Global Environment Facility (GEF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Agricultural Information Needs in Acp African States -West Africa

ASSESSMENT OF AGRICULTURAL INFORMATION NEEDS IN ACP AFRICAN STATES -WEST AFRICA Country Study: The Gambia Final Report Prepared by: Mamadi Baba Ceesay on behalf of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) Project: 4-7-41-254-7/e 30 July, 2008 ASSESSMENT OF AGRICULTURAL INFORMATION NEEDS IN ACP AFRICAN STATES -WEST AFRICA Country Study: The Gambia Final Report Prepared by: Mamadi Baba Ceesay on behalf of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) Project: 4-7-41-254-7/e 30 July, 2008 Disclaimer This report has been commissioned by the CTA to enhance its monitoring of information needs in ACP countries. CTA does not guarantee the accuracy of data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of CTA. CTA reserves the right to select projects and recommendations that fall within its mandate. (ACP-EU) Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) Agro Business Park 2 6708 PW Wageningen The Netherlands Website: www.cta.int E-mail: [email protected] i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A vast number of people and institutions provided valuable support during the study and their efforts are gratefully acknowledged. I wish to however single out just a few. Alpha Sey and Seedy Demba provided Research Assistance, Dr. Omar Touray provided valuable insight on sources of information and Ellen Sambou Sarr provided secretarial support. I wish to express warmest gratitude to the Regional Study Coordinator Yawo Assigbley for the very useful editorial support. -

République Islamique De Gambie Évaluation Du Programme De Pays

Cote du document: EB 2019/126/R.10 Point de l’ordre du jour: 5 b) ii) Date: 11 avril 2019 F Distribution: Publique Original: Anglais République islamique de Gambie Évaluation du programme de pays Note à l'intention des représentants du Conseil d'administration Responsables: Questions techniques: Transmission des documents: Oscar A. Garcia Deirdre McGrenra Directeur du Cheffe de l'Unité Bureau indépendant de l’évaluation du FIDA des organes directeurs téléphone: +39 06 5459 2274 téléphone: +39 06 5459 2374 courriel: [email protected] courriel: [email protected] Fumiko Nakai Fonctionnaire principale chargée de l’évaluation téléphone: +39 06 5459 2283 courriel: [email protected] Conseil d'administration — Cent vingt-sixième session Rome, 2-3 mai 2019 Pour: Examen EB 2019/126/R.10 Table des matières Remerciements ii Résumé iii Appendices I. Agreement at Completion Point 1 II. Main report—Islamic Republic of The Gambia Country Programme Evaluation 11 i EB 2019/126/R.10 Remerciements Ce rapport d’évaluation de programme de pays (EPP) a été préparé par Louise McDonald, ancienne Fonctionnaire chargée de l’évaluation au Bureau indépendant de l’évaluation du FIDA (IOE) et Cécile Berthaud, ancienne Fonctionnaire principale d’IOE chargée de l’évaluation. Elles ont bénéficié de l’appui compétent des consultants suivants: Herma Majoor, responsable de l’équipe de consultants; Liz Kiff, spécialiste des questions agricoles et environnementales; Thierry F. Mahieux, spécialiste de la finance rurale et du développement des entreprises; Siga Fatima Jagne, spécialiste gouvernementale des questions d’égalité des sexes et du pays; Yahya Sanyang, ingénieur; Natalia Ortiz, spécialiste en méthodologie de l’évaluation; et Marina Izzo, ancienne consultante d’IOE qui a réalisé l’examen documentaire. -

Review of the Livestock/Meat and Milk Value Chains and Policy Influencing Them in the Gambia

REVIEW OF THE LIVESTOCK/MEAT AND MILK VALUE CHAINS AND POLICY INFLUENCING THEM IN THE GAMBIA ii REVIEW OF THE LIVESTOCK/MEAT AND MILK VALUE CHAINS AND POLICY INFLUENCING THEM IN THE GAMBIA Omar Touray Edited by Olanrewaju B. Smith Abdou Salla Berhanu Bedane Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Economic Community of West African States 2016 i The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), or of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO, or ECOWAS in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO, or the ECOWAS. © FAO and ECOWAS, 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

