'Millennial Dreaming'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melbourne Press Club Laurie Oakes Address 15 September 2017

MELBOURNE PRESS CLUB LAURIE OAKES ADDRESS 15 SEPTEMBER 2017 Thank you all for coming. And thank you to the Melbourne Press Club for organizing this lunch. Although I’m based in Canberra, I’ve long felt a strong link with this club and been involved in its activities when I can-- including a period as one of the Perkin Award judges. Many of the members are people I’ve worked with over the years. I feel I belong. So this farewell means a lot to me. When I picked up the papers this morning, my first thought was: “God, I’m so old I knew Lionel Murphy.” In fact, I broke the story of his terminal cancer that shut down the inquiry. But making me feel even older was the fact that I’d even had a bit to do with Abe Saffron, known to the headline writers as “Mr Sin”, in my brief period on police rounds at the Sydney Mirror. Not long after I joined the Mirror, knowing nothing and having to be trained from scratch, a young journo called Anna Torv was given the job of introducing me to court reporting. The case involved charges against Mr Saffron based on the flimsy grounds, I seem to recall, that rooms in Lodge 44, the Sydney motel he owned that was also his headquarters, contained stolen fridges. At one stage during the trial a cauliflower-eared thug leaned across me to hand a note to Anna. It was from Abe saying he’d like to meet her. I intercepted it, but I don’t think Anna would have had much trouble rejecting the invitation. -

Inside the Canberra Press Gallery: Life in the Wedding Cake of Old

INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House INSIDE the CANBERRA PRESS GALLERY Life in the Wedding Cake of Old Parliament House Rob Chalmers Edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Chalmers, Rob, 1929-2011 Title: Inside the Canberra press gallery : life in the wedding cake of Old Parliament House / Rob Chalmers ; edited by Sam Vincent and John Wanna. ISBN: 9781921862366 (pbk.) 9781921862373 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Australia. Parliament--Reporters and Government and the press--Australia. Journalism--Political aspects-- Press and politics--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Vincent, Sam. Wanna, John. Dewey Number: 070.4493240994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Back cover image courtesy of Heide Smith Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Foreword . ix Preface . xi 1 . Youth . 1 2 . A Journo in Sydney . 9 3 . Inside the Canberra Press Gallery . 17 4 . Menzies: The giant of Australian politics . 35 5 . Ming’s Men . 53 6 . Parliament Disgraced by its Members . 71 7 . Booze, Sex and God . -

Some Notes on DTE and Confest

ConFest and the Next 250 Years Past and Future Possibilities Dr Les Spencer, 1992. Revised 2014. Use within grassroots mutual-help processes for non-profit purposes 1 Contents Contents .................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Pre-Confest Speech By Dr Jim Cairns ...................................................................... 4 Manifesto From The First Confest – Cotter River 1976 ............................................. 5 The Evolving Of The First Confest ............................................................................ 7 Founding History Of Social Transforming Action ....................................................... 6 T2 Mobilising Transnationals – Visits To Confest & Follow-On ................................. 6 Dte Visits: .............................................................................................................. 6 International Natural Nurturer Networking ................................................................ 6 The Evolving Of The First Confest ............................................................................ 7 Wellbeing Action Using Festivals, Gatherings And Other Happenings ..................... 9 The Watsons Bay Festival ......................................................................................... 9 Working With Free Energy ...................................................................................... 10 The Second Festival – The Paddington Festival .................................................... -

