PETER JOSHUA SCULTHORPE Ao Obe 1929–2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LS17.17022-Program-Web

ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO The CSO is assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body New Combination “Bean” Lorry No.341 commissioned 31st December 1925. 115 YEARS OF POWERING PROGRESS TOGETHER Since 1901, Shell has invested in large projects which have contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy. We value our partnerships with communities, governments and industry. And celebrate our longstanding partnership with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. shell.com.au Photograph courtesy of The University of Melbourne Archives 2008.0045.0601 SHA3106__CSO_245x172_V3.indd 1 20/09/2016 2:53 PM ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO Wednesday 17 May & Thursday 18 May, 2017 Llewellyn Hall, ANU 7.30pm Conductor Stanley Dodds Cello Umberto Clerici ----- HAYDN: Overture to L’isola disabitata (The Desert Island), Hob 28/9 8’ SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 25’ 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Langsam 3. Sehr lebhaft INTERMISSION SCULTHORPE: String Sonata No. 3 (Jabiru Dreaming) 8’ 1 Deciso 2 Liberamente – Estatico BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, op. 90 33’ 1. Allegro con brio 2. Andante 3. Poco allegretto 4. Allegro Please note: this program is correct at time of printing, however it is subject to change without notice. Umberto Clerici’s performance is supported by the Embassy of Italy in Canberra, Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Sydney and Schiavello enterprise Cover photo by Sarah Walker Sarah Cover photo by 17022 SEASON 2017 ActewAGL Llewellyn Series: Cello, Horn, Violin “Music -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

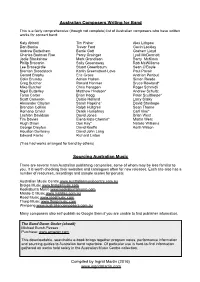

Australian Composers & Sourcing Music

Australian Composers Writing for Band This is a fairly comprehensive (though not complete) list of Australian composers who have written works for concert band: Katy Abbott Tim Fisher Alex Lithgow Don Banks Trevor Ford Gavin Lockley Andrew Batterham Barrie Gott Graham Lloyd Charles Bodman Rae Percy Grainger Lyall McDermott Jodie Blackshaw Mark Grandison Barry McKimm Philip Bracanin Sally Greenaway Rob McWilliams Lee Bracegirdle Stuart Greenbaum Sean O’Boyle Brenton Broadstock Karlin Greenstreet-Love Paul Pavoir Gerard Brophy Eric Gross Andrian Pertout Colin Brumby Adrian Hallam Simon Reade Greg Butcher Ronald Hanmer Bruce Rowland* Mike Butcher Chris Henzgen Roger Schmidli Nigel Butterley Matthew Hindson* Andrew Schultz Taran Carter Brian Hogg Peter Sculthorpe* Scott Cameron Dulcie Holland Larry Sitsky Alexander Clayton Sarah Hopkins* David Stanhope Brendan Collins Ralph Hultgren Sean Thorne Romano Crivici Derek Humphrey Carl Vine* Lachlan Davidson David Jones Brian West Tim Davies Elena Kats-Chernin* Martin West Hugh Dixon Don Kay* Natalie Williams George Dreyfus David Keeffe Keith Wilson Houston Dunleavy David John Lang Edward Fairlie Richard Linton (*has had works arranged for band by others) Sourcing Australian Music There are several main Australian publishing companies, some of whom may be less familiar to you. It is worth checking their websites and catalogues often for new releases. Each site also has a number of resources, recordings and sample scores for perusal. Australian Music Centre www.australianmusiccentre.com.au Brolga Music www.brolgamusic.com Kookaburra Music www.kookaburramusic.com Middle C Music www.middlec.com.au Reed Music www.reedmusic.com Thorp Music www.thorpmusic.com Wirripang www.australiancomposers.com.au Many composers also self-publish so Google them if you are unable to find publisher information. -

INSIDE the MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE at 75 by John Clare*