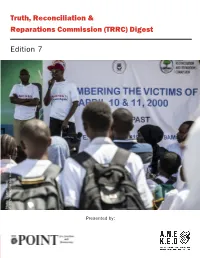

Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) Digest Edition 7

Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) Digest Edition 7 Jason Florio © Photo: Newspaper The Point ANEKED & © 2019 Presented by: 1| The Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) is mandated to investigate and establish an impartial historical record of the nature, causes and extent of violations and abuses of human rights committed during the period of July 1994 to January 2017 and to consider the granting of reparations to victims and for connected matters. It started public hearings on 7th January 2019 and will proceed in chronological order, examining the most serious human rights violations that occurred from 1994 to 2017 during the rule of former President Yahya Jammeh. While the testimonies are widely reported in the press and commented on social media, triggering vivid discussions and questions regarding the current transitional process in the country, a summary of each thematic focus/event and its findings is missing. The TRRC Digests seek to widen the circle of stakeholders in the transitional justice process in The Gambia by providing Gambians and interested international actors, with a constructive recount of each session, presenting the witnesses and listing the names of the persons mentioned in relation to human rights violations and – as the case may be – their current position within State, regional or international institutions. Furthermore, the Digests endeavour to highlight trends and patterns of human rights violations and abuses that occurred and as recounted during the TRRC hearings. In doing so, the TRRC Digests provide a necessary record of information and evidence uncovered – and may serve as “checks and balances” at the end of the TRRC’s work. -

Commission Ii Commission Ii Comision Ii

conference C FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS conférence C 95/II/PV ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'ALIMENTATION ET L'AGRICULTURE conferencia ORGANIZACION DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA AGRICULTURA Y LA ALIMENTACION Twenty-eighth Session Vingt-huitième session 28° período de sesiones COMMISSION II COMMISSION II COMISION II Rome, 20-31 October 1995 VERBATIM RECORDS OF MEETINGS OF COMMISSION II OF THE CONFERENCE PROCÈS-VERBAUX DES SÉANCES DE LA COMMISSION II DE LA CONFÉRENCE ACTAS TAQUIGRAFICAS DE LAS SESIONES DE LA COMISION II DE LA CONFERENCIA - iii - Iii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE DES MATIERES INDICE FIRST MEETING PREMIERE SEANCE PRIMERA SESION (21 October 1995) Page/Página II ACTIVITIES AND PROGRAMMES OF THE ORGANIZATION II ACTIVITES ET PROGRAMMES DE L'ORGANISATION 2 II ACTIVIDADES Y PROGRAMAS DE LA ORGANIZACION 14. Programme Implementation and Programme Evaluation Reports 1994-95 (C 95/4; C 95/4-Corr.1 (Arabic only); C 95/8; C 95/LIM/3; C 95/LIM/9) 14. Rapports d'exécution du Programme et d'évaluation du Programme 1994-95 (C 95/4; C 95/4-Corr.1 (arabe seulement); C 95/8; C 95/LIM/3; C 95/LIM/9) 2 14. Informes sobre la ejecución y la evaluación del Programa de 1994-95 (C 95/4; C 95/ 4-Corr.1 (sólo en árabe); C 95/8; C 95/LIM/3; C 95/LIM/9) SECOND MEETING DEUXEME SESSION SEGUNDA SESION (21 October 1995) II. ACTIVITES AND PROGRAMMES OF THE ORGANIZATION(continued) II. ACTIVITES ET PROGRAMMES DE L'ORGANISATION (suite) 18 II. -

Government of Gambia Capacity Building in Support of Preparation of Economic Partnership Agreement (8 ACP TPS 110) #103 - Gambia

