORS www.rib.co.uk INVESTMENT SUMMARY www.rib.co.uk • 2 INTERCONNECTING OFFICE BUILDINGS CAPABLE OF SUB DIVISION (TWO MAIN ENTRANCES) • 4 CAR PARKING SPACES • CLOSE PROXIMITY TO FINCHLEY ROAD UNDERGROUND STATION AND THE O² CENTRE • FREEHOLD • AVAILABLE WITH FULL VACANT POSSESSION SUMMARY www.rib.co.uk F IN C H LE Y HAMPSTEAD R F O I A GATE T EST D Z J HAMPSTEAD O Belsie Park H N H ’ A S V E A R V S Finchle Rd & Fronall T E O N CK U H E IL West Hampstead 2 L W O2 Centre E S ESIE PA T Finchle Rd E N D SUTH Swiss Cottae Chalk Farm L A D K HAMPSTEAD E ROA IL N AID BURN DEL E A HI OAD G E R H SIZ RO L E B F A I D N C H L E Y A B R A O V PIMSE HI B E E A Y N D D A R U RO E RT O E A R LB D O A A CE St ohns Wood D IN PR M IUN A W ID E A L L V I A N L G E T O EGENTS PA N R O A D LOCATION DESCRIPTION Hampstead Gate is situated close to the junction with Frognal and Comprise two interconnecting office buildings within a purpose-built Finchley Road (A41) which is one of the major commuter routes development. -

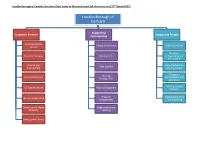

London Borough of Camden Structure Chart Down to Divisional Level (All Charts Are As of 27 March 2017)

th London Borough of Camden Structure Chart down to Divisional Level (all charts are as of 27 March 2017) London Borough of Camden Supporting Corporate Services Supporting People Communities Communications Community Services Adult Social Care Service Children's Customer Services Development Safeguarding and Social Work Finance and Early Intervention High Speed II Procurement and Prevention Education Housing Human Resources (Achievement and Management Aspiration) Housing Support ICT Shared Service Place Management Services Property Strategic and Joint Law and Governance Management Commissioning North London Waste Regeneration and Authority Planning Strategy and Change Corporate Services Structure Chart down to Organisation Level (Chart 1 of 2) Corporate Services (Chart 1 of 2) Communications Service Customer Services (395) Finance and Procurement Human Resources (72) (36) (101) Communications Benefits (51) Benefits (48) Change Team (4) Human Resources – AD Financial Management Service Team (26) Workflow and Scanning (3) Finance Support Team (17) & Strategic Leads (6) and Accountancy (25) Financial Management and Accountancy (1) Financial Reporting (3) Creative Service (5) Administration and Reception (15) Human Resources - Ceremonies and Citizenship Business Advisors (17) Contact Camden (3) Anti-Fraud and Investigations Team (3) Customer Insight and Improvement (11) Internal Audit and Risk Internal Audit and Risk (11) Contact Camden (210) (9) Internal AUDIT Team (4) Print Service (3) Customer Service Team (72) Human Resources – Digital -

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

86 Mill Lane

AVAILABLE TO LET 86 Mill Lane 86 Mill Lane, West Hampstead, London NW6 1NL Prominent retail shop in the heart of Mill Lane West Hamsptead 86 Mill Lane Prominent retail shop in the Rent £14,500 per annum heart of Mill Lane West Rates detail The property will need to Hamsptead be re assessed for Business Rates following Mill Lane is a popular street in West Hampstead and the refurbishment. benefits from a wide range of retailers and is favoured by professionals with Accountants, Surveyors and Building type Retail Opticians close by. Planning class A1 86 Mill Lane has undergone a complete refurbishment and benefits from a new kitchenette and w/c. Both the Secondary classes A2 ground and basement are open plan. The office could be suitable for both A1 and A2 Size 416 Sq ft occupiers. VAT charges No VAT payable on the Available now. rent. Lease details A new Full Repairing and Insuring lease Outside the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 for a term by arrangement. EPC category C EPC certificate Available on request Marketed by: Dutch & Dutch For more information please visit: http://example.org/m/39855-86-mill-lane-86-mill-lane 86 Mill Lane Recently refurbished shop / office Brand new kitchenette and W/C Forecourt Ample pay and display parking on Mill Lane Located close to the Hillfield Road (CS bus stop) 11 ft frontage Spot lights No VAT 86 Mill Lane 86 Mill Lane 86 Mill Lane, 86 Mill Lane, West Hampstead, London NW6 1NL Data provided by Google 86 Mill Lane Floors & availability Floor Size sq ft Status Ground 238 Available Basement 178 Available Total 416 Location overview The premises is situated mid-way along Mill Lane in West Hampstead on the southern side of the thoroughfare between the junction of Broomsleigh Street and Ravenshaw Street. -

