Sourcing Substitution and Related Price Index Biases Alice O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nber Working Paper Series Accounting for Incomplete

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES ACCOUNTING FOR INCOMPLETE PASS-THROUGH Emi Nakamura Dawit Zerom Working Paper 15255 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15255 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2009 We would like to thank Ariel Pakes and Kenneth Rogoff for invaluable advice and encouragement. We are grateful to Dan Ackerberg, Hafedh Bouakez, Ariel Burstein, Ulrich Dorazelski, Tim Erickson, Gita Gopinath, Penny Goldberg, Joseph Harrington, Rebecca Hellerstein, Elhanan Helpman, David Laibson, Ephraim Leibtag, Julie Mortimer, Alice Nakamura, Serena Ng, Roberto Rigobon, Julio Rotemberg, Jón Steinsson, Martin Uribe and seminar participants at various institutions for helpful comments and suggestions. This paper draws heavily on Chapter 2 of Nakamura's Harvard University Ph.D. thesis. This research was funded in part by a collaborative research grant from the US Department of Agriculture and the computational methods in this paper also draw on a working paper by Nakamura and Zerom entitled "Price Rigidity, Price Adjustment and Demand in the Coffee Industry.'' Corresponding author: Emi Nakamura at [email protected]. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by Emi Nakamura and Dawit Zerom. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Emi Nakamura Recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize

Emi Nakamura Recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize EMI NAKAMURA, Associate Professor of Business and Economics at Columbia University, is the recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize. Established in 1998 by the American Economic Association’s (AEA) Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP), the Elaine Bennett Research Prize recognizes and honors outstanding research in any field of economics by a woman not more than seven years beyond her Ph.D. Professor Nakamura will formally accept the Bennett Prize at the CSWEP Business Meeting and Luncheon held during the 2015 AEA Meeting in Boston, MA. The event is scheduled for 12:30-2:15PM on January 3, 2015 at the Sheraton Boston. Emi Nakamura’s distinctive approach tackles important research questions with serious and painstaking data work. Her groundbreaking paper “Five Facts about Prices: A Reevaluation of Menu Cost Models” (Steinsson, Jón and Emi Nakamura. 2008. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123:4, 1415-1464) is based on extensive analysis of individual price data. She finds that, once temporary sales are properly taken into account, prices exhibit a high degree of rigidity consistent with Keynesian theories of business cycles and that prior evidence overstated the degree of price flexibility in the economy. Dr. Nakamura’s work on fiscal stimulus combines a novel cross-section approach to identifying parameters with a careful interpretation of business cycle theory to shed new light on crucial questions in macroeconomics. Her findings imply that government spending can provide a powerful stimulus to the economy at times when monetary policy is unresponsive, e.g. -

Iikbillboard

CANADA (Courtesy The Record) As of 6/13/85 AUSTRALIA (Courtesy Kent Music Report) As of 6/17/85 lir SINGLES 1 5 SINGLESUSSUDIO PHIL COLLINS ATLANTIC /WEA 1 1 WOULD I LIE TO YOU EURYTHMICS RCA 2 1 EVERYBODY WANTS TO RULE THE WORLD TEARS FOR FEARS 2 7 ANGEL MADONNA SIRE VERTIGO/POLYGRAM 3 3 WE ARE THE WORLD USA FOR AFRICA CBS 3 2 DON'T YOU (FORGET ABOUT ME) SIMPLE MINDS VIRGIN / POLYGRAM 4 9 50 YEARS UNCANNY X -MEN MUSHRO OM 4 3 NIGHT DEBARGE GORDY /QUALITY RHYTHM OF THE 5 17 LIVE IT UP MENTAL AS ANYTHING REGULAR 5 6 COLUMBIA /CBS EVERYTHING SHE WANTS WHAM! 6 5 RHYTHM OF THE NIGHT DEBARGE ORDr 6 11 WOULD I RCA - LIE TO YOU EURYTHMICS 7 6 DON'T YOU (FORGET ABOUT ME) SIMPLE MINDS VIRGIN NEW 7 NEVER SURRENDER COREY HART AQUARIUS /CAPITOL 8 4 EVERYBODY WANTS TO RULE THE WORLD TEARS FOR FEARS 8 17 BLACK CARS GINO VANNELLI POLYDOR/POLYGRAM MERCURY 9 12 A VIEW TO A KILL DURAN DURAN CAPITOL 9 8 WE CLOSE OUR EYES GO WEST CHRYSALIS 10 7 WALKING ON SUNSHINE KATRINA & THE WAVES ATTIC /A &M 10 10 19 PAUL HARDCASTLE CHRYSALIS 11 4 CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA SIRE /WEA 11 2 CAN'T FIGHT THIS FEELING REO SPEEDWAGON EPIC 12 8 SMOOTH OPERATOR SADE PORTRAIT /CBS 12 NEW WALKING ON SUNSHINE KATRINA &WAVES CAPITOL 13 15 AXEL F HAROLD FALTERMEYER MCA 13 NEW A VIEW TO A KILL DURAN DURAN EMI 14 13 OBSESSION ANIMOTION MERCURY / POLYGRAM 14 18 WE WILL TOGETHER EUROGLIDERS CBS 15 NEW RASPBERRY BERET PRINCE & THE REVOLUTION PAISLEY PARK /WEA 15 14 WIDE BOY NIK KERSHAW MCA 16 16 HEAVEN BRYAN ADAMS A &M 16 12 NIGHTSHIFT COMMODORES MOTOWN 17 10 TEARS ARE NOT ENOUGH NORTHERN LIGHTS COLUMBIA /CBS 17 13 JUST A GIGOLO DAVID LEE ROTH WARNER 18 14 WE ARE THE WORLD USA FOR AFRICA COLUMBIA /CBS 18 11 THE HEAT IS ON GLENN FREY MCA 19 18 TOKYO ROSE IDLE EYES WEA 19 15 ONE MORE NIGHT PHIL COLLINS WEA Wi's: POWER STATION PARLOPHONE 20 20 THINGS CAN ONLY GET BETTER HOWARD JONES WEA 20 16 SOME LIKE IT HOT %..Copyright 1985, Billboard Publications, Inc. -

