European View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors

THE WORLD BANK GROUP Public Disclosure Authorized 2016 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS Public Disclosure Authorized SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS Public Disclosure Authorized Washington, D.C. October 7-9, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK GROUP Headquarters 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. Phone: (202) 473-1000 Fax: (202) 477-6391 Internet: www.worldbankgroup.org iii INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group (Bank), which consist of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), held jointly with the International Monetary Fund (Fund), took place on October 7, 2016 in Washington, D.C. The Honorable Mauricio Cárdenas, Governor of the Bank and Fund for Colombia, served as the Chairman. In Committee Meetings and the Plenary Session, a joint session with the Board of Governors of the International Monetary Fund, the Board considered and took action on reports and recommendations submitted by the Executive Directors, and on matters raised during the Meeting. These proceedings outline the work of the 70th Annual Meeting and the final decisions taken by the Board of Governors. They record, in alphabetical order by member countries, the texts of statements by Governors and the resolutions and reports adopted by the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group. In addition, the Development Committee discussed the Forward Look – A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030, and the Dynamic Formula – Report to Governors Annual Meetings 2016. -

PROGRAMME What Way Forward for the EU27 and Eurozone?

The Eurofi Financial Forum 2017 organised in association with the Estonian EU Council Presidency TALLINN I 13, 14 & 15 SEPTEMBER PROGRAMME What way forward for the EU27 and Eurozone? LEAD SPONSORS SUPPORT SPONSORS The Eurofi Tallinn Forum mobile website tallinn2017.eurofi.net The Eurofi Financial Forum 2017 Answer polls TALLINN │ 13, 14 & 15 September Post questions during the sessions Check-out the list of speakers and contact attendees Detailed programme and logistics information PROGRAMME TO ACCESS THE TALLINN FORUM MOBILE WEBSITE • Click on the link contained in the SMS you received after registration • Direct access : tallinn2017.eurofi.net • QR code The Eurofi Tallinn Forum mobile website tallinn2017.eurofi.net The Eurofi Financial Forum 2017 Answer polls TALLINN │ 13, 14 & 15 September Post questions during the sessions Check-out the list of speakers and contact attendees Detailed programme and logistics information PROGRAMME DAY 1 I 13 SEPTEMBER AFTERNOON MACRO-ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL CHALLENGES Estonia Room Tallinn Room 12:30 to 13:30 WELCOME LUNCH Foyer 13:30 to 14:00 Opening remarks: Governor A. Hansson Speech: Kara M. Stein p.8 14:00 to 14:30 Exchange of views: C. Clausen, M. Pradhan & D. Wright Outlook for the EU27 economy p.10 14:30 to 15:35 14:30 to 15:35 Sustainable finance: Improving financing prospects for EU EU and emerging market challenges infrastructure projects and mid-sized enterprises p.12 p.14 15:35 to 16:40 15:35 to 16:40 Accelerating the resolution of NPL challenges Challenges raised by green finance and FSB disclosure guidelines p.16 p.18 COFFEE BREAK Foyer 16:55 to 18:00 16:55 to 18:00 Developing Baltic / Eastern European Longevity and ageing: Opportunities capital markets in the context of the CMU and challenges associated with the PEPP p.20 p.22 18:00 to 19:20 The economic, financial stability and trade implications of Brexit p.24 19:20 to 20:15 Exchange of views: C. -

Mr. Petteri Orpo Minister of Finance of Finland Leader of Kokoomus, the National Coalition Party

