Dr. House, Meet Doctor Dolittle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECU® Storybook Theatre Presents

ECU® Storybook Theatre presents ADA Accommodation: 252-737-1018 | [email protected] theatredance.ecu.edu | 252-328-6829 ECU® Storybook Theatre presents Dramatized by Olga Fricker. Based on the book by Hugh Lofting Director Patch Clark Music Director Monica Edwards Stage Manager Dashay Williams Scenic Deisgn Connor Gerney Lighting Design Stuart Lannon Costume Design Monica Edwards Sound Deisgn Riley Yates Storybook Theatre's Production of Doctor Dolittle is dedicated in loving memory to Ann Rhem Schwarzmann, Patron of ECU Storybook Theatre and School of Theatre and Dance ©2020. This livestream or video recording was produced by special arrangement with Dramatic Publishing Company. All rights reserved. This performance is authorized for private, in-home use only. By viewing the livestream or video recording, you agree not to authorize or permit the livestream or recording to be downloaded, copied, distributed, broadcast, telecast or otherwise exploited, in whole or in part, in any media now known or hereafter developed. WARNING: Federal law provides severe civil and criminal penalties for the unauthorized reproduction, distribution or exhibition of copyrighted motion pictures, videotapes or videodiscs. Criminal copyright infringement is investigated by the FBI and may constitute a felony with a maximum penalty of up to five years in prison and/or a $250,000.00 fine. From the Director Greetings, everyone! It was my distinct pleasure to direct ECU Storybook Theatre’s production of Doctor Dolittle, and even though under the most challenging of circumstances during a pandemic year, when cast members had to faithfully practice socially distancing, washing of hands and the wearing of masks, we persevered. -

Victorian Vets: Woeful Reputations

Vet Times The website for the veterinary profession https://www.vettimes.co.uk Victorian vets: woeful reputations Author : Pippa Elliott Categories : Vets Date : September 12, 2011 Pippa Elliott looks back to a time where the profession was held in much lower regard than it is now “YES, there are plenty [of vets],” said Polynesia, ’but none of them any good at all,” by Hugh Lofting in The Story of Doctor Dolittle. Times change Perhaps there was a golden age, probably around the time of James Herriot, when people trusted and respected the veterinary profession. However, now there are investigative journalists, the internet and clients coming in telling you, the professional, the treatment they have researched and want their pets to have. We live in times of accountability to the public, and helping them make informed decisions. However, perhaps taking examples from history, change has been a long time coming. Looking back at the veterinary profession’s earliest reputation, it seems it started from a pretty low base. Take, for example, this passage from Hugh Lofting’s popular novel The Story of Doctor Dolittle from 1920. It says: “It happened one day that the doctor was sitting in his kitchen talking with the cat’s meat 1 / 3 man, who had come to see him with a stomach ache. “‘Why don’t you give up being a people’s doctor and be an animal doctor?’ asked the cat’s meat man. “‘But there are plenty of animal doctors,’ John Dolittle replied. “‘But you see, Doctor,’ the cat’s meat man went on, ’you know all about animals much more than what these here vets do.’ ’‘Yes, there are plenty,’ said Polynesia (the parrot), ‘but none of them any good at all.’” Only choking If we look further back to the Victorians, it seems pet owners had to be at their wits’ end to call out a vet. -

The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle (Library Edition) Hugh Lofting Kathleen Olmstead Rebecca K