New Entry of Record Labels in the Music Industry

Start Me Up: New Entry of Record Labels in the Music Industry Master Thesis MSc Business Administration Management and Entrepreneurship in the Creative Industries Faculty of Economics and Business, Amsterdam Business School Myra Alice Wilhelmina Ruers - 11903929 Supervisor: Dr. M. Piazzai 21st of June 2018 Statement of Originality This document is written by Student Myra Ruers, who declares to take full responsibility for the contents of this document. I declare that the text and the work presented in this document is original and that no sources other than those mentioned in the text and its references have been used in creating it. The Faculty of Economics and Business is responsible solely for the supervision of completion of the work, not for the contents. 2 Abstract The music industry is extremely vibrant, diverse, and inherently uncertain. Record labels are the main intermediaries in this industry, facilitating the connection between the creative input from musicians and the demand from the consumers. Due to many technological advancements, the barriers to entry have decreased significantly, hence making it easier to enter this industry as a new record label. Additionally, strategic integration options allow existing firms to start new ventures by acquiring or initiating subsidiaries. This research focuses on the multiple modes through which new entry can be commenced. These entry modes all have their own characteristics and consequences for the configurations of the industry. The likelihood of entry, the subsequent performance of new record labels, and the effects on the diversity of the output are the main topics that are explored. In this study, databases storing longitudinal information on musical releases are used to compile a dataset with the necessary information on new record labels. -

PAOLO FRESU Discografia Completa

PAOLO FRESU Discografia completa * * * Roberto Ottaviano Aspects Tactus 1983 (Ita) Paolo Damiani/Gianluigi Trovesi Quintet Roccellanea Ismez 1983 (Ita) Paolo Damiani Opus Music ensemble Flash Back Ismez 1983 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet Ostinato Splasc(h) 1985 (Ita) Wheeler/Fresu/Taylor/Oxley/Wistone/Damiani Live in Roccella Jonica Ismez 1985 (Ita) Musica Mu(n)ta Orchestra Anninnia Ismez 1985 (Ita) Piero Marras In Concerto Tekno 1985 (Ita) Giovanni Tommaso Quintet Via G.T. Red Record 1986 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet feat David Liebman Inner Voices Splasc(h) 1986 (Ita) Mimmo Cafiero Emersion Ismj 1986 (Ita) Cosmo Intini Jazz Set See in the Cosmic Splasc(h) 1986 (Ita) Barga jazz Orchestra 1986 Barga jazz 1986 (Ita) Max Nightime Call Solid Air 1986 (Ita) Attilio Zanchi Early Spring Splasc(h) 1987 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet Mamût Splasc(h) 1987 (Ita) Barga jazz Orchestra 1987 Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Mimmo Cafiero I Go Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Paolo Damiani Quintet Pour Memory Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Billy’s Garage Billy’s Garage Jazz Sardegna 1988 (Ita) Aldo Romano Ritual OWL 1988 (Fra) Giovanni Tommaso Quintet To Chet Red Record 1988 (Ita) Paolo Fresu Quintet Qvarto Splasc(h) 1988 (Ita) Roberto Cipelli Moona Moore Splasc(h) 1989 (Ita) Big Bang Orchestra con Phil Woods Embraceable you Philology 1989 (Ita) Tiziano Popoli Lezioni di anatomia Stile libero 1989 (Ita) Paolo Fresu/Furio Di Castri/Francesco Tattara Opale Phrases 1989 (Ita) Paolo Marrocco Grosso modo Stile libero 1989 (Ita) Alice Il sole nella pioggia EMI 1989 (Ita) (#) Artisti vari (Paolo Fresu -

