Do Modern Stories Need Interactivity? A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balance Sheet Also Improves the Company’S Already Strong Position When Negotiating Publishing Contracts

Remedy Entertainment Extensive report 4/2021 Atte Riikola +358 44 593 4500 [email protected] Inderes Corporate customer This report is a summary translation of the report “Kasvupelissä on vielä monta tasoa pelattavana” published on 04/08/2021 at 07:42 Remedy Extensive report 04/08/2021 at 07:40 Recommendation Several playable levels in the growth game R isk Accumulate Buy We reiterate our Accumulate recommendation and EUR 50.0 target price for Remedy. In 2019-2020, Remedy’s (previous Accumulate) strategy moved to a growth stage thanks to a successful ramp-up of a multi-project model and the Control game Accumulate launch, and in the new 2021-2025 strategy period the company plans to accelerate. Thanks to a multi-project model EUR 50.00 Reduce that has been built with controlled risks and is well-managed, as well as a strong financial position, Remedy’s (previous EUR 50.00) Sell preconditions for developing successful games are good. In addition, favorable market trends help the company grow Share price: Recommendation into a clearly larger game studio than currently over this decade. Due to the strongly progressing growth story we play 43.75 the long game when it comes to share valuation. High Low Video game company for a long-term portfolio Today, Remedy is a purebred profitable growth company. In 2017-2018, the company built the basis for its strategy and the successful ramp-up of the multi-project model has been visible in numbers since 2019 as strong earnings growth. In Key indicators 2020, Remedy’s revenue grew by 30% to EUR 41.1 million and the EBIT margin was 32%. -

Contributors

gems_ch001_fm.qxp 2/23/2004 11:13 AM Page xxxiii Contributors Curtis Beeson, NVIDIA Curtis Beeson moved from SGI to NVIDIA’s Demo Team more than five years ago; he focuses on the art path, the object model, and the DirectX ren- derer of the NVIDIA demo engine. He began working in 3D while attending Carnegie Mellon University, where he generated environments for playback on head-mounted displays at resolutions that left users legally blind. Curtis spe- cializes in the art path and object model of the NVIDIA Demo Team’s scene- graph API—while fighting the urge to succumb to the dark offerings of management in marketing. Kevin Bjorke, NVIDIA Kevin Bjorke works in the Developer Technology group developing and promoting next-generation art tools and entertainments, with a particular eye toward the possibilities inherent in programmable shading hardware. Before joining NVIDIA, he worked extensively in the film, television, and game industries, supervising development and imagery for Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within and The Animatrix; performing numerous technical director and layout animation duties on Toy Story and A Bug’s Life; developing games on just about every commercial platform; producing theme park rides; animating too many TV com- mercials; and booking daytime TV talk shows. He attended several colleges, eventually graduat- ing from the California Institute of the Arts film school. Kevin has been a regular speaker at SIGGRAPH, GDC, and similar events for the past decade. Rod Bogart, Industrial Light & Magic Rod Bogart came to Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) in 1995 after spend- ing three years as a software engineer at Pacific Data Images. -

Evaluating Dynamic Difficulty Adaptivity in Shoot'em up Games

SBC - Proceedings of SBGames 2013 Computing Track – Full Papers Evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in shoot’em up games Bruno Baere` Pederassi Lomba de Araujo and Bruno Feijo´ VisionLab/ICAD Dept. of Informatics, PUC-Rio Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In shoot’em up games, the player engages in a up game called Zanac [12], [13]2. More recent games that solitary assault against a large number of enemies, which calls implement some kind of difficulty adaptivity are Mario Kart for a very fast adaptation of the player to a continuous evolution 64 [40], Max Payne [20], the Left 4 Dead series [53], [54], of the enemies attack patterns. This genre of video game is and the GundeadliGne series [2]. quite appropriate for studying and evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in games that can adapt themselves to the player’s skill Charles et al. [9], [10] proposed a framework for creating level while keeping him/her constantly motivated. In this paper, dynamic adaptive systems for video games including the use of we evaluate the use of dynamic adaptivity for casual and hardcore player modeling for the assessment of the system’s response. players, from the perspectives of the flow theory and the model Hunicke et al. [27], [28] proposed and tested an adaptive of core elements of the game experience. Also we present an system for FPS games where the deployment of resources, adaptive model for shoot’em up games based on player modeling and online learning, which is both simple and effective. -

