The People Dimension of Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Heavy Metals in Lakes of Former Tin Mining Sites in the City of Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia

An Analysis of Heavy Metals in Lakes of Former Tin Mining Sites in the City of Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia Mohmadisa Hashim, Wee Fhei Shiang, Zahid Mat Said, Nasir Nayan, Hanifah Mahat & Yazid Saleh To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i2/3977 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i2/3977 Received: 29 Dec 2017, Revised: 03 Feb 2018, Accepted: 10 Feb 2018 Published Online: 13 Feb 2018 In-Text Citation: (Hashim et al., 2018) To Cite this Article: Hashim, M., Shiang, W. F., Said, Z. M., Nayan, N., Mahat, H., & Saleh, Y. (2018). An Analysis of Heavy Metals in Lakes of Former Tin Mining Sites in the City of Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(2), 673–683. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No.2, February 2018, Pg. 673 – 683 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No.2, February 2018, -

EFFECT of LIME on STABILIZATION of MINING WASTE from SABAH, MALAYSIA Baba Bin Musta , Khairul Anuar Bin Kassim , Prasannan Pilla

Malaysian Journal of Civil Engineering 22(2) :202-216 (2010) EFFECT OF LIME ON STABILIZATION OF MINING WASTE FROM SABAH, MALAYSIA Baba bin Musta1, Khairul Anuar bin Kassim2, Prasannan Pillai Rajeev Kumar3* 1School of Science and TechnologyUniversity Malaysia Sabah, 88400, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia 2, 3 Department of Geotechnics & Transportation Faculty of Civil Engineering University Teknologi Malaysia 81310 Skudai, Johor, Malaysia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] _______________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT: This paper deals with the effect of lime on stabilization of mining waste from Sabah, Malaysia. In this study, different percentages of lime as well as fine material were added as additive with the mining waste. The engineering properties were measured by compaction test, unconfined compressive strength tests and permeability tests. The mineral identification and microstructure were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM). The compaction test indicated that the optimum moisture content varied with amount of lime content. The virgin mining waste showed low unconfined compressive strength value due to the very low cementing agent. The samples showed a rapid increase in shear strength when stabilized with lime content ranging from 2 to 8%. The rate of increase in strength is most rapid within two weeks of interaction. This is due to the pozzolanic reaction, which created more rigid - packed structure and small pore space at lime content as low as 2%. More addition of lime had increased the unconfined compressive strength due to the intensive pozzolanic reactions forming more cementitious mineral and created bridge-like structure. However the optimum percentage of lime required was 6% based on the unconfined compressive strength. -

Law in a Plural Society: Malaysian Experience Zaki Azmi

BYU Law Review Volume 2012 | Issue 3 Article 1 9-1-2012 Law in a Plural Society: Malaysian Experience Zaki Azmi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Human Geography Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Zaki Azmi, Law in a Plural Society: Malaysian Experience, 2012 BYU L. Rev. 689 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2012/iss3/1 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 01-AZMI.FIN (DO NOT DELETE) 2/8/2013 2:39 PM Law in a Plural Society: Malaysian Experience Address Given by Former Chief Justice of Malaysia, Zaki Azmi* I. INTRODUCTION This paper concentrates mainly on how Malaysia, a country composed of many races and religions, creates and enforces its laws in order to sustain the peace that has lasted more than half a century. I have recently retired as a judge, so my view on this subject is from a judge’s perspective. Malaysia is located just north of the equator, about halfway around the world from Utah. It is geographically divided into two main regions by the South China Sea. These two regions are the Peninsula Malaysia and Sabah and Sarawak. Peninsula Malaysia was known as Malaya, but in 1963, the British colonies -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Study Tin mining is one of the oldest industries in Malaysia. As what had been researched by James R.Lee (2000), the tin mining started since 1820s in Malaysia after the arrival of Chinese immigrants. The Chinese immigrants settled in Perak and started tin mines. Their leader was the famous Chung Ah Qwee. Their arrival contributed to the needed labour and hence the growth of the tin mining industry. Tin was the major pillars of the Malaysian economy. Tin occurs chiefly as alluvial deposits in the foothills of the Peninsular on the western site. The most important area is the Kinta Valley, which includes the towns of Ipoh, Gopeng, Kampar and Batu Gajah in the state of Perak. But that was long ago before price of tin had fallen greatly and high cost of mining had shutdown the industry. What is left now is the abandoned mine site scattered all over Perak. Some mines are far from populated area and some are in the population itself such as Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP). The campus is located on land that was once an active tin mining site. The residual of past activities can be seen where number of mining ponds can be found scattered in the vicinity of UTP. The main concern from geologist and nature agencies are the identification of Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) and the level of concentration for each element found in the area. Until now, there are only a few numbers of studies in Malaysia that has been done on data collection of PTEs and elevated content of PTEs in former mine. -