1(8) FIIA Seminar 18 January 2018: A Comprehensive Reform Package for the EU Mr. Petteri Orpo Minister of Finance of Finland Leader of Kokoomus, the National Coalition Party Your excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, good morning! First of all, I would like to thank you, Mr. Emmanouilidis, and your team for the report Re-energising Europe. It is a great contribution to an important discussion on the future of Europe, to which president Juncker, president Macron and many others, including the still conditional Grand Coalition deal in Germany, have also contributed during the last six months. The report states that European cooperation is not an ideology, but a necessity. Many of us Finns can agree with that statement, since we are here at the far end of Europe. Our economy is very dependent on exports. Isolation is not an option for us. In fact, none of the European countries can flourish on its own. None of us is big enough. We need each other. European Union is far from perfect, but its future direction is up to its member states and citizens. Brexit has forced the remaining EU Member States, the EU27, to think about the vision and mission of the EU after the UK has left. Against all odds, Brexit has pulled us together. Difficulties with Brexit have shown us how bad a choice it is to exit the EU. The future of the UK is unclear; investments and its trade relationships are on hold. 2(8) FIIA Seminar 18 January 2018: A Comprehensive Reform Package for the EU Fortunately, the negotiations took a turn for the better in December. -

Internal Politics and Views on Brexit

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8362, 2 May 2019 The EU27: Internal Politics By Stefano Fella, Vaughne Miller, Nigel Walker and Views on Brexit Contents: 1. Austria 2. Belgium 3. Bulgaria 4. Croatia 5. Cyprus 6. Czech Republic 7. Denmark 8. Estonia 9. Finland 10. France 11. Germany 12. Greece 13. Hungary 14. Ireland 15. Italy 16. Latvia 17. Lithuania 18. Luxembourg 19. Malta 20. Netherlands 21. Poland 22. Portugal 23. Romania 24. Slovakia 25. Slovenia 26. Spain 27. Sweden www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The EU27: Internal Politics and Views on Brexit Contents Summary 6 1. Austria 13 1.1 Key Facts 13 1.2 Background 14 1.3 Current Government and Recent Political Developments 15 1.4 Views on Brexit 17 2. Belgium 25 2.1 Key Facts 25 2.2 Background 25 2.3 Current Government and recent political developments 26 2.4 Views on Brexit 28 3. Bulgaria 32 3.1 Key Facts 32 3.2 Background 32 3.3 Current Government and recent political developments 33 3.4 Views on Brexit 35 4. Croatia 37 4.1 Key Facts 37 4.2 Background 37 4.3 Current Government and recent political developments 38 4.4 Views on Brexit 39 5. Cyprus 42 5.1 Key Facts 42 5.2 Background 42 5.3 Current Government and recent political developments 43 5.4 Views on Brexit 45 6. Czech Republic 49 6.1 Key Facts 49 6.2 Background 49 6.3 Current Government and recent political developments 50 6.4 Views on Brexit 53 7. -

Reuniunea Informală Ecofin

REUNIUNEA INFORMALĂ ECOFIN 5-6 Aprilie 2019 / ŞEFII DELEGAŢIILOR Palatul Parlamentului BUCUREŞTI, ROMÂNIA ROMÂNIA Eugen Orlando Teodorovici Ministrul Finanțelor Publice COMISIA EUROPEANĂ Valdis Dombrovskis Vicepreședinte, Comisar responsabil pentru moneda euro și dialogul social, pentru stabilitatea financiară, serviciile financiare și uniunea piețelor de capital COMISIA EUROPEANĂ Pierre Moscovici Comisar responsabil pentru Afaceri Economice și Financiare, Impozitare și Vamă COMISIA EUROPEANĂ Günther Oettinger Comisar responsabil pentru Buget și Resurse Umane BANCA CENTRALĂ EUROPEANĂ Mario Draghi Președintele Băncii Centrale Europene BANCA EUROPEANĂ DE INVESTIȚII Werner Hoyer Președintele Băncii Europene de Investiții CONSILIUL UNIUNII EUROPENE - SECRETARIATUL GENERAL AL CONSILIULUI Carsten Pillath Director general Afaceri Economice și Competitivitate AUSTRIA Hartwig Löger Ministrul federal de finanțe BELGIA Alexander De Croo Vice Prim Ministru, Ministrul finanțelor și cooperării pentru dezvoltare BULGARIA Vladislav Goranov Ministrul finanțelor CEHIA Alena Schillerová Ministrul finanțelor CIPRU Harris Georgiades Ministrul finanțelor CROAȚIA Stipe Župan Ministru adjunct al Finanțelor DANEMARCA Kristian Jensen Ministrul finanțelor ESTONIA Veiko Tali Secretar General - Ministerul finanțelor FINLANDA Petteri Orpo Ministrul finanțelor FRANȚA Bruno Le Maire Ministrul economiei și finanțelor GERMANIA Olaf Scholz Vice Cancelar, Ministrul federal de finanțe GRECIA Euclid Tsakalotos Ministrul finanțelor IRLANDA Pascal Donohoe Ministrul finanțelor -

