COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Tympanum Eye (Eardrum) Dorsum Snout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amphibian and Reptile Diversity In

Banisteria, Number 43, pages 79-88 © 2014 Virginia Natural History Society Amphibian and Reptile Communities in Hardwood Forest and Old Field Habitats in the Central Virginia Piedmont Joseph C. Mitchell Mitchell Ecological Research Service, LLC P.O. Box 2520 High Springs, Florida 32655 ABSTRACT A 13-month drift fence study in two replicates of hardwood forest stands and two fields in early succession in the central Virginia Piedmont revealed that amphibian abundance is significantly reduced by removal of forest cover. Pitfall traps captured 12 species of frogs, nine salamanders, four lizards, and five snakes. Twenty-two species of amphibians were captured on the hardwood sites compared to 15 species on the old fields. Eight times as many amphibians were caught per trap day on both hardwood sites than in the combined old field sites. The total number of frogs captured on the hardwoods was higher than in the old fields, as was the total number of salamanders. Numbers of frogs and salamanders captured per trap day were significantly higher in the hardwood sites than in the old field sites. Seven species of small-bodied reptiles were caught in both habitat types. More lizard species were captured in the old fields, whereas more snakes were caught in the hardwoods. The number of individual reptiles captured per trap day was similar in both habitat types. Despite the fact that large portions of the Virginia Piedmont remained in agriculture following losses in the 18th century, reclaimed areas such as in private and state forests, state and national parks, and federal military bases have slowed amphibian declines in some of this landscape. -

Myxozoan and Helminth Parasites of the Dwarf American Toad, Anaxyrus Americanus Charlesmithi (Anura: Bufonidae), from Arkansas and Oklahoma Chris T

51 Myxozoan and Helminth Parasites of the Dwarf American Toad, Anaxyrus americanus charlesmithi (Anura: Bufonidae), from Arkansas and Oklahoma Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Charles R. Bursey Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University-Shenango Campus, Sharon, PA 16146 Matthew B. Connior Health and Natural Sciences, South Arkansas Community College, El Dorado, AR 71730 Stanley E. Trauth Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, State University, AR 72467 Abstract: We examined 69 dwarf American toads, Anaxyrus americanus charlesmithi, from McCurtain County, Oklahoma (n = 37) and Miller, Nevada and Union counties, Arkansas (n = 32) for myxozoan and helminth parasites. The following endoparasites were found: a myxozoan, Cystodiscus sp., a trematode, Clinostomum marginatum, two tapeworms, Cylindrotaenia americana (Oklahoma only) and Distoichometra bufonis, five nematodes, acuariid larvae, Cosmocercoides variabilis, Oswaldocruzia pipiens, larval Physaloptera sp. (Arkansas only), and Rhabdias americanus (Arkansas only), and acanthocephalans (Oklahoma only). We document six new host and four new geographic distribution records for these select parasites.©2014 Oklahoma Academy of Science Introduction (McAllister et al. 2008), Cosmocercoides The dwarf American toad, Anaxyrus variabilis (McAllister and Bursey 2012a) and americanus charlesmithi, is a small anuran tetrathyridia of Mesocestoides sp. (McAllister that ranges from southwestern Indiana and et al. 2014c) from A. a. charlesmithi from southern Illinois south through central Arkansas, and Clinostomum marginatum from Missouri, western Kentucky and Tennessee, dwarf American toads from Oklahoma (Cross and all of Arkansas, to eastern Oklahoma and and Hranitz 2000). In addition, Langford and northeastern Texas (Conant and Collins 1998). Janovy (2013) reported Rhabdias americanus It occurs in various habitats, from suburban from A. -

