Elementary Teachers Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Carr – Bibliography]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1319/carr-bibliography-401319.webp)

[Carr – Bibliography]

Bibliography Steven C. McNeil, with contributions by Lynn Brockington Abell, Walter, “Some Canadian Moderns,” Magazine of Art 30, no. 7 (July 1937): 422–27. Abell, Walter, “New Books on Art Reviewed by the Editors, Klee Wyck by Emily Carr,” Maritime Art 2, no. 4 (Apr.–May 1942): 137. Abell, Walter, “Canadian Aspirations in Painting,” Culture 33, no. 2 (June 1942): 172–82. Abell, Walter, “East Is West – Thoughts on the Unity and Meaning of Contemporary Art,” Canadian Art 11, no. 2 (Winter 1954): 44–51, 73. Ackerman, Marianne, “Unexpurgated Emily,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), 16 Aug. 2003. Adams, James, “Emily Carr Painting Is Sold for $240,000,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), 28 Nov. 2003. Adams, John, “…but Near Carr’s House Is Easy Street,” Islander, supplement to the Times- Colonist (Victoria), 7 June 1992. Adams, John, “Emily Walked Familiar Routes,” Islander, supplement to the Times-Colonist (Victoria), 26 Oct. 1993. Adams, John, “Visions of Sugar Plums,” Times-Colonist (Victoria), 10 Dec. 1995. Adams, Sharon, “Memories of Emily, an Embittered Artist,” Edmonton Journal, 27 July 1973. Adams, Timothy Dow, “‘Painting Above Paint’: Telling Li(v)es in Emily Carr’s Literary Self- Portraits,” Journal of Canadian Studies 27, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 37–48. Adeney, Jeanne, “The Galleries in January,” Canadian Bookman 10, no. 1 (Jan. 1928): 5–7. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Oil Paintings from the Emily Carr Trust Collection (ex. cat.). Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1958. Art Gallery of Ontario, Emily Carr: Selected Works from the Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery (ex. cat.). Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1974. -

A Review Essay

The enigma of emily carr A Review Essay LESLIE DAWN Unsettling Encounters: First Nations Imagery in the Art of Emily Carr Gerta Moray Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006. 400 pp. Illus. $75.00 cloth. Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon Charles C. Hill, Johanne Lamoureux, and Ian M. Thom (Vancouver: Douglas & MacIntyre, with the National Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2006). 336 pp. Illus. $75.00 cloth. o Canadian artist has gen- struction of personal and na tional Nerated, or produced, more textual identities and the place of Aboriginal material than Emily Carr. That this peoples and cultures within them. is still true is evident from the two The exhibition catalogue contains books on the artist that appeared in eight essays by ten contributors from the summer of 2006. The National various disciplines, arranged more Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver or less chronologically. Ethnologists Art Gallery produced Emily Carr: Peter Macnair and Jay Stewart open New Perspectives on a Canadian by reinvestigating Carr’s 1907 tourist Icon, the catalogue for the latest excursion to Alaska, during which Carr retro spective. Concurrently, she formed the project for painting a UBC Press pub lished Gerta Moray’s documentary record of the poles of the long awaited monograph Unsettling Aboriginal villages of the Canadian Encounters: First Nations Imagery Northwest Coast. Contributing to the in the Art of Emily Carr. The two discussion on the veracity of Carr’s complementary studies combine the later autobiographical writings, they formats of lavishly illustrated coffee compare her published recollections table books with scholarly writings with archival records and the remaining that attempt defini tive statements on fragments of Carr’s missing Alaska this protean artist. -

Canadian, Impressionist & Modern

CanAdiAn, impressionist & modern Art Sale Wednesday, december 2, 2020 · 4 pm pt | 7 pm et i Canadian, impressionist & modern art auCtion Wednesday, December 2, 2020 Heffel’s Digital Saleroom Post-War & Contemporary Art 2 PM Vancouver | 5 PM Toronto / Montreal Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art 4 PM Vancouver | 7 PM Toronto / Montreal previews By appointment Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Friday, October 30 through Wednesday, November 4, 11 am to 6 pm PT Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Monday, November 16 through Saturday, November 21, 11 am to 6 pm ET Heffel Gallery, Toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue Together with our Yorkville exhibition galleries Thursday, November 26 through Tuesday, December 1, 11 am to 6 pm ET Wednesday, December 2, 10 am to 3 pm ET Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein referred to as “Heffel” Consignments or “Auction House” [email protected] appraisals CONTACt [email protected] Toll Free 1-888-818-6505 [email protected], www.heffel.com absentee, telephone & online bidding [email protected] toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 shipping Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 [email protected] ottawa subsCriptions 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 [email protected] Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-6505 montreal Catalogue subsCriptions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 beneficial to the art collector. An Annual Subscription entitles vanCouver you to receive our Auction Catalogues and Auction Result Sheets. 2247 Granville Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6H 3G1 Our Annual Subscription Form can be found on page 103 of this Telephone 604-732-6505, Fax 604-732-4245 catalogue. -