EUROGROUP (Inclusive Format) Brussels, 21 January 2019

EUROGROUP (Inclusive format) Brussels, 21 January 2019 PARTICIPANTS President of Eurogroup Mr Mário CENTENO President Belgium: Mr Alexander DE CROO Minister for Finance Bulgaria: Mr Vladislav GORANOV Minister for Finance Czech Republic: Ms Alena SCHILLEROVÁ Minister for Finance Denmark: Mr Kristian JENSEN Minister for Finance Germany: Mr Olaf SCHOLZ Federal Minister for Finance Estonia: Mr Märten ROSS Deputy Secretary-General for Financial Policy and External Relations of Ministry of Finance Ireland: Mr Paschal DONOHOE Minister for Finance and Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform Greece: Mr Efkleidis TSAKALOTOS Minister for Finance Spain: Ms Nadia CALVIÑO SANTAMARÍA Minister for the Economy and Enterprise France: Ms Odile RENAUD-BASSO Director General of the French Treasury Croatia: Mr Zdravko MARIĆ Minister for Finance Italy: Mr Giovanni TRIA Minister of Economy and Finances Cyprus: Mr Harris GEORGIADES Minister for Finance Latvia: Ms Baiba BĀNE State Secretary Lithuania: Mr Vilius ŠAPOKA Minister for Finance Luxembourg: Mr Pierre GRAMEGNA Minister for Finance Hungary: Mr Gábor GION State Secretary Malta: Mr Edward SCICLUNA Minister for Finance Netherlands: Mr Wopke HOEKSTRA Minister for Finance Austria: Mr Harald WAIGLEIN Director General Poland: Ms Teresa CZERWIŃSKA Minister for Finance Portugal: Mr Ricardo MOURINHO FÉLIX State Secretary attached to the Minister for Finance Romania: Mr Eugen Orlando TEODOROVICI Minister of Public Finance Slovenia: Mr Andrej BERTONCELJ Vice Prime Minister and Minister for Finance Slovakia: Mr Peter KAŽIMÍR Minister for Finance Finland: Mr Petteri ORPO Minister for Finance Sweden: Mr Jens GRANLUND Director General, Ministry of Finance Commission: Mr Valdis DOMBROVSKIS Vice President Mr Pierre MOSCOVICI Member Other participants: Mr Mario DRAGHI President of the European Central Bank . -

Social Media in a Crisis Finnish Coin Series Removed by Order of Ministry

EA ON M H IT W N O I T A I C O S S A N I S W E N Y C P N U E B R L I R S U H C E Y D B VOLUME 4 / JUNE 2017 Finnish Coin Series Removed Social Media by Order of Ministry in a Crisis Social media is considered a great way to get as close to the customers as possible. The problem is that not all customers are nice people. The opposite is true. Many a whinger is only happy when he can vent his anger. Raising his voice and attracting attention, he is thus taken more serious than somebody who uses balanced words to express a well- founded opinion. While a private company can decide for itself how to deal with criticism on the internet, mints always have to consider a third party: politics. Although, in theory, the mint operates as an independent The Finnish National Day is 6 December, The initial coin was scheduled to be company, its products are associated with when the entire country celebrates its released on 4 May 2017. The other four the state. And so some politicians become independence. During the 1917 October coins were planned to become available nervous when they feel attacked indirectly Revolution, the Finnish Senate declared between 2017 and 2019. through the mint. This is precisely what happened to its independence from Russia, which The designer was approved by the Soviet Russian Mint of Finland. When it published the In a tender competition, arranged by government a few weeks later. -

Law and Order Do Not Always Go Together. Vigilantism As Citizens Attempt to Enforce Order Outside the Law Is Rising