2021-09-28 Classic Starts The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle (Library Edition) Hugh Lofting Kathleen Olmstead Rebecca K. Reynolds Product Details Format: CD-Audio ISBN: 9781631085611 Published: 8th Sep 2020 Publisher: Oasis Audio Dimensions: 140 x 165 x 16mm Series: Classic Starts Description Following Sterling's spectacularly successful launch of its children's classic novels (240,000 books in print to date),comes a dazzling new series: Classic Starts. The stories are unabridged and have been rewritten for younger audiences. Classic Starts treats the world's beloved tales (and children) with the respect they deserve. Doctor Dolittle is a very special vet—because he knows how to talk to the animals! So when he hears that there's a terrible sickness hurting all the monkeys in Africa, the good doctor knows he must go and help them. Soon he's off on an exciting adventure across the seas in this superb retelling of Hugh Lofting's beloved classic. Author Hugh Lofting was born in 1866 in Maidenhead, England. He trained as a civil engineer, getting his education from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Polytechnic Institute of London. He worked in Africa, the West Indies and Canada and then settled in New York to become a writer. The stories about Doctor Dolittle began as letters to his children while overseas in England during World War I, where Lofting served with the British Army. The first Doctor Dolittle book published was "The Story of Doctor Dolittle" in 1920. He wrote thirteen more, winning the Newberry Medal in 1923 for "The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle." Lofting illustrated all of the Dolittle books himself. -

The Story of Dr. Dolittle | Leveled Reader

Editors Jerry Stemach, MS, CCC-SLP Karen Erickson, PhD Center for Literacy and Disability Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Exclusively Published by Don Johnston Incorporated 26799 West Commerce Drive Volo, IL 60073 USA myreadtopia.com Copyright © 2020 Start to Finish L.L.C. Start-to-Finish and the Don Johnston logos are registered trademarks. Readtopia is a trademark of Start to Finish L.L.C. Start to Finish L.L.C. grants the rights for teachers and other educational professionals to download, print, reproduce, and distribute this book with students, or portions of it in any form, in both print and electronic formats while their subscription is active. Birds, Mammals, and Reptiles The Story of Dr. Dolittle by Hugh Lofting retold by Mary J. Chester Don Johnston Incorporated Volo, Illinois Table of Contents Chapter 1 Doctor Dolittle of Puddleby . 5 Chapter 2 An Animal Doctor . 11 Chapter 3 More Trouble with Money . 16 Chapter 4 The Great Journey . 22 Chapter 5 Polynesia and the King . 25 Chapter 6 Many Sick Animals . 31 Chapter 7 A Rare Animal . 39 Chapter 8 Prince Bumpo . 44 Chapter 9 Pirates! . 49 Chapter 10 Going Home . 56 About the Readtopia Author . 62 About the Original Author . 63 Chapter 1 5 Doctor Dolittle of Puddleby Let’s meet Doctor John Dolittle. People call him “Dr. Dolittle” for short. You can, too. 6 Dr. Dolittle lives in Puddleby, England. His house is small. He needs a bigger house. His garden is big. He needs an even bigger garden. Why? Dr. Dolittle has too many animals. -

The Story of Doctor Dolittle Hugh Lofting

The Story of Doctor Dolittle Hugh Lofting ALMA CLASSICS alma classics an imprint of alma books ltd 3 Castle Yard Richmond Surrey TW10 6TF United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com The Story of Doctor Dolittle first published in 1920 This edition first published by Alma Classics in 2018 Cover image © Susan Hellard, 2018 Extra Material © Alma Books Ltd Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-745-1 All the pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or pre sumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge their copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents The Story of Doctor Dolittle 1 Notes 104 Extra Material for Young Readers 105 The Writer 107 The Book 109 The Characters 110 Other Classic Animal Stories 113 Test Yourself 115 Glossary 119 to all children children in years and children in heart i dedicate this story The Story of Doctor Dolittle 1 Puddleby nce upon a time, many years ago – when our grandfathers were little children – there was a doctor, and his name was Dolittle – John Dolittle, MD. -

The Story of DOCTOR DOLITTLE

1 The Story of DOCTOR DOLITTLE by Hugh Lofting Published by Ichthus Academy Doctor Dolittle ©Ichthus Academy 2 INTRODUCTION There are some of us now reaching middle age who discover themselves to be lamenting the past in one respect if in none other, that there are no books written now for children comparable with those of thirty years ago. I say written FOR children because the new psychological business of writing ABOUT them as though they were small pills or hatched in some especially scientific method is extremely popular today. Writing for children rather than about them is very difficult as everybody who has tried it knows. It can only be done, I am convinced, by somebody having a great deal of the child in his own outlook and sensibilities. Such was the author of "The Little Duke" and "The Dove in the Eagle's Nest," such the author of "A Flatiron for a Farthing," and "The Story of a Short Life." Such, above all, the author of "Alice in Wonderland." Grownups imagine that they can do the trick by adopting baby language and talking down to their very critical audience. There never was a greater mistake. The imagination of the author must be a child's imagination and yet maturely consistent, so that the White Queen in "Alice," for instance, is seen just as a child would see her, but she continues always herself through all her distressing adventures. The supreme touch of the white rabbit pulling on his white gloves as he hastens is again absolutely the child's vision, but the white rabbit as guide and introducer of Alice's adventures belongs to mature grown insight. -