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83 Edited by Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins © The Australian Institute of International Affairs 2018 ISBN: 978-0-909992-04-0 This publication may be distributed on the condition that it is attributed to the Australian Institute of International Affairs. Any views or opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily shared by the Australian Institute of International Affairs or any of its members or affiliates. Cover Image: © Tony Feder/Fairfax Syndication Australian Institute of International Affairs 32 Thesiger Court, Deakin ACT 2600, Australia Phone: 02 6282 2133 Facsimile: 02 6285 2334 Website:www.internationalaffairs.org.au Email:[email protected] Table of Contents Foreword Allan Gyngell AO FAIIA ......................................................... 1 Editors’ Note Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins CSC ........................ 3 Opening Remarks Zara Kimpton OAM ................................................................ 5 Australian Foreign Policy 1972-83: An Overview The Whitlam Government 1972-75: Gough Whitlam and Don Willesee ................................................................................ 11 Professor Peter Edwards AM FAIIA The Fraser Government 1975-1983: Andrew Peacock and Tony Street ............................................................................ 25 Dr David Lee Discussion ............................................................................. 49 Moderated by Emeritus Professor Peter Boyce AO Australia’s Relations -

Redefining the Australian Nation

Jesuit Jubilee Conference Evangelisation and Culture in a Jesuit Light Friday 28 July-Sunday 30 July 2006 St Patrick's Campus, Australian Catholic University, liS Victoria Pde, Fitzroy Major Speakers include Fr Daniel Madigan SJ Director of the Pontifical Institute for the Study of Religions and Culture, Rome Fr Frank Brennan SJ AO Institute of Legal Studies, Australian Catholic University Program begins Friday 7pm and ends with Mass, celebrated by Bishop Hilton Deakin, at 4pm on Sunday. Provisional charges, including light meal Friday, lunches and refreshments: Full conference $1 00; Friday evening, $25; Saturday or Sunday only, $50 (unwaged $60, $15 and $30, respectively). Conference dinner (optional) Saturday night. For more information contact Jesuit Theological College. Telephone OJ 9341 5800 Email [email protected] Sponsored by ~ACU ~c ~1ona· Jesuit Theological College Australia n Ca tholic University Rro\b.!<lt' \yantoy C.tn~"• Ball•••t M~lboume \lh II~ \II.\\ .... II 'UI I ' ' Go shopping with $Io~ooo The winner of this year's jesuit Communications Plea se note that our custom ha s been to se nd a book of raffle tickets to each subscriber to thi s magazine. If yo u do not wish to re ce ive the Australia Raffle gets to go shopping in a big way! tickets, plea se return the form below, by mail or fa x, or co ntact us directly at: First prize is a $10,000 shopping voucher for Harvey Norman PO Box 553, Richmond, Vic 3121 Telephone 03 9427 7311 , fax 03 9428 4450 stores . And please remember that your entry is one of the email [email protected] ways you can help ensure the continuing financial viability of Jesuit Communications Au stralia . -

A Retrospective View of the 1975 Apsa Conference. I. the Conference and the Authors

KING GOUGH : MADNESS OR MAGNIFICENCE ? A RETROSPECTIVE VIEW OF THE 1975 APSA CONFERENCE. Professor Roger Scott Kate Wiillson Professor of Publliic Management Snr. Research Offiicer / Tutor, Applliied Ethiics Facullty of Busiiness Facullty of Busiiness / Arts Queenslland Uniiversiity of Technollogy Queenslland Uniiversiity of Technollogy I. THE CONFERENCE AND THE AUTHORS In 2000, I chose to mark the 25th anniversary by a personal project to complement the formal conference on the topic of the Whitlam years held later in the year on the specific anniversary. As President of APSA in that momentous year, I chaired the committee which organised the conference that year, held amid damp conditions at the Canberra CAE. The conference occurred in the hothouse environment of July 1975, a period of unprecedented levels of political uncertainty. Indeed, the very title of the conference, “The First Thousand Days of Labor” devised by John Power inadvertently begged a momentous question: Would Whitlam last beyond his first thousand days? Answer – just, 1074. The attendance at the conference, over 400 including the down-town public servants, was also abnormally large. Finally, the format of the conference, squeezing all contributors into a straight-jacket of a single theme, was also an innovation – and never repeated because some vocal groups felt disenfranchised by its intellectual parochialism. These special characteristics of the conference justify this exercise in retrospectivity. It fits into a theme of reviewing Australian federalism since 1975 was such a cataclysmic year. It was a mirror of where the Whitlam government was taking the public policy agenda – towards institutional reforms in the public service, reaching into local and regional communities, creating new slants on federalism and engaging in an activist and independent foreign policy (not least with respect to East Timor). -