“Law and order do not always go together. Vigilantism as citizens attempt to enforce order outside the law is rising. Comprehensive studies about the phe- nomenon have been lacking. The 17 case studies and the conceptual and com- parative discussion by the editors go a long way to fill the void. A must read in these times of rising populism and xenophobia.” - Prof. em. Alex P. Schmid, Editor-in-Chief of ‘Perspectives on Terrorism’ and former Officer-in-Charge of the Terrorism Prevention Branch of UNODC. “Theoretically astute, empirically sound, this volume is the authoritative source on the growing phenomena of vigilantism around the world. This study is essential reading for anyone who is interested in understanding the changing nature of coercion, and the shifting relations of social and political order in the 21st century.” - James Sheptycki, York University, Canada. “Vigilantism poses a serious threat to democracy. It is therefore an important, yet understudied phenomenon in criminology. This edited volume raises important issues regarding the conditions under which different kinds of vigilantism emerge. Using case studies from different countries, this edited volume provides challenging new insights which are of importance to both academics and policy makers.” - Prof. Lieven Pauwels, Ghent University, Belgium. “This book is richly researched and extremely timely. The spread of vigilantism in our increasingly fractured world should stimulate debate about the nature and significance of state power, whether ‘private’ vigilante actors are in fact detached from their governments, and when right-wing vigilantism becomes a necessary component of state Fascist operations.” - Prof. Martha K. Huggins, Tulane University (emerita), USA. -

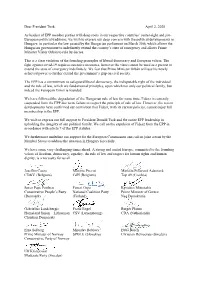

Dear President Tusk, April 2, 2020 As Leaders of EPP Member Parties With

Dear President Tusk, April 2, 2020 As leaders of EPP member parties with deep roots in our respective countries’ center-right and pro- European political traditions, we wish to express our deep concern with the political developments in Hungary, in particular the law passed by the Hungarian parliament on March 30th, which allows the Hungarian government to indefinitely extend the country’s state of emergency and allows Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to rule by decree. This is a clear violation of the founding principles of liberal democracy and European values. The fight against covid-19 requires extensive measures, however the virus cannot be used as a pretext to extend the state of emergency indefinitely. We fear that Prime Minister Orbán will use his newly achieved power to further extend the government’s grip on civil society. The EPP has a commitment to safeguard liberal democracy, the indisputable right of the individual and the rule of law, which are fundamental principles, upon which not only our political family, but indeed the European Union is founded. We have followed the degradation of the Hungarian rule of law for some time. Fidesz is currently suspended from the EPP due to its failure to respect the principle of rule of law. However, the recent developments have confirmed our conviction that Fidesz, with its current policies, cannot enjoy full membership in the EPP. We wish to express our full support to President Donald Tusk and the entire EPP leadership in upholding the integrity of our political family. We call on the expulsion of Fidesz from the EPP in accordance with article 9 of the EPP statutes. -

UNLOCKING the INCLUSIVE GROWTH STORY of the 21ST CENTURY: ACCELERATING CLIMATE ACTION in URGENT TIMES Managing Partner

UNLOCKING THE INCLUSIVE GROWTH STORY OF THE 21ST CENTURY: ACCELERATING CLIMATE ACTION IN URGENT TIMES Managing Partner Partners Evidence. Ideas. Change. New Climate Economy www.newclimateeconomy.report c/o World Resources Institute www.newclimateeconomy.net 10 G St NE Suite 800 Washington, DC 20002, USA +1 (202) 729-7600 August 2018 Cover photo credit: REUTERS/Rupak De Chowdhuri Current page photo credit: Flickr/Neil Palmer/CIAT Photo credit: Chuttersnap/Unsplash The New Climate Economy The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, and its flagship project the New Climate Economy, were set up to help governments, businesses and society make better-informed decisions on how to achieve economic prosperity and development while also addressing climate change. It was commissioned in 2013 by the governments of Colombia, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The Global Commission, comprising, 28 former heads of government and finance ministers, and leaders in the fields of economics, business and finance, operates as an independent body and, while benefiting from the support of the partner governments, has been given full freedom to reach its own conclusions. The Commission has published three major flagship reports: Better Growth, Better Climate: The New Climate Economy Report, in September 2014; Seizing the Global Opportunity: Partnerships for Better Growth and a Better Climate, in July 2015; and The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative: Financing Better Growth and Development, in October 2016. The project has also released a number of country reports on Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, Uganda, and the United States, as well as various working papers on cities, land use, energy, industry, and finance. -