Aggregation in the Presence of Demand and Supply Shocks

Aggregation in the Presence of Demand and Supply Shocks Emi Nakamura £ Harvard University July 11, 2004 Preliminary and Incomplete Comments welcome Abstract This paper points out that the real GDP statisics respond differently to sector- specific demand and supply shocks for the exactly same changes in physical quantities. The paper illustrates how this property arises from the theoretical quantity aggregates that real GDP is designed to approximate. The paper also presents an application to US data suggesting that these factors have contributed significantly to the behavior of US aggregate investment growth in the post-WWII period. Keywords: macroeconomic growth, index number theory. JEL Classifications: C43, O47, E23. £I would like to thank W. Erwin Diewert for extremely helpful and inspiring comments on this paper. I would also like to thank Susanto Basu, Dan Benjamin, N.G. Mankiw, Robert Parker, Marc Prud'homme, Ricardo Reis, Julio Rotemberg, Michael Woodford, Jesse Shapiro, Assaf Ben Shoham, Martin Weitzman, seminar participants at Harvard University and Statistics Canada, and particularly Alice Nakamura and Jon Steinsson for helpful discussions and comments. I would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for financial support. Contact information: Department of Economics, Harvard University, Littauer Center, Cambridge MA 02138. E-mail: [email protected]. Homepage: http://www.harvard.edu/˜ nakamura. 1 1 Introduction At an abstract level, macroeconomists have often interpreted real GDP as a measure of the physical quantity of output. For example, in a classic paper, Robert Solow (1957) notes that aggregate output is denominated in "physical" units. Yet, actual real GDP statistics have certain features that measures of “physical quantity” typically do not. -

Valuation Risk and Asset Pricing∗

Valuation Risk and Asset Pricing∗ Rui Albuquerque, Martin Eichenbaum, Victor Luo, and Sergio Rebelo December 2015 ABSTRACT Standard representative-agent models fail to account for the weak correlation be- tween stock returns and measurable fundamentals, such as consumption and output growth. This failing, which underlies virtually all modern asset-pricing puzzles, arises because these models load all uncertainty onto the supply side of the economy. We propose a simple theory of asset pricing in which demand shocks play a central role. These shocks give rise to valuation risk that allows the model to account for key asset pricing moments, such as the equity premium, the bond term premium, and the weak correlation between stock returns and fundamentals. J.E.L. Classification: G12. Keywords: Equity premium, bond yields, risk premium. ∗We benefited from the comments and suggestions of Fernando Alvarez, Ravi Bansal, Frederico Belo, Jaroslav Borovicka, John Campbell, John Cochrane, Lars Hansen, Anisha Ghosh, Ravi Jaganathan, Tasos Karantounias, Howard Kung, Junghoon Lee, Dmitry Livdan, Jonathan Parker, Alberto Rossi, Costis Skiadas, Ivan Werning, and Amir Yaron. We thank Robert Barro, Emi Nakamura, Jón Steinsson, and José Ursua for sharing their data with us and Benjamin Johannsen for superb research assistance. Albuquerque gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement PCOFUND-GA-2009-246542. A previous version of this paper was presented under the title "Understanding the Equity Premium Puzzle and the Correlation Puzzle," http://tinyurl.com/akfmvxb. The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interest that relate to the research described in this paper. -