Government of Gambia Capacity Building in Support of Preparation of Economic Partnership Agreement (8 ACP TPS 110) #103 - Gambia Impact Assessment Final Report© June 2005 ADDRESS TELEPHONE FACSIMILE EMAIL WEBSITE Enterplan Limited +44 (0) 118 956 6066 +44 (0) 118 957 6066 [email protected] www.enterplan.co.uk 1 Northfield Road Reading RG1 8AH, UK Contents Contents Executive Summary i Background i Methodology of the EPA Impact Study ii Economic Environment and Outlook iii Trade Policy Institutional Framework iii The Gambia’s International Trade Flows iv The Evolving EU Policy and Context iv Assessment of EPA Impact on FDI v Impact of the EPA on Trade Flows v Fiscal Impact of the EPA v Adjustment Costs and Flanking Measures vi Adjustments Required in Public Sector Management vi Competitive Adjustments vii National Consensus Building vii Trade Related Training Needs viii Capacity Building Requirements viii Recommendations for the EPA Negotiations viii EPA Negotiation Principles ix The Gambian Objectives for Negotiating an ECOWAS-EU EPA ix Proposed Areas and Approach to Negotiation x Recommendations Concerning Third Parties xi Policy Options xii 1 Purpose and Approach of the 1 Study Background 1 The Gambia’s EPA Project 2 The Gambia / Support of Preparation of EPA / Impact Assessment Final Report / June 2005 Contents 2 Economic Environment and 5 Outlook Introduction 5 Structure and Main Features of the Economy 5 Recent Economic Performance 6 Fiscal Management 6 Inflation and Exchange Rates 7 Major Development Challenges 7 Domestic -

A Case of the Eastern Africa Standby Force

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES (IDIS) THE ROLE OF AFRICA STANDBY FORCE IN SECURING AFRICA: A CASE OF THE EASTERN AFRICA STANDBY FORCE BY MAKATO LOISE MWIKALI R50/88442/2016 SUPERVISOR PROF MARIA NZOMO A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI DECEMBER 2018 i DECLARATION I, Loise Makato, hereby declare that this research project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University. Signed……………………………………… Date…………………………. MAKATO LOISE MWIKALI R50/88442/2016 This project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor; Signed……………………………………. Date……………………………. PRO. MARIA NZOMO University Supervisor Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION I dedicate this study to my sons Ryan Muoki, Eythan Makato &Dylan Kimonyi (RED) and in a very special way to my husband Kenneth Mule. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank the Almighty God for giving me the zeal, privilege, wisdom and guidance to conduct this study. I pay tribute to my family, my sons who endured my absence most of the evenings and weekends over the past year, at times accompanying me to school. Mygood- hearted husbandKenneth Mule who enabled my study as a moral and financial backer deserves a special mention in this regard. Alex Makato and Victorine Kyalo, your support was incomparable, thank you. In Addition, I want to thank my supervisor Professor Maria Nzomo for her unsurpassed guidance and dedication that allowed for a conducive academic process that allowed completion of this study. -

Vol.1I Afsol Journal.Pdf

Title Page Title Page AfSol Journal Journal of African-Centered Solutions in Peace and Security Vol. 1 (1) August 2016 Copyright © 2016 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University Printed in Ethiopia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording or inclusion in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Institute for Peace and Security Studies. The views expressed in this journal are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. ISSN 2518-8135 Journal of African-Centred solutions in peace and security J. Afr.-centred solut. peace secur. AfSol journal AfSol Journal Volume 1, Issue 1 i About the Journal The Journal of African-Centred solutions in peace and security (AfSol Journal) is one of the research products of the Institute for Peace and Security Studies (IPSS) which serves as a platform for critical debate and solutions on African peace and security challenges. It aims at meeting peace and security as an intellectual challenge and avails theoretical and practical knowledge to academia and policy makers. AfSol Journal would like to draw this knowledge from newly-emerging practices and from past experiences to be found hidden in oral verses and practices of Africans, written in academic publications, daily periodicals, and policy documents. It is embedded in what Africa has achieved in the past and in what it could have done better; it is entrenched in its history, its traditions, values and its people. -