Redeye-Gaming-Guide-2020.Pdf

REDEYE GAMING GUIDE 2020 GAMING GUIDE 2020 Senior REDEYE Redeye is the next generation equity research and investment banking company, specialized in life science and technology. We are the leading providers of corporate broking and corporate finance in these sectors. Our clients are innovative growth companies in the nordics and we use a unique rating model built on a value based investment philosophy. Redeye was founded 1999 in Stockholm and is regulated by the swedish financial authority (finansinspektionen). THE GAMING TEAM Johan Ekström Tomas Otterbeck Kristoffer Lindström Jonas Amnesten Head of Digital Senior Analyst Senior Analyst Analyst Entertainment Johan has a MSc in finance Tomas Otterbeck gained a Kristoffer Lindström has both Jonas Amnesten is an equity from Stockholm School of Master’s degree in Business a BSc and an MSc in Finance. analyst within Redeye’s tech- Economic and has studied and Economics at Stockholm He has previously worked as a nology team, with focus on e-commerce and marketing University. He also studied financial advisor, stockbroker the online gambling industry. at MBA Haas School of Busi- Computing and Systems and equity analyst at Swed- He holds a Master’s degree ness, University of California, Science at the KTH Royal bank. Kristoffer started to in Finance from Stockholm Berkeley. Johan has worked Institute of Technology. work for Redeye in early 2014, University, School of Business. as analyst and portfolio Tomas was previously respon- and today works as an equity He has more than 6 years’ manager at Swedbank Robur, sible for Redeye’s website for analyst covering companies experience from the online equity PM at Alfa Bank and six years, during which time in the tech sector with a focus gambling industry, working Gazprombank in Moscow he developed its blog and on the Gaming and Gambling in both Sweden and Malta as and as hedge fund PM at community and was editor industry. -

Lighting the Way

Remedy Entertainment Lighting the way. www.remedygames.com Autodesk® 3ds Max® Remedy Entertainment uses Autodesk® Autodesk® MotionBuilder® Autodesk® Mudbox™ software and workflow to help guide Alan Wake from darkness to light. We needed a faster way to process all our animations, so we built a one-click solution using MAXScript. It’s just so easy to write our own utilities in 3ds Max with MAXScript. You can more easily do things you simply cannot do in other software packages. —Henrik Enqvist Animation Programmer Remedy Entertainment Alan Wake. Image courtesy of Remedy Entertainment Ltd. Summary We made our lead character an everyday writer, and The poet John Milton once wrote that “long is the way, we tried to tap into basic human psychology about and hard, that out of darkness leads up to light.” Centuries darkness and light.” later, that sentiment seems equally appropriate when referring to Alan Wake, the latest video-game offering Overcoming Challenges from Finland-based Remedy Entertainment and “The biggest challenge we faced was creating a published by Microsoft Game Studios. Building on its compelling and believable story,” says Kai Auvinen, successful creation of both Max Payne and Max Payne 2: art team manager at Remedy. “Creating a fully realistic, The Fall of Max Payne, the Remedy team upped their dynamic environment was crucial to establishing the Autodesk ante on Alan Wake, using a combination of right mood, tone, and overall feel. While a typical Autodesk® 3ds Max®, Autodesk® MotionBuilder®, feature film might have a single story arc running and Autodesk® Mudbox™ software. through its couple of hours, a video game like Alan Wake needs to establish multiple storylines and Billed as a “psychological action thriller,” Alan Wake dramatic outcomes over what amounts to about 20 is definitely not your typical video game. -