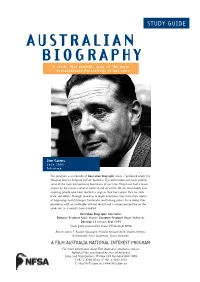

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time Jim Cairns 1914–2003 Politician This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 7 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Jim Cairns Director/Producer Robin Hughes Executive Producer Megan McMurchy Duration 26 minutes Year 1999 Study guide prepared by Diane O’Flaherty © Film Australia Also in Series 7: Rosalie Gascoigne, Priscilla Kincaid-Smith, Charles Perkins, Bill Roycroft, Peter Sculthorpe, Victor Smorgon A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: Film Australia Sales, PO Box 46 Lindfield NSW 2070 Tel 02 9413 8634 Fax 02 9416 9401 Email [email protected] www.filmaust.com.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: JIM CAIRNS 2 SYNOPSIS WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS? Throughout the 1960s and 70s Dr Jim Cairns held a unique position In the Labor Party in Australian public life as the intellectual leader of the political left. GOUGH WHITLAM: Prime Minister of Australia from December 1972 As a senior and influential member of the Whitlam Government, he to November 1975, he was the first Labor prime minister since was involved in many of its achievements and also heavily implicated 1949. -

15. Darkness Descends on Whitlam

15. Darkness Descends on Whitlam An important factor in the downfall of the Whitlam Government was the affair involving the Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Jim Cairns, and Junie Morosi. The media could not get enough of the yarn—splashed as a ‘bombshell sex story’. Cairns’ colleagues in the Caucus and journalists in the gallery were, to say the least, surprised. Until then, it had been assumed that Cairns and his devoted wife of many years were inseparable. Morosi turned up, out of the blue, becoming a regular visitor to the office of the Leader of the Government in the Senate, Minister for Customs and Attorney-General, Lionel Murphy. She was a stunning beauty, slender, with beautiful black hair—in short, a knockout. Morosi was not on Murphy’s staff but the general view around Parliament was that Murphy was ‘knocking her off’. Murphy came to the Parliament as a NSW Senator in 1962. His promotion was rapid: Leader of the Opposition in the Senate in 1967 and Leader of the Government in the Senate when Whitlam came to power in 1972. With his promotion came a more commodious office, allowing him, when the Senate rose for the night, to host some of the best parties in Parliament House. Frequently, the parties would, in the early hours of the morning, move to Murphy’s fine house in Arthur Circle, Forrest—an exclusive address. Lionel’s gorgeous wife, Ingrid, a former model, was the hostess. No matter how late the party, Murphy would be in Parliament House next morning bright and early. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1975

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly THURSDAY, 13 MARCH 1975 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy Matters of Public Interest (13 MARCH 1975] Papers 249 THURSDAY, 13 MARCH 1975 Mr. SPEAKER (Hon. J. E. H. Houghton, Redcliffe) read prayers and took the chair at 11 a.m. PAPERS The following paper was laid on the table, and ordered to be printed:- Report of the Department of Primary Industries for the year 1973-74. The following papers were laid on the table:- Orders in Council under- The Agricultural Bank (Loans) Act of 1959. The City of Brisbane Market Acts, 1960 to 1967. Co-ordination of Rural Advances and Agricultural Bank Act 1938-1969. Dairy Products Stabilisation Act 1933- 1972. Explosives Act 1952-1974. Fauna Conservation Act 1974. Fish Supply Management Act 1972. Meat Industry Act 1965-1973. The Milk Supply Acts, 1952 to 1961. Plague Grasshoppers Extermination Act 1937-1971. Primary Producers' Organisation and Marketing Act 1926-1973. Regulation of Sugar Cane Prices Act 1962-1972. Sugar Experiment Stations Act 1900- 1973. Swine Compensation Fund Act 1962- 1969. Wheat Pool Act 1920-1972. 250 Questions Upon Notice [13 MARCH 1975] Questions Upon Notice Regulations under- (2) "The names of the Directors ef Agricultural Standards Act 1952-1972. Lae Enterprises may be obtained from Dairy Products Stabilisation Act 1933- the Commissioner for Corporate Affairs, 1972. Anzac Square Government Buildings, Fruit and Vegetable Act 1947-1972. Adelaide Street." Hen Quotas Act 1973. (3) "The Clean Air Act is directed Hospitals Act 1936-1971. towards industry, and land development Meat Industry Act 1965-1973. does not come within the scope of the Primary Producers' Organisation and regulations." Marketing Act 1926-1973. -