Activating Emily

Activating Emily The Emily Carr P AP Activity Book HE T D A O L N W O D Free! This book has a life of its own! Colour and draw in it, “activate” it with your tablet or phone, and take it on a field trip! Tell your friends about it! Use your device to take photos of your work throughout this book, and share them on Instagram and Twitter with the hashtag #ActivatingEmily. The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria is located on the traditional territories of the Lekwungen peoples, today known as the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations. We are grateful for the opportunity to live and learn on this territory. Looking at Emily Carr p. 3 With the Whole Body For the Love of Nature p. 8 Emily’s Colours p. 10 The New Canadian p. 14 Field Trips! p. 17 Look for these corners! In conjunction with this book, the Activating Emily companion app provides an interactive experience with Emily Carr’s art. Look for artworks and images framed by corners like these. Download the app to your tablet or mobile device, open it, and follow the on-screen instructions to scan these pieces. There you’ll find additional videos, stories and more! Get the Activating Emily app for FREE on your iOS device now from the iTunes App Store, or visit the Gallery welcome desk to sign out a device to use. In some low-light areas of the Gallery the pieces might be more difficult to scan. Try shifting your angle of view or repositioning yourself for more light and better results. -

NATIONAL GALLERY of CANADA and the VANCOUVER ART GALLERY

Exhibition Reviews 157 Exhibition Reviews Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon . NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA and the VANCOUVER ART GALLERY. Mounted at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. 2 June–4 September 2006. Accompanying publication: Charles Hill, Johanne Lamoureux, and Ian M. Thom. Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon. Toronto: Douglas McIntyre, 2006. 335 p. ISBN 1-55365-173-1. Another exhibition about Emily Carr could not be unpopular , could it? Everyone, even schoolchildren, has at least heard of Emily Carr . As a child, I first noticed her when snooping through my father ’s art books, where I found Emily Carr, Her Paintings and Sketches, the exhibition catalogue for the 1945 memorial show put on after her death by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario. The odd cover image of fantastic totem creatures near bundled Native women made me look inside, and there I saw massive plasticine structures in the forms of buildings, trees, and columns. That moment of discovery bubbled up again when I entered the 2006 show , organ- ized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver Art Gallery. My anticipation grew, knowing that Emily Carr ’s paintings were waiting silently beyond the first doorway, simmering with their intensity and grandeur. The concept of this show was a key element of the Vancouver Art Gallery’s seventy-fifth anniversary plans, since the Emily Carr collection is an important part of the Gallery’ s holdings. What was planned was a fresh look at the artist that involved revisiting the major twentieth-century exhibitions that had formerly presented her work, an honest presentation that would rely on new sources and perhaps dispel or at least deflate myths or assumptions about the artist. -

Helen Kemp Frye's Writings On

Helen Kemp Frye’s Writings on Art Helen Kemp Frye’s Writings on Art Compiled and Edited by Robert D. Denham Helen Kemp Frye’s Writings on Art Compiled and Edited by Robert D. Denham This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Robert D. Denham All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3659-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3659-3 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................... vii 1. “The University and the Fine Arts” (1933) ............................................. 1 2. “Loan Collections from the Art Gallery of Toronto” (1936) ................... 7 3. “Children in the Gallery” (1937) ........................................................... 11 4. “The Permanent Collection” (1937) ...................................................... 17 5. “Children at the Art Gallery of Toronto” (1937) ................................... 25 6. “Yvonne Williams” (1938) .................................................................... 29 7. “Yvonne McKague Housser” (1938) ..................................................... 33 8. “Fritz Brandtner” -