Gta San Andreas Dan Houserrel, a Játék Producerével Beszélgettünk

THE LEGEND OF SHERWOOD KIADÁS DVD GOTHIC ÉS ROBIN HOOD TELJES JÁTÉKOK A DVD-N! G Európa legolvasottabb gamer magazinja www.gamestar.hu 2004/12 12 2004/12 Ára: 1896 Ft GameStar – Európa legolvasottabb gamer magazinja – Teljes játék: Gothic, Robin Hood: The Legend of Sherwood G GameStar – Európa – Teljes legolvasottabb gamer magazinja DUPLA DVD-VEL! a m nyi HALF-LIFE 2 MAGYARÍTÁS + VIDEÓ e CD S VIDEOINTERJÚ t tartalom PRINCE OF PERSIA 2 a r 14 – E u r ó p a l e g o l v a s o t t a VVAMPIREAMPIRE b b g TTHEHE MMASQUERADE:ASQUERADE: BBLOODLINESLOODLINES a m e 22004004 LLEGJOBBEGJOBB SZEREPJÁTÉKASZEREPJÁTÉKA MMEGÉRKEZETT!EGÉRKEZETT! r m a YI „MIN g N O DE a S N z C T i n Á B j R E a TELJES2 JÁTÉK CCHRONICLESHRONICLES OOFF A L – K E T DUPLA DVD - 15 JÁTÉKDEMÓ ” e ! l j e 2,5 MILLIÓS ELŐFIZETŐI AKCIÓ s j á t é RRIDDICKIDDICK 140 OLDAL k : G o t h i c , PPRINCERINCE OOFF PPERSIAERSIA 2 R o b i n H BBATTLEATTLE FORFOR MIDDLEMIDDLE EARTHEARTH o o d : T h e L e g e n d o f S h e r w o o d HHALOALO 2 A NNAGYFŐNÖKAGYFŐNÖK VVISSZATÉRISSZATÉR – PPC-REC-RE IIS!S! Játéktesztek: Men of Valor, Cross Racing Championship, NBA 2005, Tribes: Vengeance, Leisure Suit Larry Mélyvíz: Konfigurációk karácsonyra, A legújabb GeForce-ok, Megoldások rendszerösszeomlás esetére Játékdemók: 15 db, köztük BloodRayne 2, Cross Racing Championship, Flatout, Pro Evolution Soccer 4 GGSEzust_200412.inddSEzust_200412.indd 1 112/1/20042/1/2004 44:32:48:32:48 PPMM TARTALOM Bemelegítés Gyorskereső CD-tartalom 6 FÓKUSZ DVD-tartalom 7 Atlantis: Evolution B 92 Teljes játékok: Robin Hood, Gothic 8 Chronicles of Riddick E 38 8 Cross Racing Championship B T 82 CSI: Miami B 86 F.E.A.R. -

2014/9/18あ 出展予定タイトル ※50音順あ

東京ゲームショウ2014 2014/9/18あ 出展予定タイトル ※50音順あ 対応プラットフォーム ニ ニ W W P P P P X X S P P i A そ フ そ 出展タイトル ン ン i i S S S S b b t C C O n の ィ の テ テ i i 3 4 P o o e ブ S d 他 ー 他 発売日 出展社名 ン ン V x x a ラ r ス チ オンライン 価格 ジャンル または ド ド U i 3 m ウ o マ ャ 対応 (※注釈) (展示コーナー) 配信日 ー ー t 6 O ザ i ー ー 英語 3 D a 0 n ゲ d ト フ 日本語 D S e ー フ ォ (またはローマ字表記) S ム ォ ン ン ア ギルティギア イグザード サイン GUILTY GEAR Xrd -SIGN- アクション 2014年12月4日発売予定 ○ ○ ○ 予価6980円(DL版5502円、PS4限定版9980円) アークシステムワークス ダウンタウン熱血行進曲 それゆけ大運動 DOWNTOWN NEKKETSU KOUSHINKYOKU アクション 2014年冬発売予定 予価4800円 (一般展示/1-S1) 会 ~オールスタースペシャル~ SOREYUKE DAIUNDOUKAI ALL STAR ○ ○ SPECIAL エクスブレイズ ロスト:メモリーズ XBLAZE LOST:MEMORIES アドベンチャー 2015年発売予定 ○ ○ 未定 ラブコネクト LOVE CONNECT シミュレーション 発売中 ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) アール・インフィニティ 再愛メルヘン~ロッテフォレストの童話~ a fairy tale of the two meant to meet again シミュレーション 2015年春配信予定 基本無料(アイテム課金) ○ ○ ○ (ロマンスゲームコーナー/2-C4) ~Lotte Forest~ JOD-ジュエル オブ デザイア- JOD-jewel of desire- シミュレーション 配信中 ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) 貴方だけのオリジナルスマホケース (グッズ) (物販コーナーで販売) 3000円 ※その場でプリントします Akiba Factory ○ (スマートフォン・アクセサリー・ お好きな文字がプリントできるスマホケース (グッズ) (物販コーナーで販売) 2000円 ※その場でプリントします コレクション 2014/7-N11) ○ アヴァベルオンライン AVABEL ONLINE ロールプレイング・アクション 配信中 ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) イザナギオンライン IZANAGI ONLINE ロールプレイング・アクション 配信中 ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) オルクスオンライン Aurcus Online ロールプレイング・アクション 配信中 ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) セレスアルカオンライン CelesArca Online ロールプレイング 配信中 ○ ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) イルーナ戦記オンライン IRUNA ONLINE ロールプレイング 配信中 ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) アソビモ ステラセプトオンライン Stellacept Online ロールプレイング 配信中 ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) (一般展示/4-C22) エリシアオンライン Ellicia Online ロールプレイング 配信中 ○ ○ ○ ○ 基本無料(アイテム課金) トーラムオンライン Toram Online -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