A Brief History of Australia

A Br i e f Hi s t o r y o f Au s t r A l i A A Br i e f Hi s t o r y o f Au s t r A l i A BA r ba r A A. We s t w i t h Fr a n c e s t. Mu r p h y A Brief History of Australia Copyright © 2010 by Barbara A. West All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data West, Barbara A., 1967– A brief history of Australia / Barbara A. West with Frances T. Murphy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8160-7885-1 (acid-free paper) 1. Australia—History. I. Murphy, Frances T. II. Title. DU108.W47 2010 994—dc22 2009031925 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Excerpts included herewith have been reprinted by permission of the copyright holders; the author has made every effort to contact copyright holders. -

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time Jim Cairns 1914–2003 Politician This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 7 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Jim Cairns Director/Producer Robin Hughes Executive Producer Megan McMurchy Duration 26 minutes Year 1999 Study guide prepared by Diane O’Flaherty © NFSA Also in Series 7: Rosalie Gascoigne, Priscilla Kincaid-Smith, Charles Perkins, Bill Roycroft, Peter Sculthorpe, Victor Smorgon A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Sales and Distribution | PO Box 397 Pyrmont NSW 2009 T +61 2 8202 0144 | F +61 2 8202 0101 E: [email protected] | www.nfsa.gov.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: JIM CAIRNS 2 SYNOPSIS WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS? Throughout the 1960s and 70s Dr Jim Cairns held a unique position In the Labor Party in Australian public life as the intellectual leader of the political left. -

Antique Bookshop

ANTIQUE BOOKSHOP CATALOGUE 339 The Antique Bookshop & Curios ABN 64 646 431062 Phone Orders To: (02) 9966 9925 Fax Orders to: (02) 9966 9926 Mail Orders to: PO Box 7127, McMahons Point, NSW 2060 Email Orders to: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.antiquebookshop.com.au Books Held At: Level 1, 328 Pacific Highway, Crows Nest 2065 Hours: 10am to 5pm, Tuesday to Saturday All items offered at Australian Dollar prices subject to prior FOREWORD These days it seems that our dealings with other entities, government sale. Prices include GST. Postage & insurance is extra. or private, are increasingly transacted on-line. Payment is due on receipt of books. For ordering products, renewing insurance policies or car registration, No reply means item sold prior to receipt of your order. sending data to government bodies, submitting an application to at- tend an event or undertake a course, booking a restaurant or for many Unless to firm order, books will only be held for three days. other things, the preferred method will be on-line. You may eventually get to talk to someone if you have a problem but they’re always reluctant to do so and you may have a long wait to be CONTENTS connected, and once connected you may then be talking to someone in a call centre whose grasp of English is less than perfect or whose BOOKS OF THE MONTH 1 - 30 accent makes them difficult to understand. AUSTRALIAN POLITICS 31 - 60 We are constantly inundated with emails trying to lure us into AUSTRALIA & THE PACIFIC 61 - 211 clicking on links that will introduce some kind of malware in to our MISCELLANEOUS 212 - 393 computers.