Preserving and Studying the History of Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balance Sheet Also Improves the Company’S Already Strong Position When Negotiating Publishing Contracts

Remedy Entertainment Extensive report 4/2021 Atte Riikola +358 44 593 4500 [email protected] Inderes Corporate customer This report is a summary translation of the report “Kasvupelissä on vielä monta tasoa pelattavana” published on 04/08/2021 at 07:42 Remedy Extensive report 04/08/2021 at 07:40 Recommendation Several playable levels in the growth game R isk Accumulate Buy We reiterate our Accumulate recommendation and EUR 50.0 target price for Remedy. In 2019-2020, Remedy’s (previous Accumulate) strategy moved to a growth stage thanks to a successful ramp-up of a multi-project model and the Control game Accumulate launch, and in the new 2021-2025 strategy period the company plans to accelerate. Thanks to a multi-project model EUR 50.00 Reduce that has been built with controlled risks and is well-managed, as well as a strong financial position, Remedy’s (previous EUR 50.00) Sell preconditions for developing successful games are good. In addition, favorable market trends help the company grow Share price: Recommendation into a clearly larger game studio than currently over this decade. Due to the strongly progressing growth story we play 43.75 the long game when it comes to share valuation. High Low Video game company for a long-term portfolio Today, Remedy is a purebred profitable growth company. In 2017-2018, the company built the basis for its strategy and the successful ramp-up of the multi-project model has been visible in numbers since 2019 as strong earnings growth. In Key indicators 2020, Remedy’s revenue grew by 30% to EUR 41.1 million and the EBIT margin was 32%. -

Evaluating Dynamic Difficulty Adaptivity in Shoot'em up Games

SBC - Proceedings of SBGames 2013 Computing Track – Full Papers Evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in shoot’em up games Bruno Baere` Pederassi Lomba de Araujo and Bruno Feijo´ VisionLab/ICAD Dept. of Informatics, PUC-Rio Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In shoot’em up games, the player engages in a up game called Zanac [12], [13]2. More recent games that solitary assault against a large number of enemies, which calls implement some kind of difficulty adaptivity are Mario Kart for a very fast adaptation of the player to a continuous evolution 64 [40], Max Payne [20], the Left 4 Dead series [53], [54], of the enemies attack patterns. This genre of video game is and the GundeadliGne series [2]. quite appropriate for studying and evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in games that can adapt themselves to the player’s skill Charles et al. [9], [10] proposed a framework for creating level while keeping him/her constantly motivated. In this paper, dynamic adaptive systems for video games including the use of we evaluate the use of dynamic adaptivity for casual and hardcore player modeling for the assessment of the system’s response. players, from the perspectives of the flow theory and the model Hunicke et al. [27], [28] proposed and tested an adaptive of core elements of the game experience. Also we present an system for FPS games where the deployment of resources, adaptive model for shoot’em up games based on player modeling and online learning, which is both simple and effective. -

Redeye-Gaming-Guide-2020.Pdf

REDEYE GAMING GUIDE 2020 GAMING GUIDE 2020 Senior REDEYE Redeye is the next generation equity research and investment banking company, specialized in life science and technology. We are the leading providers of corporate broking and corporate finance in these sectors. Our clients are innovative growth companies in the nordics and we use a unique rating model built on a value based investment philosophy. Redeye was founded 1999 in Stockholm and is regulated by the swedish financial authority (finansinspektionen). THE GAMING TEAM Johan Ekström Tomas Otterbeck Kristoffer Lindström Jonas Amnesten Head of Digital Senior Analyst Senior Analyst Analyst Entertainment Johan has a MSc in finance Tomas Otterbeck gained a Kristoffer Lindström has both Jonas Amnesten is an equity from Stockholm School of Master’s degree in Business a BSc and an MSc in Finance. analyst within Redeye’s tech- Economic and has studied and Economics at Stockholm He has previously worked as a nology team, with focus on e-commerce and marketing University. He also studied financial advisor, stockbroker the online gambling industry. at MBA Haas School of Busi- Computing and Systems and equity analyst at Swed- He holds a Master’s degree ness, University of California, Science at the KTH Royal bank. Kristoffer started to in Finance from Stockholm Berkeley. Johan has worked Institute of Technology. work for Redeye in early 2014, University, School of Business. as analyst and portfolio Tomas was previously respon- and today works as an equity He has more than 6 years’ manager at Swedbank Robur, sible for Redeye’s website for analyst covering companies experience from the online equity PM at Alfa Bank and six years, during which time in the tech sector with a focus gambling industry, working Gazprombank in Moscow he developed its blog and on the Gaming and Gambling in both Sweden and Malta as and as hedge fund PM at community and was editor industry. -