364 Gaminguistics: Proposing a Framework on The

Journal of Social Studies Education Research Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi 2019:10 (3),364-386 www.jsser.org Gaminguistics: Proposing a Framework on the Communication of Video Game Avatars Giyoto Giyoto1, SF. Luthfie Arguby Purnomo2, Lilik Untari3, SF. Lukfianka Sanjaya Purnama4 & Nur Asiyah5 Abstract This study attempts to construct a communication framework of video game avatars. Employing Aarseth’s textonomy, Rehak’s avatar’s life cycle, and Lury’s prosthetic culture avatar’s theories as the basis of analysis on fifty-five purposively selected games, this study proposes ACTION (Avatars, Communicators, Transmissions, Instruments, Orientations and Navigations). Avatars, borrowing Aarseth’s terms, are classifiable into interpretive, explorative, configurative, and textonic with four systems and sub classifications for each type. Communicators, referring to the participants involved in the communication with the avatars and their relationship, are classifiable into unipolar, bipolar, tripolar, quadripolar, and pentapolar. Transmissions, the ways in which communication is transmitted, are classifiable into restrictive verbal and restrictive non-verbal. Instruments, the graphical embodiment of communications, are realized into dialogue boxes, non-dialogue boxes, logs, expressions, movements and emoticons. Orientations, the methods the game spatiality employs to direct the movement of the avatars, are classifiable into dictative and non-dictative. Navigations, the strategies avatars perform regarding with the information saving system of the games, are classifiable into experimental and non-experimental. Departing from this ACTION, analysts are able to employ this formula as an approach to reveal how the avatars utilize their own ‘linguistics’ to communicate, out of the linguistics benefited by humans. Keywords: framework of communication, game avatars, game studies, video games, prosthetic culture. -

Cheats Gothik

Cheats gothik click here to download For Gothic II: Gold Edition on the PC, GameFAQs has 44 cheat codes and secrets. This page contains Gothic Codes for PC called "God Mode and Full Health" and has been posted or updated on Jan 18, by galvatron If you do this right you will get Marvin in the upper left hand corner. Type (cheat god) for god mode. Get all the inside info, cheats, hacks, codes, walkthroughs for Gothic 3 on GameSpot. The best place to get cheats, codes, cheat codes, walkthrough, guide, FAQ, unlockables, tricks, and secrets for Gothic 3 for PC. Suchen Sie darin die Zeile testmode=0 und ändern Sie diese in testmode=1, um die Konsole und somit die Cheats zu aktivieren. Um den Cheatmodus in Gothic II zu aktivieren müsst ihr wie auch schon im ersten das Hier eine Auflistung einiger ausgewählter Cheats, die Kermit.d für uns Befehl: Auswirkung. Bevor man Cheats im Spiel benutzen kann, muss man zuerst den Marvin-Modus (Testmodus) Dazu öffnet man im Gothic 3 Verzeichnis die Datei "www.doorway.ru". World of Gothic - the biggest fansite about the RPG-series Gothic from the Activate the cheat/test mode in the game and use give or spawn and the insert code. Hi Leutz, heute mach ich es kurz. Kennt einer den Cheat für Waffenbündel? Gruß Mahone. Gothic 2 Cheats und Tipps: Komplettlösung, Cheats, Trainer, Einsteiger-Guide, Charakterentwicklung, Diebesgilde, Geheime Orte und 6 weitere Themen. Hallo, ich wollte mal fragen wie ich bei dem CP Gold erhöhen kann also cheaten weil mit Cheat Engine bzw ArtMoney funkt es nicht. -