LELAND EDWARD FARMER • American, British, and Canadian

LELAND EDWARD FARMER DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA CONTACT INFORMATION DEPARTMENT ADDRESS http://www.lelandfarmer.com Department of Economics [email protected] University of Virginia 248 McCormick Rd Charlottesville, VA 22904-4182 CITIZENSHIP • American, British, and Canadian EMPLOYMENT • Assistant Professor of Economics - Department of Economics, University of Virginia, August 2017 - present EDUCATION • Ph.D. Economics - University of California, San Diego, 2017 Dissertation Title: Discrete Methods for the Estimation of Nonlinear Economic Models Dissertation Committee Co-Chairs: James D. Hamilton, Allan Timmermann • B.S. Mathematical and Computational Science, with Honors - Stanford University Minor in Economics, 2011 RESEARCH FIELDS PRIMARY FIELDS: Macroeconomics, Finance SECONDARY FIELDS: Econometrics, Computational Economics REFEREED PUBLICATIONS • "The Discretization Filter: A Simple Way to Estimate Nonlinear State Space Models." Accepted at Quantitative Economics. • "Discretizing Nonlinear, Non-Gaussian Markov Processes with Exact Conditional Moments," with Alexis Akira Toda, Quantitative Economics, July 2017. WORKING PAPERS • “Pockets of Predictability,” with Lawrence Schmidt and Allan Timmermann. Revision requested at the Journal of Finance. LELAND EDWARD FARMER DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA RESEARCH IN PROGRESS • “Estimating High-Dimensional State Space Models.” • “Learning about the Long Run,” with Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson. • “National Debt and Economic Welfare,” with Roger E. A. Farmer • “The Market Speaks: Inferring the Values of Drugs from Stock Reactions to Changes in the R&D Status,” with Gaurab Aryal, Federico Ciliberto, and Katya Khmelnitskaya. • “What Does the Market Think?,” with Daniel Murphy and Kieran Walsh. SEMINAR AND CONFERENCE PRESENTATIONS • 2020 (including scheduled): Cornell University; Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City; Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; National University of Singapore; Vanderbilt University • 2019: UC Berkeley; University of Warwick; Federal Reserve Bank of St. -

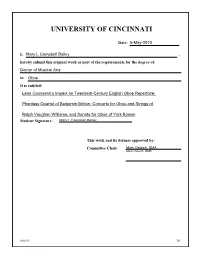

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him. -

Valuation Risk and Asset Pricing

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES VALUATION RISK AND ASSET PRICING Rui Albuquerque Martin S. Eichenbaum Sergio Rebelo Working Paper 18617 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18617 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2012 We benefited from the comments and suggestions of Fernando Alvarez, Frederico Belo, Jaroslav Borovika, Lars Hansen, Anisha Ghosh, Ravi Jaganathan, Tasos Karantounias, Junghoon Lee, Jonathan Parker, Costis Skiadas, and Ivan Werning. We thank Robert Barro, Emi Nakamura, Jón Steinsson, and José Ursua for sharing their data with us and Benjamin Johannsen for superb research assistance. Albuquerque gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement PCOFUND-GA-2009-246542. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. A previous version of this paper was presented under the title “Understanding the Equity Premium Puzzle and the Correlation Puzzle,” http://tinyurl.com/akfmvxb. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w18617.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Rui Albuquerque, Martin S. Eichenbaum, and Sergio Rebelo. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

September / October

CONCERT & DANCE LISTINGS • CD REVIEWS • FREE EVENTS FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 5 Number 5 September-October 2005 THESOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING & OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTS IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers THE TILT OF THE KILT Wicked Tinkers Photo by Chris Keeney BY RON YOUNG inside this issue: he wail of the bagpipes…the twirl of the dancers…the tilt of the kilts—the surge of the FADO: The Soul waves? Then it must be the Seaside Highland Games, which are held right along the coast at of Portugal T Seaside Park in Ventura. Highly regarded for its emphasis on traditional music and dance, this festival is only in its third year but is already one Interview: of the largest Scottish events in the state. Games chief John Lowry and his wife Nellie are the force Liz Carroll behind the rapid success of the Seaside games. Lowry says that the festival was created partly because there was an absence of Scottish events in the region and partly to fill the void that was created when another long-standing festival PLUS: was forced to move from the fall to the spring. With its spacious grounds and variety of activities, the LookAround Seaside festival provides a great opportunity for first-time Highland games visitors who want to experience it all. This How Can I Keep From Talking year’s games will be held on October 7, 8 and 9, with most of the activity taking place on the Saturday and Sunday. -

“For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People”

“For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People” A HISTORY OF CONCESSION DEVELOPMENT IN YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, 1872–1966 By Mary Shivers Culpin National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-CR-2003-01, 2003 Photos courtesy of Yellowstone National Park unless otherwise noted. Cover photos are Haynes postcards courtesy of the author. Suggested citation: Culpin, Mary Shivers. 2003. “For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People”: A History of the Concession Development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872–1966. National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, YCR-CR-2003-01. Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................................iv Preface .................................................................................................................................... vii 1. The Early Years, 1872–1881 .............................................................................................. 1 2. Suspicion, Chaos, and the End of Civilian Rule, 1883–1885 ............................................ 9 3. Gibson and the Yellowstone Park Association, 1886–1891 .............................................33 4. Camping Gains a Foothold, 1892–1899........................................................................... 39 5. Competition Among Concessioners, 1900–1914 ............................................................. 47 6. Changes Sweep the Park, 1915–1918