La Fondation Robert Schuman

Having problems in reading this e-mail? Click here Tuesday 10th November 2015 [track] issue 691 The Letter in PDF format The Foundation on and The foundation application available on Appstore and Google Play The "Better Regulation" programme: expertise over politics? Authors: Charles de Marcilly, Matthias Touillon The 2015 version of ""Better Regulation"", the last stage in a policy on- going for the last fifteen years, aims to provide new impetus to European public action, and has been undertaken in view of reforming the Union's decision making process and the ensuing regulations. It intends to improve the efficiency of the European legislative process via greater transparency and the use of pertinent expertise. Read more Elections : Croatia Foundation : Air transport - Prague - Catalonia Financial Crisis : Outlook/Commission - Banks - Greece Migration : Germany - Austria - Spain - Finland - France - Luxembourg Commission : Transport Council : Euro zone - Conclusion/Eurogroup - Conclusion/JAI - Conclusions/Competitiveness Diplomacy : EU/Asia Germany : Volkswagen - G7/Women Bulgaria : Energy France : China/Korea - Syria/Iraq - Defence Portugal : Coalition Romania : Resignation UK : UK/Euro Serbia : Bosnia-Herzegovina Ukraine : Russia/Ukraine Council of Europe : Ukraine - Turkey Eurostat : Energy Eurobarometer : Support/Euro Studies/Reports : Climate - Development - Ireland - UK Culture : Exhibition/Vienna - Exhibition/Zürich - Museum/Paris - Exhibition/London - Exhibition/Stuttgart - Exhibition/Cannes Agenda | Other issues | Contact Elections : Short victory for the opposition in Croatia According to still partial results the right-wing coalition Domoljubna Koalicija (Patriotic Coalition), led by the Democratic Union (HDZ) and Tomislav Karamarko came out ahead in the general elections that took place on 8th November in Croatia. It is due to win 59 of the 151 seats in Parliament. -

ESM Annual Report 2019

2019 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2019 Annual Report Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 Print ISBN 978-92-95085-76-3 ISSN 2314-9493 doi:10.2852/119696 DW-AA-20-001-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-95085-75-6 ISSN 2443-8138 doi:10.2852/768704 DW-AA-20-001-EN-N © European Stability Mechanism, 2020 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Photo credits: © European Stability Mechanism, Steve Eastwood: pages 4, 9 (photo number 2), 15, 17, 18, 21, 25, 26, 31, 33, 35-38, 40, 42-44, 47-49, 53, 60, 63, 66-68 European Stability Mechanism, Blitz Agency: page 9 (photos number 1 and 5) European Union: page 57 Portrait photos: pages 58-59, 61-63 supplied by national Finance Ministries 2019 Annual Report 2 | EUROPEAN STABILITY MECHANISM Letter of Transmittal to the Board of Governors 11 June 2020 Dear Chairperson, I have the honour of presenting to the Board of Governors (BoG) the annual report in respect of the financial year 2019, in accordance with Article 23(2) of the By-Laws of the European Stability Mechanism (By-Laws). The annual report includes a description of the policies and activities of the Euro- pean Stability Mechanism (ESM) during 2019. It also contains the audited financial statements as at 31 December 2019, as drawn up by the Board of Directors (BoD) on 30 March 2020 pursuant to Article 21 of the By-Laws, which are presented in Chapter 4. Furthermore, the report of the external auditor in respect of the financial statements is presented in Chapter 5 and the report of the Board of Auditors (BoA) in respect of the financial statements in Chapter 6.