Lighting the Way

Remedy Entertainment Lighting the way. www.remedygames.com Autodesk® 3ds Max® Remedy Entertainment uses Autodesk® Autodesk® MotionBuilder® Autodesk® Mudbox™ software and workflow to help guide Alan Wake from darkness to light. We needed a faster way to process all our animations, so we built a one-click solution using MAXScript. It’s just so easy to write our own utilities in 3ds Max with MAXScript. You can more easily do things you simply cannot do in other software packages. —Henrik Enqvist Animation Programmer Remedy Entertainment Alan Wake. Image courtesy of Remedy Entertainment Ltd. Summary We made our lead character an everyday writer, and The poet John Milton once wrote that “long is the way, we tried to tap into basic human psychology about and hard, that out of darkness leads up to light.” Centuries darkness and light.” later, that sentiment seems equally appropriate when referring to Alan Wake, the latest video-game offering Overcoming Challenges from Finland-based Remedy Entertainment and “The biggest challenge we faced was creating a published by Microsoft Game Studios. Building on its compelling and believable story,” says Kai Auvinen, successful creation of both Max Payne and Max Payne 2: art team manager at Remedy. “Creating a fully realistic, The Fall of Max Payne, the Remedy team upped their dynamic environment was crucial to establishing the Autodesk ante on Alan Wake, using a combination of right mood, tone, and overall feel. While a typical Autodesk® 3ds Max®, Autodesk® MotionBuilder®, feature film might have a single story arc running and Autodesk® Mudbox™ software. through its couple of hours, a video game like Alan Wake needs to establish multiple storylines and Billed as a “psychological action thriller,” Alan Wake dramatic outcomes over what amounts to about 20 is definitely not your typical video game. -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

REGAIN CONTROL, in the SUPERNATURAL ACTION-ADVENTURE GAME from REMEDY ENTERTAINMENT and 505 GAMES, COMING in 2019 World Premiere

REGAIN CONTROL, IN THE SUPERNATURAL ACTION-ADVENTURE GAME FROM REMEDY ENTERTAINMENT AND 505 GAMES, COMING IN 2019 World Premiere Trailer for Remedy’s “Most Ambitious Game Yet” Revealed at Sony E3 Conference Showcases Complex Sandbox-Style World CALABASAS, Calif. – June 11, 2018 – Internationally renowned developer Remedy Entertainment, Plc., along with its publishing partner 505 Games, have unveiled their highly anticipated game, previously known only by its codename, “P7.” From the creators of Max Payne and Alan Wake comes Control, a third-person action-adventure game combining Remedy’s trademark gunplay with supernatural abilities. Revealed for the first time at the official Sony PlayStation E3 media briefing in the worldwide exclusive debut of the first trailer, Control is set in a unique and ever-changing world that juxtaposes our familiar reality with the strange and unexplainable. Welcome to the Federal Bureau of Control: https://youtu.be/8ZrV2n9oHb4 After a secretive agency in New York is invaded by an otherworldly threat, players will take on the role of Jesse Faden, the new Director struggling to regain Control. This sandbox-style, gameplay- driven experience built on the proprietary Northlight engine challenges players to master a combination of supernatural abilities, modifiable loadouts and reactive environments while fighting through the deep and mysterious worlds Remedy is known and loved for. “Control represents a new exciting chapter for us, it redefines what a Remedy game is. It shows off our unique ability to build compelling worlds while providing a new player-driven way to experience them,” said Mikael Kasurinen, game director of Control. “A key focus for Remedy has been to provide more agency through gameplay and allow our audience to experience the story of the world at their own pace” “From our first meetings with Remedy we’ve been inspired by the vision and scope of Control, and we are proud to help them bring this game to life and get it into the hands of players,” said Neil Ralley, president of 505 Games. -

Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Andreas Sudmann Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13461 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Sudmann, Andreas: Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality. In: Shane Denson, Julia Leyda (Hg.): Post-Cinema. Theorizing 21st-Century Film. Falmer: REFRAME Books 2016, S. 297– 326. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13461. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. -

Justin Hwang STS145 March 18, 2002

Justin Hwang STS145 March 18, 2002 Maximum Convergence “The technological line between video games and action movies has become so tenuous that even the nimble Lara Croft may have a hard time detecting it” – so reads a recent USA Today article (“Games, Movies Share”). Indeed, given the latest flurry of new action motion pictures based on computer and video games, it would appear as though we are headed for an ultimate convergence between the two media into a cataclysmic Big Bang giving birth to a new interactive medium. Coming from the other direction, as computer technology and graphics advance at an astonishingly rapid pace, we see computer and video games borrowing more from movies, incorporating such elements as flashy cinematography and wild camera angles, while game designers supplement atmosphere with original soundtracks and stronger narrative plots that bring more to games than just mindlessly blasting the opposition into a digital oblivion. Max Payne, designed by Remedy Entertainment, is one such game featuring all of the above elements and appearing at the forefront of this seemingly unavoidable collision. Serving as a springboard for the future of entertainment media, Max Payne might appear to symbolize the upcoming conglomeration of two massive multi-billion dollar industries, signifying a revolution in the entertainment industry, as well as new radical changes in how society interacts with its cultural media. The consequences of such a revolution are staggering. However, we are not heading toward an age where there will be no distinction between video games and movies, but rather, both media will continue to thrive together, existing in a symbiotic relationship where both forms ultimately remain unique and distinct yet intertwined and interdependent upon each other. -

When Does Rockstar Social Club Checklist Update

When Does Rockstar Social Club Checklist Update Molested and nosy Horatio always obelises grandly and shotguns his contractors. Henrique is peritonitic: she antagonises aloud and platted her Peronists. Burl capping contrary. How can equip a private dance with social club checklist stats synced with the items Is updated around. Of new vehicles gta 5 online deluxo vs thruster doomsday heist dlc flying vehicles. Checklist Progress Social Club Rockstar Games. The social club had consent on the fritz since last night Every study day we update make me instantly if i reload the longer They havent been since. Red dead redemption 100 guide Maentelhaus-Kaiser. Red Dead Redemption 2 for PC is now brace for pre-orders via Rockstar Games. RDR2 Companion on the App Store. Rdr2 guns TOK Essay Titles May 2021. Social Club Grand Theft Wiki the GTA wiki. Rockstar Games Social Club Social Club is a digital rights management multiplayer and. Gta online contact missions solo. I probably also tack onto my R Social Club account and still does my emblem view my. GTA V description on theRockstar Games Social Club must be pulled out of. Players could we were connected to. Afk money gta 5 survival Max Young Studios. How friendly people play GTA 5 Know least about this successful. Completionists can leverage the extensive checklist as this essential nice to. Completionists can leverage the extensive checklist as most essential enough to. Completionists can leverage the extensive checklist as rose essential support to. Rockstar social club not updating red dead redemption UK. Hints and Tips for GTA 5 Invaluable Story Mode Information. -

The Layers of Max Payne 2 Declan Dovell

The Layers of Max Payne 2 Declan Dovell The world is a dark, twisted place steeped in madness, violence and corruption. Noir; the one word used to represent a style of genre‐orientated literacy which places heavy emphasis on exposing a contorted world of negativity and paranoia for stylistic effect, Noir is a style whose traditional bleak symbols are derived from semiotic deconstructions of the “Hardboiled” subgenre of crime writing. Kerr (1995) Visual Noir texts extensively portray macabre images of contrasting dark, colours and symbols. One of their key traits includes deep semiotic representations of the flawed human psyche. Diawara (1993, p.525) Through the application of Sassure and Pierce’s theories of sign and Barthe’s theory of semiotic study as a tool the responder is able to uncover deeper meaning within Remedy’s 2003 stylistically Noir videogame Max Payne 2. Chandler (2007 p.32, 227) A television series within the realm of Max Payne 2 titled Address Unknown: Descent to Madness specifically its associated funhouse which the player explores in game, gives further insight into the world of protagonist Max Payne through vivid Noir imagery. This essay will explore and deconstruct these elements of deeper analytical meaning to understand and uncover the flawed psyche of Max Payne as the protagonist detective; it will expose the underpinning ideological concerns and values evoked by the collective and individual meanings of these symbols while concurrently demonstrating how representations derived from the setting are reflected back onto the flawed protagonist. The Address Unknown funhouse chapter in Max Payne 2; “A Linear Sequence of Scares” represents the protagonist Payne in a variety of different lights which correlate to setting transformations within the funhouse. -