Elements & Principles of Design

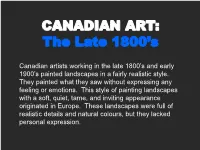

CANADIAN ART: The Late 1800’s Canadian artists working in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s painted landscapes in a fairly realistic style. They painted what they saw without expressing any feeling or emotions. This style of painting landscapes with a soft, quiet, tame, and inviting appearance originated in Europe. These landscapes were full of realistic details and natural colours, but they lacked personal expression. Homer Watson John A. Fraser September Afternoon, Eastern At the Rogers Pass, Summit of the Townships 1873 Selkirk Range, B.C. 1886 CANADIAN ART: THE GROUP OF SEVEN The Group of Seven was founded in 1920 to develop a new style of Canadian painting with a distinct Canadian identity. These artists painted what they saw, but added imagination and feeling. They were especially interested in expressing the wild, untamed spirit of the Canadian wilderness in their paintings. The artists often travelled into the wilderness to make sketches in the open air. They wanted to capture the atmosphere, the effects of light, and the spirituality and ruggedness of the northern Canadian landscape. In order to accomplish this, their style was also rugged, expressive, and powerful. THE GROUP OF SEVEN PAINTING STYLE a)Colours: bold and vibrant or bold and dark/dull high contrast between lights and darks b) Shapes/Forms: simplified with few details almost 2 dimensional abstract c) Brushstrokes: thick paint application (impasto) often visible (not blended) Franklin Carmichael Lake Wabagishik 1928 Mirror Lake 1929 Arthur Lismer A September Gale, Georgian Bay 1921 Bright Land 1938 J.E.H. MacDonald The Solemn Land 1921 Mist Fantasy 1922 F.H. -

Seeing and Not Seeing: Landscape Art As a Historical Source

ch08.qxd 2/5/08 1:41 PM Page 140 Seeing and Not Seeing: Landscape Art as a Historical Source COLIN M. COATES Colin Coates is the Canada Research Chair in Cultural Landscapes at Glendon College, York University. During the years that I taught Canadian Studies courses at the University of Edinburgh, I some- times asked my British students to complete the phrase, “As Canadian as ...”The answers they gave were usually fairly predictable: “maple syrup,” “snow,” “a Mountie.” If I had to answer the question myself, I would probably finish the sentence with “landscape.” After all, as the second- largest country in the world, Canada has a lot of landscape. More importantly, the image Canadians project to themselves and others is often of rural or “wilderness” landscapes, even if they rarely visit them, and the human population of the country is crowded into the cities and towns that hug the American border. But the images of Canada iconic to Canadians and tourists alike are usually (apparently) pristine forests, lakes, mountains, and icebergs, not the cities, high-rises, and highways that more accurately define the day-to-day life of the vast majority of Canadians today. Canadians are not unique in finding the essence of their country outside their urban settings. Many countries locate their self-image in the countryside or the wilderness: Scotland, for instance, markets its majestic lochs and craggy islands, even if most Scots live in the tamer cities and suburbs near the English border. In the Canadian case, landscapes are often refracted through particular aesthetic approaches. -

FROM EMILY CARR to JOY COGHILL . . . and BACK: Writing the Self in Song of This Place

FROM EMILY CARR TO JOY COGHILL . AND BACK: Writing the Self in Song of This Place SHERRILL GRACE "I hate painting portraits. I am embarrassed at what seems to me to be impertinence and presumption, pulling into visibility what every soul has [a] right to keep private. The better a portrait, the more indecent and naked the sitter must feel." (Journal 31 December 1940, Hundreds and Thousands•, Carr 891-92) I Y THE TIME BRITISH COLUMBIA painter Emily Carr (1871-1945) expressed these sharp reservations about portraiture in one of Bher autobiographical texts, she had begun to achieve some of the recognition that, since her death, has marked her as one of the finest talents of her generation, a painter, as Sharyn Udall has demonstrated, easily on a par with Frieda Kahlo and Georgia O'Keefe, and an artist Canadians now rank with (or even above) the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. For all her formidable personality and artistic daring (see Figure 1), Carr was a reserved, private person, and her comment (above) on portraiture suggests that she may have feared how others would depict her when she was no longer alive to protest. That she wrote her own autobiography in several books and stories suggests, moreover, that she wanted to control the invention of her life, to tell it herself, as she saw it, rather than trust to others to get things right. And well might she have been concerned about portraiture because few other Canadian artists have attracted as much attention from biographers and other artists as has Carr. -