Final Evaluation Report for SCED Gambia.Pdf

International Trade Centre Final Evaluation Report v3a April 2016 Final Evaluation of Sector Competitiveness & Export Diversification in The Gambia Partner of the Centre for Global Competitiveness and Performance of the World Economic Forum: Sierra Leone & Liberia Financial Management Capacity Building Development & Strategy Development & Management Consultants Christ Church Complex Rear Elton Station Westfield, KSMD. (E-Mail) [email protected] (Tel) + 220 7073200 (Tel) + 220 4396101 (Web) www.fjp-consulting.com Mr. M. Jimenez Pont Head, Monitoring & Evaluation Unit Office of the Executive Director International Trade Centre By email: [email protected] 27 April 2016 Dear Miguel, Revised Final Evaluation Report: Final Evaluation of Sector Competitiveness & Export Diversification in The Gambia Greetings. We are pleased to submit our revised final evaluation report for your consideration. This incorporates the clarifications received on the responsibility of the EIF Board for action on recommendations arising from the evaluation. Thank you for your investment in our services. Yours sincerely, Dr. Omodele R. N. Jones DBA (National Competitive Strategy, Heriot-Watt) MSc (Heriot-Watt) BA (Essex) FCA (UK) Lead Evaluator [email protected] Enclosures Financial Management Capacity Building Development & Strategy Partner of the Centre for Global Competitiveness and Performance of the World Economic Forum: Sierra Leone & Liberia Christ Church Complex, Off Sayerr Jobe Avenue, Serrekunda, THE GAMBIA. Tel: +220 707 3200 / 4396101. [email protected]. -

Secretariat Distr.: Limited

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.625 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 16 December 2016 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTY-FIRST SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 46 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 47 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 48 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 49 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 50 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 52 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 53 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Proceedings of the USAID Natural Resources Management and Environmental Policy Conference

SD Publication Series Office of Sustainable Development Bureau for Africa Proceedings of the USAID Natural Resources Management and Environmental Policy Conference Banjul, The Gambia January 18–22, 1994 Technical Paper No. 2 November 1994 SD Technical Papers Office of Sustainable Development Bureau for Africa U.S. Agency for International Development The series includes the following publications: 1 / Framework for Selection of Priority Research and Analysis Topics in Private Health Sector Development in Africa *2 / Proceedings of the USAID Natural Resources Management and Environmental Policy Conference: Banjul, The Gambia / January 18-22, 1994 *3 / Agricultural Research in Africa: A Review of USAID Strategies and Experience *4 / Regionalization of Research in West and Central Africa: A Synthesis of Workshop Findings and Recommendations (Banjul, The Gambia. March 14-16, 1994) *5 / Developments in Potato Research in Central Africa *6 / Maize Research Impact in Africa: The Obscured Revolution / Summary Report *7 / Maize Research Impact in Africa: The Obscured Revolution / Complete Report *8 / Urban Maize Meal Consumption Patterns: Strategies for Improving Food Access for Vulnerable Households in Kenya *9 / Targeting Assistance to the Poor and Food Insecure: A Literature Review 10 / An Analysis of USAID Programs to Improve Equity in Malawi and Ghana's Education Systems *11 / Understanding Linkages among Food Availability, Access, Consumption, and Nutrition in Africa: Empirical Findings and Issues from the Literature *12 / Market-Oriented -

The Gambia Second Generation National Agricultural Investment Plan-Food and Nutrition Security (GNAIP II-FNS)

The Government of the Gambia The Gambia Second Generation National Agricultural Investment Plan-Food and Nutrition Security (GNAIP II-FNS) 2019-2026 i Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. IV PART 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 KEY MACRO-ECONOMIC AND FOOD AND / NUTRITION SECURITY INDICATORS .................................................................... 1 1.2 THE ORIGIN AND FORMULATION OF SECOND GENERATION GNAIP-FNS .......................................................................... 2 1.3 THE GNAIP II FORMULATION OVERSEEING PROCESS .................................................................................................... 4 1.3.1 GNAIP II Formulation Overseeing Process ..................................................................................................... 4 1.3.2 Country’s Basic Strategy Development Blue Prints ....................................................................................... 6 PART II ASSESSMENT OF THE FIRST GENERATION NAIP .............................................................................................. 9 2.1 THE GROWTH PERFORMANCE OF SECTORS (EXTERNAL EFFECTIVENESS OF THE NAIP) ......................................................... 9 2.1.1 ANR Growth Performance ................................................................................................................................