The Hannay Family by Col. William Vanderpoel Hannay

THE HANNAY FAMILY BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY AUS-RET LIFE MEMBER CLAN HANNAY SOCIETY AND MEMBER OF THE CLAN COUNCIL FOUNDER AND PAST PRESIDENT OF DUTCH SETTLERS SOCIETY OF ALBANY ALBANY COUNTY HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COPYRIGHT, 1969, BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY PORTIONS OF THIS WORK MAY BE REPRODUCED UPON REQUEST COMPILER OF THE BABCOCK FAMILY THE BURDICK FAMILY THE CRUICKSHANK FAMILY GENEALOGY OF THE HANNAY FAMILY THE JAYCOX FAMILY THE LA PAUGH FAMILY THE VANDERPOEL FAMILY THE VAN SLYCK FAMILY THE VANWIE FAMILY THE WELCH FAMILY THE WILSEY FAMILY THE JUDGE BRINKMAN PAPERS 3 PREFACE This record of the Hannay Family is a continuance and updating of my first book "Genealogy of the Hannay Family" published in 1913 as a youth of 17. It represents an intensive study, interrupted by World Wars I and II and now since my retirement from the Army, it has been full time. In my first book there were three points of dispair, all of which have now been resolved. (I) The name of the vessel in which Andrew Hannay came to America. (2) Locating the de scendants of the first son James and (3) The names of Andrew's forbears. It contained a record of Andrew Hannay and his de scendants, and information on the various branches in Scotland as found in the publications of the "Scottish Records Society", "Whose Who", "Burk's" and other authorities such as could be located in various libraries. Also brief records of several families of the name that we could not at that time identify. Since then there have been published two books on the family. -

The Criminalisation of Bribery in Asia and the Pacific

ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia and the Pacific THE CRIMINALISATION OF BRIBERY IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Proceedings of the 10th Regional Seminar for Asia and the Pacific Held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23-24 September 2010, and hosted by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia and the Pacific THE CRIMINALISATION OF BRIBERY IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Proceedings of the 10th Regional Seminar for Asia and the Pacific Held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23-24 September 2010, and hosted by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Asian Development Bank Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publications of the ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia and the Pacific – The Criminalisation of Bribery in Asia and the Pacific: Frameworks and Practices in 28 Jurisdictions. Paris, ADB/OECD 2010. – Criminalisation of Bribery: Proceedings of the 10th Regional Seminar for Asia and the Pacific. Paris, ADB/OECD 2010. – Strategies for Business, Government and Civil Society to Fight Corruption in Asia and the Pacific. Paris, ADB/OECD, 2009. – Supporting the Fight against Corruption in Asia and the Pacific: ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative Annual Report 2007. Paris, ADB/OECD, 2008. – Fighting Bribery in Public Procurement in Asia and the Pacific. Proceedings of the 7th Regional Technical Seminar. Paris: ADB/OECD, 2008. – Asset Recovery and Mutual Legal Assistance in Asia and the Pacific. Proceedings of the 6th Regional Technical Seminar. Paris: ADB/OECD, 2008. – Managing Conflict of Interest: Frameworks, Tools, and Instruments for Preventing, Detecting, and Managing Conflict of Interest. Proceedings of the 5th Regional Technical Seminar. -