Doctor Dolittle Jr. Character Breakdown

Doctor Dolittle Jr. Character Breakdown Doctor John Dolittle An eccentric country doctor who loves animals more than people. He is smart, passionate, driven and the consummate optimist, always looking for the best in every situation. Cast your very best singer and actor in this role. Madeline Mugg Dolittle's sassy friend who thoroughly enjoys the adventures she goes on with Dolittle. Madeline is Dolittle's compatriot, sharing his love and views of animals. This is a perfect role for a good singer who can act and has comic timing. Gender: Female Vocal range top: E5 Vocal range bottom: Bb3 Tommy Stubbins A happy-go-lucky kid who idolizes Doctor Dolittle and enjoys playing with the animals. Cast one of your high-spirited younger students who can act and sing. Gender: Male Vocal range top: D#5 Vocal range bottom: C4 Emma Fairfax A strong, tough woman who is willing to speak her mind. She learns to appreciate Dolittle's love of animals and grows to have feelings for him. Find a great singer and actor who can command the stage. Gender: Female Vocal range top: Db5 Vocal range bottom: Ab3 General Bellowes Emma's uncle and the magistrate of Puddleby-On-The-Marsh. An ill-tempered man with limited people skills, this non-singing role is perfect for a student with good stage presence and a powerful speaking voice. Gender: Male Albert Blossom A shrewd business man who owns a dilapidated touring circus. This curmudgeonly old guy is a nice character role for a solid singer and actor. Gender: Male Vocal range top: Eb5 Vocal range bottom: C4 Gertie Blossom One tough cookie. -

5 Other CFP 7-23-09.Indd 1 7/23/09 12:38:20 PM

Colby Free Press Thursday July 23, 2009 Page 5 On the Beat Books on music play well with festival COLBY POLICE 6:02 p.m. – Dead dog in road- Sunday, July 5 way. Turned over to Colby Animal I really enjoyed the bluegrass into being, their development “Choice Picks.” This will allow 12:05 a.m. – Subjects came to Clinic. festival this last weekend. In Melany through the ages, and even how the listener to learn many tradi- Law Enforcement Center to get 9:11 p.m. – Subjects using fi re- honor of it I want to share about Wilks they are actually made. This book tional bluegrass songs chosen by their dog. works. Spoke to them. a few books and other materials has wonderful photos illustrating the association. These items will 12:38 a.m. – Fireworks going 10:11 p.m. – Bush on fi re at we have on the theme of music. these topics as well as many other be available about the middle of off. Subjects spoken to. Brookside and Thompson. As- A wonderful children’s book is •Library subjects on “seeing sound” (pp. August; however you can always 12:42 a.m. – Assault reported. sisted Fire Department. “Banjo Granny,” by Sarah Martin Links 6-7); brass, drums and wind in- call and ask to put your name on 1:26 a.m. – 911 caller reported 10:34 p.m. – Assisted stalled ve- Busse and Jacqueline Briggs Mar- struments; learning about various a hold list so you can be one of unknown subjects trashing her hicle, Second and Mission Ridge. -