INSIDE THE MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE AT 75 by John Clare* __________________________________________________ INSIDE THE MUSICIAN is a series of articles on the Music Trust of Australia website by music people of all kinds, revealing something about their musical worlds and how they experience them. This article appeared on June 5, 2016. To read this on that website, go to this link http://musictrust.com.au/loudmouth/inside-the-musician-john-clare-75/ o come in from a wide or oblique angle, I need to apologise briefly that my writing is not what it was. There is no excuse, but a reason of sorts. Over the T past few years I have lost a son and a sister, the wonderful old Chinese lady upstairs who died and was replaced by a crazy and nasty woman who fire bombed my flat while I was visiting my daughter in Brisbane. And more, but we’ll leave that. Perhaps this stress and distress is behind my two strokes and a triple A operation (aortic aneurism in the aorta) which comprehensively relieved me of my memory for a while. Concentration is difficult and death seems often to be hovering. Yet strangely I am very fit and can race up very steep hills on my bike or grind up on the seat. It is when I am lying down and for some time afterward that it surrounds me. We’ll leave it at that. More important than that is how music sounds and what it means in what may well be the end days. Mine anyway. Like vapour trails soaring straight up at space from the horizon, or so it seems, but finding the curvature of the earth almost directly above. -

Only the Dead

SCREEN AUSTRALIA PRESENTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION ONLY THE DEAD PRODUCTION NOTES Running time: 77:11 ONLY THE DEAD Directed by BILL GUTTENTAG and MICHAEL WARE Written by MICHAEL WARE Produced by PATRICK MCDONALD Produced by MICHAEL WARE Executive Producer JUSTINE A. ROSENTHAL Editor JANE MORAN Music by MICHAEL YEZERSKI Associate Producer ANDREW MACDONALD • SCREEN AUSTRALIA /PRESENTS A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL ONLY THE DEAD One Line Synopsis What happens when one of the most feared, most hated terrorists on the planet chooses you—personally—to reveal his arrival on the global stage? All in the midst of the American war in Iraq? Short Synopsis Theatrical feature documentary Only the Dead is the story of what happens when one ordinary man, an Australian journalist transplanted into the Middle East by the reverberations of 9/11, butts into history. It is a journey that courses through the deepest recesses of the Iraq war, revealing a darkness lurking in his own heart. A darkness that he never knew was there. The invasion of Iraq has ended, and the Americans are celebrating victory. The year is 2003. The international press corps revel in the Baghdad “Summer of Love”, there is barely a spare hotel room in the entire city. Reporters of all nationalities scramble for stories; of the abuses of Saddam’s fallen regime; of WMD’s, of reconstruction, of liberation. There are pool parties, and restaurant outings, and dinner-party circuits. Occasionally, Coalition forces are attacked, but always elsewhere, somewhere in the background. -

SCORING ESSINGTON: Composition, Comprovisation

Screen Sound n2, 2011 SCORING ESSINGTON Composition, Comprovisation, Collaboration Michael Hannan Abstract New music technologies have increasingly enabled elements of improvised score to be incorporated into screen music tracks, even where a score is devised for performance by orchestral ensembles. This article focuses on the music construction for a film produced for (colour) television in the first decade of the Australian cinema revival period. In 1974 the author collaborated with composers Peter Sculthorpe and David Matthews on the production of the music score for the Australian feature-length drama, Essington (Julian Pringle, 1974). This reflective practice article outlines the creative ideas behind the composition of the Essington score and focuses on comprovisation (composition involving improvisation) as distinct from then-common practice in film scoring of fully notating the underscore. In scoring Essington’s music, comprovised cues, produced mostly using unconventional piano ‘interior’ sounds (where the sounds are produced by direct contact with the strings rather than using the keyboard), were used to sonically contrast with fully notated cues written in a conventional way for the piano. This study analyses a collaborative approach that offers a useful model for contemporary (Australian) film composition practices. Keywords Australian film music, Peter Sculthorpe, improvisation, comprovisation, piano interior Introduction Essington, a television feature film made by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) for the introduction of colour television1, is an historical drama written by well- established historical novelist Thomas Keneally, directed by Julian Pringle and produced by Brian Burke. Essington’s storyline centres on the difficulties faced by British colonial settlers in coping with the harshness and strangeness of the Australian continent in the 1840s. -