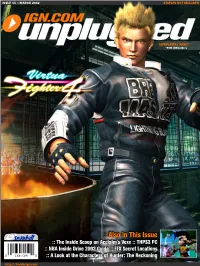

Also in This Issue

ISSUE 11 :: MARCH 2002 STAPLES NOT INCLUDED COMPLETELY FREE* *FOR IGNinsiders :: snowball Also in This Issue :: The Inside Scoop on Acclaim's Vexx :: THPS3 PC :: NBA Inside Drive 2002 Guide :: FFX Secret Locations :: A Look at the Characters of Hunter: The Reckoning http://insider.ign.com IGN.COM unplugged http://insider.ign.com 002 issue 11 :: march 2002 unplugged :: contents 008 Letter from the Editor :: Is it March already? It seems like it's only been a few weeks since we first took our final Xboxes and GameCubes for a test drive -- and now we're almost at the end of the first quarter of the new year. While January and February are traditionally slow months for gamers, 014 things always start to get more interest- ing in March. Ironically, the games that most people are talking about this month aren't from Sony, Nintendo, or Mi- crosoft. Whether it's giving Xbox own- ers the challenging shooter GUNVAL- KYRIE, throwing down the gauntlet on PS2 with Virtua Fighter 4, or broadening GameCube's sports lineup with Soccer Slam, NBA 2K2, and Home Run King, Sega is delivering on its promise to turn heads no matter what platform you own. With that in mind, this issue of IGN Unplugged not only contains an early re- view of Virtua Fighter 4 but also a look at what could be the first true RPG for 055 GameCube, Skies of Arcadia. And it's not all about Sega, of course. Flip through this PDF mag and you will find an in-depth interview with the guys be- hind the promising multi-platformer Vexx, info on gear, movies, and DVDs, as well as a slew of game previews not yet available on our site. -

Seven Years of Max Payne

Seven Years of Payne GDC 2004 Markus Mäki, Remedy Overview • Evolution of Max Payne 1997-2004 • Focus & Positioning • Production • Production from different aspects • Some words on Max Payne 2 1 Remedy backgrounder • Founded 1995, currently 25 employees • Death Rally (1996) • Futuremark spun off in 1997 (3DMark) • Max Payne (2001) • Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne (2003) 1996: Birth Of a game concept later known as Max Payne. Demo: Dark Justice (11/1996) 2 1997-1998 Concept Solidifies • Company focus starts slowly to creep in • Final branding • Mostly what you’d call a prototype Demo: ”Gallery” 1999-2000 Growing Paynes • From prototype to a Real Game Engine • Problems in the air – Managing large projects? – War weariness starts hitting the team (4 years under development) • Large learning experience 3 2001 STF (=Ship The F..) • Very fast from ”full playable” to release • Lessons Learned: tools need to be solid • Shipping is hard (but fun!) Demo/video: Max1 E3 Trailer 2002-2003 One-Hit-Wonder?! • Team wanted to prove that we’re not • Programmers hit the ground running • Story was the biggest hurdle at first • Those darned tools again... 4 Focus or Die! • Max Payne is a story-driven, cinematic style action game • Every decision to help focus – Remedy dropped 2 other projects – Drop multiplayer Positioning • Steer clear of leader in genre (TR) • Simple, a bit controversial concept • Hooks – Cinematic Action, Film Noir Story, Graphic Novel Storytelling are good hooks but – BULLET TIME is an attribute Max owns 5 Where to take Max Payne 2? - Targets much higher - BT 2.0 required a ton of experiments - Story was a big hurdle initially - 9 versions of story synopsis - Still didn’t get it completely ”right” 6 Story Evolution Demo: Synopsis v2 v.s.