Cane Toads on Sanibel and Captiva

April 2020 SCCF Member Update Cane Toads on Sanibel and Captiva By Chris Lechowicz, Herpetologist and Wildlife & Habitat Management Director It is that time of year again when it is slowly starting to warm up and any out-of-season rainstorms can trigger Parotoid gland amphibian breeding. On Sanibel, this is limited to frogs and toads as we do not have any salamander species on the island. Besides the southern leopard frog (Lithobates sphenocephalus) which is our sole true winter breeder, the southern toad (Anaxyrus terrrestris) and the giant toad aka cane toad (Rhinella marina) are the usual suspects for late winter/early spring breeding, especially after a heavy rain. The southern toad is native and too often confused for the invasive exotic giant toad — the cane toad — in our area. Giant toads go by several local names, depending on where you are located. In Florida, the most common The first cane toad (Rhinella marina) documented on Sanibel names are cane toad, faux toad, or Bufo toad. Outside right before it was captured while attempting to breed. Female Florida, many people call them marine toads. The local cane toads can lay up to 35,000 eggs at a time (average 8,000 name “Bufo toad” comes from the former scientific name - 25,000). Inset: Cane toad eggs are laid in long strings that (Bufo marinus). In 2008, the cane toad was split off into resemble black beads. These were collected the night they were a new group of South American beaked toads (Rhinella). first documented by SCCF on July 17, 2013. -

Notophthalmus Perstriatus) Version 1.0

Species Status Assessment for the Striped Newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus) Version 1.0 Striped newt eft. Photo credit Ryan Means (used with permission). May 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Jacksonville, Florida 1 Acknowledgements This document was prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s North Florida Field Office with assistance from the Georgia Field Office, and the striped newt Species Status Assessment Team (Sabrina West (USFWS-Region 8), Kaye London (USFWS-Region 4) Christopher Coppola (USFWS-Region 4), and Lourdes Mena (USFWS-Region 4)). Additionally, valuable peer reviews of a draft of this document were provided by Lora Smith (Jones Ecological Research Center) , Dirk Stevenson (Altamaha Consulting), Dr. Eric Hoffman (University of Central Florida), Dr. Susan Walls (USGS), and other partners, including members of the Striped Newt Working Group. We appreciate their comments, which resulted in a more robust status assessment and final report. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Species Status Assessment (SSA) is an in-depth review of the striped newt's (Notophthalmus perstriatus) biology and threats, an evaluation of its biological status, and an assessment of the resources and conditions needed to maintain species viability. We begin the SSA with an understanding of the species’ unique life history, and from that we evaluate the biological requirements of individuals, populations, and species using the principles of population resiliency, species redundancy, and species representation. All three concepts (or analogous ones) apply at both the population and species levels, and are explained that way below for simplicity and clarity as we introduce them. The striped newt is a small salamander that uses ephemeral wetlands and the upland habitat (scrub, mesic flatwoods, and sandhills) that surrounds those wetlands. -

Postbreeding Movements of the Dark Gopher Frog, Rana Sevosa Goin and Netting: Implications for Conservation and Management

Journal o fieryefology, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 336-321, 2001 CopyriJt 2001 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Postbreeding Movements of the Dark Gopher Frog, Rana sevosa Goin and Netting: Implications for Conservation and Management 'Departmmzt of Biological Sciences, Southeastern Louisiana Uniwsity, SLU 10736, Hammod, Louisiamla 70403-0736, USA 4USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, 23332 Highmy 67, Saucier, Mississippi 39574, USA ABSTRACT.-Conservation plans for amphibians often focus on activities at the breeding site, but for species that use temstrial habitats for much of the year, an understanding of nonbreeding habitat use is also essential. We used radio telemetry to study the postbreeding movements of individuals of the only known population of dark gopher frogs, Rana sevosa, during two breeding seasons (1994 and 1996). Move- ments away from the pond were relatively short (< 300 m) and usually occurred within a two-day period after frogs initially exited the breeding pond. However, dispersal distances for some individuals may have been constrained by a recent clearcut on adjacent private property. Final recorded locations for all individ- uals were underground retreats associated with stump holes, root mounds of fallen trees, or mammal bur- rows in surrounding upland areas. When implementing a conservation plan for Rana sevosa and other amphibians with similar habitat utilization patterns, we recommend that a temstrial buffer zone of pro- tection include the aquatic breeding site and adjacent nonbreeding season habitat. When the habitat is fragmented, the buffer zone should include additional habitat to lessen edge effects and provide connec- tivity between critical habitats. -

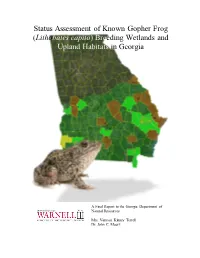

Status Assessment of Known Gopher Frog (Lithobates Capito) Breeding Wetlands and Upland Habitats in Georgia

