Issue 3 Crime and Punishment Devolution Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyra Mckee 31 March, 1990 – 18 April, 2019 Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | MAY-JUNE 2019 Lyra McKee 31 March, 1990 – 18 April, 2019 Contents Main feature 16 The writing’s on the wall Exposing a news vacuum News t’s not often that an event shakes our 03 Tributes mark loss of Lyra McKee profession, our union and society as powerfully as the tragic death of Lyra McKee. Widespread NUJ vigils A young, inspirational journalist from 04 Union backs university paper Belfast, lost her life while covering riots Ethics council defends standards Iin the Creggan area of Derry. Lyra became a journalist in the post peace agreement era 05 TUC women’s conference in Northern Ireland and in many ways was a symbol of the Calls for equal and opportunities new Ireland. She campaigned for Northern Ireland’s LGBTQ 07 Honouring Lyra community and used her own coming out story to support Photo spread others. She was a staunch NUJ member and well known in her Belfast branch. “At 29 she had been named as one of 30 European journalists Features under 30 to watch. She gave a prestigious Ted talk two years 10 A battle journalism has to win ago following the Orlando gay nightclub shootings in 2016. She Support for No Stone Unturned pair had signed a two-book deal with Faber with the first book about children and young men who went missing in the Troubles due 12 Only part of the picture out next year. How ministers control media coverage The NUJ has worked with the family to create a fund 22 Collect your royal flush in Lyra’s name and the family said that they have been How collecting societies help freelances inundated with requests to stage events in her name. -

November 2003

Nations and Regions: The Dynamics of Devolution Quarterly Monitoring Programme Scotland Quarterly Report November 2003 The monitoring programme is jointly funded by the ESRC and the Leverhulme Trust Introduction: James Mitchell 1. The Executive: Barry Winetrobe 2. The Parliament: Mark Shephard 3. The Media: Philip Schlesinger 4. Public Attitudes: John Curtice 5. UK intergovernmental relations: Alex Wright 6. Relations with Europe: Alex Wright 7. Relations with Local Government: Neil McGarvey 8. Finance: David Bell 9. Devolution disputes & litigation: Barry Winetrobe 10. Political Parties: James Mitchell 11. Public Policies: Barry Winetrobe ISBN: 1 903903 09 2 Introduction James Mitchell The policy agenda for the last quarter in Scotland was distinct from that south of the border while there was some overlap. Matters such as identity cards and foundation hospitals are figuring prominently north of the border though long-running issues concerned with health and law and order were important. In health, differences exist at policy level but also in terms of rhetoric – with the Health Minister refusing to refer to patients as ‘customers’. This suggests divergence without major disputes in devolutionary politics. An issue which has caused problems across Britain and was of significance this quarter was the provision of accommodation for asylum seekers as well as the education of the children of asylum seekers. Though asylum is a retained matter, the issue has devolutionary dimension as education is a devolved matter. The other significant event was the challenge to John Swinney’s leadership of the Scottish National Party. A relatively unknown party activist challenged Swinney resulting in a drawn-out campaign over the Summer which culminated in a massive victory for Swinney at the SNP’s annual conference. -

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

Scottish Parliament Report

European Committee 3rd Report, 2002 Report on the Inquiry into the Future of Cohesion Policy and Structural Funds post 2006 SP Paper 618 £13.30 Session 1 (2002) Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2002. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax 01603 723000, which is administering the copyright on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. Produced and published in Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body by The Stationery Office Ltd. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office is independent of and separate from the company now trading as The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body publications. European Committee 3rd Report, 2002 Report on the Inquiry into the Future of Cohesion Policy and Structural Funds post 2006 European Committee Remit and membership Remit: 1. The remit of the European Committee is to consider and report on- (a) proposals for European Communities legislation; (b) the implementation of European Communities legislation; and (c) any European Communities or European Union issue. 2. The Committee may refer matters to the Parliamentary Bureau or other committees where it considers it appropriate to do so. 3. The convener of the Committee shall not be the convener of any other committee whose remit is, in the opinion of the Parliamentary Bureau, relevant to that of the Committee. 4. The Parliamentary Bureau shall normally propose a person to be a member of the Committee only if he or she is a member of another committee whose remit is, in the opinion of the Parliamentary Bureau, relevant to that of the Committee. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

The Parish of Edderton During 1940 and World War II. After the Retreat from Dunkirk in June 1940, the British Army and Its Allie

The Parish of Edderton during 1940 and World War II. After the retreat from Dunkirk in June 1940, the British Army and its allies regrouped rapidly to take up defensive positions throughout the United Kingdom. In the North of Scotland the Army High Command was faced with the problem of preventing an effective German landing in the Highlands. Such a landing would have the objectives of isolating the naval bases in the Northern Isles and driving southwards to gain control of the many naval and air force bases around the Moray Firth. The key area in such a strategy was the Dornoch Firth which effectively cuts off Caithness and Sutherland from the rest of Scotland. The crossing of the firth itself was very difficult with its fast tides and shelving mudflats. The road bridge at Bonar and the railway bridge at Culrain were the only ways across that waterway unless the crossing was to be made in the difficult hill country away to the west. If the bridge at Bonar - and to a lesser extent the railway bridge at Invershin - could be held or destroyed, there was then no efficient way by which the tanks and vehicles of an attacking force could drive south out of Sutherland. The Dornoch Firth must have presented the same pattern of problems to the attacking Vikings and the defending Picts twelve hundred years earlier. In July 1940 the Army moved the Norwegian Brigade north to the Tain/Edderton area. They were supported by Royal Engineers and a battalion of the Pioneer Corps. The Engineers set to and prepared sites for demolition charges in both bridges and built concrete pill boxes that would command the approaches to the bridge. -

Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Adopting a Chinese Mantle Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820 Newport, Emma Helen Henke Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820 Emma Helen Henke Newport King’s College London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Research 1 Abstract The thesis examines methods of imagining and appropriating China in Britain in the period 1750 to 1820. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

Maestro Sin Man Ho Escuela WU De Taichi Chuan

REVISTA BIMESTRAL DE ARTES MARCIALES Nº23 año IV MAESTRO SIN MAN HO Escuela WU de Taichi Chuan Origen Histórico de los Katas de Karate Gasshuku & Taikai Nihon Kobudo 2014 Entrevista al maestro José Antonio Cantero Aikido: Entrevista al maestro Ricard Coll Conferencia internacional de Taijiquan en Handan Primer examen oficial de la Federación Japonesa de Iaidô (ZNIR) en España De Taijitsu a Nihon Taijitsu Sumario 4 Noticias 6 Entrevista al maestro Sin Man Ho. Escuela WU de Taichi Chuan [Por Sebastián González] [email protected] 16 Primer examen oficial de la Federación Japonesa de Iaidô (ZNIR) en España www.elbudoka.es [Por José Antonio Martínez-Oliva Puerta] Dirección, redacción, 20 Nace Martial Tribes administración y publicidad: [Por www.martialtribes.com] 22 El sistema Taiji [Por Zi He (Jeff Reid)] Editorial “Alas” 26 De Taijitsu a Nihon Taijitsu C/ Villarroel, 124 [Por Pau-Ramon Planellas] 08011 Barcelona Telf y Fax: 93 453 75 06 Entrevista al maestro José Antonio Cantero [email protected] 32 www.editorial-alas.com [Por Francisco J. Soriano] 38 El ecosistema y la biodiversidad de Capoeira La dirección no se responsabiliza de las opiniones [Por Cristina Martín] de sus colaboradores, ni siquiera las comparte. La publicidad insertada en “El Budoka 2.0” es responsa- 40 VIª Gala Benéfica de Artes Marciales bilidad única y exclusiva de los anunciantes. [Por Andreu Martínez] No se devuelven originales remitidos espontáneamente, ni se mantiene correspondencia 44 Origen Histórico de los Katas de Karate sobre los mismos. [Por Pedro Hidalgo] Director: José Sala Comas 52 Las páginas del DNK: El bastón en el Kenpo Full Defense Jefe de redacción: Jordi Sala F. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday April 22, 2019 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Rock Legends Smart Travels Europe Amy Winehouse - Despite living a tragically short life, Amy had a significant impact on the music Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the industry and is a recognized name around the world. Her unique voice and fusion of styles left a environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. musical legacy that will live long in the memory of everyone her music has touched. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT is a retreat fit for an emperor. CMA Fest Thomas Rhett and Kelsea Ballerini host as more than 20 of your favorite artists perform their 6:30 AM ET / 3:30 AM PT newest hits, including Carrie Underwood, Blake Shelton, Keith Urban, Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, Rock Legends Dierks Bentley, Thomas Rhett, Chris Stapleton, Kelsea Ballerini, Jake Owen, Darius Rucker, Broth- Pearl Jam - Rock Legends Pearl Jam tells the story of one of the world’s biggest bands, featuring ers Osborne, Lauren Alaina and more. insights from music critics and showcasing classic music videos. -

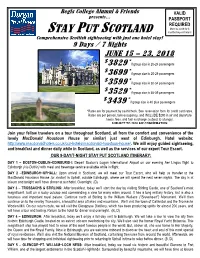

VALID PASSPORT REQUIRED Must Be Valid for 6 Months Beyond Return

VALID PASSPORT REQUIRED Must be valid for 6 months beyond return if group size is 20-24 passengers if group size is 25-29 passengers if group size is 30-34 passengers if group size is 35-39 passengers if group size is 40 plus passengers *Rates are for payment by cash/check. See reservation form for credit card rates. Rates are per person, twin occupancy, and INCLUDE $290 in air and departure taxes, fees, and fuel surcharge (subject to change). SUBJECT TO 2018 AIR CONFIRMATION. Join your fellow travelers on a tour throughout Scotland, all from the comfort and convenience of the lovely MacDonald Houstoun House (or similar) just west of Edinburgh. Hotel website: http://www.macdonaldhotels.co.uk/our-hotels/macdonald-houstoun-house/. We will enjoy guided sightseeing, and breakfast and dinner daily while in Scotland, as well as the services of our expert Tour Escort. OUR 9-DAY/7-NIGHT STAY PUT SCOTLAND ITINERARY: DAY 1 – BOSTON~DUBLIN~EDINBURGH: Depart Boston’s Logan International Airport on our evening Aer Lingus flight to Edinburgh (via Dublin) with meal and beverage service available while in flight. DAY 2 –EDINBURGH~UPHALL: Upon arrival in Scotland, we will meet our Tour Escort, who will help us transfer to the MacDonald Houstoun House (or similar) in Uphall, outside Edinburgh, where we will spend the next seven nights. The day is at leisure and tonight we’ll have dinner at our hotel. Overnight. (D) DAY 3 – TROSSACHS & STIRLING: After breakfast, today we’ll start the day by visiting Stirling Castle, one of Scotland’s most magnificent, built on a rocky outcrop and commanding a view for many miles around.