EVERSHOLT STREET London NW1

245 EVERSHOLT STREET London NW1 Freehold Property For Sale Well let restaurant and first floor flat situated in the Euston Regeneration Zone Building Exterior 245 EVERSHOLT STREET Description 245 Eversholt Street is a period terraced property arranged over ground, lower ground and three upper floors. It comprises a self-contained restaurant unit on ground and lower ground floors and a one bedroom residential flat at first floor level. The restaurant is designed as a vampire themed pizzeria, with a high quality, bespoke fit out, including a bar in the lower ground floor. The first floor flat is accessed via a separate entrance at the front of the building and has been recently refurbished to a modern standard. The second and third floor flats have been sold off on long leases. Location 245 Eversholt Street is located in the King’s Cross and Euston submarket, and runs north to south, linking Camden High Street with Euston Road. The property is situated on the western side of the north end of Eversholt Street, approximately 100 metres south of Mornington Crescent station, which sits at the northern end of the street. The property benefits from being in walking distance of the amenities of the surrounding submarkets; namely Camden Town to the north, King’s Cross and Euston to the south, and Regent’s Park to the east. Ground Floor Communications The property benefits from excellent transport links, being situated 100m south of Mornington Crescent Underground Station (Northern Line). The property is also within close proximity to Camden Town Underground Station, Euston (National Rail & Underground) and Kings Cross St Pancras (National Rail, Eurostar and Underground). -

Life Expectancy

HEALTH & WELLBEING Highgate November 2013 Life expectancy Longer lives and preventable deaths Life expectancy has been increasing in Camden and Camden England Camden women now live longer lives compared to the England average. Men in Camden have similar life expectancies compared to men across England2010-12. Despite these improvements, there are marked inequalities in life expectancy: the most deprived in 80.5 85.4 79.2 83.0 Camden will live for 11.6 (men) and 6.2 (women) fewer years years years years years than the least deprived in Camden2006-10. 2006-10 Men Women Belsize Longer life Hampstead Town Highgate expectancy Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Camden Town with Primrose Hill St Pancras and Somers Town Hampstead Town Camden Town with Primrose Hill Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Belsize West Hampstead Regent's Park Bloomsbury Cantelowes King's Cross Holborn and Covent Garden Camden Camden Haverstock average2006-10 average2006-10 Gospel Oak St Pancras and Somers Town Highgate Cantelowes England England Haverstock 2006-10 Holborn and Covent Garden average average2006-10 West Hampstead Regent's Park King's Cross Gospel Oak Bloomsbury Shorter life Kentish Town Kentish Town expectancy Kilburn Kilburn Note: Life expectancy data for 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 90 88 86 84 82 80 78 76 74 72 70 wards are not available for 2010-12. Life expectancy at birth (years) Life expectancy at birth (years) About 50 Highgate residents die Since 2002-06, life expectancy has Cancer is the main cause of each year2009-11. -

Etrvscan • Demonstrating the 7

DEVELOPMENT OF SERIF-LESS TYPE — TIMELINE SSTUVVW XYWUZa aSWbV ZSa cVUdcW ecYX IUfgh, RYiVcU MSgWV, f jcYXSaSWk Image rights and references: fcbZSUVbUlVWkSWVVc, cVbVSmVa f gVUUVc nfUVn: Røùú, Nøû. 11, 1760. ecYX ZSa Italy Fig: XVWUYc fWn ecSVWn GSYmfWWS BfUUSaUf PScfWVaS. TZV IUfgSfW fcbZSUVbUoa 1. (Left) Leonardo Agostini (1686) Le Gemme Antiche Fiurate. Engraving of a ‘Magic Gem’ of serif-less cVjdUfUSYW Zfn bYXV SWbcVfaSWkgh dWnVc fUUfbpVn ecYX FcVWbZ fcbZSUVbUa letterforms. Tav. Fig.52 [83] CARAERI MAGICI in lapis lazuli. © GIA Library Additional Collections (Gemological Institute of America), in the public domain. fWn gSUVcfch bcSUSba Ye UZV fcUa UZcYdkZYdU UZV 1750a. CgfaaSbfg RYXfW Emf. XX 1. (Right) Leonardo Agostini (1593-1669). Portrait aged 63, frontispiece from Le Gemme Antiche Fiurate, 1686. © GIA fcbZSUVbUdcV fa fW SnVfg qfa iVSWk bZfggVWkVn SW efmYdc Ye rUZV GcVVpo Library Additional Collections (Gemological Institute of America), in the public domain. 2. Dempster, Thomas (1579-1625). Coke, Thomas, Earl of qSUZSW qZfU iVbfXV pWYqW fa UZV GcfVbYlRYXfW nVifUV. Leicester, and Bounarroti, Filippo (1723). De Etruria Regali, III Libri VII, nunc primum editi curante Thomas Coke. Opus postumum. Florentiæ: Cajetanus Tartinius. Written in With some disdain he writes: “My Work ‘On the Magnificence of 1616-19. Liber Tertius, Tabulæ Eugubinæ. (viewer pp.693-702). Tabular I of V. © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, digital.onb.ac.at in the public domain. Architecture of the Romans’ has been finished some time since... it consists 3. (Left) Forlivesi, Padre Giovanni Nicola (Giannicola). From the Convent of San Marco in Corneto. The Augustinian of 100 sheets of letterpress in Italian and Latin and of 50 plates, the IN DCCLVI GIAMBAISTA PIRANESI RELEASED monk’s 14 written bulletins to Anton Francesco Gori with observational drawings and decipherment of Etruscan inscriptions at Tarquinia near Corneto, from 11th May to 4th whole on Atlas paper.