Status Assessment of Known Gopher Frog (Lithobates capito) Breeding Wetlands and Upland Habitats in Georgia A Final Report to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Mrs. Vanessa Kinney Terrell Dr. John C. Maerz Final Performance Report State: Georgia Grant No.: Grant Title: Statewide Imperiled Species Grant Duration: 2 years Start Date: July 15, 2013 End Date: July 31, 2015 Period Covering Report: Final Report Project Costs: Federal: State: Total: $4,500 Study/Project Title: Status assessment of known Gopher Frog (Lithobates capito) breeding wetlands and upland habitats in Georgia. GPRA Goals: N/A ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------------- *Deviations: Several of the Gopher frog sites that are not located in the site clusters of Ft. Stewart, Ft. Benning, and Ichauway are located on private property. We have visited a subset of these private sites from public roads to obtain GPS coordinates and to visually see the condition of the pond and upland. However, we have not obtained access to dip net these historic sites. Acknowledgements This status assessment relied heavily on the generous collaboration of John Jensen (GA DNR), Lora Smith (Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center), Anna McKee (USGS), Beth Schlimm (Orianne Society), Dirk Stevenson (Orianne Society), and Roy King (Ft. Stewart). William Booker and Emily Jolly assisted with ground-truthing of field sites. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared By: John C Maerz and Vanessa C. K. Terrell Date: 3/1/2016 Study/Project Objective: The objective of this project was to update the known status of Gopher frogs (Lithobates capito) in Georgia by coalescing data on known extant populations from state experts and evaluating wetland and upland habitat conditions at historic and extant localities to determine whether the sites are suitable for sustaining Gopher frog populations. -

AMPHIBIANS Please Remember That All Plants and Animals Nature Lover’S Paradise

Please help us protect our Hampton, VA Natural Resources Welcome to Hampton’s City Parks. The City of Hampton is located in what is Hampton City Park’s called the Peninsula area of the Coastal Plain region of the State of Virginia. The forests, fields, rivers, marshes, and grasslands are a AMPHIBIANS Please remember that all plants and animals nature lover’s paradise. found in Hampton’s City Parks are protect- During your visit to any of Hampton’s out- ed by law. It is illegal to molest, injure, or standing city parks, we hope you have the opportunity to observe our many and diverse remove any wildlife including their nests, species of fauna and flora. eggs, or young. It is also illegal to remove, cut, damage, or destroy any plants (including plant parts) found in the park. Help us conserve YOUR natural resources. Green Frog "Enjoy Hampton's Natural Areas" Chorus Frog Tadpole For more information… If you have any questions regarding this brochure, or if you would like more information about Hamp- ton City Parks and Recreation parks please contact us at: Hampton Parks , Recreation & Leisure Services 22 Lincoln Street Hampton, VA 23669 Tel: 757-727-6348 www.hampton.gov/parks American Bullfrog Frogs and Toads Salamanders What is an Amphibian? The typical frog (genus Rana) has a relatively While salamanders look similar to lizards, they are smooth skin and long legs for leaping. While very different. The typical salamander (many gene- Amphibians belong to the Class Amphibia. The the typical toad (genus Bufo) has a warty skin ra) has smooth or warty moist skin (not scaly) and is word “amphibious” is based on Greek words and and short legs for jumping. -

Amphibian Annual Report

amphibian survival alliance Annual Report FY2018 saving amphibians together © Robin Moore www.amphibians.org 1 The Amphibian Survival Alliance would like to give special to thanks the following organizations and individuals: This report and the work of ASA is dedicated to the memory of Dr. George B. Rabb (1930–2017). www.amphibians.org 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 A Message from the Amphibian Survival Alliance 5 Introduction 6 News from the ASA Partnership 8 Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group Detroit Zoological Society Defenders of Wildlife Endangered Wildlife Trust Global Wildlife Conservation Rainforest Trust Reptile, Amphibian and Fish Conservation the Netherlands Synchronicity Earth Zoological Society of London News from the ASA Secretariat 25 General Amphibian Diseases and Disease Mitigation Key Biodiversity Areas Communications News from ASA Advisors 31 Amphibian Ark IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group Annual expenditure 34 Donor acknowledgment 37 Global Council 39 ASA Secretariat 40 ASA Partners 41 www.amphibians.org 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations Amphibian Ark AArk Amphibian Red List Authority ARLA Amphibian Specialist Group ASG Amphibian Survival Alliance ASA Amphibian Survival Alliance Global Council ASA GC Conservation Planning Specialist Group CPSG Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust Durrell European Association of Zoos and Aquaria EAZA Endangered Wildlife Trust EWT Global Wildlife Conservation GWC Key Biodiversity Areas KBA Madagascar Flora and Fauna MFG Rainforest Trust -

Got a Question?