11/29/2016 1

11/29/2016 Elements Chemical Rare Earth Groups symbol Yttrium Y Europium Eu Gadolinium Gd Terbium Tb HYDROMETALLURGY OF Dysprosium Dy XENOTIME AND MONAZITE Holmium Ho Erbium Er PROCESSING Thulium Tm Ytterbium Yb Elements Chemical DR MEOR YUSOFF B. MEOR SULAIMAN, symbol Lutetium Lu MATERIALS TECHNOLOGY GROUP Lanthanum La Heavy Rare Cerium Ce Light Rare Earth Group Praseodymium Pr Earth Group Neodymium Nd Samarium Sm Energy densities of different magnetic materials RE & Malaysian Car Industry Upward & Downward Trend of Light RE Price 1 11/29/2016 REE: Demand and Supply Rare Earth Price (US$/kg) Demand (2016) Supply (2016) Element La 14 35-40,000 tons 75-80,000 tons Ce 15 60-70,000 tons 75-85,000 tons Nd 82 20-30,000 tons 30-35,000 tons Eu 1,800 625-725 tons 450-550 tons Tb 1,400 450-550 tons 300-400 tons Dy 7,500 1500-1800 tons 1300-1600 tons Y 60 12-14 tons 9-11 tons The Rare Earth Chain Rare earth chain : From Mining to Magnet Mining Mineral RE recovery process concentrate from mineral Can be generally categorized into the upstream, midstream and down stream Upstream includes mining and beneficiation steps Upstream Midstream includes cracking and separation and purification of individual RE element Midstream Downstream includes metal making and production of end-product such as magnet, catalyst, etc RE are turned into Separation and Products metal magnet purification of RE Mixed light and heavy RE Downstream 10 Rare Earth Magnet: Value-added from Mineral to High Purity Individual Element Tin Mining in Malaysia Tin mining has been -

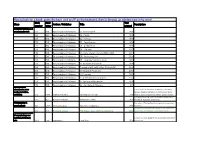

How to Look for a Book

How to look for a book: press the keys cmd and F on the keyboard, then in the pop up window search by word Book Book Year Class Author / Publisher Title Description number letter printed Generalities/General encyclopaedic work 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 01- Environment 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 02 - Plants 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 03 - Animals 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 04 - Early History 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 05 - Architecture 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 06 - The Seas 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 07 - Early Modern History (1800-1940) 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 08 - Performing Arts 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 09 - Languages and Literature 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 10- Religions and Beliefs 2005 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 11-Government and Politics (1940-2006) 2006 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 12- Peoples & Traditions 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 13- Economy 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 14- Crafts and the visual arts 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 15- Sports and Recreation 2008 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 16- The rulers of Malaysia 2011 Documentary-, educational-, news In this book Marina draws attention to the many media, journalism, dangers faced by Malaysia, to concerns to fellow publishing 070 MAR Marina Mahathir Dancing on Thin Ice 2015 citizens, social and political affairs. Double copies. Compilations of he author's thought, reflecting on 070 RUS Rusdi Mustapha Malaysian Graffiti 2012 the World, its people and events. Philosophy & Principles of Tibetan Buddhism applied to everyday psychology 100 LAM HH Dalai Lama The Art of Happiness 1999 problems Introduction and spiritual manual from meditation 100 RIN Rinpoche, Sogyal The Tibetan book of Living and Dying 2002 to the trials and rewards of the spiritual path. -

Tin Mining in Malaysia- Is There Any Revival?

F E AT U R E Tin Mining in Malaysia- Is There any Revival? ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... By: Engr. Yap Keam Min, FIEM, P.Eng. INTRODUCTION Th e r e were two main factors that had contributed to the rapid development of the Malayan tin industry in the mid-19th Ce n t u r y . One was the discovery of rich tin fields in Perak and Selangor. The other was a high demand for tin because of the development of tin canning. By the end of the 19th Century, Malaya was already the world’s largest tin prod u c e r . To d a y, Malaysia only produces less Figure 1: A gravel pump tin mine in Chendriang, than 1.5% of total world pro d u c t i o n Perak in 1989 ( refer to Table 1). Once the brightest star of the Malaysian economy, tin mining is converting agriculture land for mining has now considered a sunset industry. What become too expensive. went wro n g ? The high price of tin has caused great The main reason is because of the total excitement in the tin mining industry. collapse of the world tin industry in People are now talking about investing in October 1985 when the price of tin fell by the industry. The intention of this paper mo r e than 50%. The other factor is there is to give a brief review of the industry has been no new discovery of tin fields. from a former tin miner’s perspective. Pr ev i o u s l y , most of the tin mining land was The future of the tin industry depends on owned by the government. -