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Answers to Senate Estimates Questions on Notice Supplementary Budget Estimates Hearings October 2012 Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy Portfolio Australian Broadcasting Corporation Question No: 139 Program No. ABC Hansard Ref: Page 73 Topic: Mr Loewenstein Senator Abetz asked: Mr Scott: … I should point out that Mr Loewenstein is not an employee of the ABC. As you pointed out, he has appeared as a guest on our programs, but he is not an employee. Senator ABETZ: But he gets paid a fee from time to time for those appearances? Mr Scott: I would have to check on that. I do not know… Senator ABETZ: It was within the week of that column that the ABC took that decision. Compare Mr Milne's column to Mr Lowenstein's offensive comment, which remained in the ether for five weeks before an apology was finally dragged out of him. Is the ABC willing to continue to have Mr Loewenstein appear as a credible panellist on its programs? Mr Scott: That decision was made, I think, at the editorial level of Insiders. The first I have become aware of this incident was this afternoon. I can take that question on notice, but I understand this was a very offensive statement made— Answer: Antony Loewenstein is a freelance journalist, blogger and author and has appeared as a guest and commentator from time to time on various ABC Radio networks. In 2012 he has appeared on triple j’s Hack and Sunday Night Safran, on Radio National on Common Knowledge, on 702 ABC Sydney Afternoons and on 105.7 ABC Darwin Afternoons. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Michael Francis Hannan Address: Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore 2480 Australia Telephone: 61 2 66203807 (W) Email: [email protected] Citizenship: Australian PRESENT ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT: Professor, School of Arts and Social Sciences, Southern Cross University, Australia I was promoted to this position in 2005 (commencing January 1, 2006) PREVIOUS ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: Tutor in Music (1977-79), Department of Music, The University of Sydney Lecturer in Composition and Writing Techniques (1985-86), Queensland Conservatorium of Music. Senior Lecturer in Music and Head of Music (1986-1989), Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education (Lismore, N.S.W.) Principal Lecturer in Music, and Head of Music (February 1989-November 1989), Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education Associate Professor of Music (1989-93), University of New England, Northern Rivers; and Southern Cross University (1994-2005) QUALIFICATIONS: A.Mus.A. (Piano Performance, AMEB), 1966 NSW Higher School Certificate, 1967 (Level 1 in Mathematics, Level 1 in English, Level 1 in Music, Level 2F in Science, Level 2 in French; Second Place in Music). Bachelor of Arts (Honours II, I) in Music, The University of Sydney, 1972. Ph.D. in Arts (Music), The University of Sydney, 1979. 1 Graduate Diploma of Musical Composition, The University of Sydney, 1982. EDUCATION IN PERFORMANCE, COMPOSITION AND RESEARCH Performance Education: Clarinet student of Douglas Gerke (Newcastle Conservatorium), 1963-66. Organ student of Keith Noake (Newcastle Conservatorium), 1965-66. Piano student of Eileen Keeley (Newcastle Conservatorium), 1966-67. Clarinet player, Newcastle City Orchestra (directed by Errol Russell), 1965-66. Piano and harpsichord student of Dorothy White (Sydney), 1968-69. -

New Fellowship to Honour Peter Sculthorpe

Troy Grant MP Deputy Premier Minister for the Arts MEDIA RELEASE 25 October 2014 NEW FELLOWSHIP TO HONOUR PETER SCULTHORPE A Fellowship will be created to honour the contribution of Peter Sculthorpe AO OBE to Australia’s musical heritage. Deputy Premier and Minister for the Arts, Troy Grant, said the $30,000 Sculthorpe Fellowship will be offered by the NSW Government and the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney every second year beginning in 2015. “Peter Sculthorpe is internationally-renowned and widely acknowledged as Australia’s most significant composer and his passing this year was felt by those who worked with him and enjoyed his music,” Mr Grant said. “The Fellowship will support the professional development of an emerging NSW- based composer or performer dedicated to producing new Australian music. “The NSW Government will fund the Fellowship in line with its commitment to support the professional development of artists across NSW,” Mr Grant said. “The Conservatorium is honoured to continue the legacy of Peter’s composition and support for new Australian music with the announcement of this new Fellowship,” said Dr Karl Kramer, Dean of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. "Peter was a passionate Australian and a renowned teacher whose contribution to the development of Australian music is immense. It is appropriate that this legacy is recognised through the establishment of a new fellowship in his name for an emerging artist. He would have been delighted and honoured,” said Anne Boyd, on behalf of the Peter Sculthorpe Trustees. A committee will be established comprising representatives from the Sculthorpe Trustees, the NSW Government and the University of Sydney to administer the Fellowship. -