News for the kids to learn about the bay? ou ready Are y of Tampa Bay! Got a Question? Winter 2017/18 Ask a Scientist! I saw a turtle in my backyard near a hole in the ground; In This Issue: • Learn about the Gopher do I need to bring him to the water? Tortoise • Meet and Greet: Friends of the Gopher Tortoise Not necessarily, it sounds like • Conservation Corner it may have been a gopher • Fun Facts tortoise! Not all turtles belong • Fun Activity: Key“stone” in the water. They should be Species Painted Rocks left in the environment in which they were originally found. Though they are all considered “turtles,” there are actually Mark your Calendars! three general types: turtles, terrapins, and tortoises. Most turtles spend most of their time in the water. They have modified feet with webbing or flippers and a flat shell to move easily through the water. There are both freshwater turtles, like your common yellow-bellied slider (Trachemys scripta), and 7 feet deep. They not only provide and sea turtles, like your leatherback protection for the tortoise, but also provide (Dermochelys coriacea). Terrapins are given a home for over 350 types of animals their name because of where they can be and insects. A few of these animals are found. The term terrapin is given to types the burrowing owl, indigo snake, gopher of turtles that usually spend their time in frog, pine snake, rabbits, Florida mouse, GREAT AMERICAN brackish water, the mixture of fresh and gopher cricket and many more. Gopher CLEANUP saltwater, like the ornate diamondback tortoises are labeled a keystone species Saturday, March 17 terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin macrospilota). -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Amphibian Taxon Advisory Group Regional Collection Plan

1 Table of Contents ATAG Definition and Scope ......................................................................................................... 4 Mission Statement ........................................................................................................................... 4 Addressing the Amphibian Crisis at a Global Level ....................................................................... 5 Metamorphosis of the ATAG Regional Collection Plan ................................................................. 6 Taxa Within ATAG Purview ........................................................................................................ 6 Priority Species and Regions ........................................................................................................... 7 Priority Conservations Activities..................................................................................................... 8 Institutional Capacity of AZA Communities .............................................................................. 8 Space Needed for Amphibians ........................................................................................................ 9 Species Selection Criteria ............................................................................................................ 13 The Global Prioritization Process .................................................................................................. 13 Selection Tool: Amphibian Ark’s Prioritization Tool for Ex situ Conservation .......................... -

“Bufo” Toad (Rhinella Marina) in Florida1 A

WEC387 The Cane or “Bufo” Toad (Rhinella marina) in Florida1 A. Wilson and S. A. Johnson2 The cane toad (Rhinella marina), sometimes referred to high for many native Australian animals that attempt to as the “bufo,” giant, or marine toad, is native to extreme eat cane toads (e.g., monitor lizards, freshwater crocodiles, southern Texas through Central and tropical South and numerous species of snakes), and numbers of native America, but is established in Florida. Cane toads were predators have plummeted in areas where the toxic toads initially introduced to Florida as a method of biological pest have invaded. Cane toads continue to expand westward control in the 1930s. The toads were supposed to eat beetles across the Top End of Australia into the Kimberly region threatening the sugar cane crop, but the introduced popula- and southward toward Sydney. tion did not survive. In the 1950s, a pet importer released about 100 cane toads (maybe on accident or on purpose, no one is sure) at the Miami airport, and there are other docu- mented incidents of purposeful releases in south Florida. Cane toads have since spread through much of south and central Florida. As of 2017, they were established in much of the southern peninsula as far north as Tampa (Figure 1), and there have been several isolated sightings in northern Florida and one in southeast Georgia. A small population appears to be established in Deland in Volusia County, and there was a population that survived for several years near Panama City. Cane toads are still available through the pet trade, and isolated sightings in northern Florida may be escaped or released pets.