Programming Ideas

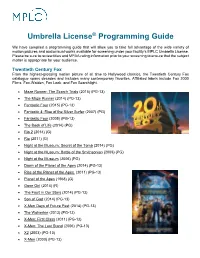

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

100 Rifles Worldwide 11 Harrowhouse Worldwide 12

100 Rifles Worldwide 11 Harrowhouse Worldwide 12 Rounds Worldwide 12 Rounds 2: Reloaded Worldwide 127 Hours Italy 20,000 Men a Year Worldwide 23 Paces to Baker Street Worldwide 27 Dresses Worldwide 28 Days Later Worldwide 3 Women Worldwide 45 Fathers Worldwide 500 Days of Summer Worldwide 9 to 5 Worldwide 99 and 44/100% Dead Worldwide A Bell For Adano Worldwide A Christmas Carol Worldwide A Cool Dry Place Worldwide A Cure for Wellness Worldwide A Farewell to Arms Worldwide A Girl in Every Port Worldwide A Good Day to Die Hard Worldwide A Guide for the Married Man Worldwide A Hatful of Rain Worldwide A High Wind in Jamaica Worldwide A Letter to Three Wives Worldwide A Man Called Peter Worldwide A Message to Garcia Worldwide A Perfect Couple Worldwide A Private's Affair Worldwide A Royal Scandal Worldwide A Tree Grows in Brooklyn Worldwide A Troll in Central Park Worldwide A Very Young Lady Worldwide A Walk in the Clouds Worldwide A Walk With Love and Death Worldwide A Wedding Worldwide A-Haunting We Will Go Worldwide Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter Worldwide Absolutely Fabulous Worldwide Ace Eli and Rodger of the Skies Worldwide Adam Worldwide Advice to the Lovelorn Worldwide After Tomorrow Worldwide Airheads Worldwide Alex and the Gypsy Worldwide Alexander's Ragtime Band Worldwide Alien Worldwide Alien Resurrection Worldwide Alien Vs. Predator Worldwide Alien: Covenant Worldwide Alien3 Worldwide Aliens Worldwide Aliens in the Attic Worldwide Aliens Vs. Predator - Requiem Worldwide All About Eve Worldwide All About Steve Worldwide All That -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

N -R 40 Value – 715-479-4421715-479-4421

(CNOW) 1-877-794-5751 Today Call Earthlink MusicandMore! StreamVideos, nology. Tech- Reliable HighSpeed FiberOptic As $14.95/month(for thefirst3months.) As Low Earthlink HighSpeed Internet. (CNOW) 1-855-711-0379 Of. CALL Care All Paperwork Taken Free Towing, Deductible, Tax Free 3DayVacation, BLIND. THE FOR HERITAGE TO BOAT YOUR CAR, TRUCK OR DONATE Call 1-855-997-5088(CNOW) Remote.Somerestrictionsapply. Voice lation, SmartHDDVRIncluded,Free $14.95 HighSpeedInternet.FreeInstal- TV $59.99For190Channels DISH 866-546-5275 CallNow!(CNOW) FreePriceQuote.1- A For Today CALL fied. Over1500medicationsavailable. Certi- tee! PrescriptionsRequired.CIPA HealthLink.PriceMatchGuaran- World PRESCRIPTION! YOUR NEXT ON SAVE (CNOW) www.refrigerantfinders.com or casesofcans.(312)291-9169; CA$HforR12cylinders BUYER willPAY CERTIFIED FREON R12WANTED: 330-5987 (CNOW) tomer careagentsawaityourcall.1-888- Sleep GuideandMore-FREE!Ourcus- Healthy cost inminutes.HomeDelivery, suppliesforlittleorno qualify forCPAP Healthcareto care coverage,callVerus Apnea Patients-IfyouhaveMedi- Sleep son 1-800-535-5727(CNOW) compensation. ContactCharlesH.John- SHOWER,youmaybeentitledto TO POWDERorSHOWER such asBABY products TALCUM afteruseof LIOMA CANCERorMESOTHE- with OVARIAN If youoralovedonewerediagnosed 866/368-9306 (CNOW) or available. sww.headsupST.com ment. Local,growerdrivendata Treat- Seed bean dealerforHeadsUP soy- Ask your WHITE MOLD IN2019! AGAINST PROTECT SOYBEAN 4421, ask for Ad Networkclassifieds. 4421, askfor (no copychanges).Call(715)479- Buy 4weeks,getthe5thweekfree