MALAYSIA by John C

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF MALAYSIA By John C. Wu1 Malaysia's important mineral resources included antimony, restricted the discharge of waste into the environment that bauxite, clays, coal, copper, gold, ilmenite, iron ore, violate acceptable conditions. It authorized the Ministry of limestone, natural gas, petroleum, rare earths, silica sand, Science, Technology, and the Environment to prescribe and tin. Of these minerals, only its tin reserves were large regulations and orders and to establish standards for and were ranked the world's third largest, after China and protecting the environment from the adverse effects of Brazil. Malaysia, once the world's largest tin producer, economic activities. As of 1994, 15 sets of regulations and ranked sixth in tin mine production, but was the second after orders had been introduced by the Ministry and were China in refined tin production in 1994. Malaysia remained enforced by the Director General of Environmental Quality the world's third largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) producer of the Ministry's Department of Environment. and an important producer of bauxite, copper, crude Under the Environmental Quality Act of 1974, the petroleum, ilmenite, kaolin, monazite, natural gas, and zircon Ministry, in consultation with the Environmental Quality in southeast Asia in 1994. Council, made the Environmental Quality Order 1987 - The mining industry, which contributed about 8% to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for Prescribed Malaysia's gross domestic product (GDP), grew considerably Activities. Under this Order, any project in one of the 19 in 1994, mainly because of increased production of natural prescribed activities was required to conduct an EIA study gas and industrial minerals. -

Download Download

International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology Vol. 29, No. 7, (2020), pp. 2375-2382 Geochemical Evaluation of Contaminated Soil for Stabilisation Using Microbiologically Induced Calcite Precipitation Method [1]Jodin Makinda, [2]Khairul Anuar Kassim, [2]Kamarudin Ahmad, [2]Abubakar Sadiq Muhammed, [2]Muttaqa Uba Zango [1],[2] School of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310, Skudai, Johor Malaysia [1] Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 84000, Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia Abstract Abandoned mines contaminated with heavy metal wastes pose health risk and environmental hazard. Common methods in managing these wastes include pond storage, dry sacking, underground and ocean disposal and phytho-stabilisation but these does not address the associated risks regarding migration of contaminated liquid or when the soil structure is compromised during natural disaster such as earthquake. Due to these limitations, microbiologically induced calcite precipitation method (MICP) is an exciting alternative as it is sustainable and environmentally friendly. This research evaluates mine waste obtained from two sites; Mamut and Lohan Dam, both located at earthquake-prone Ranau Sabah, Malaysia, in term of their physical, mineralogy and morphological characteristics for stabilisation using MICP. Physically, mining wastes from Mamut are of well graded soil with sand (53.9%) and gravel (43.5%), classified as SW (USCS) and A-1-a (AASHTO). Meanwhile, waste from Lohan Dam are of sand (49.9%) and gravel (10.1%), classified as SM (USCS) and A-4 (AASHTO). Constant head test of the soils from the sites showed results of 3.607 x 10-1 and 3.407 x 10-2 cm/s respectively indicate high permeability. -

Responsible Minerals Sourcing for Renewable Energy

Institute for Sustainable Futures Responsible Isf.uts.edu.au minerals sourcing for renewable energy PREPARED FOR: Earthworks © UTS 2019 i About the authors The Institute for Sustainable Futures (ISF) is an interdisciplinary research and consulting organisation at the University of Technology Sydney. ISF has been setting global benchmarks since 1997 in helping governments, organisations, businesses and communities achieve change towards sustainable futures. We utilise a unique combination of skills and perspectives to offer long term sustainable solutions that protect and enhance the environment, human wellbeing and social equity. For further information visit: www.isf.uts.edu.au Research team Citation Elsa Dominish, Sven Teske Please cite as: Dominish, E., Florin, N. and Teske, S., and Nick Florin 2019, Responsible Minerals Sourcing for Renewable Energy. Report prepared for Earthworks by the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable expertise contributed to this research by representatives from industry (including mining, renewable energy, battery storage and recycling), academia and not-for-profit organisations, and the advice from Takuma Watari from the University of Kyoto. The authors would like to thank Yi Ke and Benjamin McLellan for their valuable review. This report was commissioned and funded by Earthworks. Cover photograph: Lithium mine at Salinas Grandes salt desert in Jujuy province, Argentina Executive summary photograph: A creuseur, or digger, descends into a copper and cobalt mine in Kawama, Democratic Republic of Congo (Photo by Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post via Getty Images) Institute for Sustainable Futures University of Technology Sydney PO Box 123 Broadway, NSW, 2007 www.isf.edu.au Disclaimer The authors have used all due care and skill to ensure the material is accurate as at the date of this report, however, UTS and the authors do not accept any responsibility for any losses that may arise by anyone relying upon its contents.