ABC Annual Report 1997–1998

Australian Broadcasting Corporation annual report 1997–98 Australian Broadcasting Corporation annual report 1997–98 Australian Broadcasting Corporation annual report 1997–98 contents ABC Corporate Profile charter ABC Charter inside back cover Mission Statement 1 ABC Services 2 The functions and duties which Parliament has given to the ABC are set out in Significant Events 4 the Charter of the Corporation (ss6(1) and (2) of the Australian Broadcasting Priorities – Performance Summary 6 Corporation Act 1983). Financial Summary 10 6(1) The functions of the Corporation are — ABC Board Members 12 (a) to provide within Australia innovative and comprehensive broadcasting services of a ABC Organisation 14 high standard as part of the Australian broadcasting system consisting of national, Executive Members 15 commercial and community sectors and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing, to provide— Statement by Directors 16 (i) broadcasting programs that contribute to a sense of national identity and inform and entertain, and reflect the cultural diversity of, the Australian community; and Review of Operations (ii) broadcasting programs of an educational nature; Regional Services 21 (b) to transmit to countries outside Australia broadcasting programs of news, current Feature: Radio and Television Audiences 25 affairs, entertainment and cultural enrichment that will— National Networks 28 (i) encourage awareness of Australia and an international understanding of Australian News and Current Affairs 39 attitudes on world affairs; and Program Production 42 (ii) enable Australian citizens living or travelling outside Australia to obtain Enterprises 44 information about Australian affairs and Australian attitudes on world affairs; and Symphony Australia 47 (c) to encourage and promote the musical, dramatic and other performing arts in Human Resources 51 Australia. -

Landscape, Spirit and Music: an Australian Story

Landscape, Spirit and Music: an Australian Story ANNE Boyo* (An accompanying compact disc holds the available music examples played. Their place is indicated by boxes in the text.) We belong to the ground It is our power And we must stay close to it Or maybe we will get lost. Narritjin Maymuru Yirrkala, an Australian Aborigine The earth is at the same time mother. She is mother of all that is natural, mother of all that is human. She is the mother of all, for contained in her are the seeds of all. Hildegard of Bingen1 The main language in Australia', David Tacey writes, 'is earth language: walking over the body of the earth, touching nature, feeling its presence and its other life, and attuning ourselves to its sensual reality'.2 If Tacey's view might be taken to embrace all the inhabitants from diverse cultural backgrounds now living in this ancient continent, then the language that connects us is what he calls 'earth language'. Earth language is a meta-language of the spirit which arises as right-brain activity based upon an intuitive connection with our natural environment, the language of place. Earth language has little to do with the left-brain language of human intellectual discourse. It is the territory of the sacred, long known to artists and deeply intuitive creative thinkers from all cultures through all time. It is the territory put off-limits by the * Anne Boyd holds the Chair of Music at the University of Sydney. This professorial lecture was delivered to the Arts Association on 16 May 2002. -

Other Minds 20 Festival of New Music March 6, 7And 8, 2015 SFJAZZ Center 201 Franklin Street (At Fell) San Francisco, CA 94102

For Immediate Release October 2014 Further Info: Blaine Todd Director of Communications (415) 934-8134 ext. 301 office (760) 712-8041 mobile Other Minds 20 Festival of New Music March 6, 7and 8, 2015 SFJAZZ Center 201 Franklin Street (at Fell) San Francisco, CA 94102 Other Minds to Celebrate 20th Anniversary Festival with Unprecedented Retrospective Cast U.S. Premiere of Michael Nyman Symphony No. 2 World Premiere of Pauline Oliveros’ Twins Peeking at Koto Tributes to Australian Composer Peter Sculthorpe and American Maverick Lou Harrison Centennial Commemoration of Armenian Genocide Other Minds (OM) in San Francisco announces its 20th anniversary festival of avant- garde music, taking place in San Francisco on Friday March 6th, 7th and 8th, 2015 at the historically distinguished SFJAZZ Center. This annual event is presented in cooperation with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program. For 20 years Other Minds has searched the world over for the most unconventional and inspiring composers of our time. This March, the Other Minds Festival celebrates its 20th edition, and to mark this occasion, for the first time in its history, will present a retrospective cast from festivals past. Among the many highlights this year are the U.S. premiere of Michael Nyman's Symphony No. 2, featuring the San Francisco School of the Arts Youth Orchestra (SOTA) and accompanied by historical clips from Mexican cinema of the 20th Century; the world-premiere performance of Pauline Oliveros' Twins Peeking at Koto, featuring Oliveros and Norwegian accordion virtuoso Frode Haltli and recent Doris Duke Award recipient Miya Masaoka on koto; Masaoka presents her own world premiere, String Quartet No.