PRGE Nes List.Xlsx

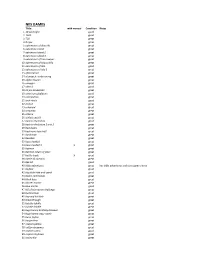

NES GAMES Tittle with manual Condition Notes 1 10 yard fight good 2 1943 great 3 720 great 4 8 eyes great 5 adventures of dino riki great 6 adventure island great 7 adventure island 2 great 8 adventure island 3 great 9 adventures of tom sawyer great 10 adventures of bayou billy great 11 adventures of lolo good 12 adventures of lolo 2 great 13 after burner great 14 al unser jr. turbo racing great 15 alpha mission great 16 amagon great 17 alien 3 good 18 all pro basketball great 19 american gladiators good 20 anticipation great 21 arch rivals good 22 archon great 23 arkanoid great 24 astyanax great 25 athena great 26 athletic world great 27 back to the future good 28 back to the future 2 and 3 great 29 bad dudes great 30 bad news base ball great 31 bards tale great 32 baseball great 33 bases loaded great 34 bases loaded 3 X great 35 batman great 36 batman return of joker great 37 battle toads X great 38 battle of olympus great 39 bee 52 good 40 bible adventures great has bible adventures exclusive game sleeve 41 bigfoot great 42 big birds hide and speak good 43 bionic commando great 44 black bass great 45 blaster master great 46 blue marlin good 47 bill elliots nascar challenge great 48 bomberman great 49 boy and his blob great 50 breakthrough great 51 bubble bobble great 52 bubble bobble great 53 bugs bunny birthday blowout great 54 bugs bunny crazy castle great 55 burai fighter great 56 burgertime great 57 caesars palace great 58 california games great 59 captain comic good 60 captain skyhawk great 61 casino kid great 62 castle of dragon great 63 castlvania great 64 castlvania 2 great 65 castlvania 3 great 66 caveman games great 67 championship bowling great 68 chessmaster great 69 chip n dale great 70 city connection great 71 clash at demonhead great 72 concentration poor game is faded and has tears to front label (tested) 73 cobra command great 74 cobra triangle great 75 commando great 76 conquest of crystal palace great 77 contra great 78 cybernoid great 79 crystal mines X great black cartridge. -

Download Full Press Release (Pdf)

PRESS RELEASE Essen/Munich, Germany, August 10, 2011 PR Contact: Deep Silver Martin Metzler A division of Koch Media GmbH Tel: +49 89 24245-123 Lochhamerstr. 9 Fax: +49 89 24245-3 123 82152 Planegg/Munich [email protected] Germany Yo-ho, yo-ho - pirates find new anchorage on Risen 2™ website Expanded online presence with extensive information on the role-playing game, including a brand new ingame trailer As Deep Silver and Piranha Bytes announced today, the expanded website for the RPG Risen 2: Dark Waters is now online. At www.risen2.com, adventurers now receive even deeper insights into the exciting world of the long-awaited sequel to the best-selling RPG Risen™. Apart from new details about the story and the continents, the Risen 2 website also provides background information on the nameless hero. In the coming months, the "World" and "Characters" areas will be further expanded, and descriptions of the game's different creatures will be added. Fans will, of course, also find the latest news at www.risen2.com, as well as an interesting FAQ section, screenshots, wallpapers, and the downloadable CGI video. Moreover, visitors to the website can register for the newsletter and share their impressions with other players on the message boards or via Facebook. Brand new on the official Risen 2 website is the first ingame trailer for the game which can be watched on the site. In Risen 2: Dark Waters, the Inquisition dispatches the hero to seek a remedy against the monstrous sea creatures that are interfering with the shipping lines, thus cutting off the islands' supplies.