Students Learn About Emily Carr's

Different Ways of Looking Objective: Students learn about Emily Carr’s landscape paintings. Description of Activity: Students participate in a drawing exercise, approaching the same landscape from multiple viewpoints, using Emily Carr as a model. Duration: 1 session, 60 minutes Background Information for Teachers: Emily Carr was born in 1871 to British parents who had settled in Victoria. She described herself as a child who preferred to play in the barn rather than the nursery. Her love of nature remained an integral part of her life and influenced the course of her work as an artist, not only in her subject, but also in her enthusiasm for sketching outdoors. Carr’s desire to depict the landscape of British Columbia reflects the idea that first-hand observation is crucial to creating an authentic image, a conviction shared by many artists. She did her work at a time when Canadian artists such as the Group of Seven began using nature as a symbol for national identity. Although she was not tied closely to the Group of Seven, many authors argue that Carr’s forest scenes evoke a sense of what it means to be Canadian. There are many different ways to interpret Carr’s work: her paintings may convey an environmental message, a spiritual meaning or a sense of isolation. Preparation for Teachers: • Examine Forest, British Columbia, 1931–32, Old and New Forest, 1931–1932, and Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky, 1935. See Appendix A for reproductions. Consider how Carr changes her perspective on the same subject matter. • Read the excerpt from Hundreds and Thousands (Appendix B) that follows this activity, detailing Carr’s love of the forest. -

Canadian, Impressionist & Modern

CanAdiAn, impressionist & modern Art Sale Wednesday, May 30, 2018 · 7 PM · toronto Canadian, impressionist & modern art auCtion Wednesday, May 30, 2018 4 PM Post-War & Contemporary Art 7 PM Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art Design Exchange The Historic Trading Floor (2nd floor) 234 Bay Street, Toronto Located within TD Centre previews Heffel Gallery, Calgary 888 4th Ave SW, Unit 609 Friday, April 13 through Saturday, April 14, 10 am to 6 pm Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Saturday, May 5 through Tuesday, May 8, 11 am to 6 pm Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Thursday, May 17 through Saturday, May 19, 11 am to 6 pm Design Exchange, Toronto The Exhibition Hall (3rd floor), 234 Bay Street Located within TD Centre Saturday, May 26 through Tuesday, May 29, 10 am to 6 pm Wednesday, May 30, 10 am to noon Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein refered to as “Heffel” Fine Canadian art or “Auction House” [email protected] toronto appraisals 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 [email protected] Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 E–mail: [email protected], Internet: www.heffel.com absentee and telephone bidding [email protected] ottawa 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 shipping Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-8884 [email protected] montreal subsCriptions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 [email protected] Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 vanCouver Catalogue subsCriptions 2247 Granville Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6H 3G1 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 604-732-6505, Fax 604-732-4245 beneficial to the art collector. -

Undergraduate Program VIEWBOOK

Undergraduate Program VIEWBOOK E C U Undergraduate Program VIEWBOOK 2019 / 20 Emily Carr University of Art + Design Undergraduate Program VIEWBOOK 2019 / 20 Emily Carr University of Art + Design Welcome. Shape the future of art and design. Foundation year, you map an individual We are a community of creators, artists, path by selecting one of 11 exciting makers, and innovators. We follow our majors toward your Bachelor of Design, creativity and express our ideas through Bachelor of Fine Arts or Bachelor of an infinite variety of artistic forms. Media Arts degree. Through practice-based learning, in Live, work and play where the mountains small classes and among a diverse and touch the sea. Vancouver is renowned talented community, you will explore and for its natural beauty and cultural experiment. Our undergraduate programs diversity, and is home to a thriving offer opportunities to collaborate and economy of creative industries, studios connect through interdisciplinary, and start-ups. hands-on work with your fellow students and award-winning faculty. You will study and create in our world-class campus, a space designed First year Foundation launches your for learning, developing and realizing journey. Our Foundation program is the your potential. first year of all our undergraduate degrees. Foundation year provides the Join us. core skills to equip you with new technical perspectives, vital relationships cover: ADRIELE AU, BFA Visual Arts and critical insights with which to make Double Puddluv, 2019 (detail) personal degree choices. Following the crepe paper, wood, mixed media Make. NATALIE PAN + SABRINA LAM, BDes Communication Design Protential, 2019 public awareness campaign + multimedia tools Undergraduate Program VIEWBOOK 2019 / 20 Emily Carr University of Art + Design Our Programs.